There is a point, as you visit the 13th Berlin Biennale, after which your mind stops perceiving the art and begins to wonder what went wrong. I can’t go on, I’ll go on, I muttered to myself at the former Moabit courthouse on Lehrter Straße. I was dragging my feet past well-meaning but mostly unmemorable art nullified by brusque hangs and minimal contextualization. A curator’s job is to select, edit, and decide what deserves to be seen: to identify, to platform, and to give space. Yet here, where there might otherwise be breathing room, there is only a kind of exasperated sadness.

I don’t want to add my voice to those legions who want to hasten the death of international mega-shows. In theory, there is nothing wrong with this exhibition’s guiding concept of the “fugitive.” I informally asked some peers of mine. What did they think of this year’s Berlin Biennale? None of them had seen it. When the flagship exhibition of the German capital failed to interest the artists, researchers, and curators who live in the city, it’s a signal that something has gone utterly wrong.

From left to right: Htein Lin, Prison Paintings from the 000235-series, 1999–2003. © Htein Lin; Stacy Douglas, Law Is Aesthetic: Trope, 2025. © Stacy Douglas. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

Elshafe Mukhtar, When Bots Rule a Great Nation, 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Elshafe Mukhtar. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

Granted, it is a challenge to organize a biennale in Berlin in 2025. Aside from the regular logistical hurdles involved in any large show, this exhibition had to reckon with the extraordinarily negative public opinion that has laced the city of late. Biennales are inevitably referenda on the cultural life of a given place. Take their word for it: The Biennale would like to “open up a dialogue with the inhabitants of the city.” As much as I would like to argue the opposite, the image of the city I get here is that of a cultural life in crisis.

Since the Biennale’s inception in 1998, Berlin has gone from being a poster child for post-socialist creative lawlessness; site of ruin porn for Leica-wielding tourists; and, after the Great Recession, as other Western cities fell into neoliberal acceleration and digital surveillance, it became a magnet for a mobile, internationalist creative class upholding the values of relative autonomy. Yet what has the city come to mean? Xenophobia is rampant, structural, and perceivable in the smallest of daily interactions. Since 7 October 2023, Berlin has become shorthand for state repression, remilitarization, and revanchism of a Western European bent. Tourism to Berlin has gone down: The same people who once flew in on EasyJet for a weekend now avoid a place in which liking an Instagram post can get you deplatformed or lose you a gig, where arts funding has been slashed – a place where pointing out what is obvious to the rest of the world is criminalized. Exaggerations or not, this is the image people have of the place; they contribute to a climate of fear that in turn shapes public opinion, which is the general atmosphere this event must now reckon with.

From left to right: Panties for Peace, Panties for Peace Emblems, 2010/25; Chaw Ei Thein, from the series “Artists’ Street,” 2025. © Chaw Ei Thein; Exterra XX – Künstlerinnengruppe Erfurt, Selection of performance objects, c. 1988–1993. © Exterra XX – Künstlerinnengruppe Erfurt. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. Photo: Diana Pfammatter, Eike Walkenhorst

From front to back: Anawana Haloba, Looking for Mukamusaba – An Experimental Opera, 2024/25. © Anawana Haloba; Sammlung Hartwig Art Foundation; Margherita Moscardini, The Stairway, 2025. © Margherita Moscardini; Gian Marco Casini, Livorno; Armin Linke, Negotiation Tables, 2025. © Armin Linke. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld.

The media has made matters worse, which is why I must be careful in how I phrase this. I do not agree with the likes of Dean Kissick, Jason Farago, and Cornelius Tittel, conservative critics who have variously identified moralism, identity politics, cultural regression, and academicism as the specters corrupting the biennales of our age. Insofar as these developments are not unique to biennales – moralism, identity, regression, and academicism are a reflection of our societies – it would be absurd to divorce a major art show from the same world that produced it. Instead, the issue with our biennales is identical to the problems of our culture: the number of atomized micro-publics that violently jostle for competition in whatever’s left of a public sphere.

