There’s a certain kind of movie that comes around every summer to revive the US-American art houses. It tends to be French, takes place in the summertime, and concerns a bunch of bored, glamorous people as they suntan, have affairs, and occasionally murder each other. Last summer, it was Ira Sachs’s Passages (2023). The year before that, Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969) had its two-week restoration run at New York’s Film Forum extended eight times. These movies are taken seriously by film buffs, and receive a bevy of date-night interest from the majority of people that don’t go to the movies regularly. They’re sensual in ways that are typically kept out of public view. Sometimes, they explore a taboo, and, in their own small way, make a new facet of erotic experience open to collective contemplation.

French director Catherine Breillat uses this genre of arthouse cinema as a trojan horse. Though her movies often involve the same components – sexy French characters with time on their hands – she deploys them to document the alienation and cruelty that fuels sex under patriarchy, and to provoke us to reevaluate our place in its matrix. Many great movies do this (one of them, Chantal Akerman’s 1975 feature Jeanne Dielman, was recently put at the top of Sight and Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time), but no other filmmaker so cunningly plays our own erotic expectations against us. Across her fifty-year career, she has restaged some of patriarchy’s most enduring sexual fantasies from women’s perspectives, centering younger women searching for a sense of self against a backdrop of creepy, pathetic older men.

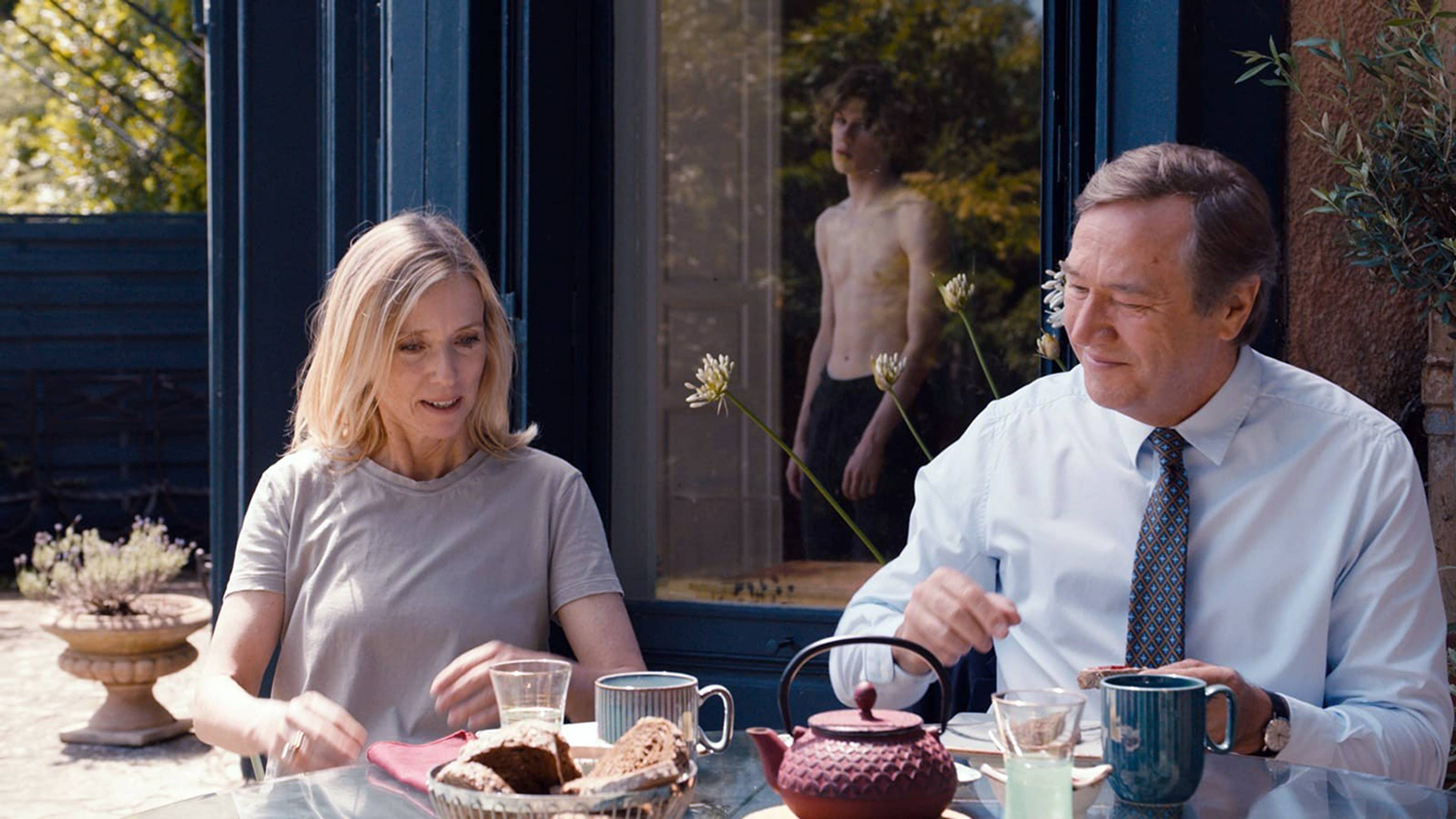

Her latest, Last Summer (2023), is a thrilling and incisive update to her form, flipping the script to put a woman in the role of abuser. A key, early scene captures the film’s laconic vibe, as well as the darkness always lurking beneath the surface of Breillat’s images. On a bright summer’s day on the outskirts of Paris, Anne (Léa Drucker), a successful lawyer, is lying on the lawn of her mansion when her seventeen-year-old stepson, Théo (Samuel Kircher), approaches with a beer and a tape recorder. Bored, he starts peppering her with innocuous questions. Best day of your life? “Adopting the girls,” Anne tells him, referring to her two pre-teen daughters. Worst day of your life? When she found out she couldn’t have children of her own, the result of an abortion she’d had when she was very young. Biggest fear? “That everything will disappear,” Anne answers flatly. “Or, worse, that I will do all I can to make it disappear. It’s my vertigo theory: The desire to fall is really a desire to jump.”

That answer flies right over his tousled head.

“First time with a man?” Théo asks, flashing a pubescent grin. But Anne refuses to answer. Théo doesn’t get why. When he won’t let up, she simply says:

