I became a God at the age of seventeen. I developed powers beyond my wildest dreams and turned desires into foolproof actualities.

What I mean is that, after my parents divorced, I was free to do as I pleased and so I spent every school evening building a new home in my father’s office. This world was founded upon a number of utopian ideals (no violence, no pain, no hatred, just harmony – harmony!), which were quickly abandoned when my first humans needed food and happiness, both of which required money. With no time to dream, I got down to work and learned the weight of responsibility. I fretted over mowing the lawn and paying the bills and making sure food was on the table. Not only did my adult Sims need me to design their home and care for it, they also needed me to show them the toilet or point them to their bed if I didn’t want the evening to end in tragedy. Denying myself such basic needs, I was eventually unable to cope with the stress of endless clicking and my failed ambitions. I would cry with my avatars and consider starting all over. Whenever I did, the world resisted my founding ideals again.

It just wouldn’t work. Life was not meant to exist without friction. And, I realized a few months ago as I stood on the shore of Lake Zurich, I was never meant to be a God in full control of my surroundings. But just how many nights had I spent trying to do exactly this? And was it because I wanted control in an uncontrollable world? Or because I wanted to build communities where none existed before? All these thoughts came back to me as water slapped the dock behind Zurich’s Rote Fabrik during my brief pause from Nikima Jagudajev’s six-hour long performance Basically, held at Shedhalle on 23 April 2022. Perhaps these recollections ebbed forth because the setting resembled the place I grew up: South Lake Tahoe, like Zurich, is situated on a large alpine lake with mountains framing the horizon.

