The art of Emilio Prini (1943–2016) is apodictic. The statement might sound peremptory if it were not for the fact that, when interfacing critically with such an artist and production, hesitating or over-structuring is not an option. To try to understand Prini, one must either have a virgin eye (which art historian Ernst Gombrich contended is a myth) or to lower oneself into his tangible and intangible space so deeply that one ends up understanding him without the conspiratorial imaginings of hindsight.

Featuring more than 250 works produced between 1966 and 2016, “… E Prini” wholly exceeds the usual considerations of the artist in relation to Arte Povera and its theorist and champion, Germano Celant, who included Prini in “Arte Povera – IM Spazio” (The Space of Thoughts), the 1967 exhibition in Genoa that marked the influential art movement’s birth. Preceded by an ellipsis, the title and curatorial discourse of MACRO’s retrospective unravels chronologically along the museum’s perimeter walls measuredly and canonically, seemingly toning down curator Luca Lo Pinto’s editorial style – apparent in titling, captions, and unorthodox setups – in favor of meticulous research and cataloguing Prini comprehensively.

Views of “... E Prini,” MACRO, Rome, 2023

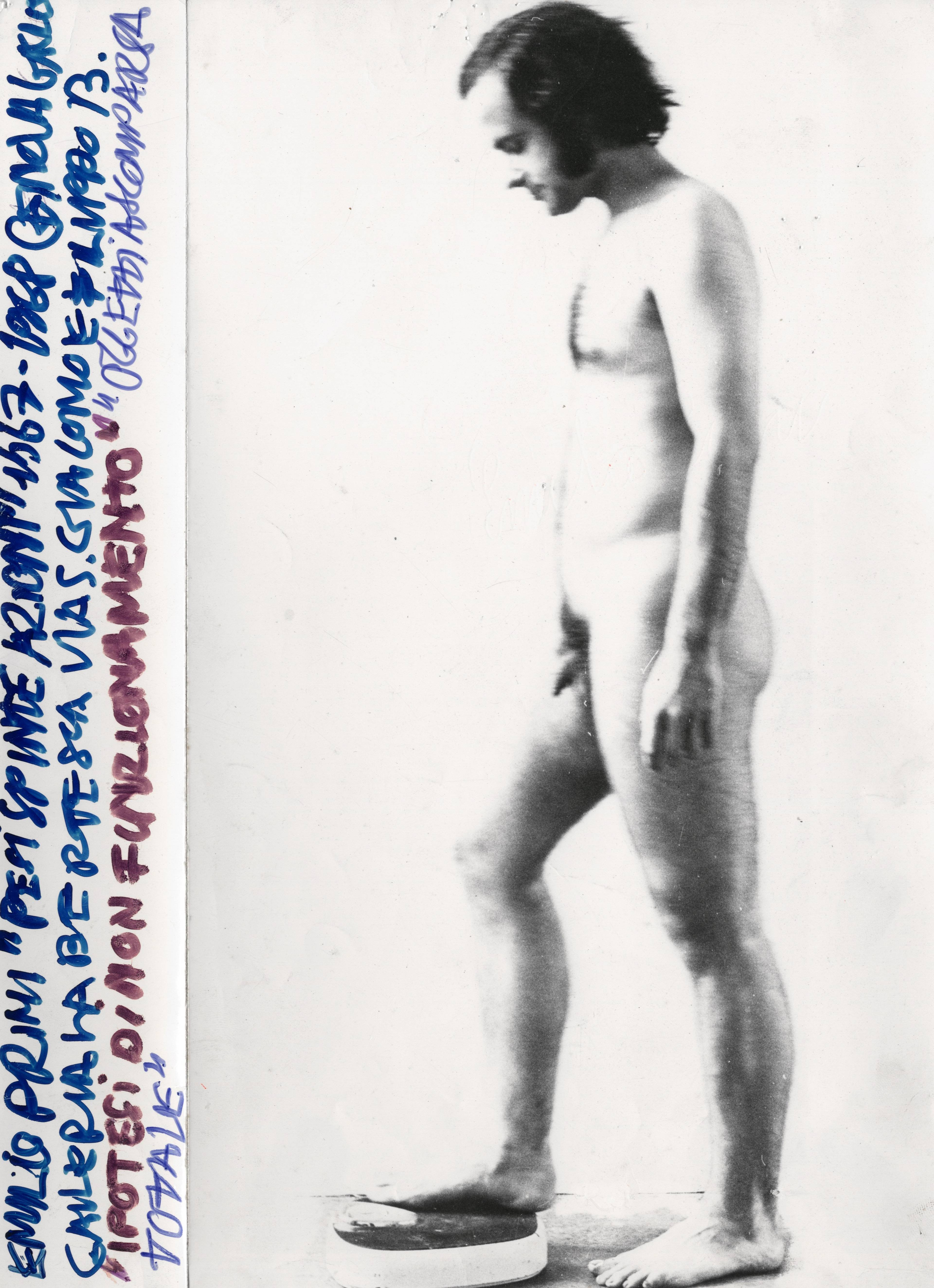

Ho preparato una trappola per Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie (I Set a Trap for Alice in Wonderland, 1968), written in red felt-tip on white paper, nicely frames Prini’s quintessentially indecipherable artistic practice. Does he intend to thwart art history? himself? His work? Probably all these things together, by systematically removing himself from the art world while remaining on its threshold, liminally between absence and presence. Photo-documented actions like Sei passi da un metro (Six Steps from One Meter) and Strada in salita (Uphill Road, both 1967) are the artist’s earliest attempts to measure space, the latter a survey of public architectures in Genoa and Rome, in relation to his own body and those of people close to him, mostly from behind, interested not in his subjects’ identities, but in their spatial presence.

Situated in the indefinable area between milieu and form, Prini’s methodical subversion of seriality emerges in innumerable printed matter: telegrams confirming his participation in exhibitions; hundreds of A4 drawings typewritten with an Olivetti 22 (1970– 74); leaden sheets, each weighing as much as one of his arms, imprinted with poetic notes like “Un’altra ipotesi sul vuoto” / “Ho percorso una strada in salita” / “Ho ottenuto un movimento” (Another hypothesis on the void / I travelled an uphill road / I got a movement). His practice continuously bedeviled its own commodification by using contingencies like emptiness, duration, and the relationship between space and image. “I don’t create, if possible,” a topical declamation whereby the logic of producing renders its own erasure.

