Since 2011, it would seem that the Venice Biennale milestones the piecemeal deconstruction of the modernist grid for reading the world, leaving us to recurrently wonder which part of this framework will be dynamited next, and in which direction its splinters will fall. In 2013, the edition directed by Massimiliano Gioni redefined the artist as a medium/ encyclopedist outsider; two years later, the late Okwui Enwezor injected a strong dose of Marxism into post-colonial discourse; most recently, in 2022, Cecilia Alemani indulged in a bold, anti-patriarchal rewriting of 20th-century art history. This year, Adriano Pedrosa’s exhibition was expected to deliver a similar statement and, in turn, to redefine the image of the artist. Its very title, “Foreigners Everywhere,” seemed subversive in the Italian political context, governed for the past two years by the extreme right. But, at the end of the day, is there really any evidence to believe that this government feels threatened?

Stretched to the point of the Freudian unheimlich (uncanny), foreignness winds up losing all its subversive intent. “Wherever you go and wherever you are,” Pedrosa says, “you will always encounter foreigners – they/we are everywhere,” and, no matter where you find yourself, “you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.” But, to assert that everyone is a foreigner to someone or something is to willfully blur or limpen the concept. The problem is that the record 330 artists invited here are subject to a kind of Borgesian classification: emigré Italians, queers, those forgotten by history, self-taught artists, rural communities, artists from the Global South ... They are all foreign here, certainly; but, more importantly, they are foreign to each other, as if lost in an exhibition whose common thread lies less in a clearly articulated concept than in a slogan that, quickly forgotten during one’s visit, serves only to line up, one after another, the art world’s themes du jour. Pedrosa seems to have lost sight of his concept along the way, as the real thrust of his exhibition – cultural heritage – remains offstage of his official discourse. All that remains is folklore, the kitschy side of the vernacular, a notion that affirms the ever-dialectal character of artistic practices, whatever their origins.

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–11, eight-channel video, color, sound. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Among the emergent motifs is the idea, strongly perceptible throughout, that artists must perform their work, i.e., to represent its meaning and message as physical persons; the sanction of a work of art gives way to the political coordinates of bodies, which has become the basis for indexing aesthetic values. In short, what the artist is becomes more important than what they produce. This principle of the geolocalization of artistic thought (where do you live? from where do you speak?) intertwines with that of the embodiment of political lines (what kind of body do you have?) to utterly virtualize artistic positions. In other words, GPS and Instagram together generate the dominant aesthetic criteria – a real boon for curators who work with their ears rather than their eyes. Yet, this extreme valorization of place and body leads to a striking paradox, from which “Foreigners Everywhere” never extricates itself: namely, that the places where we are born and the body in which we grow up are givens. Whereas being a foreigner should be seen as a factor in overcoming received identities, “Foreigners Everywhere” celebrates these as unsurpassable facts, in a kind of naive essentialism.

What contemporary art teaches us – and we should certainly reread Judith Butler before visiting Pedrosa’s exhibition – is precisely to refuse to be assigned bodies and geographies, because such fixed identities are nothing more than tools for the powers that be. Through this folklorization of artistic positions, the exhibition unwittingly denies identity any fluidity, while deigning to choose neither between opposing values, nor between the reclamation of traditionalism and the reinvention of sexual and political identities. Thus, consciously or not, “Foreigners Everywhere” celebrates a patrimonial regime of art, modeled in the absolute by traditional grammars.

Photos: Marco Zorzanello

Lydia Ourahmane, 21 Boulevard Mustapha Benboulaid (entrance), 1901–2021, metal door, wooden door, nine locks, concrete, plaster, brick, steel frame, 220 × 200 × 16 cm

