Was Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) the first post-internet artist? Parker Ito (*1986), casting an admiring eye over his use of print as a tool of mass dissemination, sure seems to think so: In 2016, he refigured three master engravings by “the German Leonardo” into photoshopped oil paintings, renaming them Melencolia 2, Me, Death and the Devil, and Me in my Study (all 2016). Using the stylistic trademarks of these works – density of line, non-hierarchical picture planes – Ito also interpolated his self-portrait, a character illustration of a knight with a backwards baseball cap commissioned from the comic artist Paul Pope, as though applying Dürer as a filter to his own life.

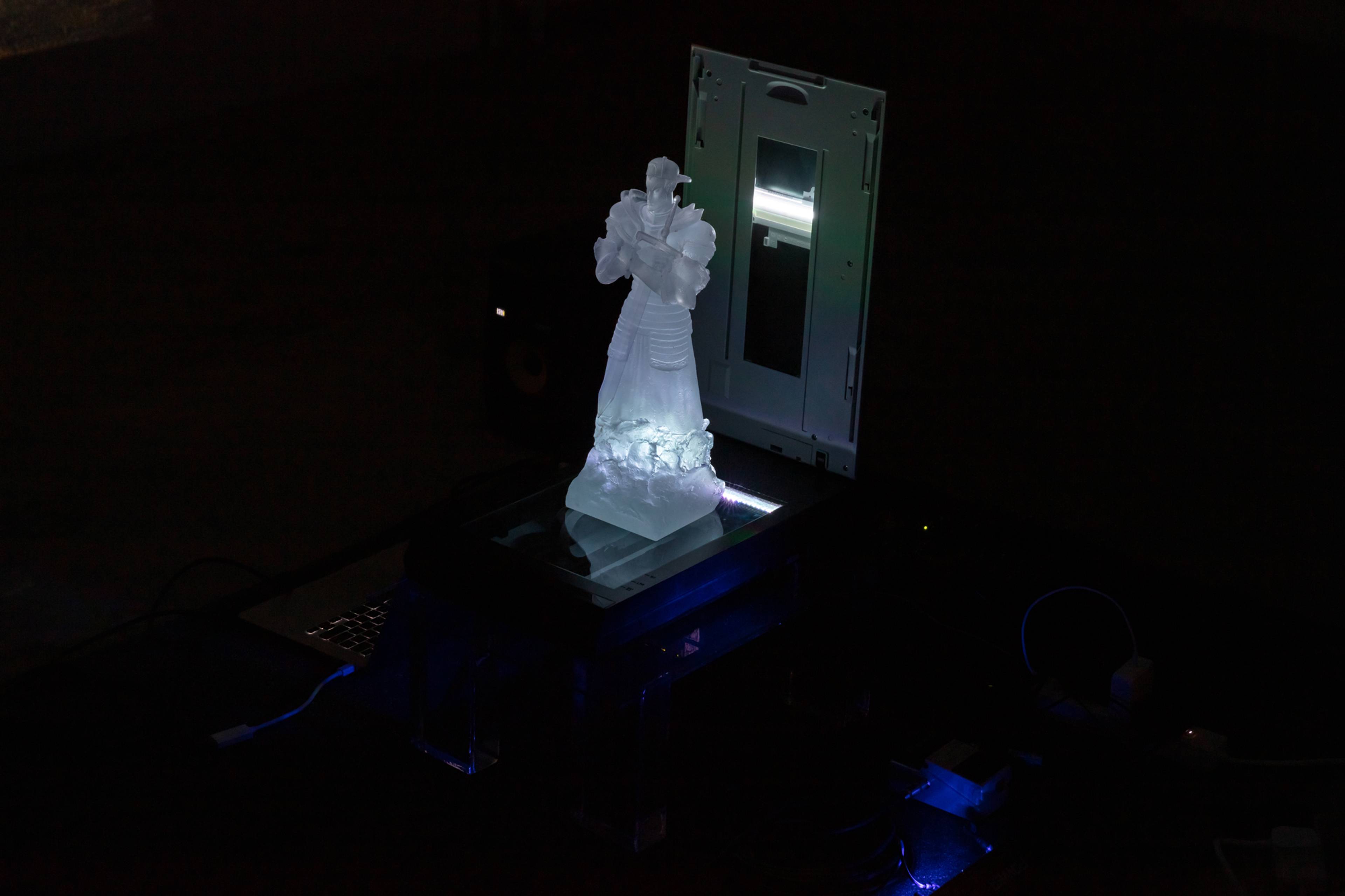

Ito’s journey into dissolving art’s temporal boundaries and hyper-contemporizing antique idioms of authorship, branding, and craft continues in “The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode.” The medievalism begins in Rose Easton’s entrance hall, where a trio of black wall paintings show death holding a winged hourglass, the blindfolding of Justice, and the daggering of a mounted knight by an armored foe. Upstairs, at the center of a room-filling multimedia installation, the artist’s self-portrait greets me as a small glass statue placed in the clam-like jaws of two Epson scanners, an imago functioning like an effigy, or the distribution of a royal’s likeness through multiplication, copying, and ultimately, de-objectification. Like a sun king, the artist’s voice, put through a MIDI reader, bellows “Why am I so beautiful” over a choir-like score, whose lilt embellishes the clerical atmosphere. As two projections flicker on, of the balcony view from Ito’s LA studio and a stretch of Cambridge Heath Road outside the gallery, the effigy goes red, shifting the mood as before a video game’s final boss battle.

View of “The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk, in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode,” Rose Easton, London, 2024

The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk, in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode (scanner sculpture) (detail), 2024, modified photo color scanner, glass, effects pedals, laptop, cables, extension cord, speakers, projector, color slides and slide projector, dimensions variable

