One of the stickiest formulations from reading Immanuel Kant is “form of purposiveness without a purpose,” which, per the philosopher, might characterize the beautiful. While I doubt that it could be used to define art, as some people have put forward, the term perfectly describes my experience of specific artworks: namely, those that look like machines, but lack a (practical) purpose. So, it is perhaps not surprising that the expression kept coming back to me during a walk through Albertina Modern, where a joint exhibition combines many drawings and five sculptures by Bruno Gironcoli (1936–2010) with sculptures by the Vienna-based artist Toni Schmale (*1980). The starting point for this exhibition was a cycle of 155 drawings by Gironcoli donated by Agnes Essl, whose joint collection with her husband constitutes the backbone of the museum, opened in 2020 as an Albertina extension dedicated to contemporary art.

Views of Bruno Gironcoli – Toni Schmale, Albertina Modern, Vienna, 2024. Both © Rainer Iglar

Despite the joyfulness of certain drawings and the sculptures’ subtle playfulness, the exhibition is fairly orthodox, to the point of appearing austere. I mostly engaged with Schmale, whose works have puzzled me for a while. Within a refurbished 19th-century historicist building, the choice of display classicized her works, which would have felt more at home in a post-industrial architecture like Tate’s Turbine Hall. The lists of her materials and processes reflect this proximity. Take “steel, sandblasted, black-finished, oiled with Castrol WX-30” for fury (2019); “powder-coated steel in RAL 9005, heat-treated and waxed steel, concrete” for the menacing-looking waltraud (2016); or even “galvanized steel, powder-coated steel (RAL 4007), aluminum, brass, polyurethane (Biresin 450)” for hl. antonia (2015). Such descriptions are commonplaces in factory documents, and might even form an unusual poetics of their own. By contrast, most of Gironcoli’s works are spartanly described as “pencil and colored pencil on paper” (for the drawings) and “aluminum” (for the sculptures); four remaining pieces are simply “mixed media” or “mixed media on paper.”

The industrial precision of Schmale’s lists of materials is no coincidence, of course, but evoke the artist’s very real knowledge of and physical involvement in the works’ production. A wall text hones in on the strenuousness of it all: “standardized steel tubes are bent, stretched, and transformed through the artist’s employing her body to the point of physical exertion.” Thus, the artist’s absent body is very much present, even though its traces remain largely invisible to an untrained eye, which is rather struck by the perfection of Schmale’s forms.

Bruno Gironcoli, Moses verfängt sich im Schilf (Moses Gets Caught

in the Reeds), 1956, aluminium, 55 × 40 × 60 cm. Photo: The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Toni Schmale, dipstation, 2013, sandblasted steel, oiled with Castrol WX-30, concrete, 120 x 50 x 80 cm. © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2024. Courtesy: the artist

More salient was the absence of another body: that which performs or endures actions from, on, or through the sculptures. Some of Schmale’s objects convey possible exercises, others potential violence – and sometimes both at once. The materials and structures resemble sports equipment or machinery and create ambiguous forms, like the exercise bench or the fascia roller. As opposed to works like Gironcoli’s Teller mit Kornähren (Plate with Ears of Grain, 2008) or Moses verfängt sich im Schilf (Moses Gets Caught in the Reeds, 1956), very few of Schmale’s sculptures are representational; even the work dipstation (2017), would hardly function like its non-art correlate, its two “dip bars” installed on different walls. Rather than depictions, Schmale’s works approach simulacra, and finally eschew definitive identification altogether; in other words, they stir the feeling that they have a purpose, but refuse us any conviction as to what they are – beyond aesthetic arousals, that is. In this sense, they might epitomize the Kantian oxymoron, especially because they also make salient what they are not: good for something (specific).

