And what if plants were also walls, brooms, flags? Stranger yet: garments, masks, Walkmen? Is it a question of tilting the head just right and squinting, as at a cloud, until the forms of the prefab imagination emerge from the garden? Or might certain flora simply grow of themselves that way? These and more unlikely apparitions have been coaxed from radishes, spring onions, carnations, and countless other cultivars since the 1960s by Kosen Ohtsubo (*1939). Enrolled in Tokyo’s Ryūsei-ha School, he began practicing a style of ikebana descended, first from rikka (standing), then through shōka (roughly, triangular), into a variant of jiyū-ka (freestyle) that uplifted “the appearance of plants.” Cut back – but certainly composted – in this modernist approach were classical structures of line and verticality, as well as the hierarchy of elements symbolizing cosmological order (heaven above human above earth). Emergent from Kosen was an ikebana less proper, more laissez-faire, somewhat mutant, with less pine and more daikon.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Radish Death-Cotheque, 1994, cotton, daikon radish, metal shelving, plastic

Kunstverein München’s retrospective-ish presentation, organized together with and including several works by one of the master’s students, Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, arranges the dense growths of Kosen’s work in two parts, one archival, the other still odorously, achingly alive. Left and right of the first gallery’s entry stairs are single, parallel rows of Kosen’s photos, mainly verticals, of his own ikebana. The oldest, 1/5 Rubbish of the Ikebana Exhibition of Ryusei School, 71 (1971), doubles as a lifetime’s thesis, daring as floral harmony a dumpy cloth sack near to bursting with Twomblyish mulch. Its neighbors are stranger still: a bone-like, glass half orb ringed by crimson yarn and combed over with a single, snake-tongued blade of New Zealand flax (What Can You See?, 1974); a mess of wood splinters tangled into a pillar of black floral wire, as if a swarm of bugs had exploded a sapling (A Jungle of Ikebana Wire, 1985); and, like a totem of giant garlic bulbs, a transparent sleeve billowing, burlesquely lit, around veiny loops of weeping willow (As a Stage Installation, c. 1980s).

View of “Flower Planet,” Kunstverein München, Munich, 2025. Where not otherwise noted, courtesy: the artists and Kunstverein München e.V. Photos: Maximilian Geuter.

The adjoining gallery is more sanguine, yet more feral. Almost in the doorway, like the entry to a shrine, a cleanly swept carpet of dirt, crinkled leaves, and blossomy potpourri surrounds a geodesic dome two-ish meters in diameter, thickly woven from basket-willow branches. Across its surface are matted longer-stemmed flowers, among them blue hydrangeas and bleached-out sugarbushes, along with crimped strips of chrome foil scraps of insulating foam board. Anchored to its base – the feminine yoni – by a single, electric candle, this linga is a Buddhistic evidence of the divine – in this case, of the very city streets from which Kosen has swept it together.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Linga München, 2025, 300 Basket willow branches, candle, metal frame, plastic and metal ties, scrap metal, soil, various flowers and leaves

Behind are the eighty-five-year-old artist’s latest ikebana and a pair of Oldham’s, all arrayed on pedestals that, tiled in glazed black, look incongruently like phone screens. Dashed with rain, the wind moaning through a cracked-open window teases out new scents: several yellowing lilies, their stems eking through a bolted iron box, are dustily sweet (Strange Callas III), while a brace of chubby green bananas, prostrate before a copper pot topped with a mustachioed dragon, are mellowly astringent (A Healing Spins Dreams). I poke my head towards ribbons of long beans to smell the withered carrots bedding a bell-like basket and breathe deep – only to see myself looking back, nostrils flared from a mirrored Christmas bauble. It’s not the only sight gag: A single traditional ikebana, of greening willow sprigs twisting from their bamboo vase like a hungry flame, is offset by, to one side, an old-fashioned bed-warmer playing at being a water bug (one magnolia leaf as its tail) and, to another, four wrinkly leaves of cabbage, each draped like an elderly hand over a delicately lipped ceramic plate. As though to say: Look how long we’ve been, how far we’ve come.

Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham, Penny Waking up from a Dream (detail), 2025, carrot, Chinese long bean, reflecting sphere, Japanese woven bamboo basket

Kosen Ohtsubo, 変貌するキャベツ / Transforming Cabbage, 2025, cabbage, ceramic vessels (made by Hee-sook Ko)

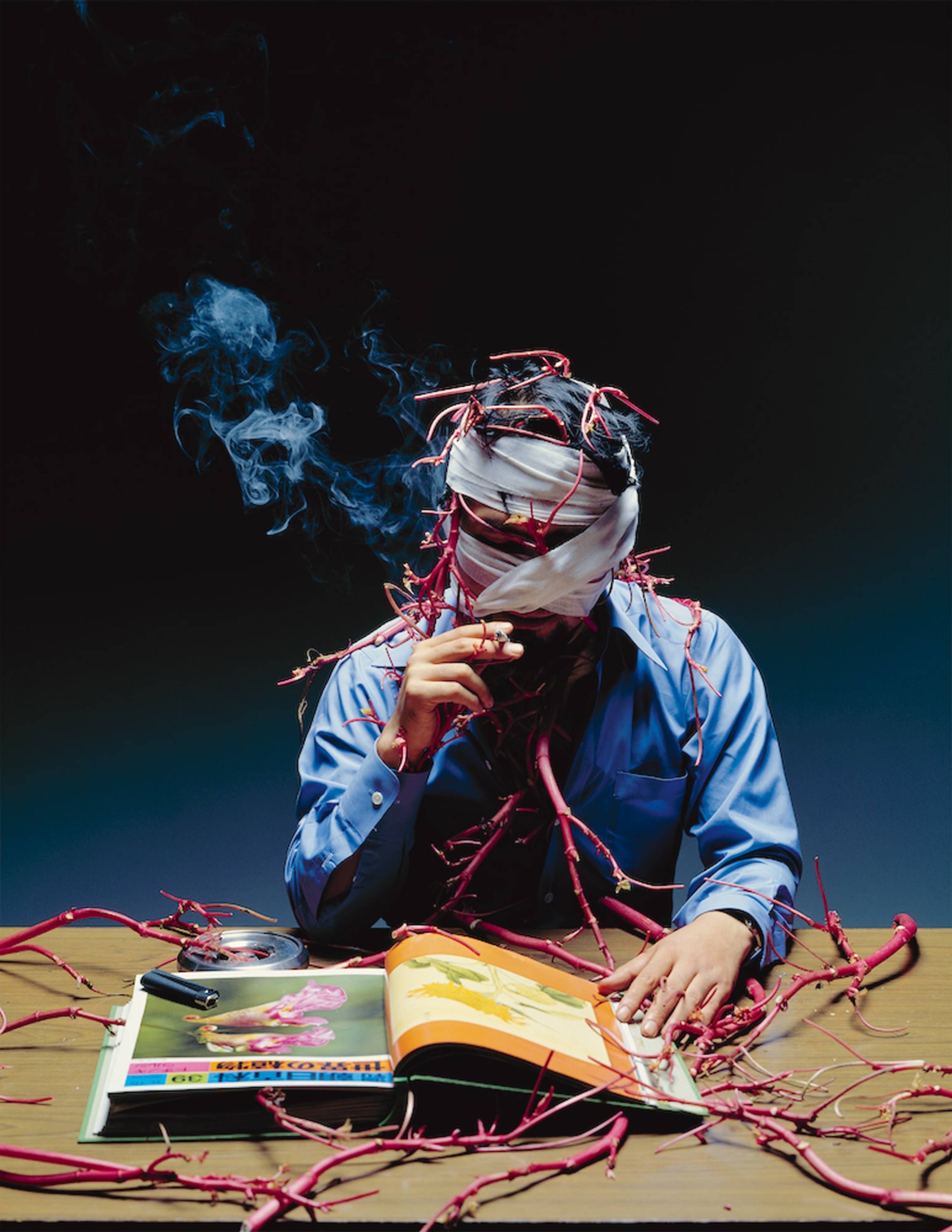

“Flower Planet,” like any bouquet, is less of an arrangement than a situation, the “still-lifes” in its arte povera abundance continually changing: Colors fade, shapes droop, textures coarsen, buds open. One man even becomes a plant pot. Botanical Man (1978) shows an office worker, under a thought bubble of cigarette smoke blue as his shirt, his face thickly striped with gauze, looking stoically down at a botany-book illustration of a thick red vine, which winds off the page and through his hair, out of his chest and his buttoned cuffs. In Kosen’s self-portrait, the artist is freshly overgrown, become a phorophyte in the red castor bean’s forever outward reach. Growing, in art-making as in biology, is moving and at the same time staying, dying the same ignominious death to enjoy the same ignominious rebirth. “Flowers should look as they do in the fields,” tea master Sen no Rikyū wrote nearly a half millennium ago, already opposed to an ikebana of opulence and strict technique. “We don’t give them life with our hands, but with our minds.” Look alive: Crocuses are pushing up through the Hofgarten.

Kosen Ohtsubo, 植物人間 / Botanical Man, 1978, the artist and castor oil plant. Photo: Ryusei Photo Department

___

“Flower Planet”

Kunstverein München, Munich

1 Feb – 21 Apr 2025