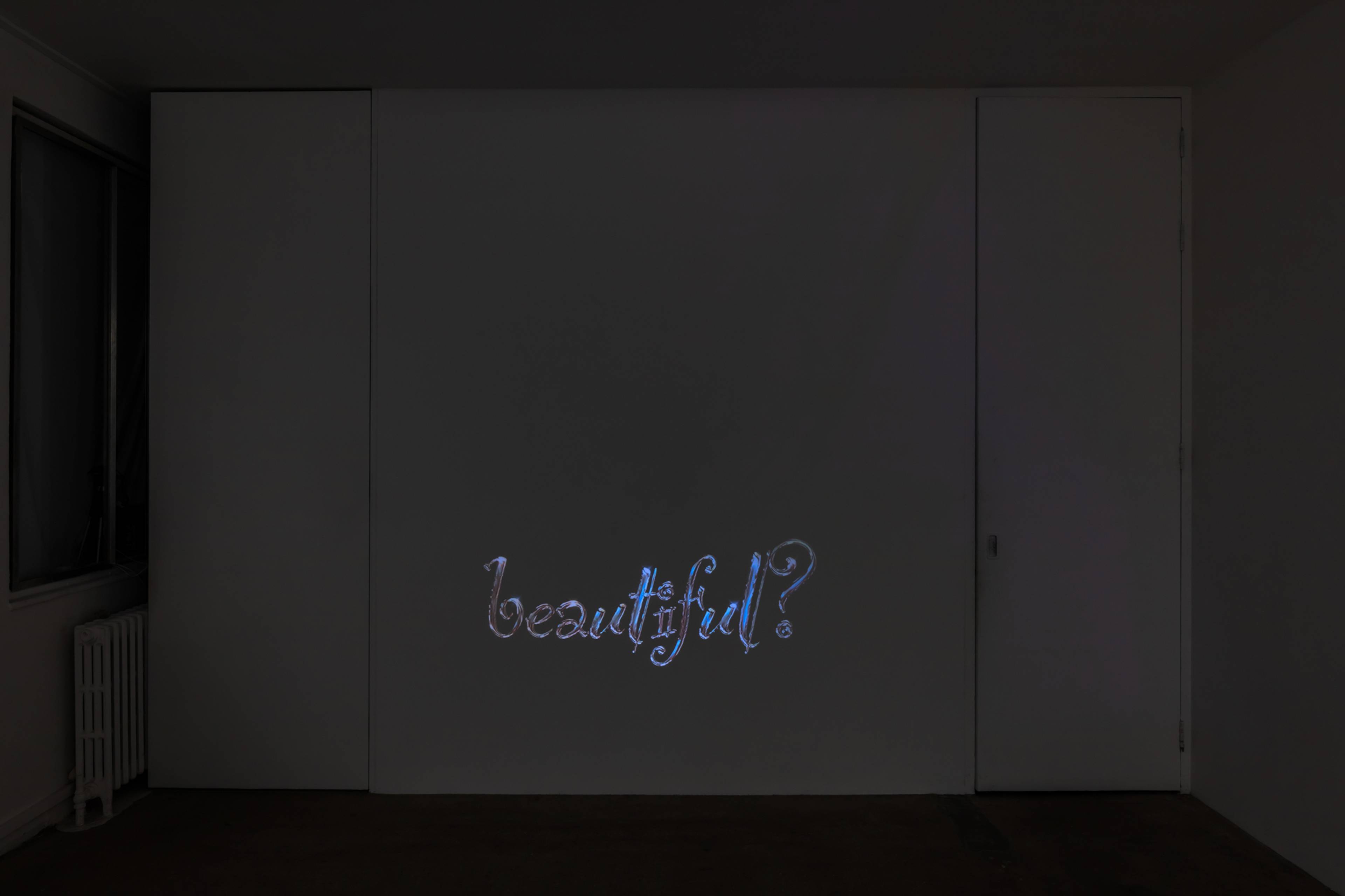

In one corner hangs a diptych of canvases layered with vinyl and run through an Inkjet printer, their centers filled with a knight leering out with the eyes of St. Lucy and, under a swirl of carmine paint, a pre-Raphaelite angel raising a sword. In opposite corners lurk the manga mercenary Guts and El Greco’s Saint Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1580), while two plaque-like blocks at the frame edges read “The Ag0ny.” and “The3 3xst$cy.” Carefully painted, the words mirror a third projection on the far wall, of a digitalized and 3D-rendered font wistfully asking: “Why am I so beautiful?” The artist seems to delight in mimicking the high-tech look, achieving the trompe-l’œil one might find on the ceiling of an opera house or in the translucent fabric of the Virgin Mary’s robe. Such escapist, trans-historical world-building and blog-style use of images brings to mind Nicole Stenger’s read of the early internet: “In this cold cubic fortress of pixels that is cyberspace, we will be, as in dreams, everything: the Dragon, the Princess, and the Sword.”

Parker Ito, The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk, in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode, part 2, 2024, ink, acrylic, modelling, paste, water soluble pastel, ink aid, GAC 100, paper and varnish on canvas, 203.2 x 304.8 x 2.5 cm.

Completing the Gesamtkunstwerk, The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding has transformed the entire room into a camera obscura, the Renaissance’s device for achieving optical verisimilitude. Though we might view the world outside the gallery through a live digital feed, the “dark chamber” only functions with enough daylight (hard pressed to find in November London) to reverse the exterior image and project it inside. Its real function, then, seems genealogical: to invoke a seminal era of artistic imitation, one that Jean Baudrillard saw