Nan Goldin’s (*1953) work has found renewed resonance in a moment when so many live under pain’s howl, and when the pinch of intolerance is felt by seemingly everyone, not least immigrants, queer people, the poor, the addicted. For that reason, seeing a trans body or a drag queen in The Other Side (1992–2021), Goldin’s homage to her transgender friends, lighting a cigarette or crossing a city street, inspires a feeling of defiant freedom. Her figures are not only themselves; they become unlikely icons for everyone’s own chafe against the corsets of repression.

For all its title’s finality, Goldin’s show is also about beginnings. Her photographs have always drawn from the irrepressible romance of the finale: the late night, the breakup, the end of the song. Here, Goldin’s photographs, many of them now classics, are shown within purpose-made “buildings” designed by architect Hala Wardé, through the slideshow format she has worked with since the early 1980s. The earliest works remain as absorbing as they must have originally been, rowdily sound-tracked in the bars and clubs of Boston and New York.

Picnic on the Esplanade, Boston, 1973, photograph. From the series “The Other Side,” 1992–2021

Fashion show at Second Tip, Toon, C, So and Yogo, Bangkok, 1992, photograph. From the series “The Other Side,” 1992–2021

Goldin’s project – effectively, candid photos of the people around her – has always been more dialectical than it seems. Like watching a film whose tragic ending we already know, making the happy parts all the more anxious, she works through opposition, conjuring the melancholy behind every smile. Each blitz of happiness hints at drama behind the door. This is heightened by her choice of form: The slideshow facilitates juxtaposition and reshuffling, to better bring out the surreptitious contrasts that give her work its trademark frisson. That’s one meaning of “dependency” in her career’s key work, the Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1981–2022): You can’t have freedom without the bondage lurking around the corner. Nearly every photo finds a way of capturing such tensions: They are not picturesque, in themselves, but rather chronicle the recovery of whatever is beautiful from the ugliness underneath.

The six slideshows in this smart, timely show, curated by Fredrik Liew of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, will be familiar to many viewers. Its staging at the Neue Nationalgalerie is also something of a homecoming for Goldin, who has spent time in Berlin since at least 1991. When I visited, all the pavilions were full, visitors of every age rapt, watching characters put on makeup. Putting on dresses. Smoking in bars. Reading Baudelaire in bed. Rarely, they look at the camera. More often, they look away. They strut, fight, kiss, smile. They take taxies, get sand on their butts at the beach. They get married. They die.

