Such is the rapid churn of Generative AI that anything worth writing about one day is rendered obsolete the next. This places the cultural critic in a peculiar position, adopting both the role of an anthropologist tracing events in real time, and of an historian who, given the ongoing acceleration of technological forces, might as well be decoding cave paintings. As artist, writer, and filmmaker Hito Steyerl predicted, her new essay collection, Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat (2025), became a “time capsule for future historians” upon its publication, or a warning of the zombification impending from statistical conformism. Tracing “the swift proliferation of machine learning-based technologies and their impact on society, art and different types of labour,” Medium Hot predicts the magnitude of slop across our feeds, as well as the warfare, labor extraction, and surveillance marketing associated with data-based cultures. These technologies create a reality warp that, in turn, impacts the way we see ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

Günseli Yalcinkaya: Throughout your new book, the presence of magical thinking seems unavoidable, whether it’s the torrent of PR mythologies that surround AI, from tech and media institutions, or the vibe of the technologies themselves. This seems to reflect a wider moment of re-enchantment – was this intentional?

Hito Steyerl: I think I called it re-enchatment instead of re-enchantment, because its agents are chatbots. Machine learning works by correlation, by analogy, in a way more like alchemy than cause-and-effect-based science. So, in that sense, there is a proximity between magical thinking and elements of machine learning. But this magical vibe is blatantly pushed by large corporations just to flog their products; they’re not magical at all, but rather enshittifying.

GY: It reminds me of that Marshall McLuhan quote, “Mysticism is just tomorrow’s science dreamed today.” But what’s interesting to me is that, for the most part, we could explain how these technologies work if we wanted to, yet we choose to remain mystified. Why do you think that is?

HS: With machine learning, something happens around what we used to call instrumental rationality – a rationality deployed for profit and domination. What we’re seeing now is some kind of instrumental irrationality, one that can be operationalized for profit and domination. Irrationality is not new, of course. But automated irrationality? What do you think?

Hito Steyerl, Medium Hot: Images in The Age of Heat, 2025. Courtesy: Verso Books

GY: Ultimately, everyone has incentives and motivations that aid in the narrativizing of certain belief systems over others. I’ve been seeing this a lot with quantum science, for instance, with corporations propagating disinformation about the multiverse or teleportation. Is it really that different from a TikTok grifter trying to sell quantum oil? I mean, what all of these examples have in common is capital, but it all seems very Renaissance.

HS: Alchemy was this sort of junction, where it could be both magic and science. In the Renaissance, they separate, and magic is left behind. Whereas in our times, the one left behind is probably science, if we look at all the attacks against universities.

GY: Speaking of alchemy, did you see that scientists at CERN [the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Geneva] managed to turn lead into gold?

HS: But in very small quantities and very unstably, like existing for microseconds. It’s like micro-dosing gold. [both laugh]

GY: One of your essays touches on how artistic uses of AI distract from the technology’s military implications and its role in rising fascism. Do you think there’s any redeeming side to artists engaging with Gen AI?

HS: Artists have successfully used toilets before, so why not large language models? The question is just, in this industrial constellation, is it possible to sort of turn AI against its own military-industrial logic, or rather its ML-industrial logic? We are early on and things are moving very fast, so the answer depends on your timeframe. Now? If it is a critical engagement that goes against the hype, arms race and techno-authoritarianism. But in ten years? God knows what will have happened by then.

If we’re missing a cooperative human infrastructure, tech in itself cannot solve the problem. That’s always been wishful thinking.

GY: If most modern technologies have origins in the military-industrial complex, is it really possible to use these technologies without implicating ourselves?

HS: A big topic that wasn’t so present when I completed my book is techno-fascism, and the roles played by both analytic and generative AI therein. Today, Palantir is creating deportation databases with data siphoned off by DOGE agents. Fascist slop from the White House’s social media accounts celebrates the elimination of Palestinians. AIgorithmized disinformation facilitates declarations of emergency rule. Is it possible to avoid implication? To some degree, by either starting a different stack, or by just leaving this space. But it is very hard for anyone to completely avoid it. Even buying a solar panel means implication. What’s more, the different infrastructures that do exist are inconvenient, lack reach, and do not provide addictive sloptainment. But, as prototypes, these do exist.

GY: What sorts of infrastructures?

HS: The Fediverse, data commons, public models, DIY and open-source tech, solarpunk, all that stuff. But the base for all that would really be a different attitude towards political organization. If we’re missing a cooperative human infrastructure, tech in itself cannot solve the problem. That’s always been wishful thinking.