In Germany, the situation is still more acute. At the latest with the eruption of antisemitism charges brought against the curators of documenta fifteen (2022), a conservative media sphere declared war on the internationalist ambitions of large biennales. The last thing Germany’s beleaguered politicians – and the cultural arms of those legacy corporations that partly fund them – need is public scandal at their feet. Instead of being the models of fortitude we need, German cultural institutions – unless they try very, very hard not to be – have come to seem like de facto enforcers of silence. No wonder the people do not show up.

Accountability, responsibility, and quality-control do not equal censorship: In fact, they enable us to parse the worthwhile from the worthless.

Enter “passing the fugitive on,” this year’s Berlin Biennale. For this 13th edition, curator Zasha Colah sought to devise an exhibition that would confront, one hoped, the very circumstances I have just described. She writes about “artistic strategies for articulating oneself in difficult or repressive contexts.” In other words, this is a show about protest at the margins, about working within the mess, like foxes coming out at night (to borrow the show’s own visual identity). In practice, the artists in the show have made mostly sculpture and installation – many of the 170 works are new commissions – about war in Myanmar and strife in India; links are made between state violence in Cuba and the disappeared of Argentina. Colah writes of the “the cultural ability of art to set its own laws in the face of lawful violence.” Two thumbs up to all that.

Yet, seeing the show, one is confronted with another kind of fugitivity: escapism and avoidance. Never mind that, ahead of the opening days, no artist list was released. Public messaging around the exhibition was absent to such a degree that you had to wonder whether it was laziness, mismanagement, or a response to some internal crisis. Word on the street is that the organization feared having artists come under attack by a vicious local media all too eager to identify supporters of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement (BDS) – in short, they wished to avoid another documenta fifteen. Whatever the causes, you leave feeling that you don’t have the full story: The works operate almost euphemistically. It’s extremely jarring, for example, to see dunce caps made out of Arabic-language newspapers – Huda Lutfi’s works made over a decade ago, in the wake of the Arab Spring – without considering what has become of the region of late. The works are so removed from their own political moment, and ours, that you wonder what they are doing in this show at all.

Textiles: Zamthingla Ruivah Shimray, Luingamla Kashan, 1990 and 2025 © Zamthingla Ruivah Shimray; Drawings: Larissa Araz, And through those hills and plains by most forgot, And by these eyes not seen, for evermore, 2025 © Larissa Araz; Gabriel Alarcón, Las montañas saben lo que hicieron (The mountains know what they did), 2025 © Gabriel Alarcón. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, 2025. Photo Eberle & Eisfeld

Front (from left to right): Jane Jin Kaisen, Knots and Folds, 2025; Wreckage, 2024; Core, 2024. © Jane Jin Kaisen/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025; Back: Zamthingla Ruivah Shimray, Luingamla Kashan, 1990 and 2025. © Zamthingla Ruivah Shimray. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, 2025. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

There is a sense of disingenuousness that runs through this entire Biennale. Consider the catalogue’s opening pages. There, two representatives from the German Federal Cultural Foundation (who partly fund the Biennale) remark on the gravity of our global turmoil. They single out not Gaza – the calamity that has the same era-defining position in the public consciousness of our age that Vietnam held just over half a century ago – but (wait for it) our “hellish ecocide.” Not Rafah, folks, but the trees. It is a verbal smokescreen almost worthy of writer Victor Klemperer’s compendium of totalitarian doublespeak. They say they are addressing politics; yet, actually, they are not talking about it at all.

Why all this scene-setting? Because that accounts for the strange omnipresence of art here dealing with the civil war in Myanmar, which emerges as the exhibition’s unifying thread. Obviously, consciousness-raising about the plight of the Burmese people – their longstanding ethnic conflict, a 2021 military coup, and the genocide of the Rohingya – is important. The argument might even be made that the crisis there crystallizes numerous repressive currents in the contemporary world. It seems reasonable, then, at the KW, to see a filmed reenactment of an action originally done by a Burmese former political prisoner, Htein Lin, while he was incarcerated. The performance involved him convulsing, strapped in a chair, and finally swallowing a fly. At the back of KW, a ditch in the ground has been dug up by Nge Nom (working with atelier le balto), who was born in 1990. Nom, we read, launched a Civil Disobedience Movement and was chased down by military vehicles before she was taken in by neighbors. It’s a horrific tale, and a meaningful example of fugitivity and survival. It could have been worthwhile to see an entire room devoted to this person’s art and life and the movement she launched.

