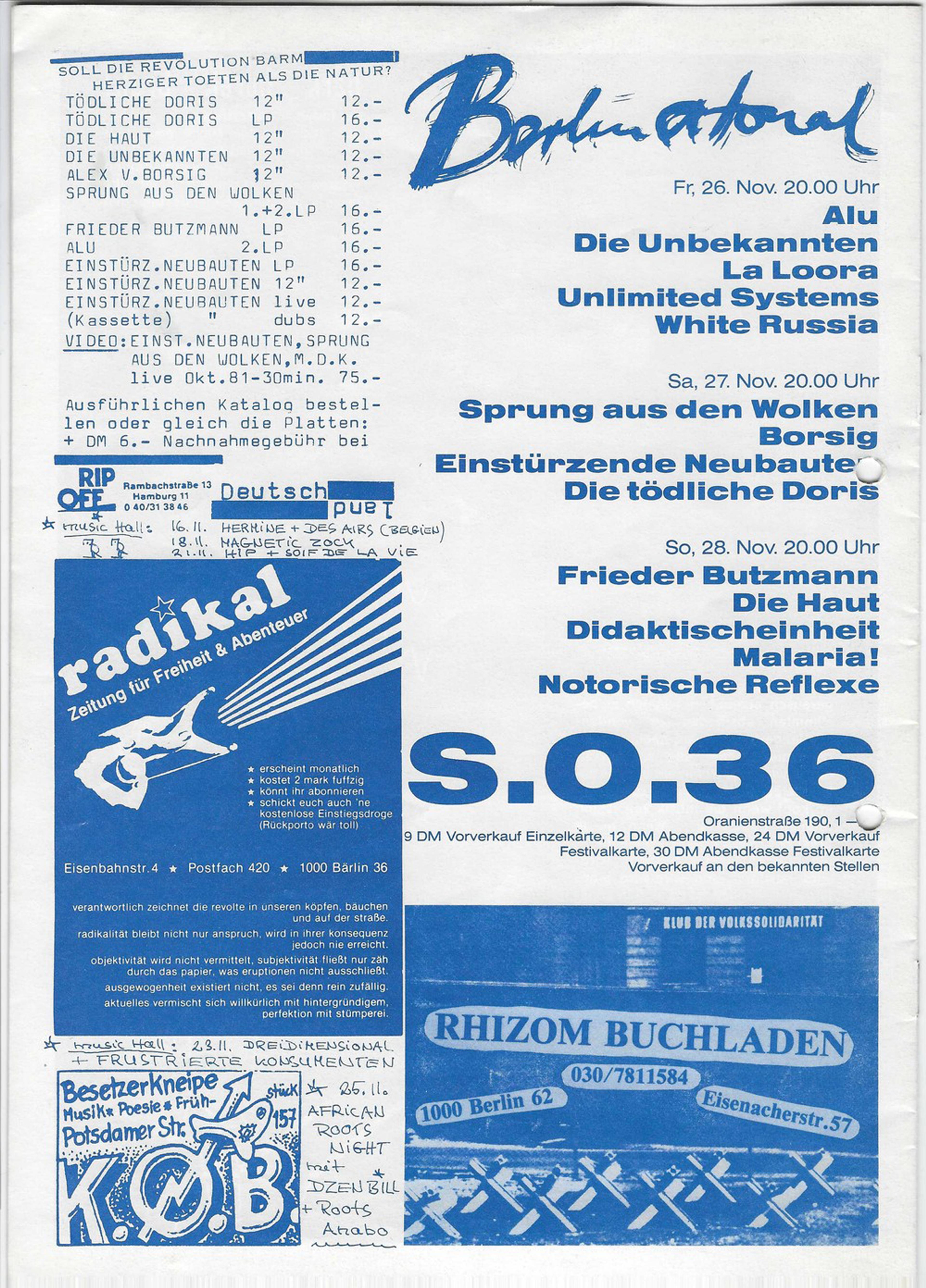

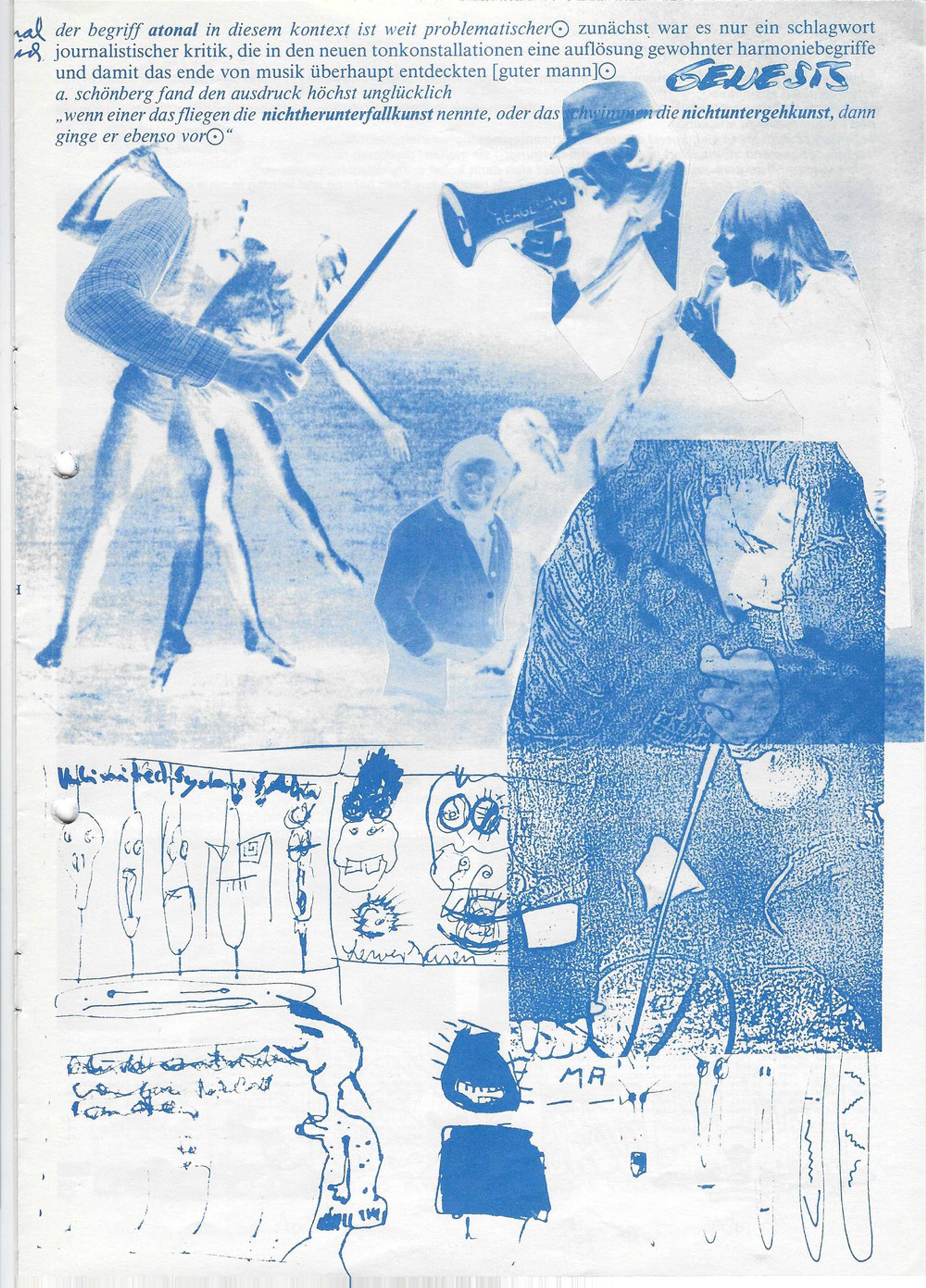

So long as Berlin has been a metropolis of postmodern music, Atonal has been one of its humming power plant. From its 1982 launch at the legendary punk node SO36, the festival’s formidable lineups of new-wave and noise acts – among them Einstürzende Neubauten, Malaria!, and Psychic TV – channeled an existentialist counterculture’s edgy, eruptive fantasies at a moment of deep malcontent. Its last paroxysm, fittingly, came months after the Mauerfall, when its founder, Dimitri Hegemann, committed to an altogether different industrial sound, opening the techno club and record label Tresor and soundtracking a new era’s blacked-out, anything-goes hedonism.