GY: I really like something you write, that as AI becomes more homogenous, the world around it becomes more chaotic. How has this evolved since you first reflected on that statement?

HS: I first put it in a film in 2019, one made purely by algorithms from an early general adversarial network, except for a single documentary scene, of a fascist march in Germany. As Nazis yell “Foreigners out,” a voiceover goes: “The more AI tries to predict everything, the more things get out of control.” In 2019, this just was an intuition, but the relation between rising fascism and AI has become manifest since.

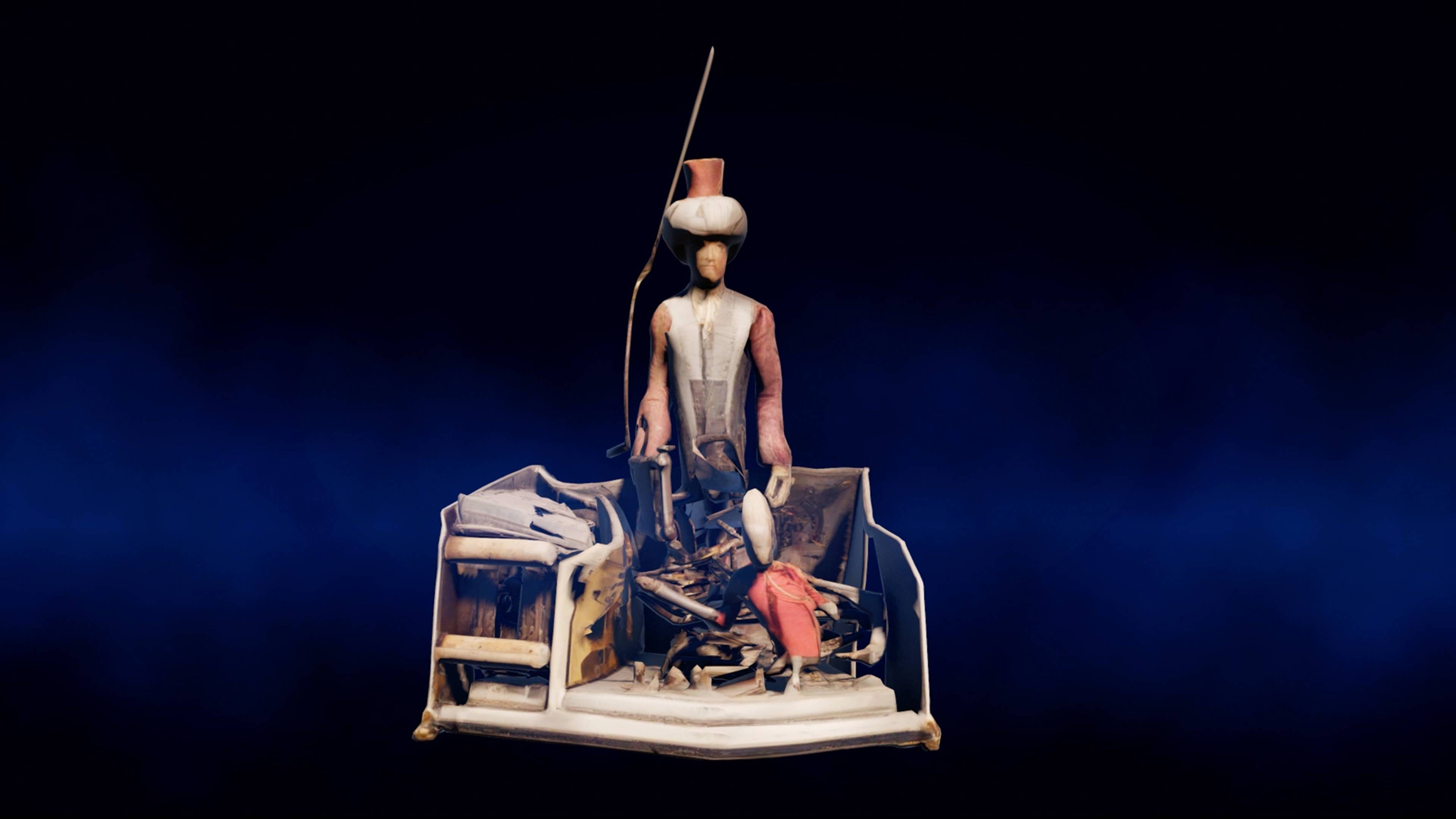

Views of Hito Steyerl, “Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other,” MAK, Vienna, 2025

Both: © kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

GY: Nowadays, with our identities embedded within these neural networks, there’s a statistical distribution of the self. How do you think this is changing the way we perceive ourselves and the world around us? Do we speak a machine language to machines trained on human data?

