In his 1990 text Seduction, Jean Baudrillard links pornography to the elimination of obstacles. “In a culture that … makes everything speak, everything babble, everything climax,” the pornographic imagination is a command to realize one’s full potential, to titillate every microfibre, to make sex endlessly legible. No more secrets: The radical obscenity of pornography lies less in its salacious content than in the stripping away of that which keeps desire in motion – friction, unknowability, murkiness.

Porn, of course, is also an industry. Even in its most graphic forms, it teaches us as much about distribution chains as it does about desire. Structured into five sections, each with its own curator(s) – for example, Elisa R. Linn’s East German sexual counter-publics, or Charles Teyssou and Pierre-Alexandre Mateos’s melange of artworks as corporeal excess – this exhibition at the Kunstverein in Hamburg poses the imaging of sex as a prism refracting the lead-up to the collapse of actually existing socialism in Europe and its aftershocks.

View of “Das Gold der Liebe II” (The Gold of Love II), curated by Charles Teyssou und Pierre-Alexandre Mateos

In his canonical 1998 film The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography, William E. Jones uses excerpts from Eastern European gay porn and audition tapes commissioned for the US market, to index the region’s gradual exposure to the tyranny of exchange-value. With an “atmosphere of coercion” permeating the videos, the liberalization of the market runs parallel to the liberalization (not the liberation) of sex; the seismic convulsions of the dying order rewriting not only the world but the body itself. The timid Slavic boys’ awkward breaking of the fourth wall owes to the newness of being filmed, their in-demand innocence supposedly not yet corrupted by post-Fordist capture of eros.

The standard opposition between sexually repressive communist regimes and their libidinally accelerated aftermath is complicated again in an installation curated by Angela Harutyunyan. In post-Soviet Armenia, VHS tapes clandestinely circulated in the late 1990s and early 2000s came to stand in for freedom from state-run television, as in a DIY “sphere of de-alienation.” This furtive media framed the conditions for works like David Kareyan’s Uncontrolled Desire to Disappear (2005), where figures such as a statuesque youth emerge from the water yet remain on the verge of being swallowed by the monochromatic background. As a sleazy, pitched-down edit of Delerium’s “Silence” (1999) fills the room, sexual emancipation feels like an ambivalent negotiation between state power and a consumerist order that promises freedom while scripting its limits.

View of “Sex Tapes: Desire of Technology and Technology of Desire,” curated by Angela Harutyunyan