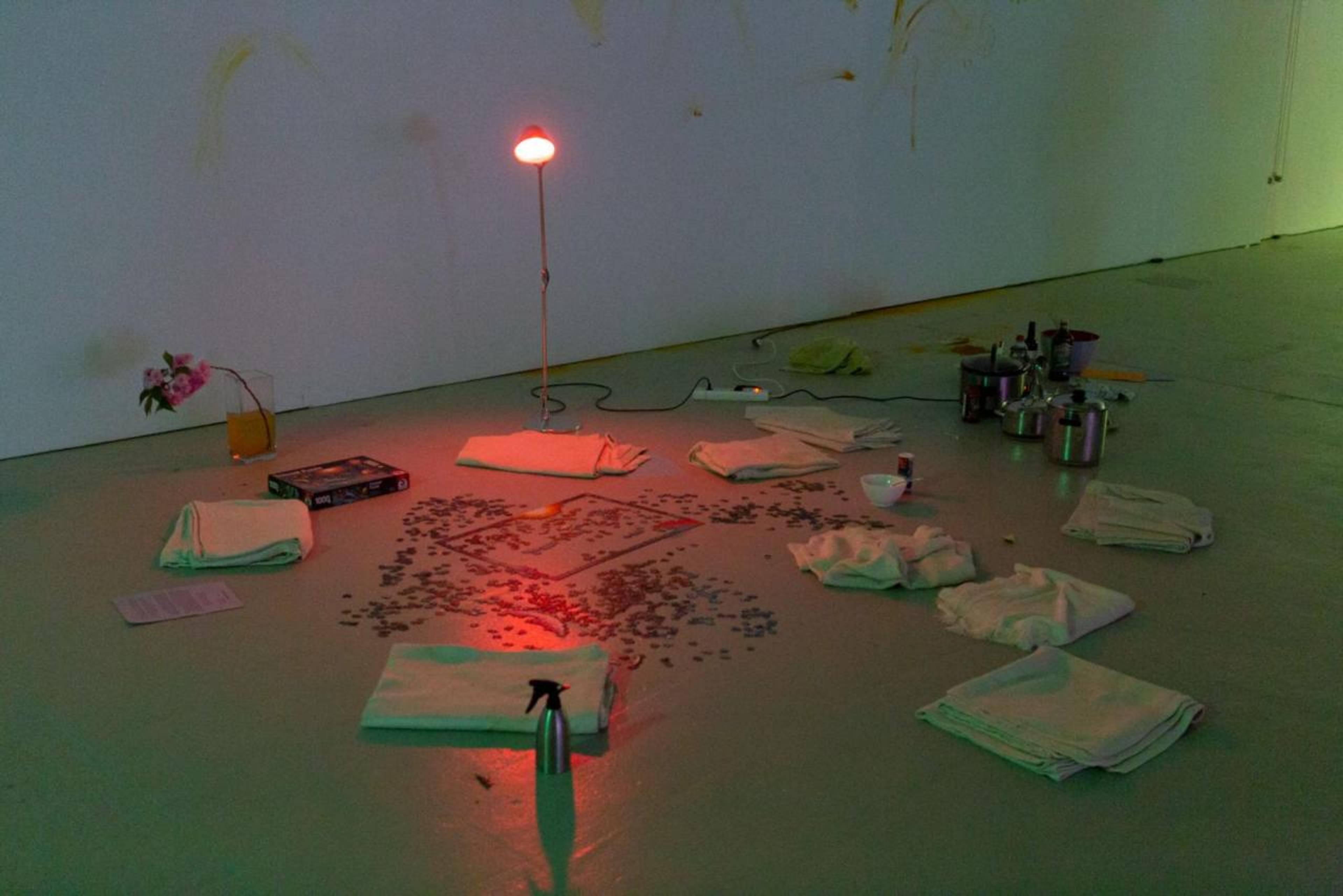

Or perhaps it was the décor of Jagudajev’s piece that reminded me of the early furnishings of my Sims empire. Inside the Shedhalle, Jagudajev had turned the exhibition space into a large living room. A TV that looped rippling light on water sat in the far-left corner, and house plants on wheels were sprinkled throughout the space. In the back right corner were cushions, books, and a puzzle the audience was welcome to work on. Nearby was a bean bag, a computer, and a video camera prepared for live I Ching castings. Bathed in the soft evening light emanating from the skylights, this cozy corner made me feel like an intruder. Whoever had been here before the performance had forgotten their iPhone near the computer (iMessages constantly popped up) and they had left open a copy of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents (1998). It felt indecent to read the passage that was open, but I did, and I had a hard time deciphering its relevance; like much else in Basically while I first witnessed it. When I put the flat of my hand on the bean bag, it was still warm.