In 2013, Atonal reopened under new stewardship as neighbors of Hegemann’s dance outfit, in the steel-and-cement caverns of the decommissioned electricity station Kraftwerk. It quickly re-staked its place one measure inward from the city’s cultural fringe, albeit in a synthier, more computerized register. Last year’s program oscillated between disarmingly open compositions by Caterina Barbieri, Space Afrika, Laurel Halo, and KMRU and thudding, motorous DJ sets from Actress, Kode9, Mama Snake, and Skee Mask. As its directors playfully reformat the festival (2024’s billing, “OPENLESS,” was the first to be through-lined by themes), Atonal’s place in the global electronic vanguard is unlikely to waver – so long as it can keep its own lights on.

Patrick Kurth: Working year over year at Kraftwerk, how do you challenge its massive industrial architecture?

Laurens von Oswald: We know the space inside and out, but the proposition never simplifies. There’s no preset, and that helps us to safeguard against laziness. The exhibition we did in 2021 [“Metabolic Rift”] was, because of COVID, the first time we were able to activate it in a fundamentally different way. We took small “quanta” of people through the building in a kind of sequence. The first part was mainly in the basement, and the second culminated at the highest point in the building, which no one had ever seen before. To get there, you had to walk up this punishingly long stairway, where we had a piece by Tino Sehgal [This Ornation (Atonal Remix), 2018/21]. One of our objectives was basically to make the audience tired when they got to the end. Of course, people got pissed off: “Why are they making me walk up so far? Don’t they know I have bad knees?” All of that stuff. When they reached the top of the stairs, there was this really refreshing, literally airy piece by Cyprien Gaillard [Visitant, 2021], which looked like this big, eerie apparition. Using the building to change the state of the audience, that’s an interesting dynamic. Its not often you can “intentionally program” an audience to feel physically differently, and of course, that’s interesting for an artist to explore.

