Filmmaking is a narrative art at architectonic scale. Meaning, that it often leads to wonderfully awkward instances in which one person’s most private, oneiric visions must be translated into gruff orders for a vast team of specialists with only a purely instrumental sense of the project. Dreams become clockwork in the studio system. Only fitting, then, that many of cinema’s most iconic projects have left behind notes that resemble modern hieroglyphics, in which affectingly ambiguous moments were broken down into shot lists and lighting cues via industrial shorthand.

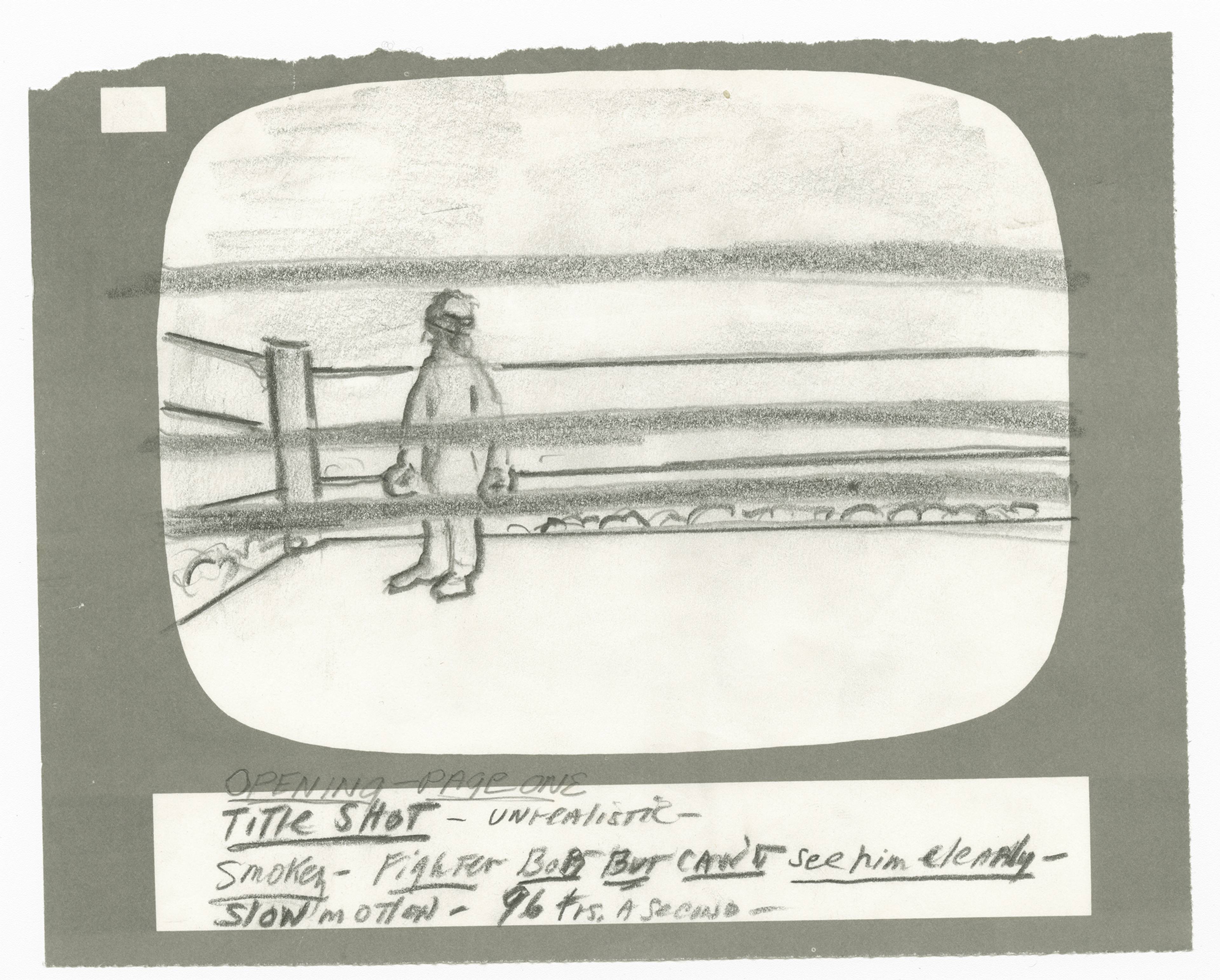

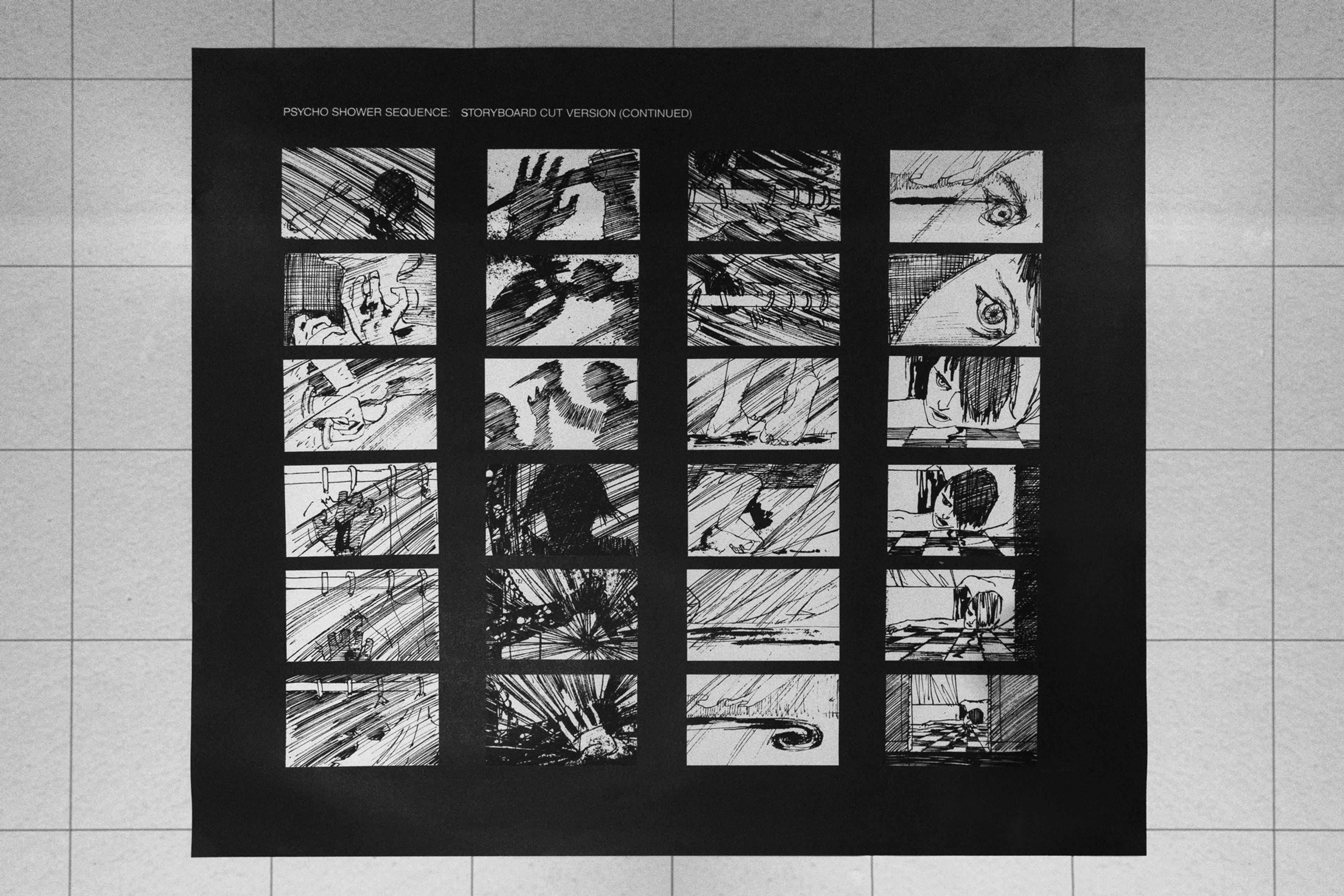

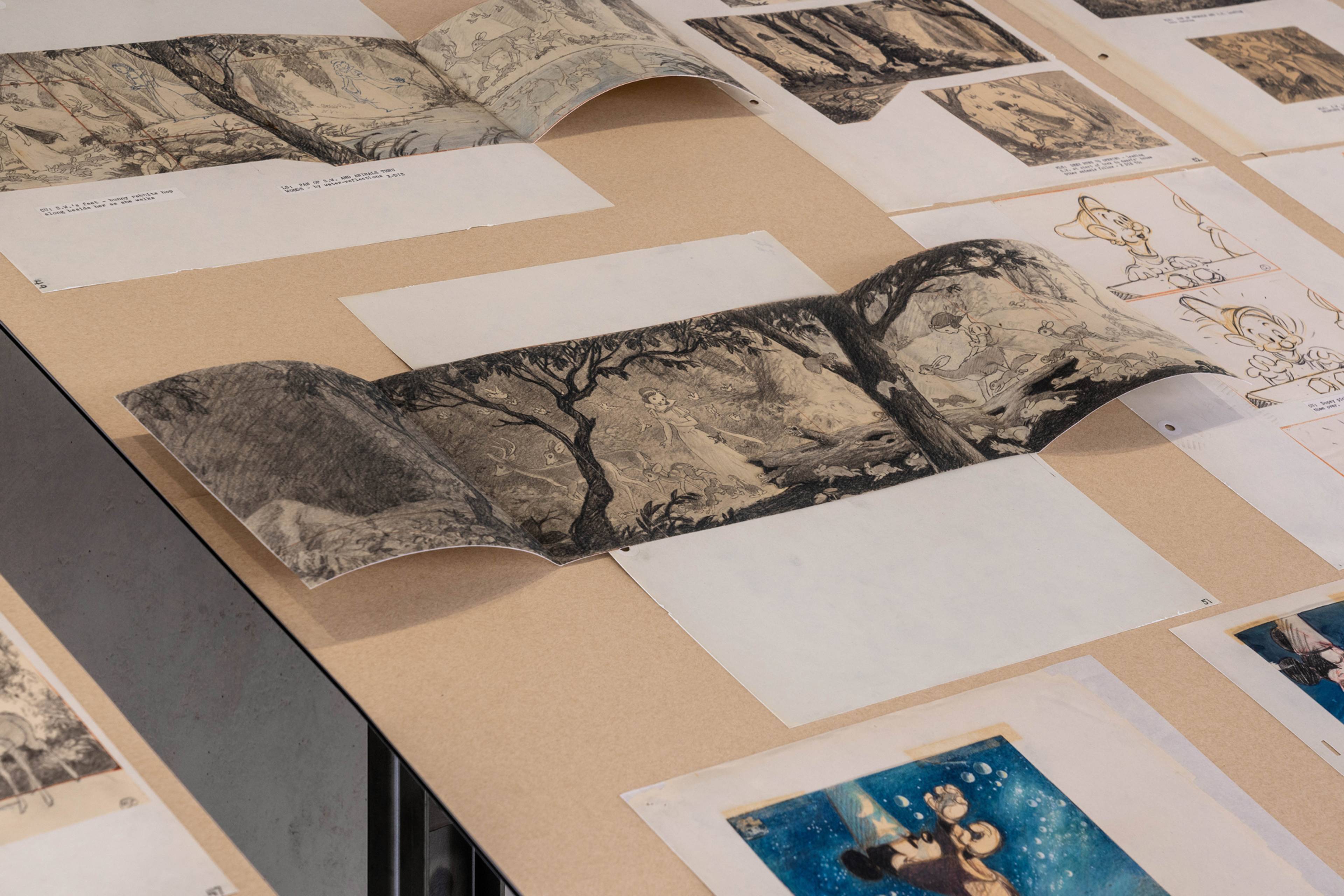

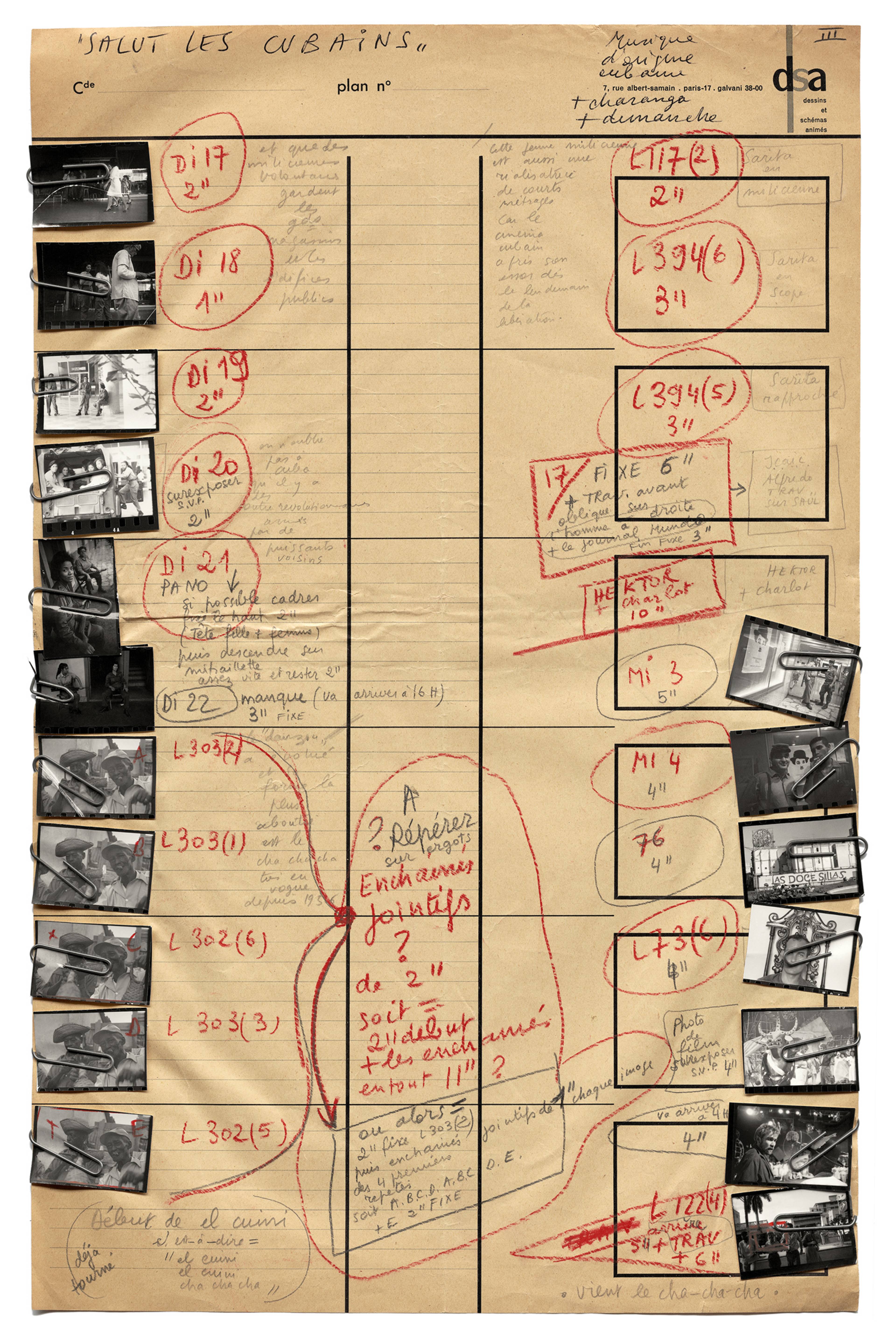

Curated by Melissa Harris, former editor of Aperture photo magazine, this show represents the largest exhibition of these hermetic drawings ever assembled, combining production notes for over fifty films spanning almost a century. Art-department sketches for the imperial palace in Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and mock-ups for the shower scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) brush edges with drawings by Federico Fellini and Satyajit Ray and scouted location photography by Wim Wenders and Agnès Varda. Combined with favors only the Fondazione could call in (“Madame Prada is a great fan of cinema,” I was told several times), the scope of Harris’s efforts are impressive. And yet, the films that these scribbles and snapshots eventually produced are notably absent from the show, giving the exhibition a somewhat forensic air, as though one is reconstructing the final days of a vanished glamor queen.