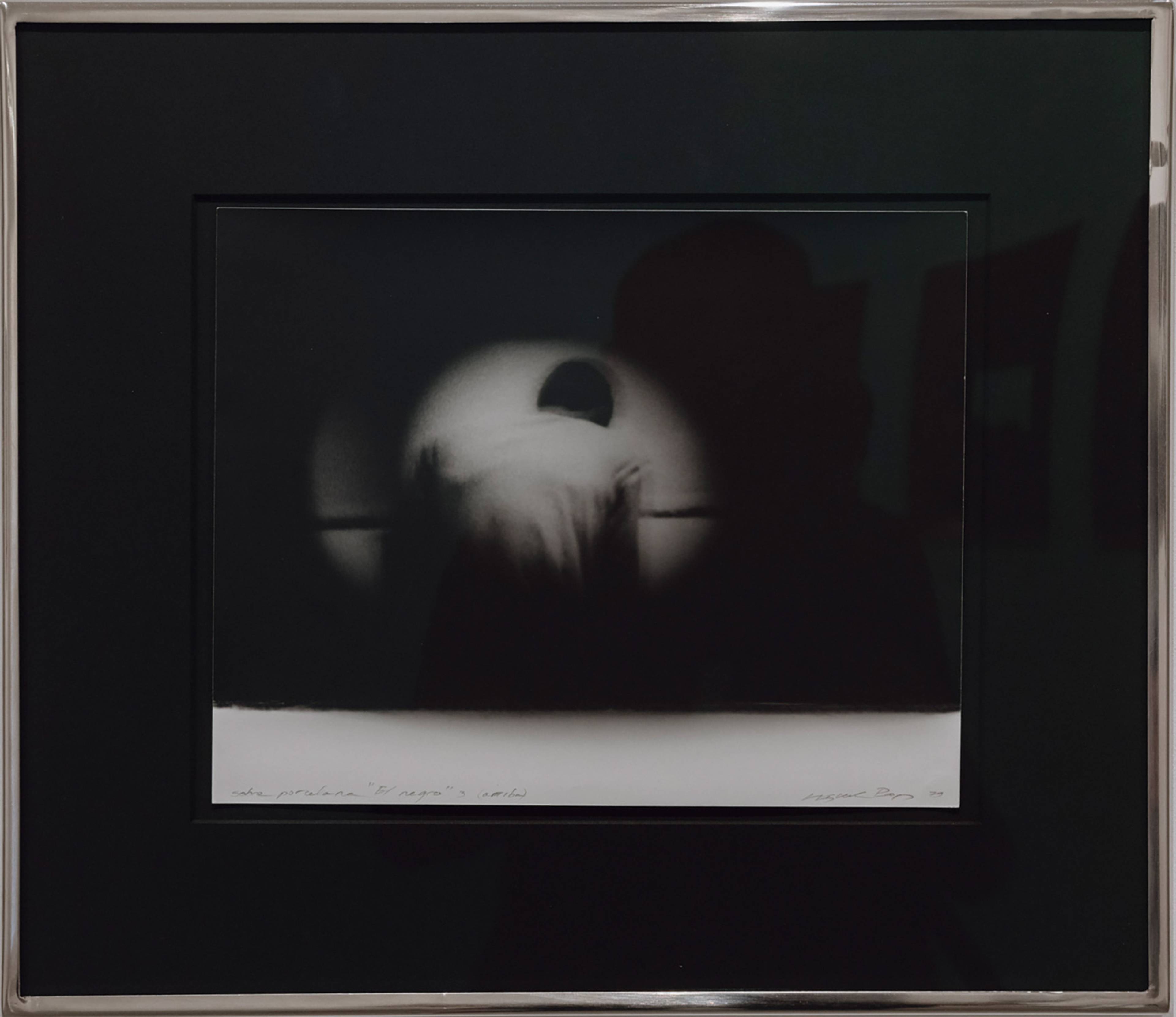

Where there are interruptions in this univocality, it is thanks to artists such as Lydia Ourahmane, whose conceptual and formal precision in Entrance (1901–2021) is reminiscent of Dan Graham, as well as Bouchra Khalili (The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–11), Nil Yalter (Topak Ev, 1973; Exile is a Hard Job, 1977–2024), and Teresa Margolles (Tela Venezuelana, 2019), who tackle head-on the political question that the exhibition seems to address. Similarly, the skillfully staged confrontation between Dean Sameshima (“being alone,” 2022) and Miguel Ángel Rojas (El Emperador, 1973–80; El Negro, 1979), from the angle of queer clandestinity, lets us imagine how the exhibition might have been, had it really dealt with its putative subject. There are other remarkable works in “Foreigners Everywhere.” Abel Rodríguez (Sin título, 2023; Centreo el terreno que nunca se inunda, 2022), a major Amazonian artist, could have been Pedrosa’s emblematic figure. Instead, he finds himself in an anecdotal context that trivializes his work, just as Brett Graham’s impressive piece (Wastelands, 2024) rubs shoulders with, but doesn’t really speak to, the pictorial narratives of his father, Fred Graham (Whiti Te Ra, 1966).