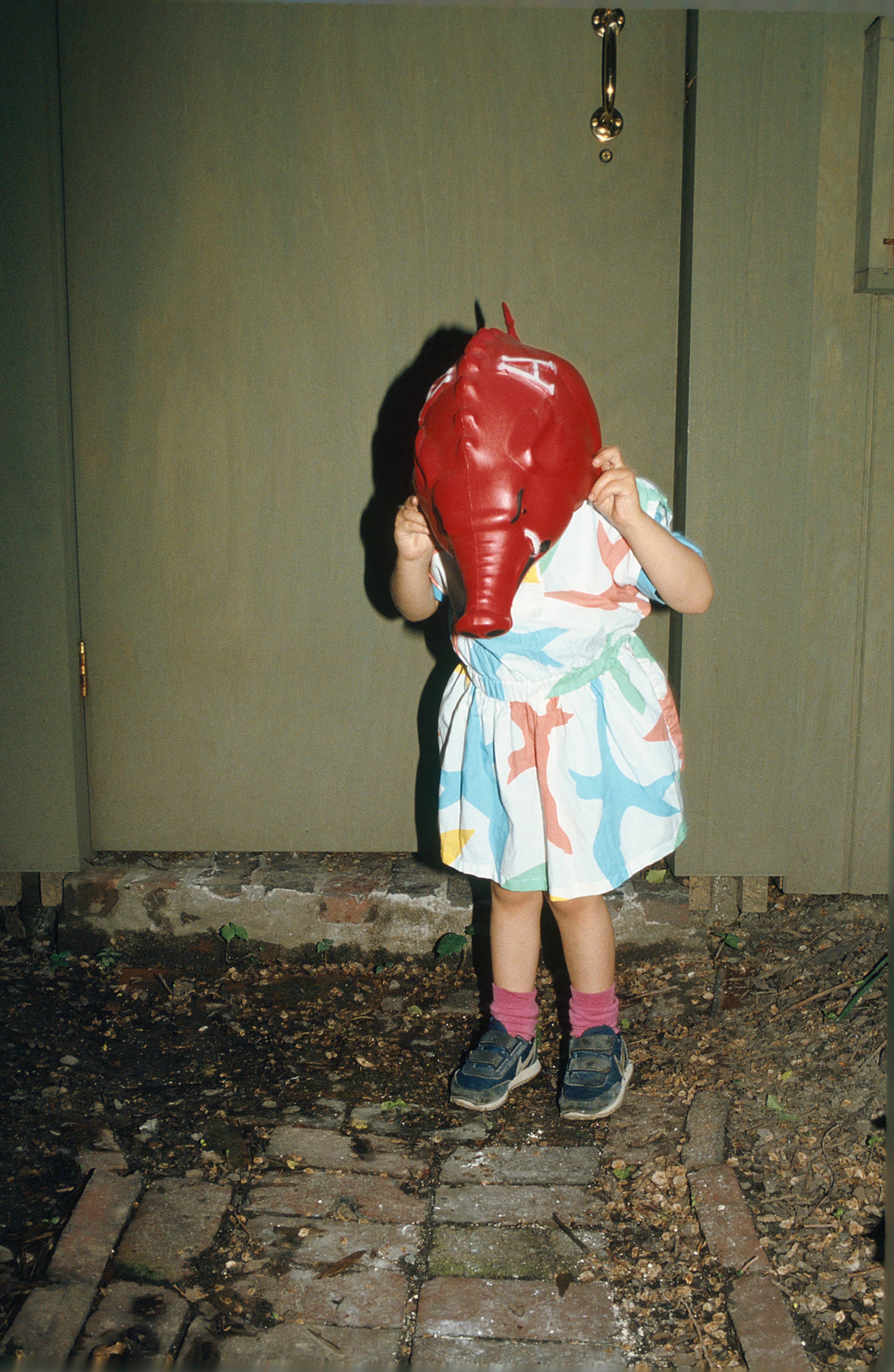

Elephant mask, Boston, 1985, photograph. From the series “Fire Leap,” 2010–24

Greer modeling jewelry, NYC, 1985, photograph. From the series “The Other Side,” 1992–2021

The Hug, New York City, 1980, photograph. From the series “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” 1981–2022

Goldin’s friends reappear throughout like motifs in a song; we meet them, construct stories about their lives, find meaning in their disordered kitchens, the tension of their bodies in bed, flung together and pulled apart. In Fire Leap (2010–24), which documents her friends’ children, but also parenthood and aging, the camera is attuned to the almost alien gaucheness of childhood, the way that clothes don’t ever really fit right, a kid’s raw emotion set free at the wrong time or place.

In Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls (2004–24), a portrait of her sister, who committed suicide aged eighteen, she lays bare the camaraderie of siblinghood and elevates it to a universal tragic irony: that we are almost constantly failing one another, and yet that we call this love. Everywhere in Goldin’s art, there is the regret of spoilt relationships. It’s in the sparkling chemicals smoked off tinfoil; the happy times on rough city beaches; a dead person’s photo on an ugly mantle. Hurt, as a possibility and a threat, always lurks behind us.

Self-portrait with eyes turned inward, Boston, 1989, photograph. From the series “Sisters, Saints and Sybils,” 1981– 2022

In 2025, this trait, this Felliniesque neorealism, is precisely what endears the photos to viewers: So often, they resemble those we carry with us in our pockets, only made more immersive and accessible by their presentation. Yet, only to a point. A slideshow takes back whatever it gives: Unlike looking at a photograph, we can never go at our own pace, or linger on one, jarring detail, nor bring ourselves closer; as in life, we are quickly jostled into the next scene. Cue the exhibition’s November 2024 opening when, within a thirteen- minute speech, Goldin rousingly decried the German political stance against Palestine, the war crimes and ethnic cleansing occurring in Gaza, and the complacency and censorship of “tongues … tied and gagged by the government.” “I decided to use this exhibition as a platform to amplify my position of moral outrage,” she said.

Another platform of her outrage – P.A.I.N., which organizes against Sackler family philanthropy – is powerfully, if quietly, framed by the work that stayed most with me here. Compiled from photographs of her own thrall under opiates, Memory Lost (2019–21) seems, at first, to be a portal into a druggy haze. Yet it’s here that I see Goldin’s ars poetica most clearly: The oblivion occasioned by drugs resembles life, in that the more immersed we are in the moment, the more we are unable to ever represent that immersion. It’s a film about addiction as much as photography, about art-making, and the tension it has between a life properly lived and the need to abscond from that life. Can we ever unite the two? Here is another kind of dependency, capturing the thrall of the endless night, the stubborn mornings, any artist’s frustrated need for continuous externalization. Most poignantly, it is about memory and the tollful experience of forgetting. What physician Gabor Mate says in a voiceover applies as much to photography as it does to drugs: It “gives me a sense of connection, sense of control, sense of power … Makes me feel more excited, less bored with life.”

___

“This Will Not End Well”

Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

23 Nov 2024 – 6 Apr 2025