HS: It looks like a mutual training process, but really, automated systems are training humans to interact in a way that’s useful for them. In a way, humans are trained to become Veo prompt people – you know, like the Google Veo 3 memes, of generated stock-footage people speculating about their origins and dismissing the conspiracy theory that they originate from prompts. Most evenings, I think: Who prompted all this shit?

All of these systems, these models, are also closed into themselves. I mean, this is a multiverse happening already. Each LLM has its own event horizon; like in Agar.io, for example, these bubbles try to swallow one another until there is only one left. It’s kind of funny, because the idea of capitalism was to have a free market, which means competition.

GY: Is there a way to participate in these systems while retaining some digital sovereignty?

HS: The thing is that, even if you try to reduce your data footprint, you wind up correlated from your peers’ data. Nevertheless, basic security protocols do exist. We are just starting to collect resources and tutorials for that at carrier-bag.net, a platform I run with artist Francis Hunger at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich. Just one example: Is it really a good idea to tell OpenAI about your mental health? Are you really sure you want to do that?

The Anthropocene might turn out to be quite a short period in history, though, because humans are working so hard on superseding themselves, by leaving control to systems like capitalism or AI.

GY: What initially excited me about AI, before its widespread deployment for surveillance and warfare or similar, was its pseudo-magical qualities, the ways the systems connect threads of data that are very different to how humans think, and therefore could help us see outside of our Anthropocenic bubble. I think that’s why I’m also falling down the rabbit hole of quantum theory, because it presents an alternative reality – one that is, ironically, more accurate than the current Newtonian model.

HS: For me, quantum science is much more inspiring than the discourse around AI, because at the end of the day, the latter is all about optimization and statistics. It smells of bureaucracy and of ledgers and endless tables with insurance data. So, it’s a bit dusty in the end, a lot of forms.

But quantum immediately draws you into much vaster and more expansive questions about reality, entanglement, the nature of the universe, and so on. It’s a very different horizon. The Anthropocene might turn out to be quite a short period in history, though, because humans are working so hard on superseding themselves, by leaving control to systems like capitalism or AI.

GY: This was the reason for my own disenchantment – it all feels very Promethean.

HS: That’s how machine learning technology is being optimized for now, right? I’m not sure whether it really could have been pushed somewhere else, but I think no one even tried.

GY: What do you make of the symmetry between techno-authoritarian AI and techno-feudalist network states?

HS: I think the predecessor of the network state is the duty-free zone, the special economic zone. These have existed for a long time, also within nation states, to optimize conditions for capital.

GY: You also write about how Gaza and Ukraine have become testing grounds for AI warfare. How do you think AI is changing weapons development?