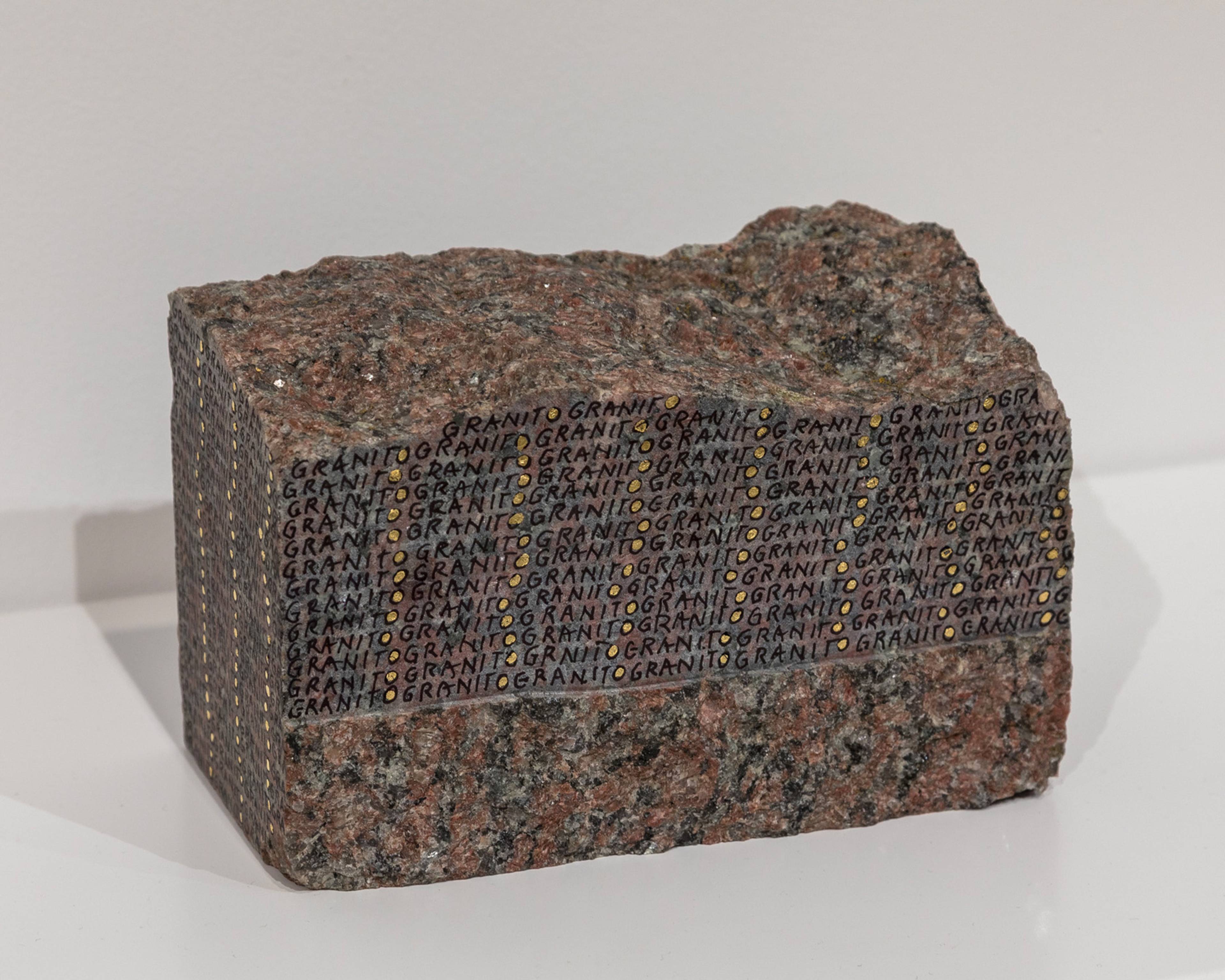

Greta Schödl, Granito rosso Sierra Chica, from the series “Scritture,” 2020, india ink and gold leaf on red granite, 13 × 20.2 × 10 cm. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Abel Rodríguez, Centro el terreno que nunca se inunda (Center the Land That Never Floods), 2022, ink on paper, 70 × 100 cm. Photo: Matteo de Mayda

Dean Sameshima, from the series “being alone,” 2022, ten Archival inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper, 59.5 × 42 cm each. Photo: Matteo de Mayda

Miguel-Angel-Rojas, from El Negro, 1979, four vintage silver gelatin print, 20.3 × 25.4 cm. Photo: Matteo de Mayda

Meanwhile, previously invited to the Biennale by Cecilia Alemani, the mighty Jaider Esbell must be turning in his grave today. The 2022 exhibition excelled both in its choice of artists and as an exercise in revising recent history, because Alemani had a point of view, a radical feminist angle that she held to the end. But here, the rediscovery of forgotten artists resembles a simple Warholian moment: Fifteen minutes will suffice. This lowering of standards is the exhibition’s main drawback, epitomized by the fact that Rember Yahuarcani puts into perspective a visual heritage whose formulae his father, Santiago, is merely allowed to repeat.

Another striking paradox: Whereas Massimiliano Gioni’s 2013 exhibition equally valued “naïve” aesthetics and community practices and presented them as a departure from modernist tradition, Pedrosa insists on these practices as familial transmissions, framing the work of those artists as the fruits of a new, fragmented academy. In this field of eccentric practices, works by Greta Schödl (Piccolo marmo rosato, 2020; Granito rosso Serra Chica, 2020; Marmo basso calcareo, 2023) and Romany Eveleigh (Pages, 1973; Tri-Part, 1974) are nonetheless