Adina Glickstein: As a kid, I went to this day-camp for nerds where they let us play around with CAD software for interior designers. This was the early 2000s, so it was super primitive, but I was instantly drawn in by the possibility of rendering 3D space online – moving the little chairs around the virtual living room. How does your background in architecture inform design for digital spaces? And what kinds of possibilities do you find in the virtual world that aren’t available in “meatspace”?

Manuel Rossner: Being exposed to those technologies when you’re young is really powerful. For me, it was gaming with friends that introduced me to digital 3D spaces. We would meet for LAN-Parties to play Counter Strike , a first-person shooter game. Already, back then, I was curious about pushing the limits of the game. For example, there was a mod – a user-built hack – that turned all players into chickens. And there was another hack that turned the play area from a clichéd warzone into an overscaled kitchen. Playing with the possibility that “reality” could be something entirely different has definitely continued into my present artistic practice.

During that time, I also read a text by Oscar Niemeyer about how architecture is able to transform society. The discussions around modernism were particularly inspiring to me. And yet, in my portfolio for the art academy, I had built a house made out of butter on metal ground and melted it with a Bunsen burner. Without knowing it at the time, I had decided to let go of the physical limits that architects face.

AG: How has your practice changed since you started in 2012? What new tools and approaches have you adopted?

MR: The idea of a digital world adding another layer to the physical is really constant in what I do. That hasn’t changed since the first shows I made with Float Gallery in 2012. I am now working on a Metaverse called Realworld. It links all my geo-located artworks in one virtual world. I can really merge everything I made since the beginning, even on a technical level, thanks to the technology that’s available today. Within this new Metaverse, you’ll be able to walk from the show I curated 10 years ago in Offenbach to my most recent projects in Hamburger Kunsthalle, KÖNIG GALERIE, and Grand Palais Éphémère in Paris. Of course, NFTs, machine learning, and virtual reality glasses have influenced my practice. At the same time, merging digital and physical realms remains the focus of my work. Recently, I started producing physical artworks based on digital drawings I create in VR. Switching between the two worlds gives the artworks another dimension.

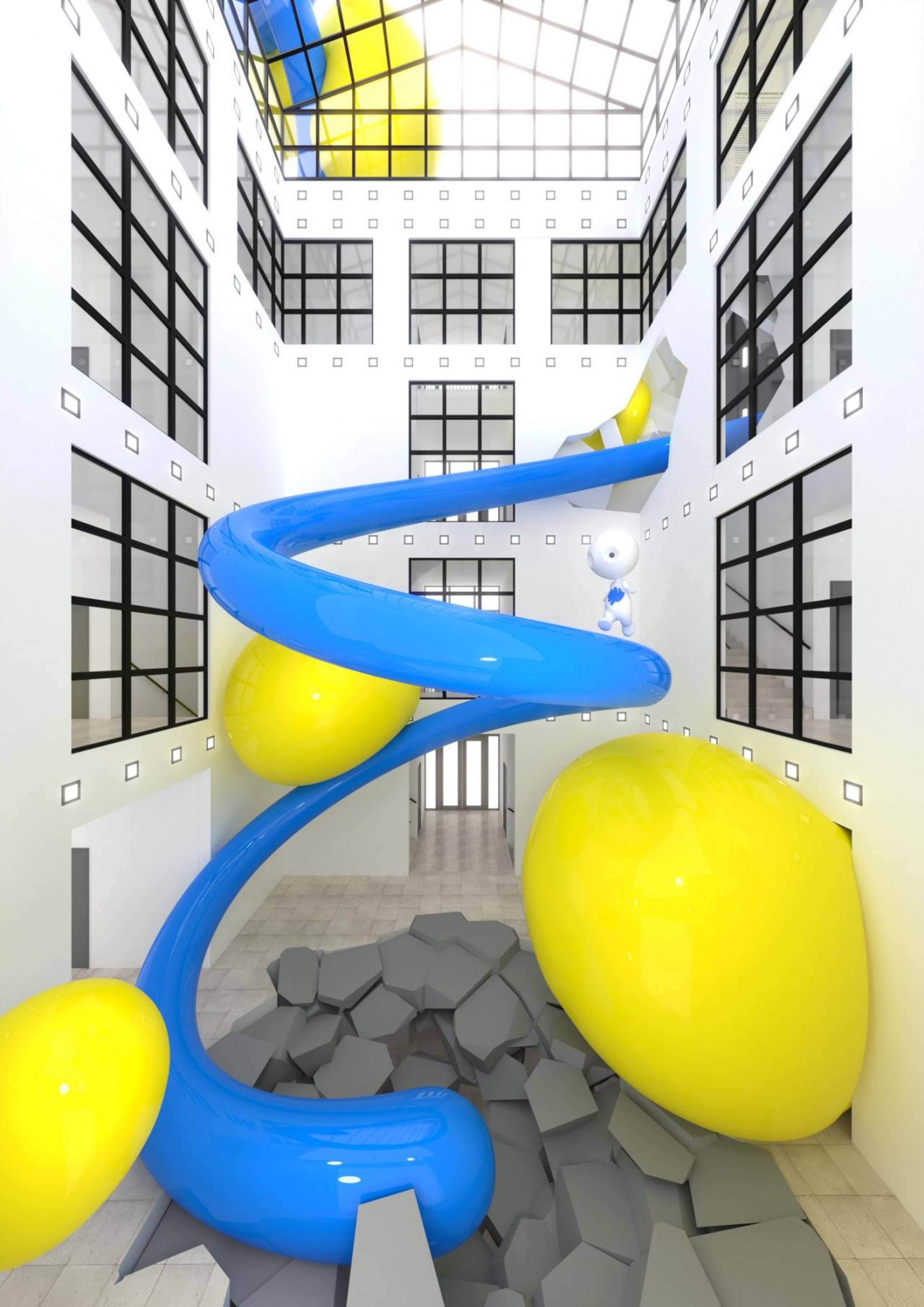

View of Manuel Rossner, Surprisingly This Rather Works, 2020, KÖNIG GALERIE, Berlin