The Great Dictator, directed by Charlie Chaplin, 1940. Storyboard by J. Russell Spencer, 1940. © Roy Export Company Ltd.

Psycho, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, 1960. Storyboard by Saul Bass, 1960.

Exhibition copy. Courtesy: Saul Bass papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences

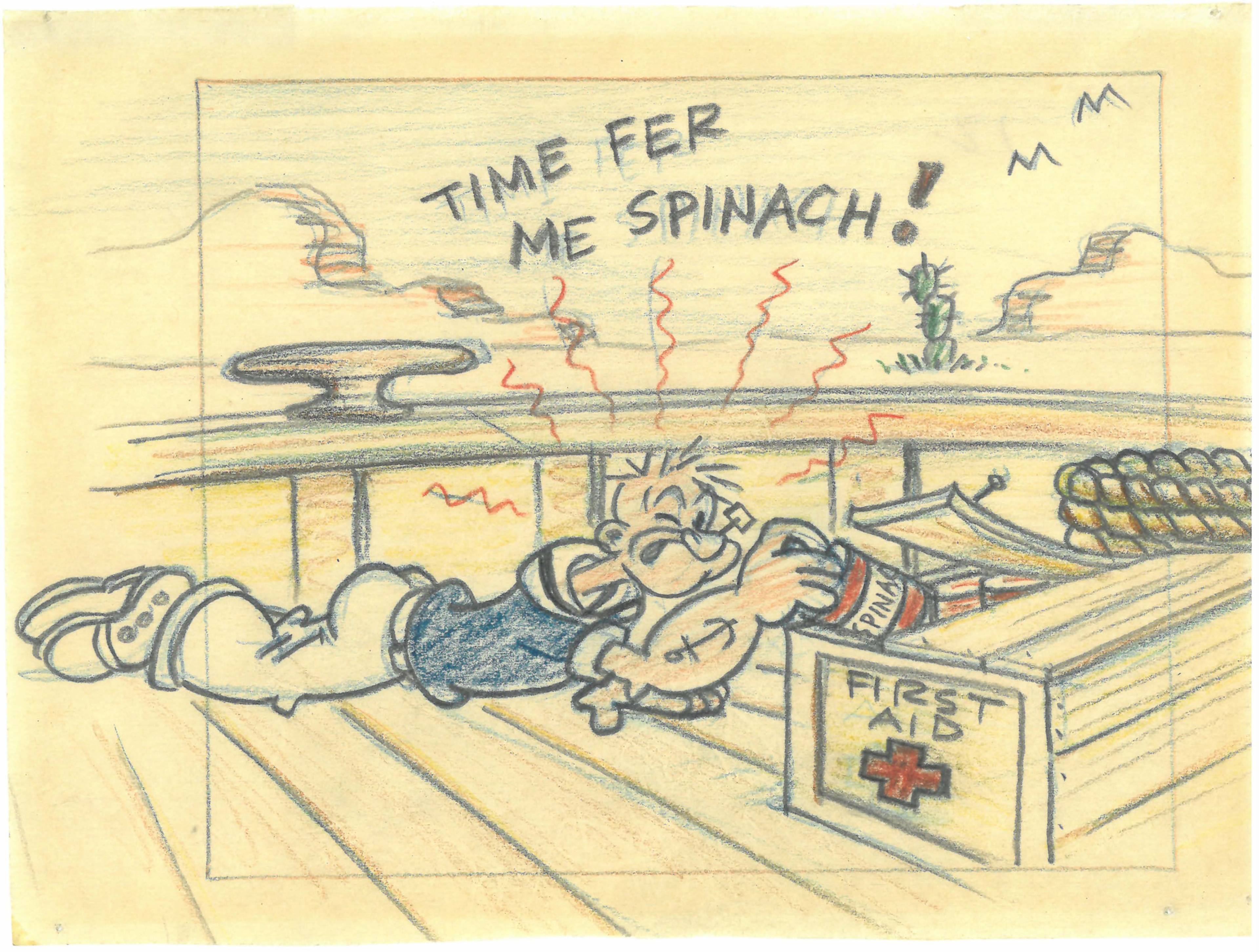

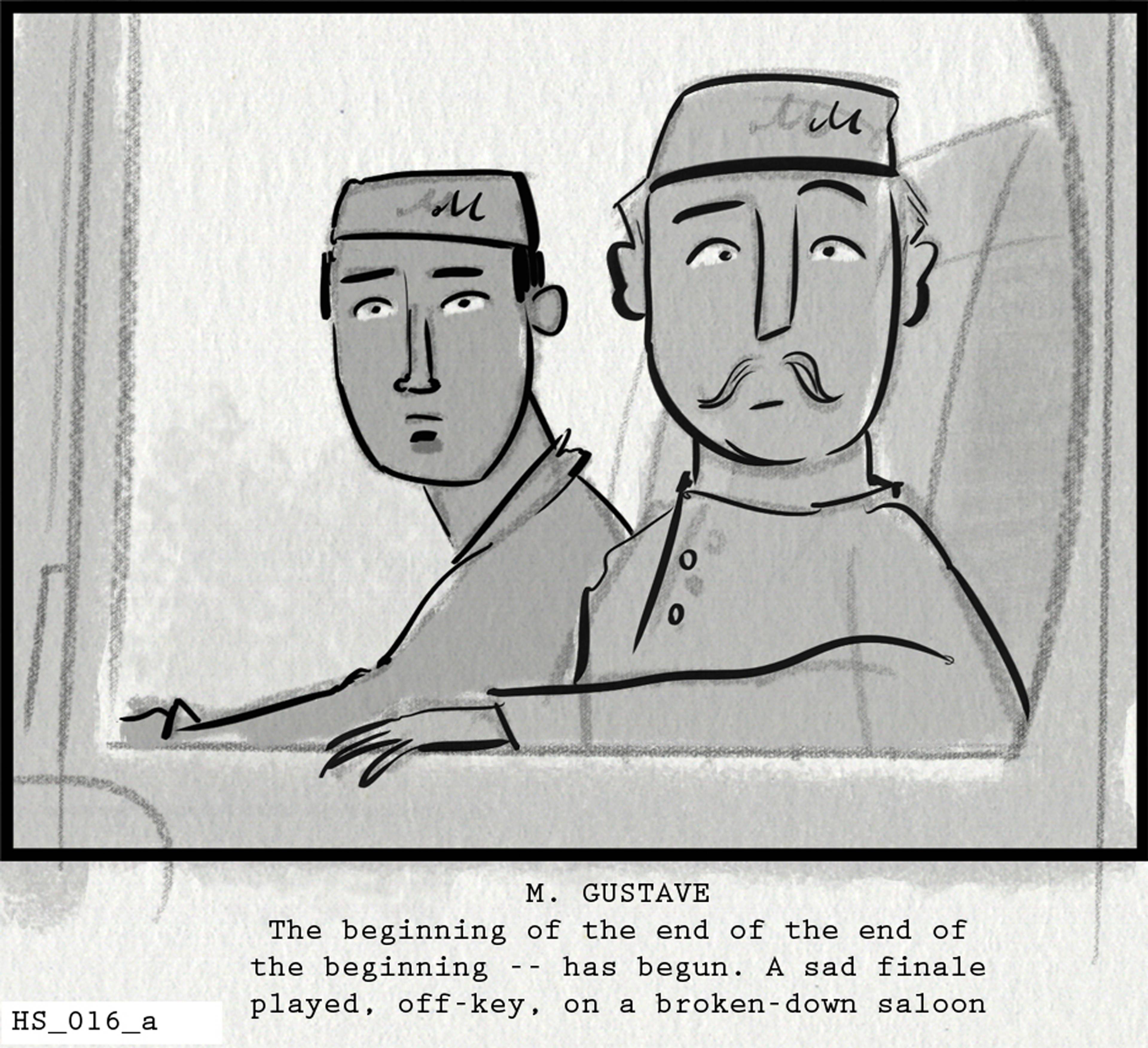

Apart from several very fine renderings for animations by Walt Disney Productions, Fleischer Studios, and Hayao Miyazaki, aesthetic pleasures feel accidental here. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s sketches for Mamma Roma (1962) look like they were drawn on the dashboard of a car bumping along the Appian Way. Sofia Coppola’s hand-drawn storyboards for The Virgin Suicides (1999) carry a bit of the director’s disheveled charm – she evokes Lux Lisbon’s subtle pout with just a few strokes of blue ballpoint – but my eyes kept wandering over to a nearby script page, where crossed-out lines and margin notes spoke of more decisive action. Even Wes Anderson’s renderings for The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), one of the most sumptuously decorative films of this century, consist of animated line-drawings bobbing stiffly on an iPad. Anderson himself narrates all characters. As a glimpse beneath the layers of an exquisitely dense creative practice, it’s interesting, if only for revealing that a stage of crude utility exists in his productions at all.

View of “A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema,” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan. Courtesy: Fondazione Prada. Photo: Piercarlo Quecchia – DSL Studio

Popeye the Sailor, storyboard original art sequence by Fleischer Studios’ eight staff animators, c. 1940s–50s. © The Mark and Susan Fliescher Collection