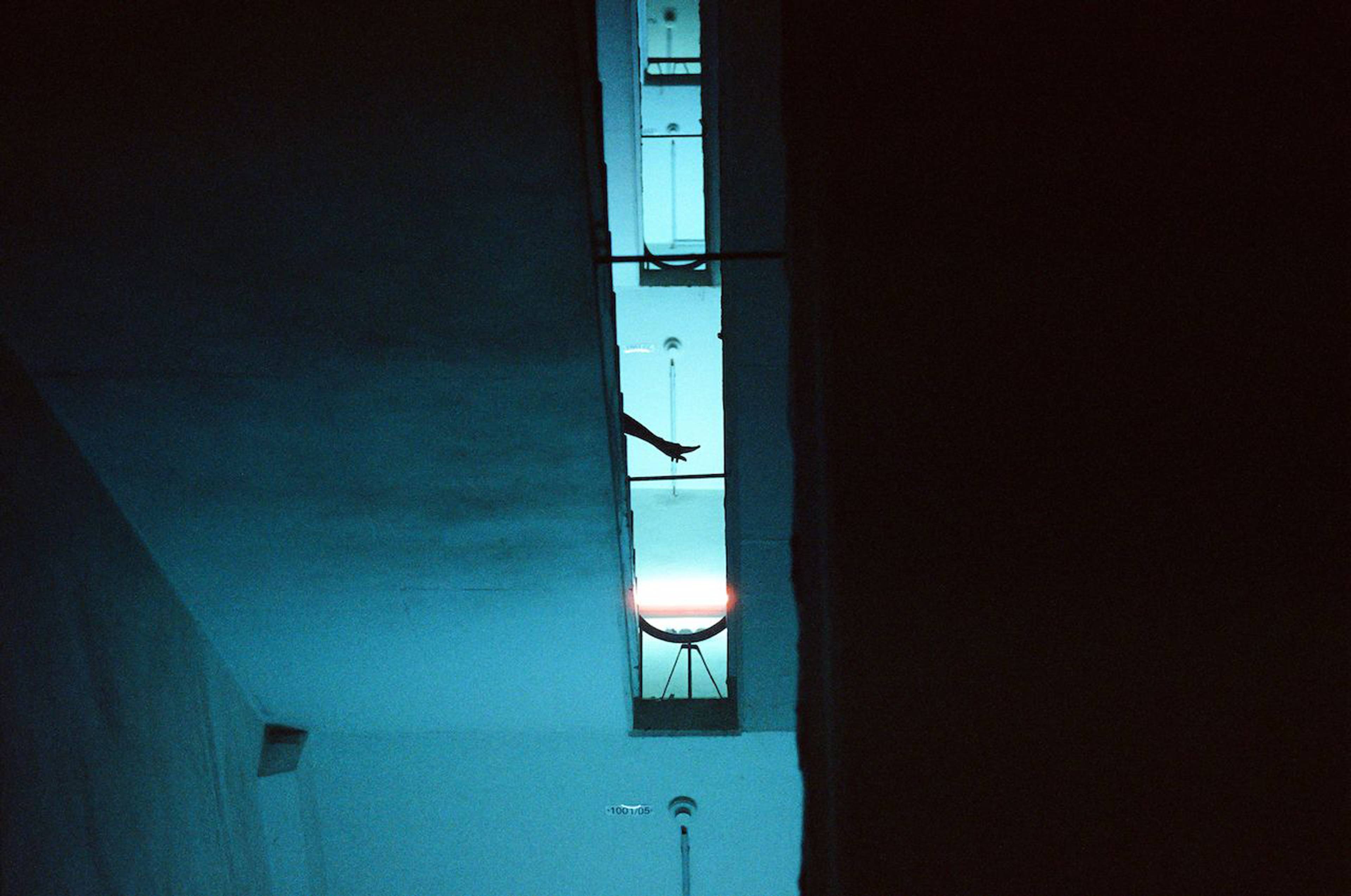

Tino Sehgal, This Ornation (Atonal Remix), 2018/21. Installation view, “Metabolic Rift,” Atonal, Kraftwerk, Berlin, 2021. Photo: Frankie Casillo

Cyprien Gaillard, Visitant, 2021. Installation view, “Metabolic Rift,” Atonal, Kraftwerk, Berlin, 2021. Photo: Frankie Casillo

That said, not every artist can do everything, and some are more flexible than others about understanding their work in different contexts. This is especially true in the art world, where people can be very guarded. We’re also contending with the fact that, when we design performances, we can’t do enough to a stage to make it feel different in a ten-minute changeover; on the other hand, we also don’t want audience members who come three, five, or ten days in a row to get bored. Fitting together how artists want to present their work with a curatorial or artistic understanding of how it should be seen, we end up doing a form of amateur chemistry. What comes before, what happens after, what goes with what? It could be like the stairs, it could be plunging people into darkness for twenty minutes before they are confronted with light; it’s sometimes as simple as putting two different elements together and seeing how they react.

PK: I think there’s quite a lot of audience trust in Atonal, or in this triad of organizer, venue, and whichever artist or artists someone is excited to see.

LvO: We don’t take this for granted. Ultimately, it’s what allows us to try things that we don’t know will succeed – it’s not a real experiment if you’re already certain of the result. That’s not to say what we try and bring together is under-designed. Its more to say that, once you involve an audience, once there is a real, embodied, and collective experience, in a specific place, at a specific time, there’s always going to be a variable in the equation. Its that living aspect that is generative of surprises.

Holy Tongue and Shackleton perform at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