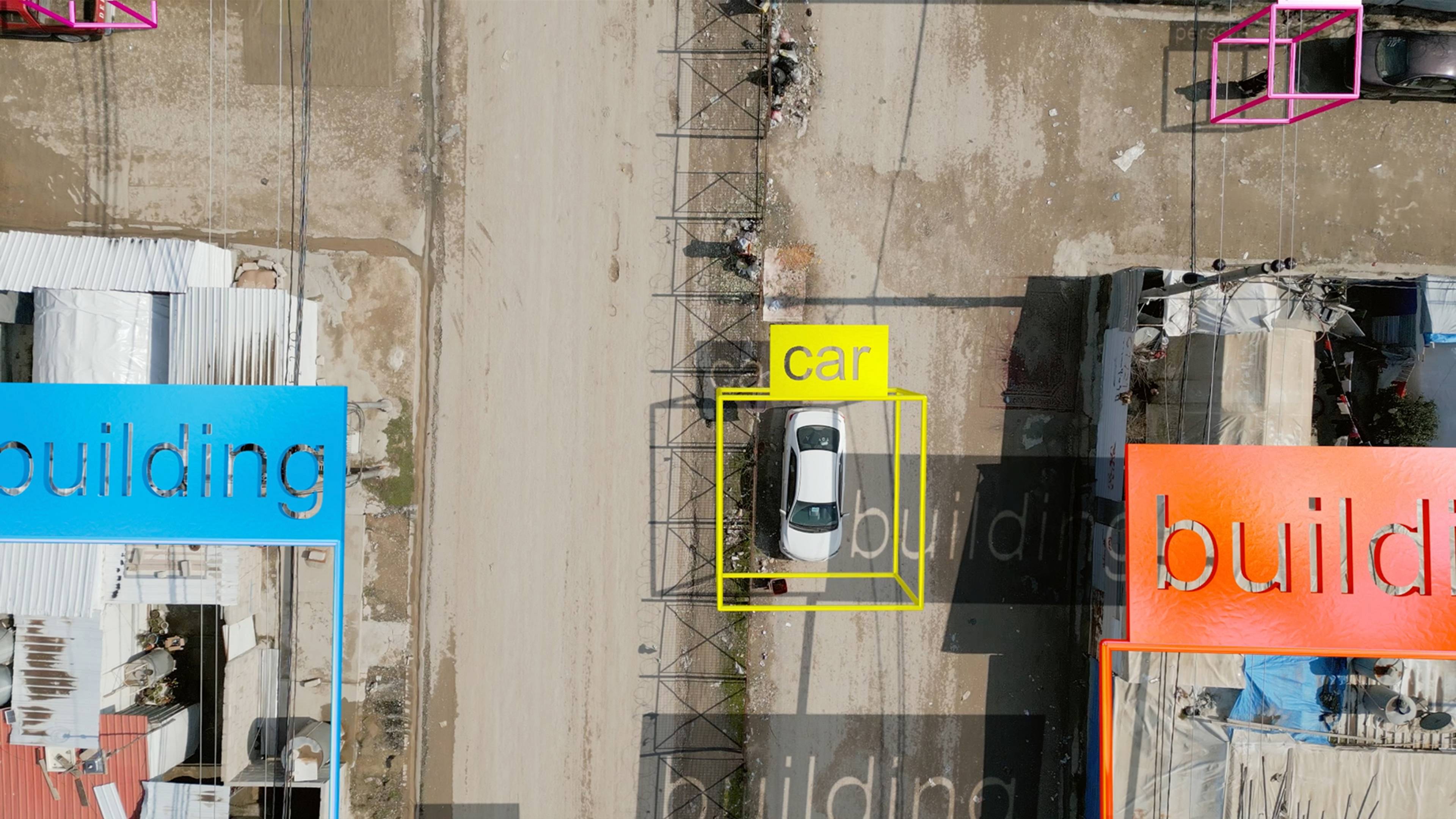

HS: It’s kind of obvious that AI is accelerating weapons development, big time, in Gaza and, before that, in Ukraine and Turkey; I was able to see its effects for myself in South Kurdistan, concerning drone development and targeted assassinations of critical journalists. In Ukraine, big Western arms makers are using the war as a low-regulation zone for R&D and extracting knowhow. AI has made a lot of warfare cheaper: Drones are much less expensive than fighter jets, and they are built on basically the same tools that surveillance states developed in the 2010s, like automated visual recognition. Camera drones partly come out of my world, the DIY video world, and have been repurposed for aerial terror.

