In the last essay he published before passing away on 23 October 2024, Gary Indiana wrote about photographs: “We all live at least one or two lives that we subtract from our biographies. Areas of un-revisited, unhealed pain or such monumental nothingness that they’re not worth remembering. Then, infrequently, some evidence turns up, often photographic evidence. You are seized, suddenly, by a grisly species of curiosity.”

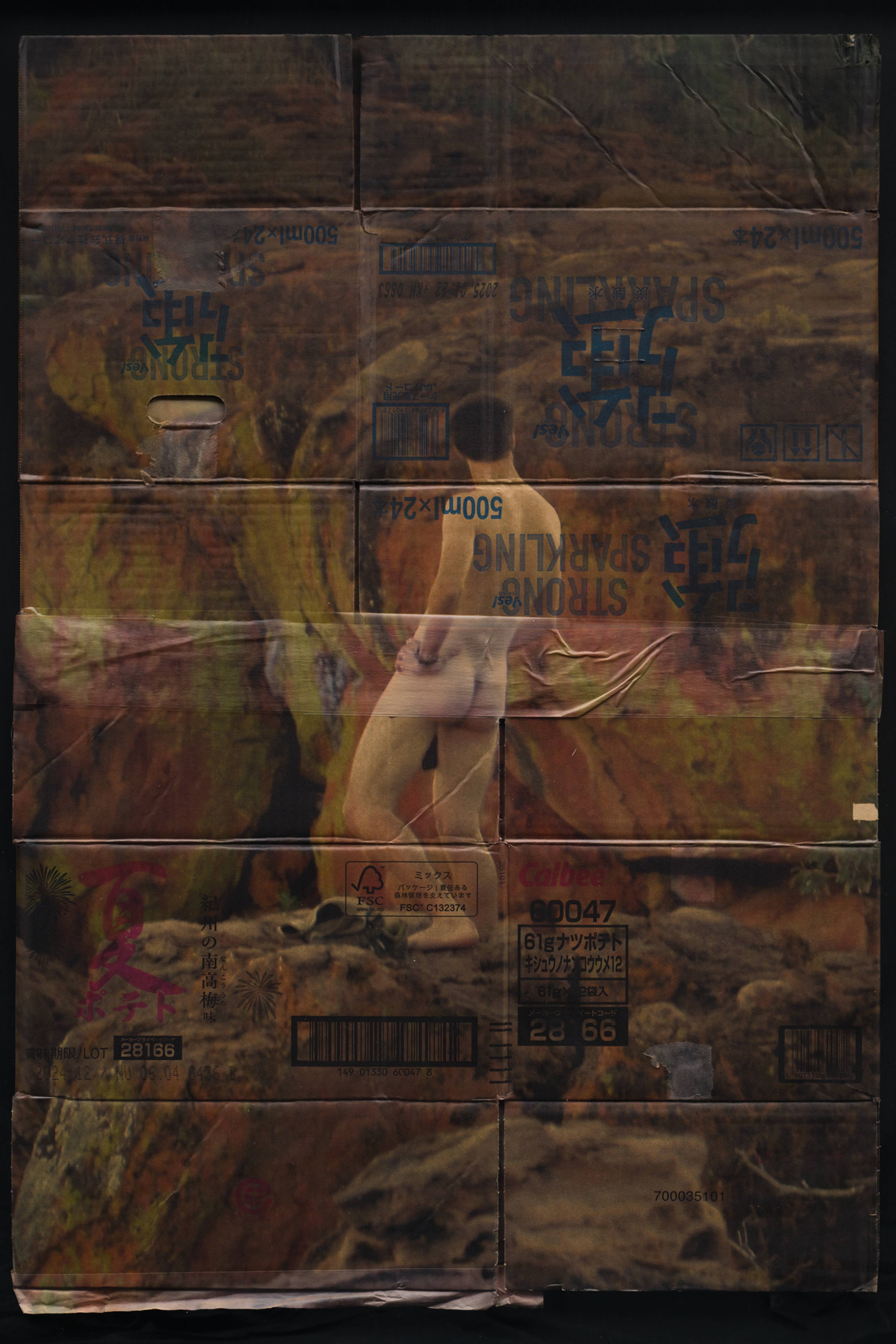

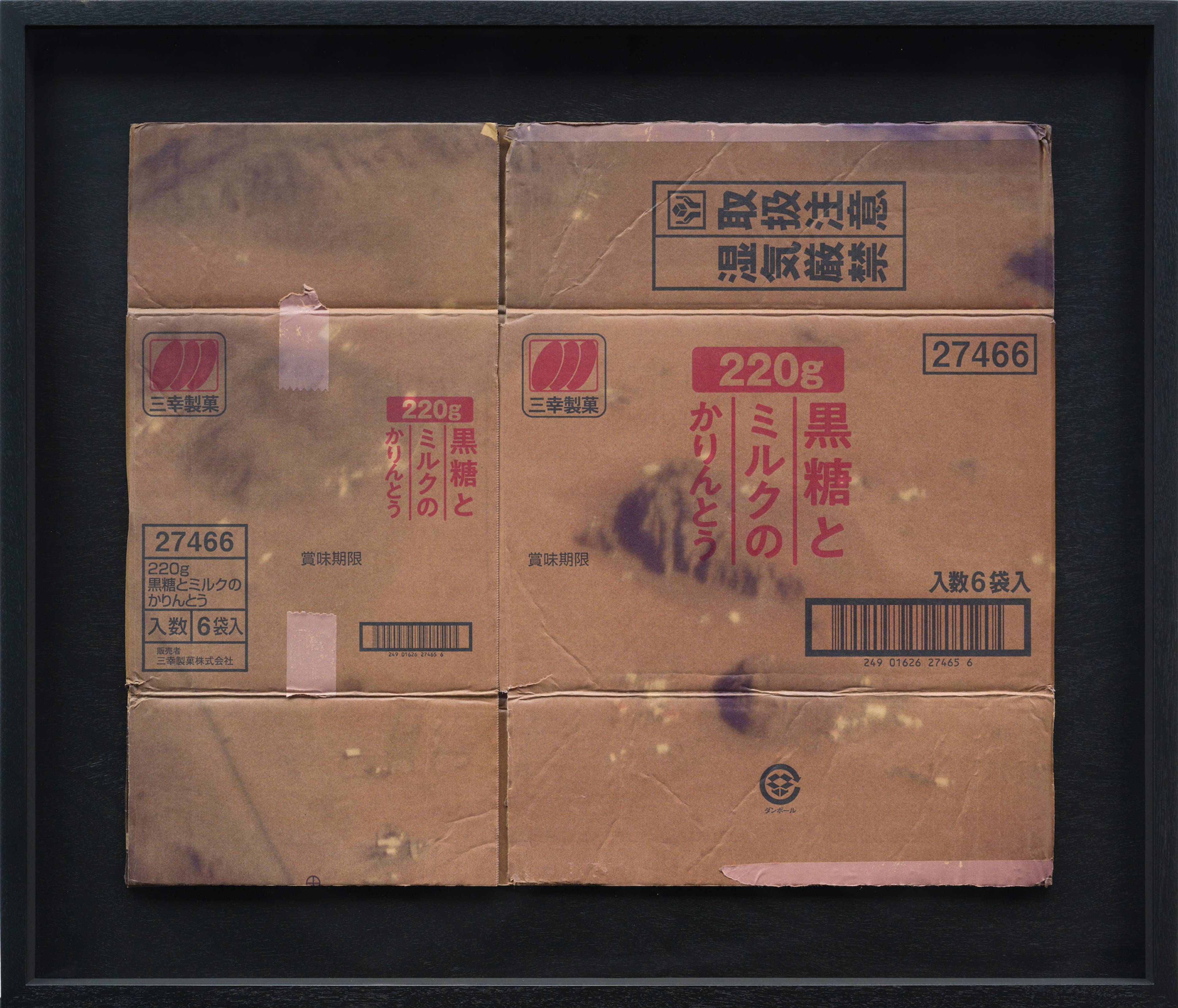

Born in Japan and now living in New York, artist Taro Masushio’s exhibition “Pass” at Empty Gallery, Hong Kong is replete with photographic evidence, but contains little of facts and does not reward undue curiosity. Masushio’s reprinting of his father’s amateur travel photography on the cardboard of care packages shipped across the world from father to son conjures a haptic, material intimacy mediated by impersonal logistics networks. A series of sparing, high-contrast still-life photographs catalogues enigmatic objects sourced intuitively from his father’s belongings and the artist’s own collection – a book of Rimbaud’s poetry, a pair of male Ainu figurines, testosterone supplements, photo paper, a darkroom safe light. The effect is disruption of the impulse towards certainty in meaning-making, the recognizable objects utterly drained of their indexicality, despite their unambiguous familial, autobiographical, and sexual connotations.

Jamie Chu: How did you start putting together the images and materials for this exhibition?

Taro Masushio: It’s something that I’d been thinking about for a long time. I’d seen some of the images when my dad first took them [on a solitary trip around the world in 2023], and some of them I discovered as I began working on the project more intently. The cardboard boxes functioned as an intermediary between myself and my father. Every once in a while, he would send me things from Japan. For example, during the pandemic, he saw on the news that the shelves at grocery stores here in New York were completely empty, so he sent me some dried noodles, which helped me get through that time – in more ways than one. So, they really came from my engagement with my own life. I see it as bricolage, and, by extension, as not simply a theoretical question of living, but a concrete one as well.