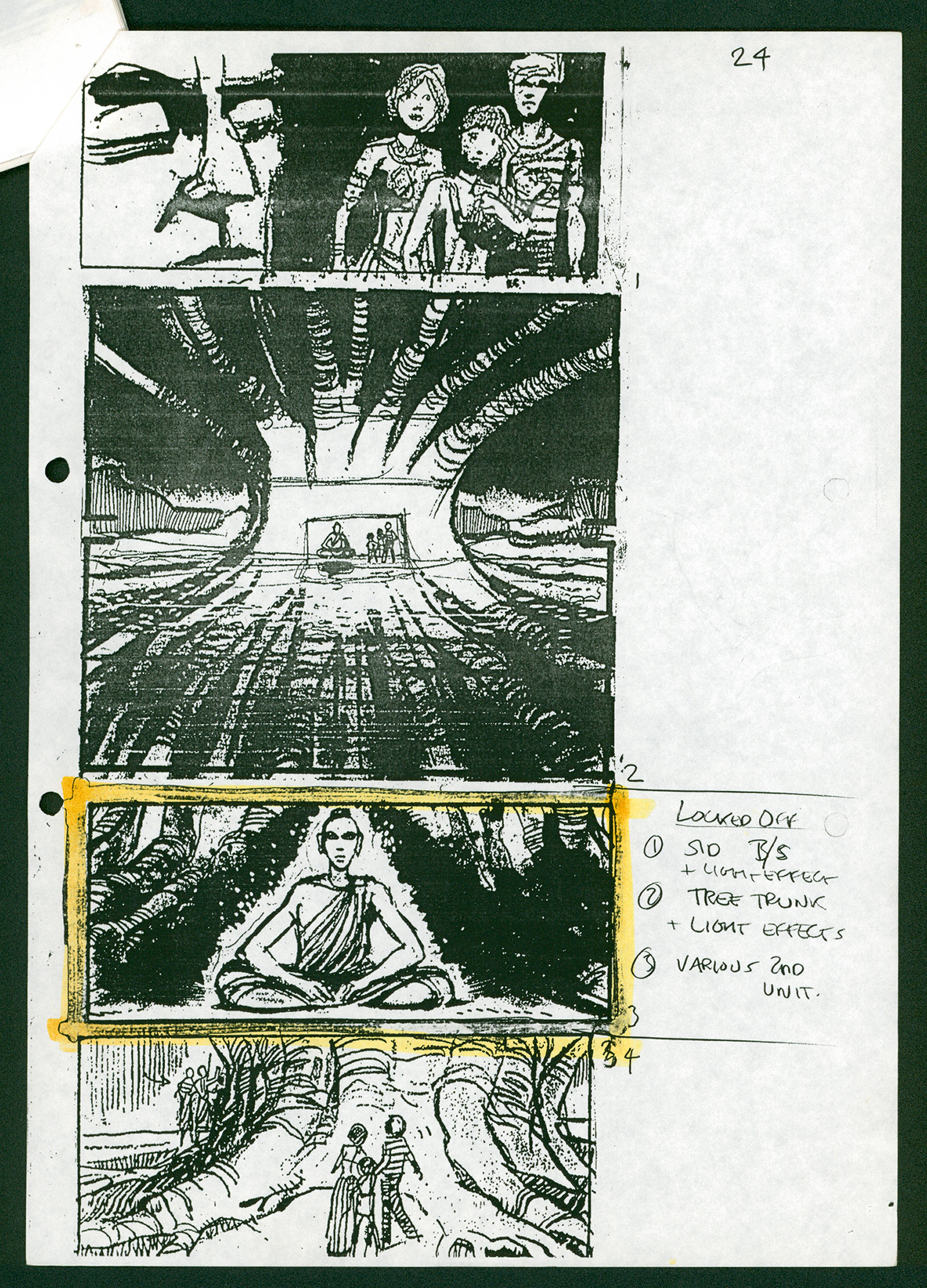

“A Kind of Language” is inclusive almost to the point of meaninglessness, with “Other Renderings for Cinema” stretched to fit ephemera from a Carrie Mae Weems video installation and Jia Zhangke’s editing suite. But, with patience and a generous frame of mind, it’s possible to divine from this show not only the secrets of many individual productions, but the story of cinema itself over the 20th century. Hand-drawn sketches by Todd Haynes and Martin Scorsese may move us as testaments to these directors’ “authorship” of their films, but, as a rule, storyboards are cleanest as drawings and clearest as production notes when they were made far away from the director, by an art-department hand on a studio salary. In the margins of an elaborately shaded drawing of Manderley manor from Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), an anonymous lackey casually spitballs ideas for the opening sequence to mega-producer David O. Selznick (whom, it should be noted, is addressed as the movie’s primary architect). This is in marked contrast to the tone of forced cheer in notes for Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha (1993), where production designer James Acheson couches bad news of further delays to the director within a promise of new special effects techniques that he hopes “will be music too [sic] the producers’ ears.”

Little Buddha, directed by Bernando Bertolucci, 1993. Storyboards, 1992. © Bernardo Bertolucci Foundation and Recorded Picture Company

Salut les Cubains, directed by Agnès Varda, 1963. Storyboard by Agnès Varda, 1962. © Agnès Varda Estate

As Hollywood morphed into a director-driven enterprise around the 1960s, with risk-averse producers stepping back into private-equity roles, the business model became more ergonomic, gradually replacing collective manpower with technology and monomania. Anderson’s elaborately self-composed productions are the direct result of this new austerity principle: baroque DIY. Whether this is good or bad for cinema is an open question. But it’s plainly bad for storyboarding, along with any other production task requiring many hands and many minds. Last year, following strikes by the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild that won protections against AI, the Art Directors Guild notably failed to secure the same, enabling studios to continue reducing skilled labor to rote machine functions.

Despite its lack of direction and overall thesis, “A Kind of Language” takes storyboarding seriously as a form of communication, one developed in the microcosm of collaborative design. This sort of collective creation is endangered today, and documents such as the ones shown here are beginning to look ever more runic and arcane. “A Kind of Language” makes no claim for its own historicity, but it may well be the first memorial for a dying art form.

The Grand Budapest Hotel, directed by Wes Anderson, 2014. Storyboard by Jay Clarke. © Searchlight Pictures. Courtesy: Wes Anderson

___

“A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings For Cinema”

Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan

30 Jan – 8 Sep 2025