For those unfamiliar: Just Above Midtown (JAM) was a gallery that operated in three Manhattan locations between 1974 and 1986 and made a significant contribution – if one regularly omitted by art history – to New York’s Black artistic community in the last quarter of the 20th century. The space founded on 57th Street by then twenty-five-year-old arts educator Linda Goode Bryant functioned as much as a public forum and community resource as it did as a gallery, building an infrastructure of mutual support into its very DNA.

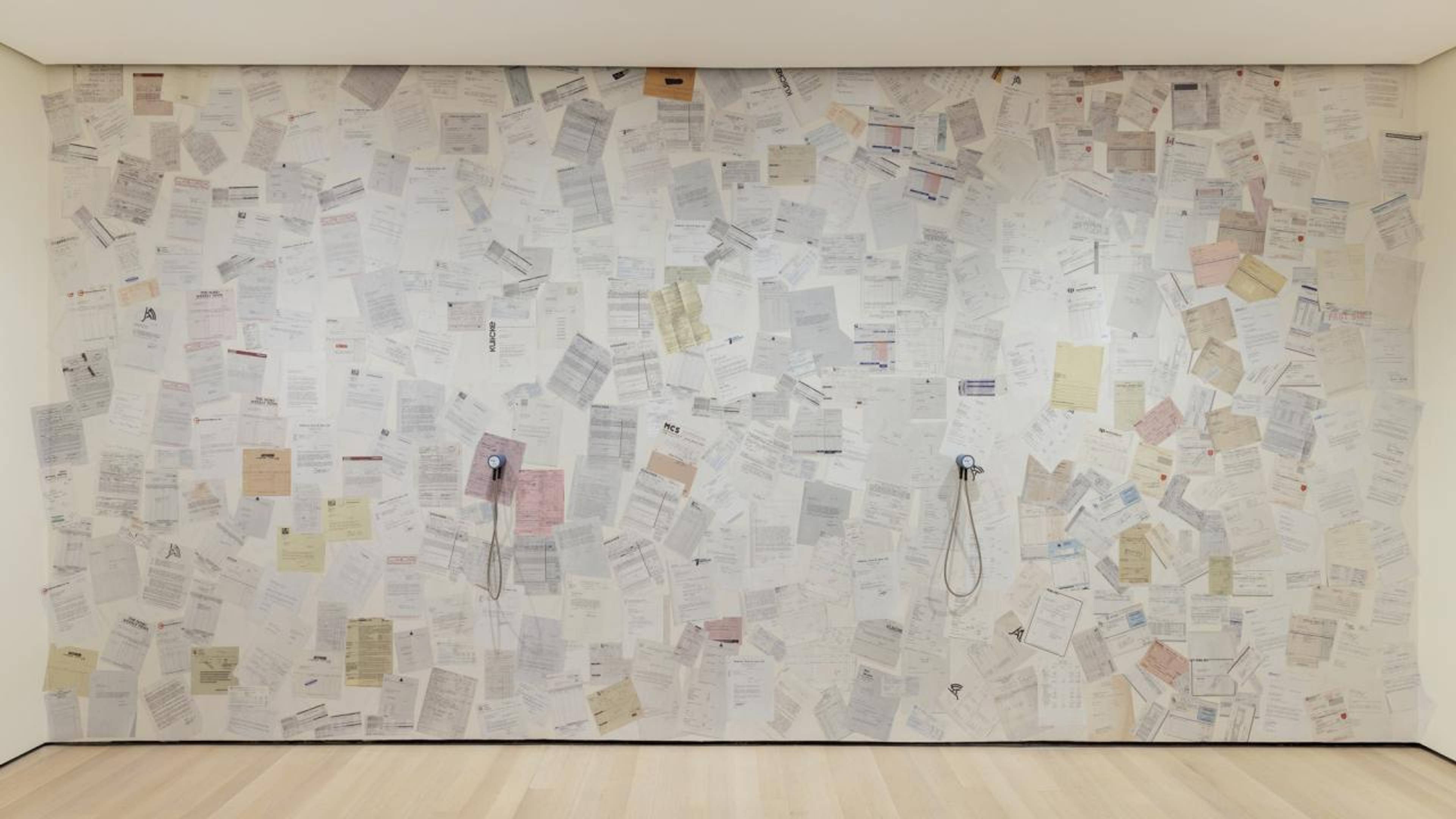

The retrospective “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces” presents the work of JAM through a somewhat hybrid method. While the loose temporal progression of the gallery’s history is punctuated by grouped selections of the exhibitions it hosted (by the likes of David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Betye Saar, Maren Hassinger, Howardena Pindell, and Randy Williams), “Changing Spaces” goes beyond simply presenting iterative micro-period rooms, instead mapping out what might be possible when communities of artists reach laterally, toward each other, rather than upward, toward validation. Material ephemera operate as traces of these horizontal connections, breaking up the otherwise progressive temporal march: past due invoices, letters requesting reference for credit, educational materials, and various printed matter.

View of “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces,” MoMA, New York, 2022. Courtesy: MoMA, New York. Photo: Emile Askey

I’m biased, of course; I like the show not only because its selections feel both vibrant and supportive of certain revelations – Sandra Payne’s ink drawing series “Most Definitely Not Profile Ladies” (1986), for instance, share important formal notes with later work by Kara Walker – but because I believe art should always be presented in something like this