Of course, through this act of sending something to someone, things enter into a whole network of index, transfer, and transaction, accumulating marks, tears, stickers. I was thinking about these overlapping movements taking place, tracing my dad’s own movement around the world, and the movements of the containers themselves.

Untitled (CB #15), 2024, UV print on found cardboard, 87.6 x 97.2 x 7.3 cm

JC: The photographs impart a smooth, shimmery effect on the recycled cardboard packaging. Was the UV-printing process difficult?

TM: Part of the challenge was thinking about how the material interactions work with and against each other. I mapped everything out as much as I could, imagining the ways in which existing colors, symbols, tears. and marks on the cardboard would coexist on the surface with the print images. I was particularly interested in the interruptions of smooth imagery that draw you into the haptic. But, since the simulations aren’t perfect, there were still elements of chance, of surprise. I accepted whatever the result, in part because I didn't have that many cardboard boxes.

JC: How did you toggle between these two modes of image-making, this chance-based, imperfect print medium and your very meticulous, controlled, and singular still-life photos?

TM: It involved a lot of intuitive processes. The kind of technical dimension of the two forms can allude to different attitudes, but they don’t necessarily differ too much – across the processes, I trust my decision-making. While the still-lifes are meticulously constructed, it isn’t that I was exhaustively going through my father’s belongings; when I saw [a Japanese edition of] Rimbaud’s poetry book, I knew I wanted to photograph it. There is an element of chance encounter to that as well.

The arrival of meaning is not a linear process; it forces you to take detours, unexpected turns, and you sometimes find yourself at dead ends, where the humor has a tautological effect, being both the meaning and its cancellation.

JC: How do you think about an “informal/imaginary archive” in relation to building an alternative storage space for these objects and their relations? And how does photography mediate between different worlds, forms, and time periods to construct an account of a “self?”

TM: Alex Lau from Empty Gallery came up with the phrase. He is one of my few interlocutors who has deep intimacy with my work and thinking. My approach was also described recently as “fractal,” which I think gets to my methodology in that, like you were saying, these kinds of facts aren’t necessarily what is being foregrounded; instead, it’s the idea that what is already fictional is being fictionalized and folded in on itself. Like the idea of the relationship between a father and a son.

In the case of this exhibition, this fractal use of the imaginary/informal archive is a re-dramatization of the archetypal story that has lasted for centuries, from Greek mythologies to psychoanalysis. I think there is something kind of funny about this blatant use of an all-too-familiar story, like psychosexual development gone awry. I’m interested in this comedic obviousness because I think it complicates the process of meaning-making.

JC: I noticed the comedic gestures in your image groupings, like fireworks, the Rimbaud book’s floral cover, and a Rococo ceiling all next to each other. But humor is also enigmatic, because you can't explain it; some people will just never get it.

TM: There is something about humor that epistemologically destabilizes our capacity to know. The arrival of meaning is not a linear process; it forces you to take detours, unexpected turns, and you sometimes find yourself at dead ends, where the humor has a tautological effect, being both the meaning and its cancellation. We are meaning-making machines that are constantly trying to make sense of the world, even when it’s impossible. Maybe what art does is allow us to sit with the discomfort of the unknown. Everything becomes exotic at the limits of one’s own subjectivity. It’s similar to how queerness continues to maintain its loose contours – it can’t be simply defined, but has to be placed alongside the negation of things that are un-queer to have some kind of working meaning.

Views of “Pass,” Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, 2024

JC: This destabilizing space is both the entry point for the erotic and what contains “the self” in your autobiographical approach. The landscape prints are quite discernible as landscapes, and there is little ambiguity in the subjects of the still-life photographs. At the same time, the longer you look at the images, the more they fizzle at the edges. The formal enigma actively dispels a sense of ownership over the narrative. How conscious were these affective decisions in your process?

TM: I’m very glad to hear this because my concerns tend to be more abstract and formal than strictly biographical. I think what is analogous to the erotic that arises from hermeneutics is a drive of some sort, this sense of movement, where the meaning of the thing cannot be found in a single locus of understanding, which places one in a dynamic situation. It is fragmentary, tentative, and contingent by nature. It is almost like a pact, that I am trusting the viewer to take this and run with it, and there is a certain sense of vulnerability in that trust.

JC: How do you understand intuition in your art-making?

TM: It’s a process of thinking. There are thoughts in the recesses of your mind that feel more like approximations and do not manifest as concrete, articulated language, but when you see them in the form of artworks, they become articulated thoughts. I think that’s the difference. I don’t subscribe to the notion of “in the beginning was the word”; I think in the beginning was form.

Untitled (CB #17), 2024, UV print on found cardboard, 70.5 x 82.4 x 7.3 cm

___

“Pass”

Empty Gallery

21 Sep – 30 November 2024