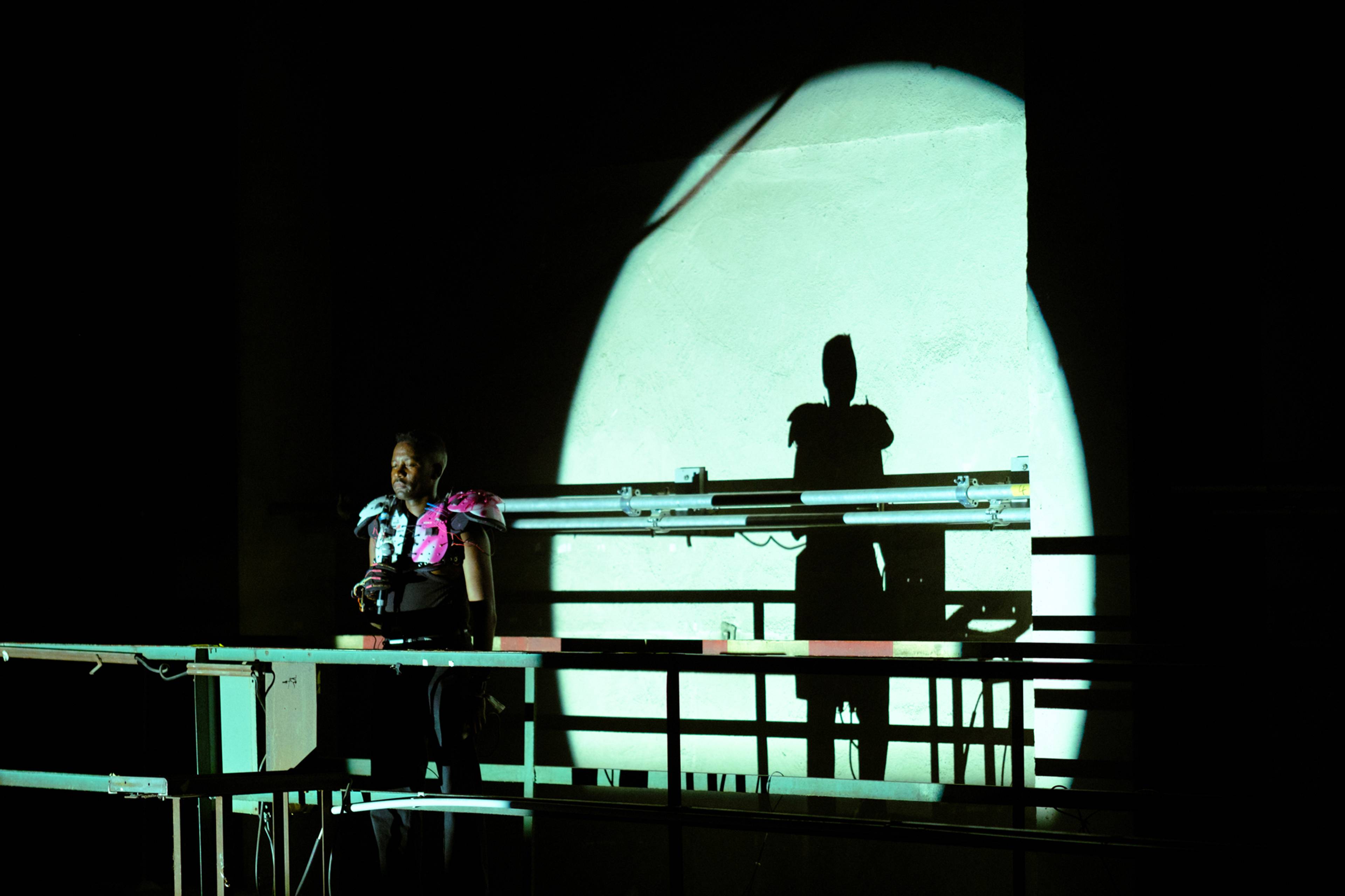

Spoken word performer during a presentation by Forensis and Bill Kouligas at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

Video during a performance by Saint Abdullah, EOMAC, and Rebecca Salvadori at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

Kelma Duran and FRANKIE perform at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Frankie Casillo

PK: Atonal also existed in the 1980s. To what extents have you tried to sustain or break from that legacy?

LvO: We’ve been able to study its history, and it’s something we really have a connection to – Dimitri [Hegemann], who founded the festival, is a close, trusted friend who we speak to often and has been supportive of our ideas. It was an incredibly creative time, and also, I think, one marked by a sense of being unobserved. A vacuum, I guess. In that initial era, shock was really relevant and powerful; but, four decades later, I don’t think it’s the most powerful emotion in creating a stark juxtaposition, artistically or curatorially speaking. Where it was maybe enough to scream unexpectedly or jackhammer through a wall, that’s something audiences are more used to now. The earlier editions also had a lot of Dada and playfulness about them, and the way that spirit interacts with the project’s obvious influence and meaningfulness is something we find really interesting. It didn’t take itself too seriously. That’s something we have tried to keep – to be an institution that takes work, artists, and the audience seriously, but doesn’t take itself too seriously. One of the ways we do that is by not force-feeding the audience with our intentions. Whatever we talk about internally, we don’t want to overdetermine how an audience member will react, or set up an expectation that they should have a certain response.

It’s also important to remember that the earlier edition of the festival was of its time, and we hugely appreciate its situational context, too. There was this West Berlin ideal that almost everyone who finds themselves here somehow has some longing for. But you can come out and say that the reasons David Bowie chose to live and work here were a historical anomaly – they’re not there anymore. All the things that made Berlin attractive even ten years ago are gone. The days of a tourist traveling to Berlin to consume culture on a student’s budget? Done! People who can afford to only work two or three days a week, renting an apartment for €500 and pursuing creative work? That doesn’t really exist anymore. Does that mean that that whole stream is dead and done? No! As long as a place has space for young people, then there is life in it. I don’t just mean physical space, but economic space – the space to try something and know that, if you fail, you’re not ruined or humiliated, but can try again.