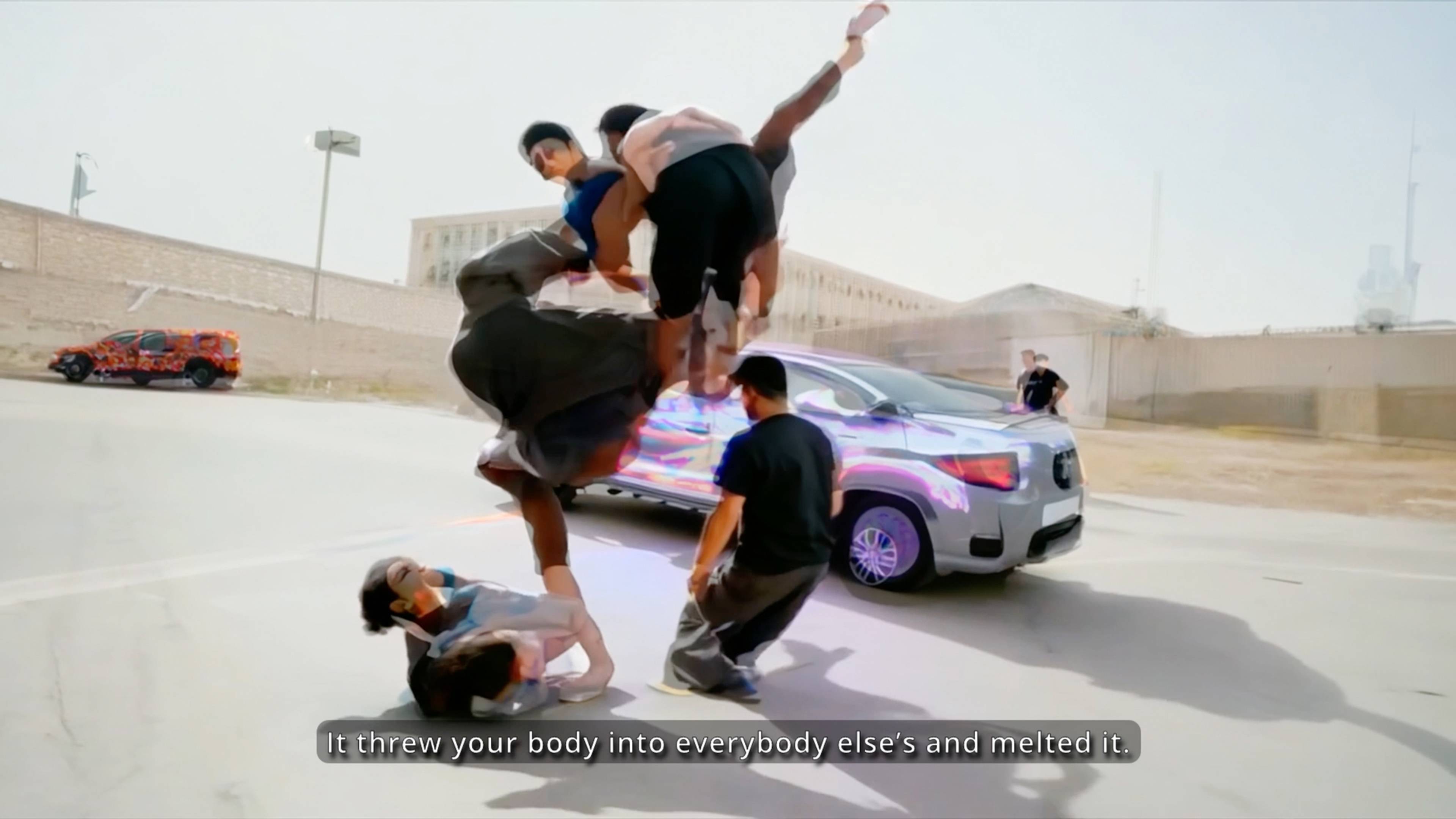

Stills from Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025, 13 min

All © Hito Steyerl, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Courtesy: the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul

GY: The language surrounding some of these technologies is very sinister, like Lavender and Where’s Daddy, AI-based systems used to target and kill Palestinians.

HS: I think you see the same approach in Trump’s meme aesthetics. The naming of Where’s Daddy, a software which told Israeli Defense Forces personnel when presumed low-ranking Hamas operatives got home, in order to bomb them while surrounded by their family and neighbors, also shows the desire to not only kill Gazans, but also to demean them – just as in Trump’s eliminationist Gaza AI slop. Being crass and cynical is no longer shunned, but openly celebrated.

GY: I’ve been thinking a lot about the connections between Italian brainrot, the viral AI trend, and Futurism – how Bombardino Crocodillo, one of brainrot’s recurring characters, makes references to bombing Gaza, and the fascist implications of it all.

HS: Bombardino Crocodillo was introduced verbatim as bombing children in Gaza and Palestine. As another example of fascist meme politics, Bombardino really reminds me of aeropittura, a Futurist painting style that aestheticized aerial bombing in Fascist Italy’s colonial warfare. The artist Simon Denny just did a really great lecture at one of our conferences in Munich about that whole historical cluster and its relation to Silicon Valley militarism.

Brainrot as a whole, though, is still more like Dada than straight-up Futurism, in how it collages incongruent stuff. Then again, Dada was never unambiguous. Fascist guru Julius Evola was a Futurist first, then a Dadaist. These movements were quite heterogeneous, right? On the other hand, Surrealist poet Koča Popović became a key Yugoslav Partisan general, and many members of these movements volunteered on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. These precedents may seem remote or irrelevant; for me, with my pre-internet brain, they are the lens through which I look at brainrot.

GY: Can brainrot ever be considered art?

HS: I mean, if we can define Maurizio Cattelan’s banana as art, why not? It’s already Italian brainrot all the way!

___

Hito Steyerl’s Medium Hot: Images in The Age of Heat is out now from Verso Books.

Hito Steyerl

“Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other”

MAK, Vienna

25 Jun 2025 – 11 Jan 2026