Views of “... E Prini,” MACRO, Rome, 2023

Prini’s art subtends a wry documentary attitude that Lo Pinto skilfully assimilates, in contrast to the linearity of the wall-mounted works, in freer arrangements that recall seminal Italian projects like the “Deposito d’Arte Presente” (Depot of Present Art, 1967– 69) in Turin. Here, we find works such as Mostro – Una esposizione di oggetti non fatti non scelti non presentati da Emilio Prini (Monster – An Exhibition of Objects Not Made Not Chosen Not Presented by Emilio Prini, 1975), a to-scale photograph of a small, yellow window built adjacent the entrance to an eponymous exhibition at Galleria Toselli in Milan; X Edizioni (X Editions, 1986) a four-copy print run of thirty-six reproductions of notebooks detailing a never-materialized auction at the same gallery; and a series of iron and wood sculptures cast from his urban surveys of the late 60s for “Fermi in dogana” (Customs Stops), a 1995 exhibition at Strasbourg’s Ancienne Douane, which itself evoked the loss of Prini’s Fermacarte (Paperweight, 1968) in transit to the 1969 show “Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form.” “If Prini were still alive, this exhibition would probably never have existed,” Lo Pinto says during our visit, nodding to the possibility of sabotage by an artist who thought of art, whatever its form, as never definitive or accomplished.

“… E Prini” is a necessary exhibition for the art of our time. Prini is perhaps one of the very few artists to have actually lived out Allan Kaprow’s dictum that the boundary between art and life should be kept as fluidly indistinct as possible. Many artists today are committed (verbally if not materially) to taking a political side and fighting the copious shortcomings of the system they work within. But even moved by the highest of ideals, they cannot escape its vitiated, increasingly pyramidal laws, which sideline those ideals in favor of scalar economics or bare survival. Even where we see practices that tend toward the immaterial, behind the scenes, a corresponding material production is often more or less palatable.

Revisiting Prini today enlightens us as to how the ethics and will of an artist can, with difficulty, coexist with a system that catalogues, sells, and too quickly historicizes. His work shows us the face of our present: the imperative to be in the art world at any cost.

View of “... E Prini,” MACRO, Rome, 2023

___

“… E Prini”

MACRO, Rome

27 Oct 23 – 31 Mar 24