From left to right: Sarnath Banerjee, Critical Imagination Deficit 2025. © Sarnath Banerjee; Huda Lutfi, The Fool’s Journal, 2013/14. © Huda Lutfi; Gypsum Gallery, Cairo; The Third Line Gallery, Dubai. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. Photo: Diana Pfammatter, Eike Walkenhorst

Nge Nom, The Ditch, 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Nge Nom. Photo: Eike Walkenhorst

If some argument was to be developed about global silence in the wake of genocide, then I’m all ears. Instead, there is just a modest-size hole dug in the ground that, on its own, doesn’t expand upon, challenge, or open up the information we get from the wall text. I want to be moved by all this. I would like to be outraged. I want to feel these individuals’ courage in the face of oppression. But the nature of this oppression is never made clear, nor do such works give me a genuine sense of who these people are, what they fought against, or what they stood for. I am left cold. To be precise: The issue here is not art-as-politics, nor moralism, nor identitarianism. The issue is much simpler: An institution needs to give an audience the resources to make up their minds about what they are seeing. At the very least, just give the work some space.

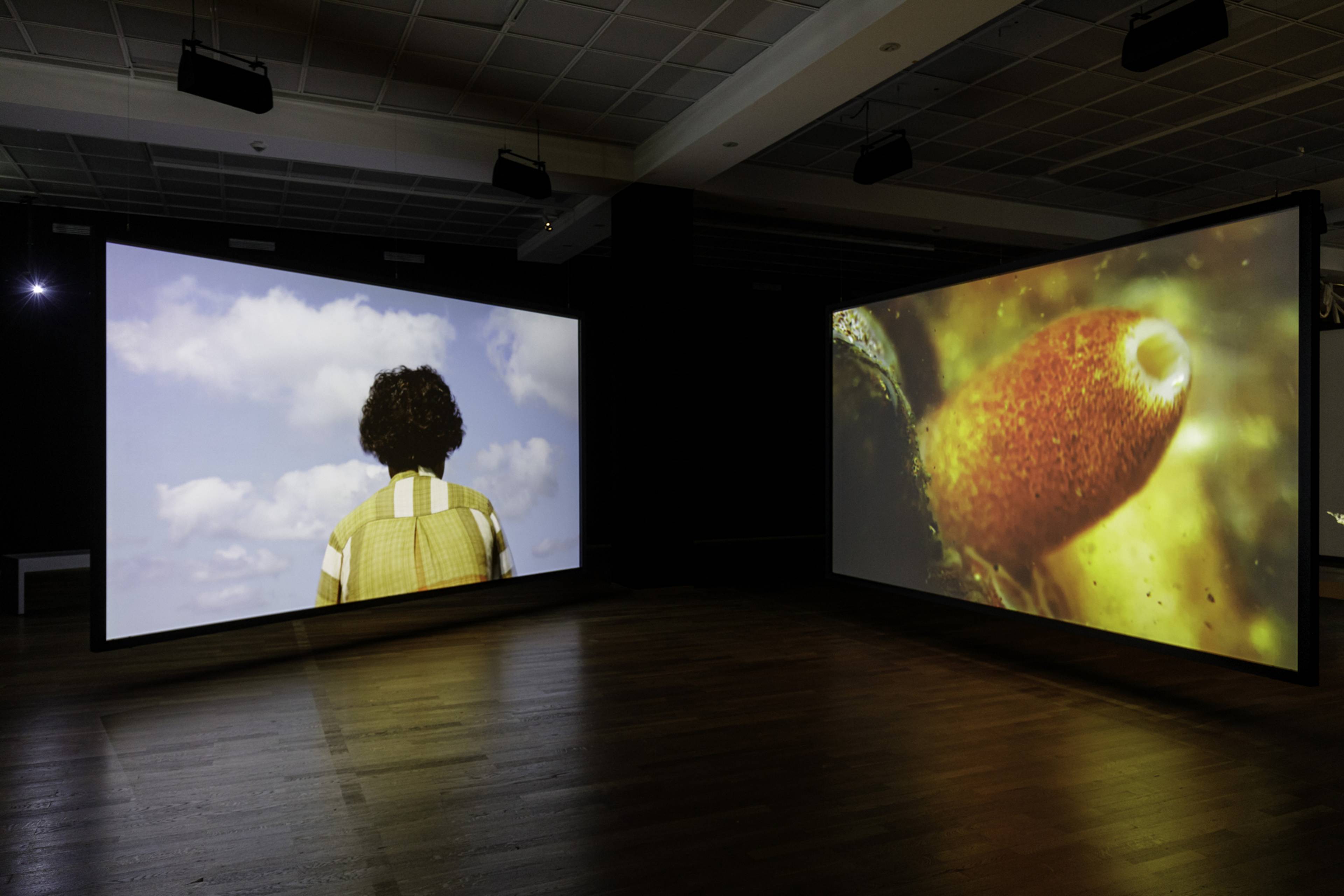

There are brief moments of beauty and dignity in this Biennale. At the former Lehrter Straße courthouse, there’s Fredj Moussa’s لاد البربر [Land of Barbar] (2025), a lush, tender, and humorous 16mm reimagining of a sequence of The Decameron (Giovanni Boccaccio, c.1348–53) set in Tunisia. Over at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Jane Jin Kaisen’s gorgeous four videos portray intergenerational camaraderie among female haenyeo sea divers from South Korea’s Jeju island – perhaps the one suite of works worth seeking out.

Fredj Moussa, لاد البربر [Land of Barbar], 2025, video stills. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025

Jane Jin Kaisen, Halmang, 2023 (left); Portal, 2024 (right). Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, 2025. © Jane Jin Kaisen/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