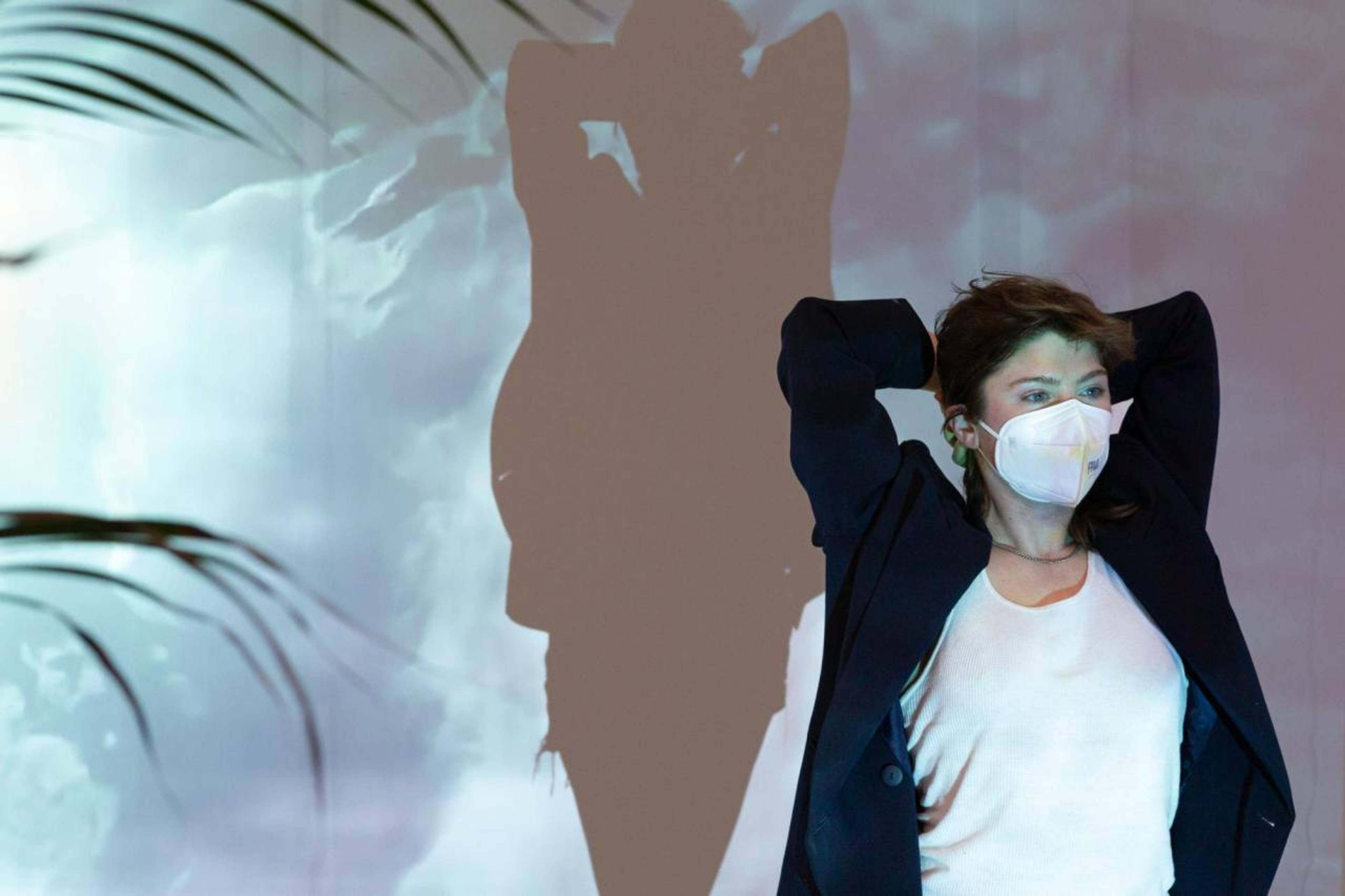

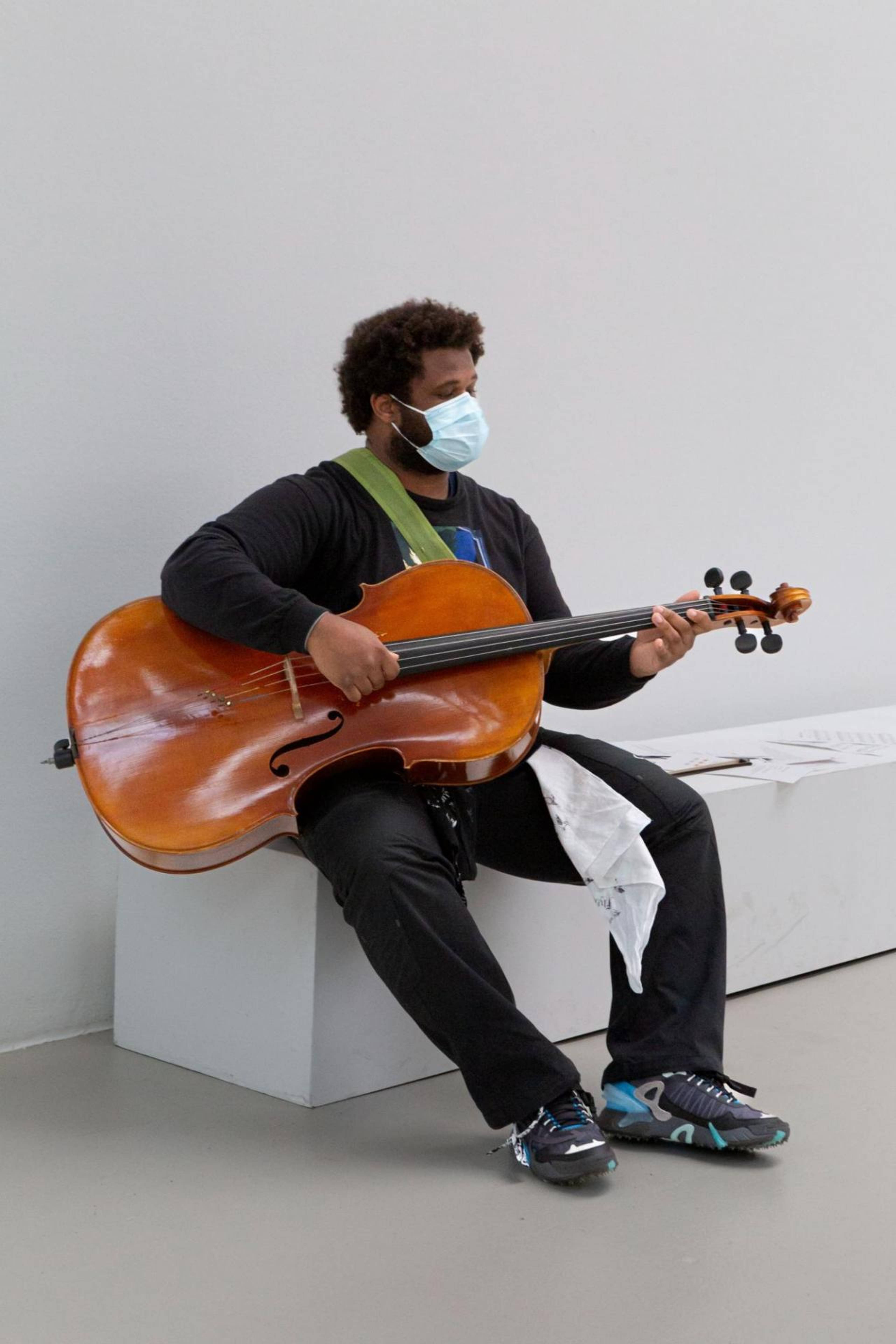

Nikima Jagudajev, Basically, 2022. Performance views, “Protozone 6: Are you coming?” Shedhalle, Zurich

The room was also equipped with two turntables and a rotation of DJs who played anything from Suicide, Liquid Liquid, 80s funk, and The Cramps to contemporary classical co-composed by Jagudajev, Jordan Balaber, and Lester St. Louis, which was in the vein of Morton Feldman’s subdued gestures in constant modulation. For hours and hours, the sound drifted from quiet to loud and even louder when two guitarists burst into a twenty-minute rendition of “Krampus,” another piece that Jagudajev co-composed with Balaber and St. Louis. In the press release, the three of them describe how “Krampus” plays with temporal distortion, which could just as easily describe Basically at large. Inside the Shedhalle, time shrunk and expanded as the dancers got lost in slow sequences of arm movements above their heads, lulling me into a trance — a trance that snapped when the dancers wiped real or imaginary sweat from their brows then trotted off to some other part of the scenery.

Like The Sims, Jagudajev’s Basically was slightly sinister due to the air of unpredictability. Oscillating between stagnation and disruption, the group of performers would spend long stretches of time chatting and lounging around, oblivious to the viewers, before bursting into synchronized actions without warning. These movements included flashy dances from a non-existent Vegas show, meditative moves drawing on Qi Gong, and other sensual and intimate choreographies that themselves could turn menacing: the aforementioned single arm raised above the head gestures might emerge from a sequence of self-caressing, and just when it seemed like the dance was suggesting lovemaking, the dancers would make a fist, extend their fore- and middle finger, then insert them into their mouths. Were they putting a gun into their mouths or just inducing vomit with two fingers? Then it looked like they were smoking a cigarette.

Nikima Jagudajev, Basically, 2022. Performance views, “Protozone 6: Are you coming?” Shedhalle, Zurich

With their seemingly random configurations and durations, the dances remained hermetic even though the space they were creating was open and inviting. Over time, the synchronous movements that were closed off to logics of progression created a space of heightened perceptiveness in me. Around hour three, I began to grasp the slight variations of the same gestures in different dances and how the one dance could slide into the next, suggesting a great sense of fluidity between the individual choreographies. One dance that may have seemed violent could also be associated with the more meditative piece, and this, in turn, could become sensual. These felt like opposites being conflated until I glanced again at the television screen, with its video of rippling light on water. Opposing forces in surprisingly natural interplay.