manner; that is, with a focus on the community from which it emerges. The prevailing alternative – decontextualizing aesthetic agendas imposed by an art writer with a point to make (present company excluded, clearly) or a curator with a career to build – is a poor one: Under this paradigm, young artists embrace the notion that their model canonical figures worked under the guidance of a single, clear idea that was located in the studio and executed like a thesis. Emphasizing instead that a constant search for resources, meaning, and community shaped their practices is not only good for the artists that museums exhibit, but also for those artists that decide everyday whether they, too, will reach laterally or upward.

Outside the exhibition’s informationals, Goode Bryant has explained that she decided to start JAM following Hammons’s declaration that he did not show with white galleries. JAM’s support specifically for the type of experimental and abstract work he was known for (along with that of many others in the gallery’s orbit) was significant at the time. In a conversation with Thelma Golden, director and chief curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, excerpted in Studio Magazine , Goode Bryant explained, “Most Black-run art organizations in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens tended to exhibit representational work, which I called ‘red-green-and-black’ or ‘Black-women-nursing-babies’ art, because those were common elements.” Pindell described her own encounter with this schism to LookSEE in 2018 rather more aggressively: “Being abstract was also frowned upon in the Black community in the 70s, and people like Bill [William T.] Williams and myself were thought of as almost kind of traitors [...] I remember both Bill and I on different occasions went to the Studio Museum in Harlem with our work and the Director told us to ‘Go downtown and show with the white boys.’”