very convincing, as is Emmi Whitehorse’s painting Cópia (2023). Conversely, Lauren Halsey’s sculptures (keepers of the krown, 2024) say more about the urban kitsch of Los Angeles than about decolonial struggles, while Victor Fotso Nyie’s academic bronzes (Malinconia, 2020; Veglia, 2023; Gioia, 2023) and Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s use of Agnes Martin’s painting as an anecdotal background (“Do Not Agree with Agnes Martin All the Time,” 2022–23) remain perplexing (not to mention the gigantic room devoted to Louis Fratino’s rather conventional paintings, among many average works).

Evelyn Taocheng Wang, Tulip in Whisky and Imitation of Agnes Martin, 2023, acrylic, gesso, pencil on linen canvas, 185 × 185 cm (left); & Sugar Powder Bamboo and Imitation of Agnes Martin, 2023, acrylic, gesso, pencil on linen canvas, 185 × 185 cm (right). Photo: Matteo de Mayda

More generally, “Foreigners Everywhere” favors forms of conservation over generative ones, tradition over singularity; has innovation been deemed too “modernist” not to be washed out with the dirty colonial bathwater? While the claim to the vernacular takes on a certain (positive) meaning in a context of ecosystem destruction, here, it gives the exclusive impression that the world we live in is made up of human parks to be preserved. In this context, the Belgian Pavilion, celebrating northern folk festivities, could have won the Golden Lion for consistency. In the end, “Foreigners Everywhere” does deliver a statement: that contemporary art has become a global but compartmentalized safe space, designed to preserve the world as it was, rather than a place for inventing what the world might become.

___

“Foreigners Everywhere”

Central Pavilion & Arsenale di Venezia

60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia

20 Apr – 24 Nov 2024