culminating in the Baroque period’s proliferation of Stucco angels, columns, cornices, and, above all, over-decorated theaters. Descending through Richard Wagner’s Bayreuth Festspielhaus, a custom-purpose opera and theme-park grounds built for das Volk under pretenses equally revolutionary and romantic, Ito’s appeal is to dissolve the self into the collective through art. “Going to see the new Avatar movie is just as compelling as Yayoi Kusama’s infinity rooms,” he wrote in the show text for his “Medievl Times” (Viable Gallery, 2022) – a sentiment fulfilled in this total cybernetic drama, complete with data mining, live streaming, an operatic soundtrack, light shows, and medievalist cosplay. It is Baudrillard’s “theatre par excellence,” updated for an era of image oversaturation and rife with nostalgia for recognizable signs.

Ito grounds post-internet’s troubled (in)authenticities in a history of counterfeit, immersion, and dramatic sociality. In particular, the show iconizes a certain hyper-contemporary art, which divorces images from their origins to the point of rendering authorship moot, as an offspring of medieval craft practiced in multi-authorial settings: sculptural guilds, printing houses, and schools of painters who produced actual effigies and religious icons. Ito, who infamously claimed he could match the artistic volume of Picasso’s lifetime in five years – nay, five minutes – is simply using different means: scanners, printers, electronic as well as analog projections. As in Dürer and Wagner, in this Gesamtkunstwerk, we are proximate to greatness: a sensorial extravaganza where art, stripped of its referents, can win back its dignity.

View of “The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk, in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode,” Rose Easton, London, 2024

___

“The Pilgrim’s Sticky Toffee Pudding Gesamtkunstwerk in the Year of the Dragon, À La Mode”

Rose Easton

2 Nov – 14 Dec 2024