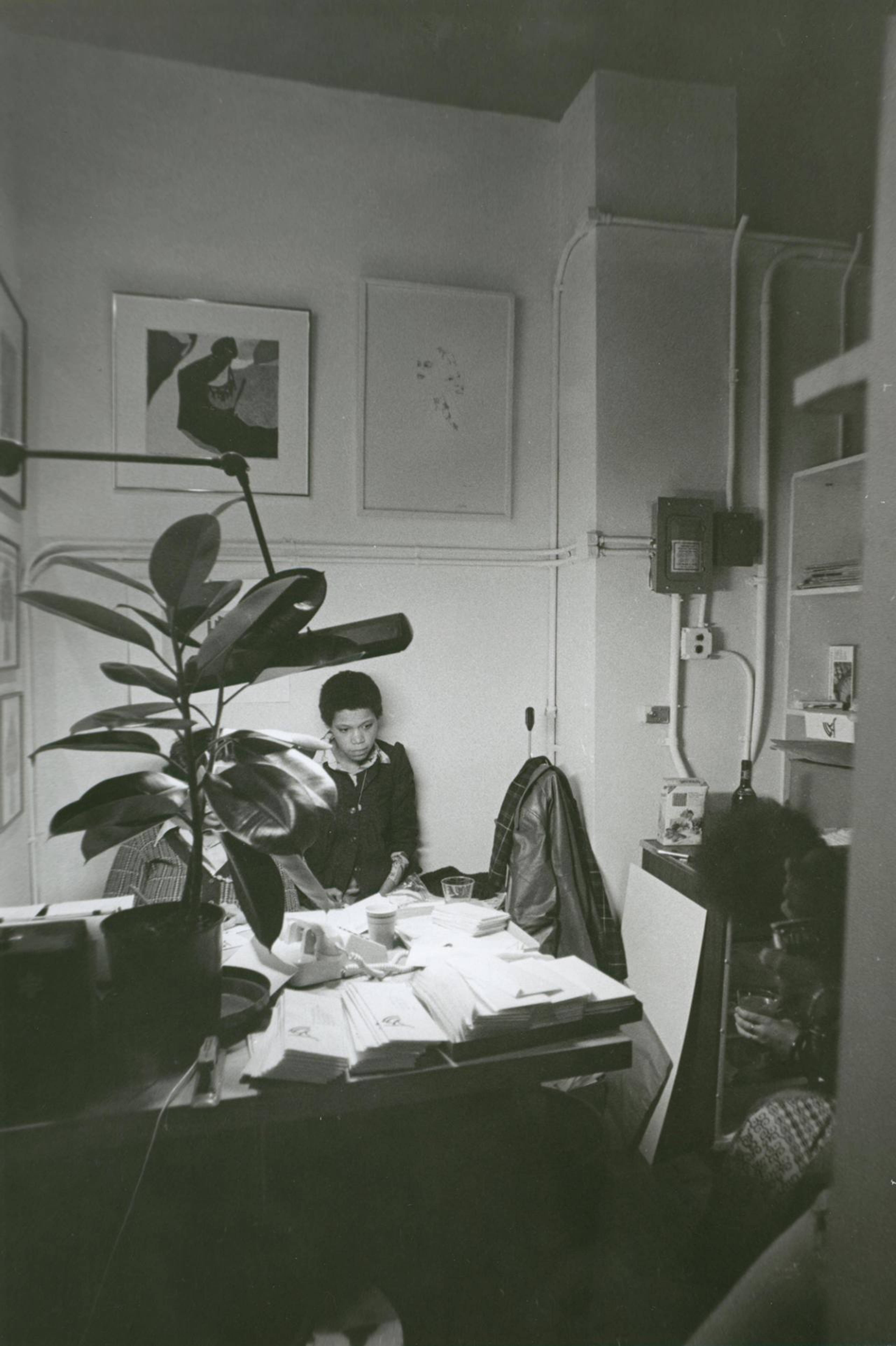

Janet Henry (obscured) and Linda Goode Bryant at Just Above Midtown, Fifty-Seventh Street, 1974

This concern about the place of Black abstract and conceptual art (and perhaps the case against such a false dichotomy) is addressed in part through Contextures (1978), a catalog by Goode Bryant and art historian Marcy S. Phillips that foregrounded JAM’s intentions not only to outline a thread of mid-century abstract work often omitted from the canon, but also to flesh out a developing mode of metonymic abstraction the authors identified as “contextural art.” Such a publishing impulse calls to mind adjacent, contemporary work on this topic, such as manuel arturo abreu’s 2020 lecture “An Alternative History of Abstraction,” that affirms the continuing relevance of this research.

Touching on canon-building, there are several structural questions about how “Changing Spaces” is situated against the backdrop of MoMA that should not be ignored. As a handwritten wall vinyl comparing the financial positions of MoMA and JAM in their respective first years makes clear, there were evident antagonisms between the two entities, as the latter worked to revise the very art-historical canon that the former wielded so much influence in shaping. As Suhail Malik, co-director of Goldsmith’s MFA in Fine Art, observed in a 2013 lecture, there is a frustration that results from an institutional gesture – such as MoMA’s toward JAM – that says, “Thank you for your critique; it's great. We'll incorporate it.”

View of “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces,” MoMA, New York, 2022

How should MoMA and institutions of its kind operate in relation to contemporary projects working in the lineage of JAM? Waiting until the hard work is complete, offering a retrospective, and laundering anti-canonical history back into a canon is certainly one approach. Furthermore, where do projects like JAM find themselves today? And what would it look like for MoMA to offer significant support before their overdue retrospectives become safe bet?