“Some things should never, never have happened.”

“… Like us?” Théo asks. He and Anne, his stepmother, have already slept together once. Inadvertently, he’s drawing a connection between their relationship now and what Anne is refusing to talk about. Anne responds in kind, from the perspective of the manipulator:

“There is no us.”

Last Summer slipped into theaters right around the start of sexy French movie season. On its poster, Drucker and Kircher smile seductively at each other, her arms around him, while they share an electric scooter. I sometimes wonder about the people who came to see it off the street – perhaps on a second or third date – and how the rest of their nights went. Though saturated in sunlight, sunglasses, and designer handbags, Last Summer is uncomfortable and deeply depressing. I left the theater devastated by my first watch. When I saw it again, knowing the outcome in advance, it took on the proportions of Oedipus Rex – an unstoppable tragedy that’s also just wrong.

If you think an older woman taking advantage of a younger man has nothing to do with patriarchy, consider mainstream porn. According to the Daily Beast, scenarios involving a storyline about a stepparent or stepsibling, known as “fauxcest,” now account for over half of top-viewed videos on aggregators like Pornhub. Political theorist Alex Lefebvre proposes that these videos don’t merely involve non-blood relatives to unsubtly tap an incest taboo; rather, they make use of the singular dynamic between stepparent and stepchild (or its popular misconception) to smuggle in the erotic element of pity. In this telling, the scenario revolves around an older woman’s effort to win the approval of a pathetic, antisocial younger man: “The same stock character, he is almost always white, bored, or bummed out, watching TV, playing video games, or on his phone,” Lefebvre notes. “The attraction is not that she is related to him by ties of marriage. It is that she is there, in the same time and space, and he doesn’t have to go out into the world. He doesn’t love her; he doesn’t even like her. She’s simply something to do, a surface to cum on, and best of all, he doesn’t have to change out of his sweatpants.” This is the (often literal) perspective that many men, knowingly or not, seek out in sexual fantasy.

Last Summer’s Théo is a version of Lefebvre’s antihero. His parents divorced when he was young, and his corporate-executive father, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), was largely absent from his upbringing. When his biological mom sends him to Anne and Pierre’s for the summer, he spends the first days of his vacation smoking on the patio, watching videos on his phone, and leaving wet towels all over the house. Though he is sexually active (in an early scene, Anne catches him sneaking a girl his age up to his room), he resembles the nebbish, incel-adjacent character in so much of today’s mainstream porn.