Jagudajev told me that friction is necessary and that homogeneity “is the death of us.” Drawing on feminist thinkers like Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, and Anna Tsing, they are interested in an entanglement where the sum is greater than its parts (which messes with the possibility of individual realities) and where divergent beings “contaminate” one another with contesting forms and deviant forces. “Contamination is how we transform,” they told me, “since we have to interface with the fact that nothing is static; we need bacteria, we need viruses, our bodies are not closed.” Instead, we are to understand ourselves as a part of a larger, ever-changing ecosystem — and one that isn’t always harmonious. We become what we are through difference. But for difference to be productive in our process of becoming, we need to have the space to explore.

For the choreographer, this means relinquishing the claim to authority. By letting go and embracing the unknown, Jagudajev created a welcoming space in Basically where performers and visitors could also do as they pleased. Two teenagers, for instance, worked on the puzzle in the corner for nearly an hour, while other visitors flipped through the books, chatted with their friends, or ate the sweet potato curry that was available halfway through the performance. The food is another important element of their work and one that they’ve utilized in other performances. It’s a bridge connecting two modes of being in the space, doing or watching, through a shared moment of nourishment.

Nikima Jagudajev, Basically, 2022. Installation view, “Protozone 6: Are you coming?” Shedhalle, Zurich

Nikima Jagudajev, Basically, 2022. Performance view, “Protozone 6: Are you coming?” Shedhalle, Zurich

At the time, I didn’t dare eat the curry (it seemed to spicy for my delicate stomach), so I stepped outside to the docks and had my quiet thoughts about The Sims. But now I wonder whether I was too shy to cross the bridge and become some other. Or perhaps – and this is what I actually believe – Jagudajev wishes to trouble the boundary between viewers and performers, to dismantle it, while also making us aware of its existence. You are a part of Basically by eating – and yet, you the viewer and they the performers remain, undeniably, not the same. It’s just that we’re in some new configuration together.

Part of Jagudajev’s stated goal is to create a space where marginalized people can be together “without dominating power structures dictating the exchange.” The androgynous youths and non-binary beauties that made up the cast of Basically ignored the codes of theatricality, like the so-called fourth wall, and instead erected a wall of autonomy. They were not simply pretending we were not there while representing some scene; they were frankly uninterested in whether anyone was there at all. I was struck by their freedom and spontaneity – such as when some of the performers started making finger paintings on the walls with turmeric – as well as by their investment in caring for one another. As they ate curry together, whispered in each other’s ears, or went for strolls like two lovers oblivious to the world, it felt like the only thing that mattered to them was the work they were doing. Jagudajev characterizes that work as an “open-ended act of being together” to create a new space, a new way of living. Understanding this aim puts an entirely different spin on the work that sometimes felt hermetically sealed off and not unlike watching avatars move in a world separate from one’s own. It suggests that the performance is only a small glimpse into a much larger project with certain (utopian) ideals.

After stepping outside of the Shedhalle and watching the waves as thoughts about The Sims came back to me, I did another tour around the room and threw glances at the locked-in performers. I lounged wherever I wanted, studied the score for “Orbit Arps,” the other musical piece co-composed for Basically, which lay on the bench behind the turntables, then examined the piles of turmeric next to the hazardous sachets for home Covid-19 tests scattered about. I even inserted a couple of pieces into the puzzle. And towards the end of the evening, I thought about how I had played The Sims wrong all along. What’s needed in the games you play is acceptance of difference, of elements that can never be controlled. Life never looks like it’s supposed to. To be a God, Jagudajev teaches, you have to be focused even as you learn to let go. And if you do, you can build communities where none had existed before.

___

Basically

as part of “You’re So Busy”

Shedhalle, Zurich

19–25 July 2022