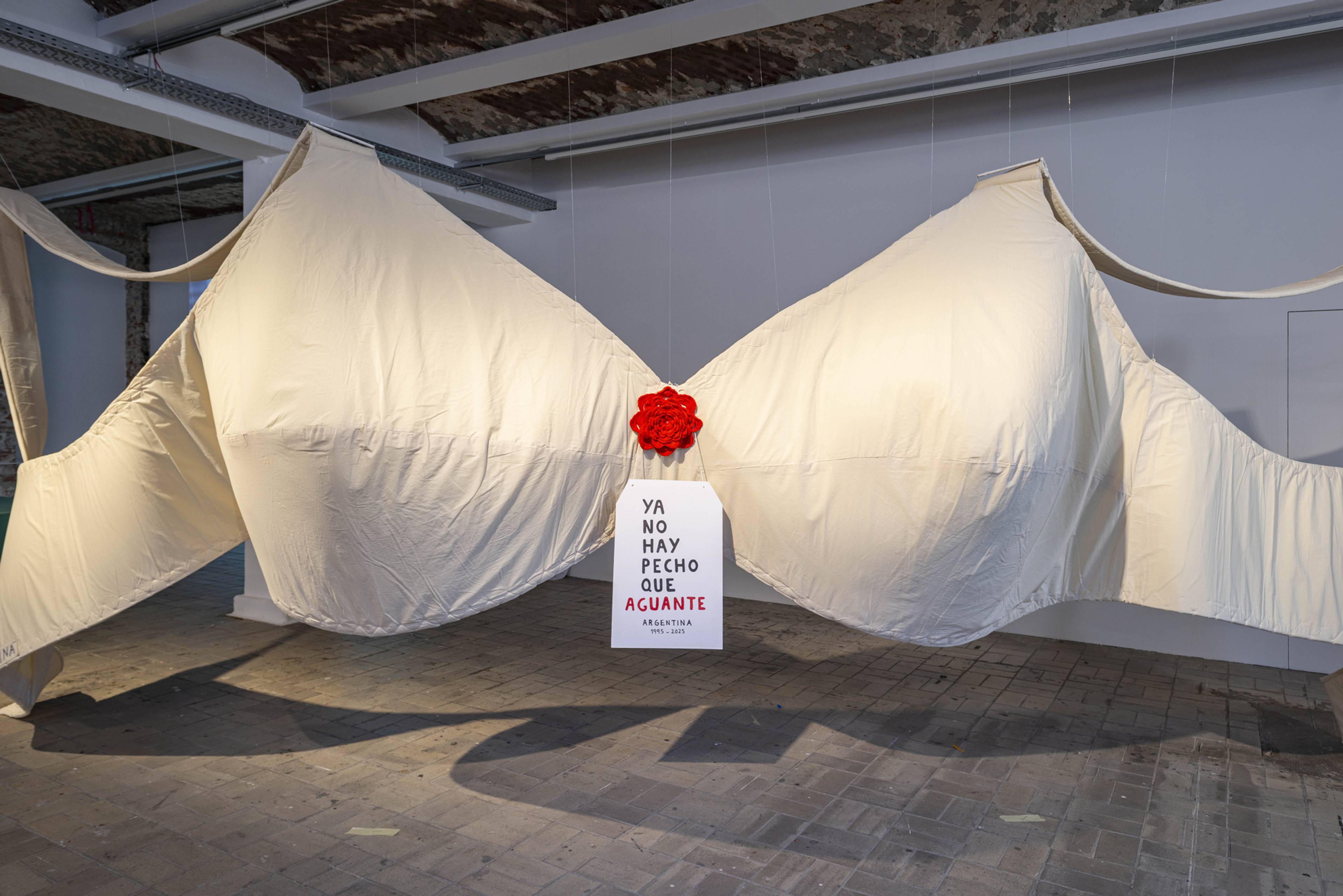

Elsewhere, there is a mishmash of global turmoil. There’s an installation relating to a mail action called Panties for Peace, which targeted leaders in Myanmar after the 2007 Saffron revolution. Vikrant Bhise’s great mural We Who Could Not Drink (2025) links access to water with caste discrimination. Not to mention a room-spanning bra installation by Las Chicas del Chancho y el Corpiño. I could go on.

A few of these contributions, such as those by Moussa, Kaisen, and Bhise, are indeed worthwhile. They deserve to be showcased with space, care, and forethought. With focus, commitment, and argument. They deal with awfully complex issues that each require a great deal of unpacking. But seeing them displayed, sampler-size, in a way that borders on recklessness, does not do them any service. To the viewer, it feels a bit like channel-flipping on international satellite radio: brief flashes of meaning, flashes of horror or heroism or pain. But you never get any dialogical insight that comes from experiencing how such works deal with the realities at hand. Aesthetic experience is superseded by topical immediacy. You come to feel sorry for these artists, their work displayed in such a haphazard mélange.

Instead of being the models of fortitude we need, German cultural institutions – unless they try very, very hard not to be – have come to seem like de facto enforcers of silence. No wonder the people do not show up.