In an age when feminism has been co-opted by entrepreneurship and pop psychology dares to dream of a post-historical politics for sex, Breillat’s work proves that deeply fucked-up dynamics still stalk our psyches.

But Breillat isn’t interested in Theo’s perspective; instead, she refreshingly reconsiders this dynamic to make legible a very different set of desires. Why would a successful woman, happily married to someone her own age, do something like this? What could she possibly get out of it? In Anne’s case, their amity begins when she finds proof that Théo was responsible for a break-in that occurred just after he arrived in Anne’s home. She offers not to tell his father, to keep it their little secret, if he promises to make an effort to “be part of the family.” In contrast to the usual coercive negotiation that initiates most stepcest porn, it seems as though Anne’s initial intent truly is innocent. She just wants Théo to try a little harder.

From this moment on, Breillat directs their dynamic with remarkable ambiguity. As far as I can tell, Théo never expresses an interest in or attraction to Anne, and we get nothing so obvious as a moment of her ogling him. Rather, Breillat’s decisive cuts suggest that their game of seduction is actually one Anne is playing against herself, drawn in by the very possibility of losing control. Before they even sleep together, she allows Théo to give her a small tattoo on her elbow. Brilliantly introducing touch into their relationship, it’s more important yet as a moment where Anne clearly crosses one of her own lines. This transgression is not about Théo – he’s just the instrument allowing her to indulge. She crosses another line in Théo’s bed, when Anne comes in to tell him to turn the lights out. It’s arrestingly unclear who makes the first move.

After he and Anne sleep together, Théo behaves like the teenage boy he is, rubbing against and pinching her whenever possible, including in front of Pierre and the girls. Anne takes him to a shadowy part of the lawn and gives him a firm dressing down, as though it’s up to Théo to stop them before they get caught. When he stomps away, yelling “You’ll be jealous when I start bringing home girls!” the gap in their conceptions of their relationship is appallingly apparent; her power trip is his first brush with love.

When she’s not sleeping with her stepson, Anne’s legal practice specializes in custody battles and the rights of minors – an inconceivable dissonance from her amour fou. But Breillat, whose source material ranges from fairy tales and true crime to events from her own life, is indifferent to psychological realism. Her characters only emote when it’s expected of them, and otherwise seem to pass through life in a stupor. Adapted from the 2019 Danish movie Queen of Hearts, Breillat’s main update in Last Summer was removing anything that might telegraph Anne’s feelings, especially a sense of struggle with her own alienated desires. Looking back at her sunlit conversation with Théo as a psychoanalyst might, it’s possible to infer that Anne’s introduction to sex happened before she was an adult, and was likely traumatic. This is also a red herring: Where movie logic tells us that incriminating evidence of their tryst should come back to haunt Anne, as one piece of epistemological truth she can’t fuck with, she succeeds in stealing the tape recording of their conversation out of Théo’s bedroom the moment she knows she’s in trouble. From then on, it seems as though she gets away with her version of the story, and the film is just long enough for Breillat to suggest what capably living out that kind of lie would mean.

Calling herself “a feminist, but not in my films,” Breillat seems intent on showing sexual relationships built on people’s worst urges, for which she has been scorned in France and generally deprogrammed abroad. The people I know who like her work fall into two overlapping categories. There are the film buffs, who speak about her work as showcases of exquisite technical form – of blocking, framing, lighting, and wardrobe – tonally united by gradations of Breillat’s tar-black humor. Then there are the glamorous, intelligent women who describe her works as radically empowering, lauding the career risks she has taken to make points about patriarchy that are both so obvious and so unspeakable that we rarely see them treated frankly. In an age when feminism has been co-opted by entrepreneurship and pop psychology dares to dream of a post-historical politics for sex, Breillat’s work proves that deeply fucked-up dynamics still stalk our psyches. These women have seen too much bad behavior in real life to pretend that it ended with #MeToo. It’s refreshing, then, to find in Breillat’s cinema stories in which the women behave just as badly as the men – not as objects to be acted upon, but as subjects who act out, strike back, and destabilize with a force all her own. Here, at last, is a version of gender equality that’s not trying to sell something.

___