Posters for Berlin Atonal, 1982, SO36, Berlin. All © Archiv Manfred Weiss

PK: Where do you understand Atonal to sit in today’s wider cultural landscape, both in Berlin and global experimental music?

LvO: Berlin has an oversaturated cultural scene, institutionally. From that perspective, it’s often hard to know where we stand. Sometimes, we’re designated as a techno festival – I have nothing against techno – but I don’t think that comes close to representing what we’re trying to pull off. Reputationally, I think we’re celebrated much more outside of this context, which is a continuing and annoying problem. Berlin specifically and Germany generally are culturally well-funded organisms, and every single politician at every single opportunity expresses how important culture is to the fabric of Berlin. But, from our position, the facts as we see them are that we have a very difficult time keeping the festival afloat. There’s no clear pathway to having it funded, despite what is said in government. It’s got minimal interest for sponsors, and its ambitions are outsized with respect to its commercial possibilities.

So, that tends to pose some existential questions. Are we actually offering something meaningful? And are the audience and the context correct for it? Our experience is that the audience is there, it’s proven, but the culture itself needs to be taken more seriously. It still feels like something that could only happen in Berlin. I guess it feels like there’s less and less that could only happen here.

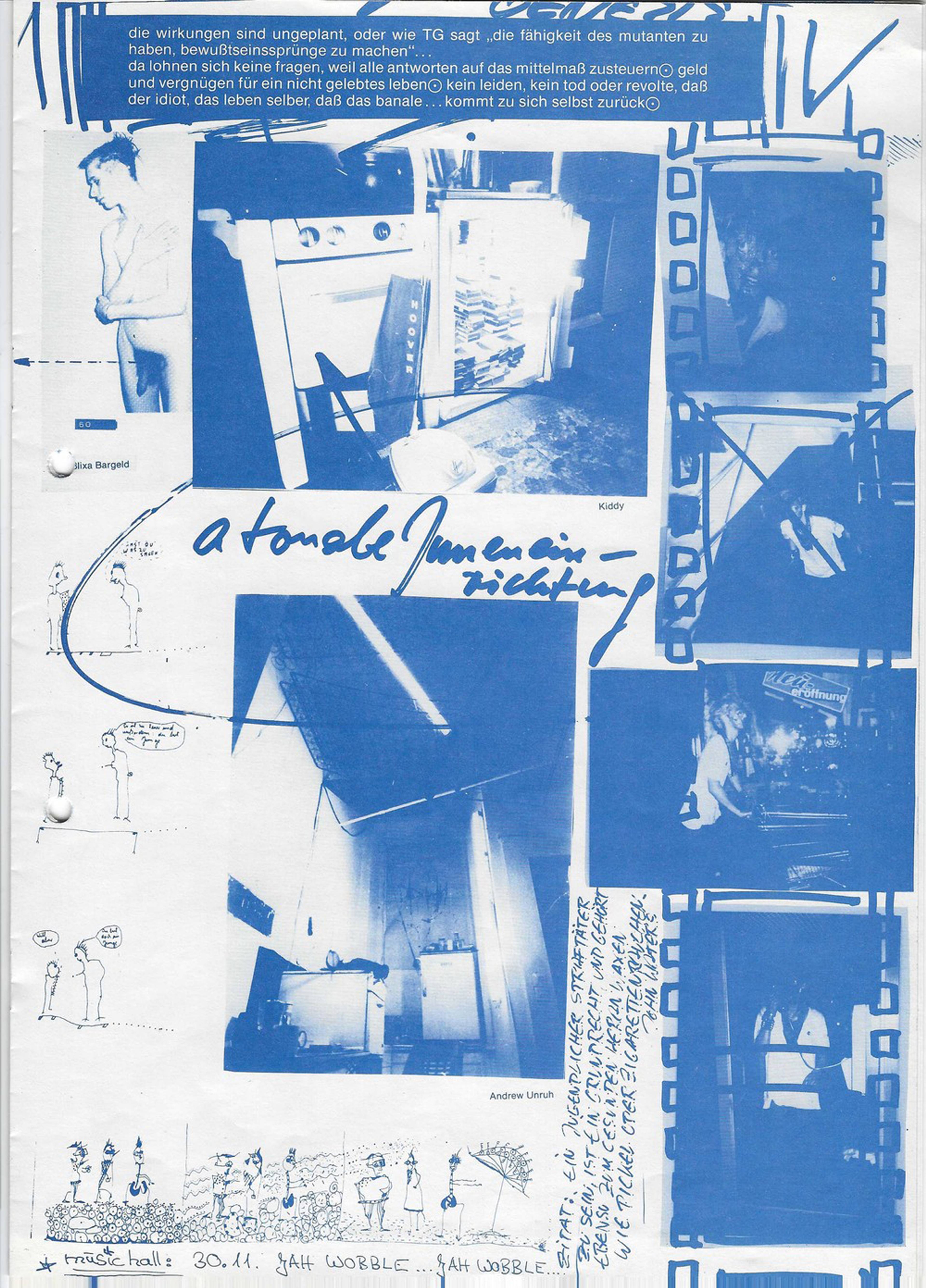

Lord Spikeheart performs at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

Emiliano Maggi of Canzonieri, performing with Lord Spikeheart and Lara Damaso at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

Nkisi performs at Atonal, 2024. Photo: Helena Majewska

PK: As Atonal turns into a biennial, what sets apart this “off-year” event, “OPENLESS?”

LvO: Last year, we had ten days and 300 artists and an exhibition and a concert program and and and and and. Artistically, we felt very fulfilled, but it felt like we’d reached the limit of a format – more wouldn’t have made things better. So, we want to focus on the five-day format that has worked so well, and, in the off years, to scratch that itch of doing things that don’t fit. Essentially, these are projects that we couldn’t execute with the same level of attention if they were shrouded in the noise of the normal festival. For “OPENLESS,” we wanted to build nights specifically around thematic cores. That’s something we were allergic to up until now, because we thought that trying to massage artists into an overarching concept would overdetermine things. Sometimes, audiences benefit from these frameworks, but mostly, they’re decorative ways to help people feel comfortable when they don’t need to feel comfortable. In this instance, we wanted to take thematizing seriously, not as a conceptual principle, but as an organizing one. The nights unfold operatically around some sort of thread.

PK: Can you unpack one of the nights’ themes?