Now, it would be easy to blame sloppy curation. But I don’t believe this was the real issue. The organizers and curators of the Biennale are intelligent and reasonable people. The situation is deeper and more complex than that. Whatever went wrong here follows systemically from the German polycrisis.

In our age, and particularly in today’s Germany, the rhetoric of crisis management has infected organizational thinking. A crisis exists even if it proceeds only in counterfactuals; each potential ship-sinker must be thought through to the end, even if it does not yet exist. What if an artist gets cancelled? Likes a BDS-friendly Instagram post? Shouts “Free Palestine” somewhere in public? Makes a work that will upset the funders? These are the fears that occupy the heads of the organizers. How easily such fears are passed down to the public.

Vikrant Bhise, We Who Could Not Drink, 2025 © Vikrant Bhise; Experimenter, Kolkata & Mumbai

I have no inside information that any such incidents happened. But let’s assume, solely for the sake of argument, that something went wrong. How would you, as an organization, react? Naturally, you would minimize the risk of damage. Externally, you would proceed as though everything were normal: launching a website, organizing curatorial workshops, mediation groups, and tours. But internally, your real efforts would lie not in selecting the best art you could, but in minimizing the risk of damage. You avoid challenging topics. You don’t release an artist list. You speak of ecocide and not genocide. You display a work about the Arab Spring in 2025. Myanmar emerges as a convenient topic. Soon, you have your political show that pleased the organization, but alienated everyone who stepped in that exhibition. Crisis averted.