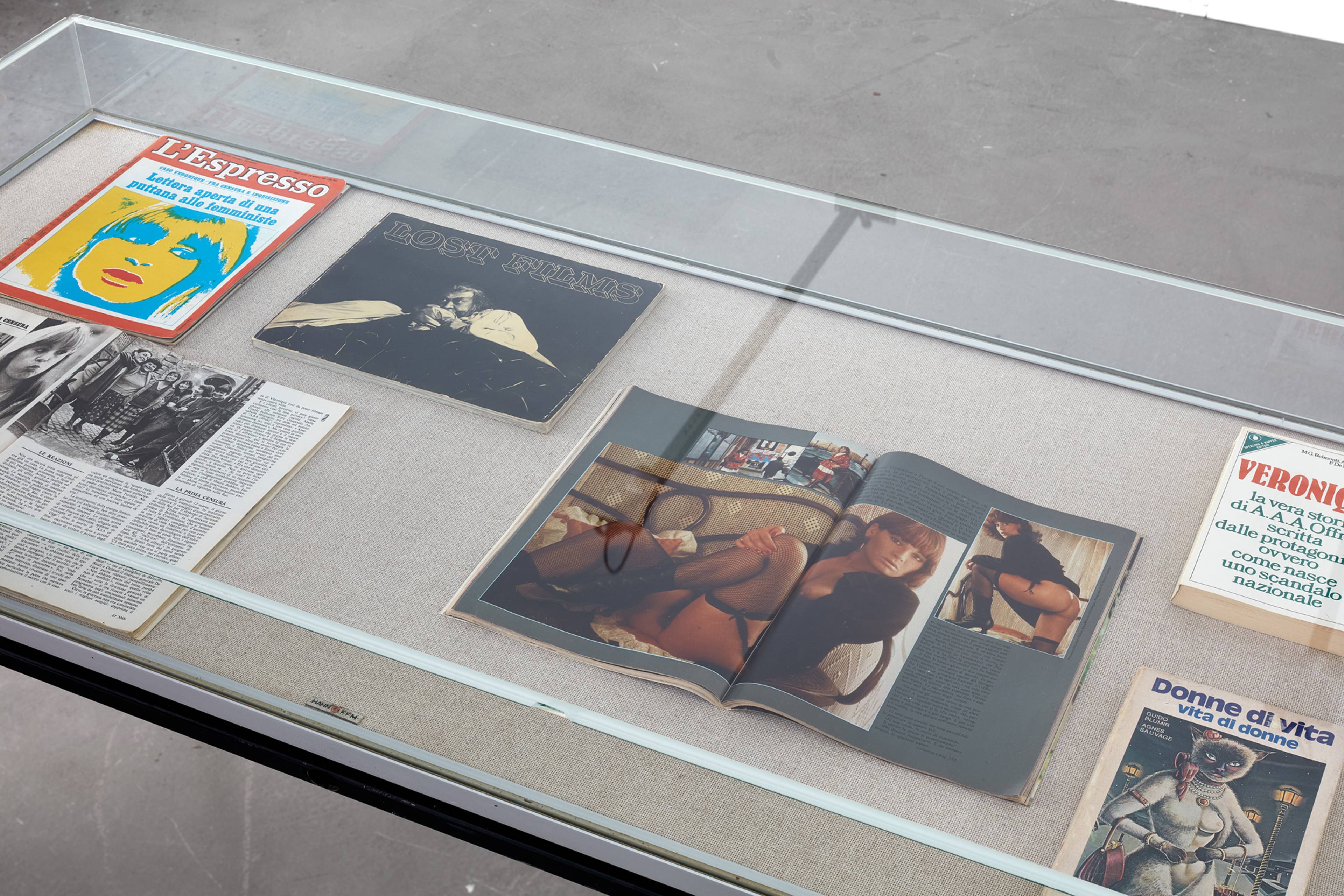

Sex work is the ur-form of commodified desire. A.A.A. Offresi (1981), occupying the room curated by film scholar Erica Balsom, is a lost film by a group of feminist Italian filmmakers. It is said to follow an anonymous sex worker’s encounters with her clients, but rather than staging an ethos of myopic empowerment, its political maneuver was to intercept the impersonal forces of capital, with most of the film consisting of tedious portrayals of monetary negotiations. As the collective later wrote: “The center of the investigation must not be the woman, but the demand, the need for prostitution.”

The film sought what Louis Althusser might call a “materialism of the immaterial, of the invisible” with the commodification of sex not represented viscerally but negatively, through its traces and effects. Avoiding the X-rated, Balsom’s austere presentation of the film-related paraphernalia (magazine clippings, a book-length account of its making, the script) embodies such poetics of withholding, and reflects a certain antiseptic museological grammar typical of Documenta-style exhibitions since the mid-2000s, which – however conceptually rigorous – risk curdling into bureaucratic boredom.

View of “The Secret Mirror, or, the Disappearance of A.A.A. Offresi,” curated by Erika Balsom

In the centerpiece of the show, Jean-Luc Godard offers another kind of archive. His Origins of the 21st Century (2000), commissioned by the Cannes Film Festival to mark cinema’s passage into its second century, assembles fragments of classic Hollywood, documentary footage, and images of genocide and fascism, interwoven with moments of spiritual and sexual rapture. In an interview about the film, Godard remarked: “maybe cinema is the lover and history is the beloved.” In his montage, scenes of historical atrocities are not simply flattened into equivalence with cinematic fiction; rather, life impinges upon art, violently interrupting it. Another kind of dialectical logic surfaces again in a sequence from Max Ophüls’s Le Plaisir (1952), where a character proclaims with delight, “Happiness is not fun,” crystallizing the show’s contention that ecstasy is always bound to corrosive self-undoing.

To a culture industry lusty for a vitalist return to the body, this exhibition counters that there is nothing intimate about intimacy. What might appear as the most direct instances of fleshy contact are shown to be mediated through the same abstractions that feed the flows of capital. Such framing feels especially pertinent today, in a hothouse of techno-optimized enjoyment where sexual dissatisfaction is cast as moral failure and content is fantasized as leverage for upward mobility (“OnlyFans model buys herself a $3 million house at just 23 years old”). This isn’t the apocalyptic end of pleasure; but a diagnosis of its inseparability from shipping and handling, as the hollow promise of the end of history cracks open into fissures that continue to widen.

“On the Origins of the 21st Century or the Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography”

Kunstverein in Hamburg

13 Sep 2025 – 11 Jan 2026