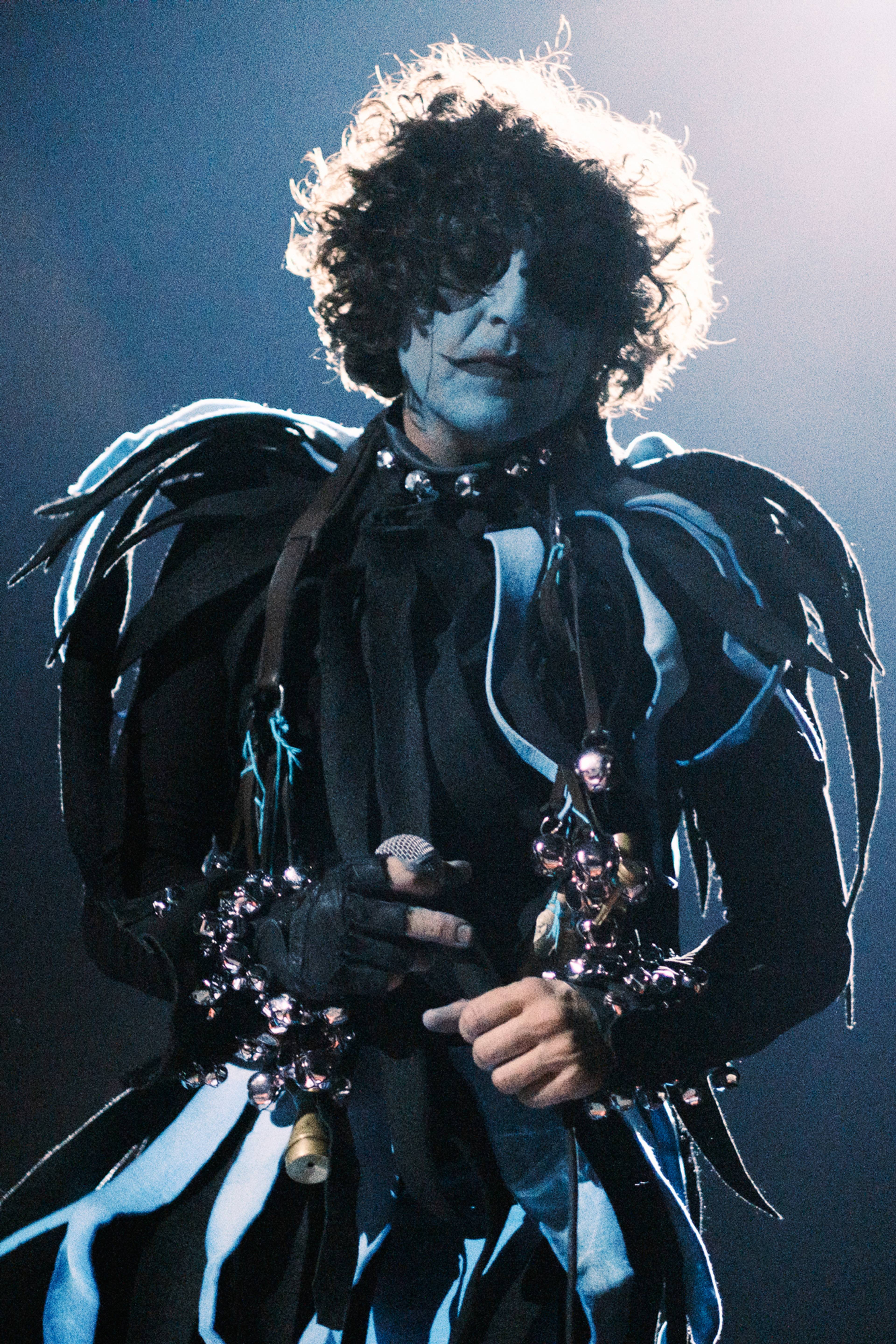

LvO: Night two [Saturday, 24 August] is a good example: It’s based in a project we began in 2020, when, just before the pandemic, we went to Dakar with LABOUR [artist duo Farahnaz Hatam and Colin Hacklander], who had been working there for some years to document this drumming tradition that’s in every aspect of Senegalese life. One of its modern protagonists was Doudou N’Diaye Rose, a griot musician whose family’s entire life is structured around this form of drumming. Each one of his forty children is, in some way, still contributing to this mission of storytelling. When he passed away in 2015, there was a realization that none of what he had done had been documented or really presented internationally. So, we took sound engineers and recording facilities and spent about ten days just outside of Dakar, recording the rhythms that Doudou had invented and that weren’t notated, to create an archive that could eventually be donated to the Smithsonian or Senegal’s IFAN [Museum of African Arts], if we were lucky. It was also a kind of social challenge, in that we had to bring the different strands of his family together to collaborate on this thing. We also didn’t want to do what we’re used to in the West, just extracting from these traditions and including them in our work guilt-free. So, we also invited several artists to create new music, and we published a series with the London record label Honest Jon’s, as well as a film that documents some of this story. We were never able to have live interaction with this really special art form because of COVID, but now, we’re going see all of that come together for the first time, in one six-hour, operatic block. Performances by electronic musicians from the Western tradition will be punctuated with presentations from family members drumming famous parts of Doudou’s repertoire. The whole thing will culminate in this hybrid version of a Tannebier – the ultimate improvised, street-based event which has sabar [a tall, wooden drum] at its center.