Biennales, again, reflect their cultural moment. I don’t know what real issues this Biennale faced – the claim that funding was massively reduced seems somewhat exaggerated – but I do know that getting anything done in Berlin in 2025 means dealing with this same sclerosis of crisis management and the inflexibility this produces. Fact: Key government agencies communicated with one another by fax (yes) during the pandemic. Fact: Data protection regulation makes it impossible to reach the people you need to reach. Fact: Filling out applications “digitally” means downloading a PDF and printing it out – then running to the post office to snail mail it. I do not envy the people who put together any biennale in Berlin. They must face the failed story that is this city.

Kikí Roca, Las Chicas del Chancho y el Corpiño, El Corpiño (The Bra), 1995/2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Kikí Roca, Las Chicas del Chancho y el Corpiño. Photo: Marvin Systermans

Piero Gilardi, Drago bce [Dragon of the ECB], 2012. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Fondazione Centro Studi Piero Gilardi. Photo: Diana Pfammatter, Eike Walkenhorst

The result is an institutional accessibility and lack of quality that – in the best case – might be disingenuously played off as “artistic freedom.” (It’s an argument I’ve heard before: “It wasn’t us; it’s what the artists wanted to do.”) But institutional laziness is not the same as artistic liberty. Managerial baton-passing is not identical to freedom of speech. Accountability, responsibility, and quality-control do not equal censorship: In fact, they enable us to parse the worthwhile from the worthless. In the early days of reunified Berlin, it may have seemed quaint to encounter bureaucratic friction and retrograde motion amid a world blissfully going in the wrong direction. But now, the city’s rough-at-the-edges mentality is not an aesthetic of freedom, but of dysfunction and stagnation. At some point, it’s just not cute. Institutional crisis-aversion is certainly not what I want to spend my afternoon thinking about. It’s not why anyone visits an exhibition, either.

What will become of the Berlin Biennale? Will it go the efficient American direction in its next edition, like Documenta? Whatever happens, someone, somewhere, needs to take a step back and remember the basic remit of exhibition-making: to show things that someone will want to see. Because ignoring a show’s most essential purpose – to exhibit something that deserves to be seen – was the colossal disappointment of this failed biennale.

Busui Ajaw, from the series “The Military State’s Oppression of the Peoples,” 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Busui Ajaw. Photo: Marvin Systermans

Helena Uambembe, How To Make a Mud Cake, 2021/2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Helena Uambembe. Photo: Raisa Galofre

, Ouma’s !Hàna̋s: Of Wor(l)ds Turned to Dust. Prossession Peda’Gogo and Yvette Abrahams Reading Cycle, 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Memory Biwa. Photo: Marvin Systermans

Milica Tomić, Is There Anything in This World You Would Be Ready to Give Your Life For?, 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Milica Tomić; Charim Galerie, Vienna; Grupa Spomenik Archive, Vienna; Marija Milutinović Archive. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

Isaac Kalambata, Bamucapi (Witchfinders), 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Isaac Kalambata. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

Gernot Wieland, Family Constellation with a Fox, 2025. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld

Judith Blum Reddy, I’m Afraid of Americans, 2018. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Judith Blum Reddy. Photo: Marvin Systermans

Front (column): Tsuyoshi Ozawa with Andreas Eberlein, Dagmar Tinschmann, Daisuke Deguchi, Jinran Kim, Kathrin Schiff bauer, Li Koelan, Manuela Warstat, Yuan Shun, New Nasubi Gallery, 1993. © Tsuyoshi Ozawa, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025 for Dagmar Tinschmann-Lichtefeld, Kathrin Schiffbauer, Manuela Warstat and Yuan Shun; Back (videos and installation): Etcétera, LIBERATE MARS, 2025. © Etcétera. Installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. Photo: Diana Pfammatter, Eike Walkenhorst

___

13th Berlin Biennale

“passing the fugitive on”

KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Sophiensæle

Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart

Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße

14 Jun – 14 Sep 2025

![Fredj Moussa, لاد البربر [Land of Barbar], 2025](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/syotmk9q/production/710603f6ef9f160004227e72b83c98f1a15c7dbb-2000x1352.jpg?w=3840&q=70&fit=clip&auto=format)

![Piero Gilardi, Drago bce [Dragon of the ECB], 2012](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/syotmk9q/production/bd4873d34740a154336745c8368e58067bf47507-2000x1334.jpg?w=3840&q=70&fit=clip&auto=format)