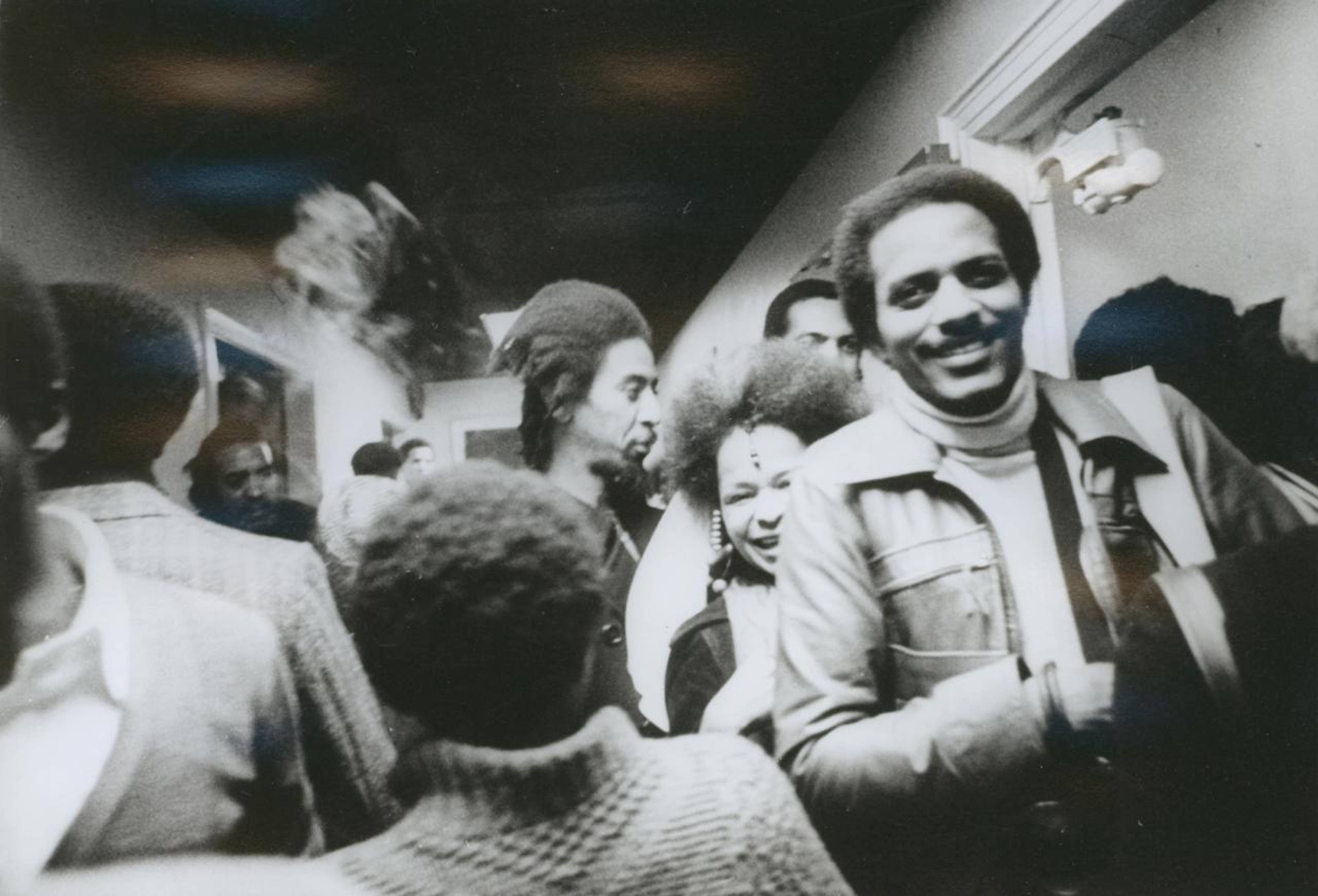

Barbara Mitchell (center) and Tyrone Mitchell (far right) at the opening of “Synthesis” at Just Above Midtown, Fifty-Seventh Street, 1974

___

“Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces”

MoMA, New York

9 Oct 2022 – 18 Feb 2023