Members of Family N’Diaye Rose performs at Atonal, 2024. Photos: Helena Majewska

PK: As Atonal’s format changes, when will you know the festival has run its course, or changed so totally as have become something else entirely?

LvO: Well, you have to ask yourself, what is the thing in the first place? There’s very few music festivals in the world, maybe none, that we feel are really comparable to what we do. Even by nature of everything happening in one place, at Kraftwerk – that’s usually reserved for outdoor festivals, whereas city festivals usually are spread among different venues, different spaces. We’re fortunate that we don’t have to do that, and we can concentrate the first-person perspective into an enclosed universe. We also think that, by breaking some of the monotonous organizational cycles, we’ll give ourselves more time to reflect, without chasing our tails the whole time. That’s made us feel more confident about the direction of the festival in its full form, and the continuous realization that we have a really trusting and unique audience.

The only thing that we feel limits us is not our ideas; it’s just time and resources, which are the things we try to mitigate against. I think things will run their course if we feel that we don’t have what we need to make the motor run. Identifying in artists the messages that they’re trying to represent and providing a context that isn’t usually there for them also involves risk. If that element of risk somehow becomes too obstructed, that would also be an indicator that things aren’t moving anymore, that they’re not fluid and in flux in the way that they need to be. It’s an experiment in chemistry, after all.

Portrait of Laurens von Oswald. © Christopher Bouchard

___

“OPENLESS”

Kraftwerk, Berlin

23–25 Aug 2024