I’m more and more astonished by the ways in which technology shapes society. There’s an interesting passage in Jaron Lanier’s book, Dawn of the New Everything, where the VR pioneer talks about the early days of the internet. There was a moment when the engineers decided that everyone can make hyperlinks leading everywhere. They could have programmed the protocols in such a way that pages you link to need to accept your connection. If, for example, news pages could charge users when other sites refer to them, we might have a totally different digital landscape today. Nobody can say what that would look like, or if it would be better or worse. But tiny decisions in the basic design of new technologies have a huge impact. That’s also why I’m so curious about the blockchain. I think the more that people experiment with it, the better it will develop in a purposeful and diverse way.

AG: For our readers of a less techie persuasion: what’s a Metaverse?

MR: The Metaverse is a spatial digital world; a new iteration of the internet mixed with virtual reality. Movies like Ready Player One or even The Matrix are often mentioned as references to explain it, so a dystopian touch is somewhere in there. But the definition is still quite open. So many projects are labeled as “metaverses.” At the same time, big tech is working in that direction. Facebook and Epic Games, the company behind Fortnite, invest in Metaverse projects. Because I’m working with physical architectures and on physical objects, I’m interested in a version of the digital universe that is linked to the physical world.

View of Manuel Rossner, Hotfix, 2021, Highsnobiety, Berlin

AG: Talk more about your physical production processes? What kinds of things are you making, building, and doing offline?

MR: My approach to the digital space is about materiality: everybody knows what wood looks and feels like, what happens when you break it and burn it to prepare food, and so on. Over centuries, architects, artists, and designers have shaped the way that materials like this are used. How does that translate to algorithms? Usually, you paint walls white because that’s the most neutral and bright way to do it. In the digital space, you’d assign random colors to new objects, because it helps you distinguish different elements, and you can change the color instantly anyway. If you put reflective materials in a colorful space, you’ll see immediately where the reflection comes from. That was an important part of reverse-engineering physical light for computer graphics. For my 2017 solo show “Ultralight Beam,” I built such a setup, called a Cornell Box, inside a physical gallery.

View of Manuel Rossner, Ultralight Beam, 1822 Forum, Frankfurt. Photo: Neven Allgeier

My more recent works play with the idea of painting. I wear VR glasses and draw lines in virtual versions of existing buildings, like the Hamburger Kunsthalle and Grand Palais Éphémère in Paris. Often, my lines crack the walls, or you can throw my work around and jump on it. That obviously wouldn’t be possible in physical space.

Going in the opposite direction, I also transfer the digital drawings in physical space with CNC milling. The same file that I melt in digital space is sent to a milling machine [a computer-networked shop tool] and produced, so it resembles the virtual object so closely that it’s hard to tell the difference. It wouldn’t be possible to reach the same degree of accuracy with human skills. The first artwork I made with these shapes was called You must change your life, referring to a Rilke poem about an ancient Apollo Torso, which was so perfect that Rilke himself felt an urge to improve only from looking at it.

Manuel Rossner, Surprisingly Blue, 2021, KÖNIG GALERIE, Berlin. Photo: Roman März

The point is that it’s impossible to keep up with technology, at least in performing specific tasks. The philosopher Byung-Chul Han uses the term “signature of the presence” when he speaks about the sleek surfaces of the iPhone and the perfection of digital surfaces. Even horrible scenarios become aestheticized, avoiding all friction. That, I think, redefines the human experience in the 21st century.

AG: I agree (and am on the record as a Byung-Chul Han fangirl), which must then incline us towards taking a broader view of any emerging technology. With that in mind, do you see useful or meaningful applications of blockchain beyond the speculative asset bubble of NFTs?

MR: I think that blockchain technology and non-fungible tokens structurally make so much sense that they’ll stay around. The current internet created a couple of separated and isolated web giants. The decentralized internet, which is based on the blockchain, supports exchangeability. You can buy an NFT representing a virtual plot of land on one website and build on it on another. I’m not saying there are no difficulties, but that different paradigm alone is very powerful. The current internet offers free access to knowledge and information, which is an incredible achievement. At the same time, the current structure makes independent creators feed the big platforms. Decentralization offers a new way of building digital worlds, and I’m interested in integrating these possibilities in my work. I’m especially excited about my digital work “How Did We Get Here?” for Hamburger Kunsthalle, which will become the first NFT in their collection. Maybe a digital landscape with more public and decentralized ownership is still possible?

Manuel Rossner, How Did We Get Here?, 2021, Hamburger Kunsthalle

___

Rossner’s digital exhibition space New Float is geolocated at Berlin’s Kulturforum, on the build site of the Museum of the 20th Century.