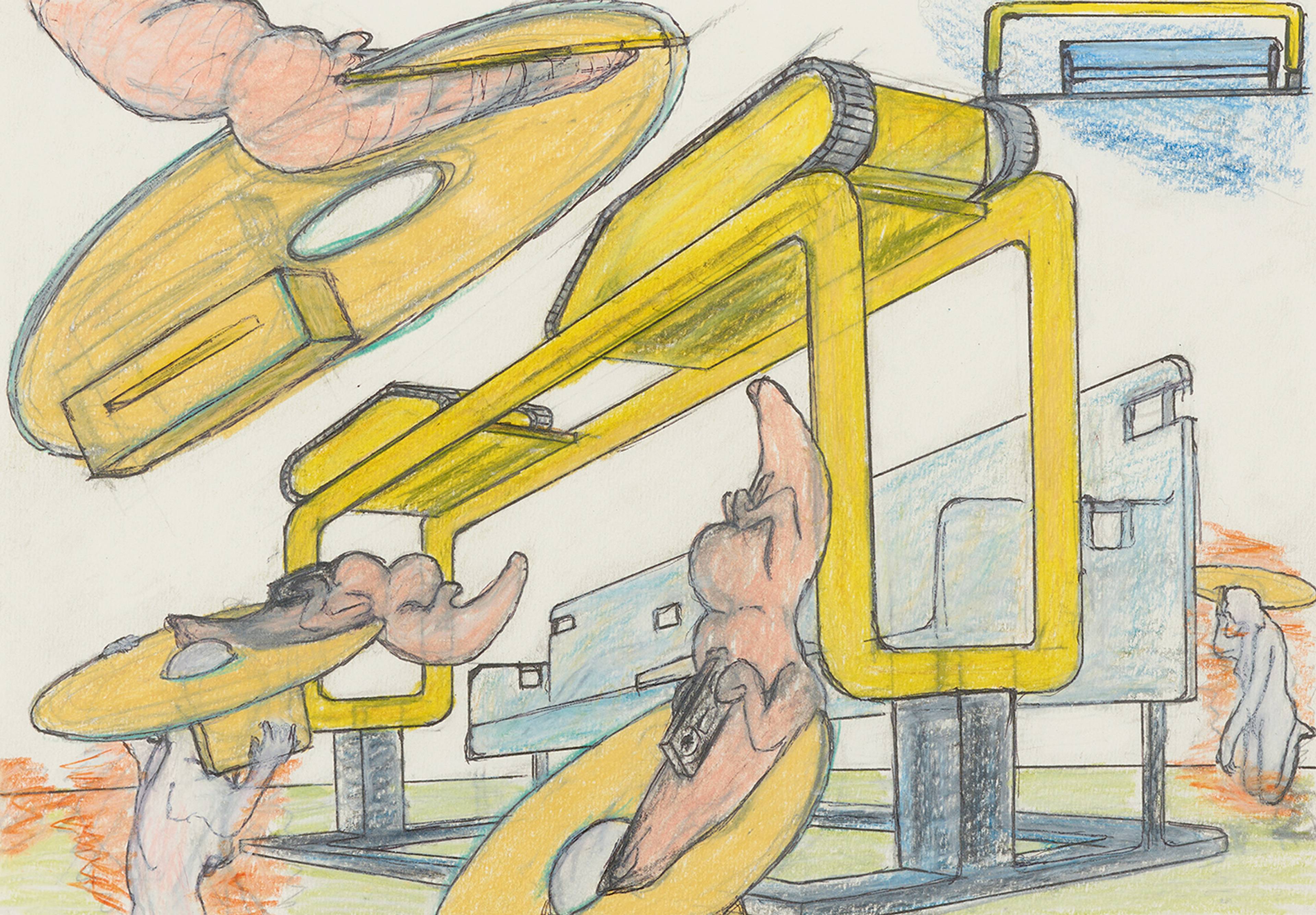

It is precisely this projective activity of the viewer’s imagination that turns Schmale’s sculptures into “machines for thinking.” The large and complex “machines” that human-like characters interact with in Gironcoli’s drawings (and several sculptures) underscore the bodies – and narratives – missing in Schmale. Yet, in Gironcoli, too, the purpose of the machines remains open. His works thus show that narrative and body are not enough to provide purpose. From a purely experiential perspective, the greater openness of Schmale’s contributions worked on me more effectively. They appear as plausible minimalist artifacts that have absorbed an industrial aesthetics and coolly connote contemporary attempts at body transformation in post-industrial societies. As our leisure class drives conspicuously towards self-optimization at the behest of its trainers and our rapid image economy, it is a wry, inventive decision for Schmale to import forms whose looks exhaust the very thing they’re for.

Toni Schmale, lap, 2013, hot-dip galvanized steel, powder-coated steel RAL 8017, concrete, 101 x 66 x 58 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

___

Bruno Gironcoli – Toni Schmale

Albertina Modern, Vienna

3 Apr – 28 Jul 2024