Boredom is the cardinal sin of the rave. We go to clubs to be in a submissive relationship with the sound, to have our selfhood undone by an intense aesthetic experience – not to wander around aimlessly. The sustain-release principle of much electronic music is crucial in averting this stasis, an ever-reliable drop that plunges us back into somatic bliss. But what if the break drags on endlessly, thwarting instant gratification?

One Sunday evening in May, at Panorama Bar – awkwardly listed as one of three venues for her retrospective “Reframed Positions,” organized by Halle für Kunst Lüneburg – Terre Thaemlitz (*1968), alias DJ Sprinkles, followed her four-to-the-floor, deeper-than-deep house selection with a half hour of jazz, disregarding Berghain’s logic of Aristotelian catharsis. Another time, she interrupted her set with a recording of a violently homophobic sermon, provoking visible disorientation. For Thaemlitz, such strategies are less transgressive gestures than experiments in what happens when, robbed of entertainment, you realize “you did not come to listen to music, but to unlisten to yourself.” Temporary escapes from everyday drudgery should not be moralized, but the audience’s impatience might be symptomatic of the taboo of unrealized potential, or, when doing something leads to nothing.

Terre Thaemlitz, 2004. Courtesy: the artist

Although DJ Sprinkles is responsible for some of the most dazzling releases of the past fifteen years, to her, music has always been one of the least interesting things about clubs. In the early 1990s, Thaemlitz, a self-described “non-essentialist transgendered person,” was a resident DJ at Sally’s II in New York, a trans sex workers’ club that served an educational purpose beyond the immediacy of the dance floor, where people could share transitioning experiences and access black-market hormones. These microcosms, intertwined with violence, isolation, addiction, the HIV epidemic, and underpayment, were barely utopian. While certain necessary correctives to club culture’s history have gained mainstream recognition, such as the pushback against ongoing whitewashing, prelapsarian accounts of “community” – projected onto the present – often obscure its burdensome past.

Please tell my landlord not to expect future payments because Attali’s theory of surplus-value-generating information economics only works if my home studio’s rent and other use-values are zero (2008), the title of one of Thaemlitz’s lecture performances, is typical of her engagement with the contradictions of value-producing labor, as opposed to artistic self-expression. We consider “underground” electronic music an authentic product/source of creative agency and extol its healing properties – of which there are certainly many – but this idealization obfuscates the exploitative dynamics of the music industry and is their necessary precondition. Her claiming to DJ for purely monetary reasons – while actively disliking it – raises suspicions, which highlights the challenge of envisioning a creative process focused less on personal fulfillment than on grappling with the inevitability of (self-)exploitation.

In Lüneburg, Thaemlitz’s 2003 net-arty film Lovebomb questions music’s redemptive connotations and our fetishistic attachment to “love” as an unambiguous ideal. Thaemlitz notes that, since its inception, house music has lyrically clung to categories of “nation” and “family,” unable to break free of institutions that have often hindered the flourishing of Black, Latino, and working-class queers. When raving is seen as a worldbuilding exercise in sexual liberation and Foucauldian “techniques of the self,” Thaemlitz’s negativity is invaluable, even if her readings sometimes bypass the coexistence of life-sustaining and life-destroying, theorized so aptly by the late Lauren Berlant.

If “house is a commodifiable desire you can own” and music is “aural capitalism,” then no one is able to fully transcend these processes.

Thaemlitz has had a lifelong interest in withdrawal, inaction and, to use one of her film titles, Deproduction (2017). Listing tragic episodes of childbirth and interfamilial sexual abuse, the film inveighs that having children is unethical and that families make democracy impossible. Nuclear family is a fraught model that privatizes care, but the conflation of reproduction and moral failure inadvertently perpetuates the stigmatization of “hyper-fecund” women in the Global South, while the film’s condemnation of medical transitions as binary-reifying is contentious at a moment when trans people are denied access to gender-affirming care. Still, by asking “What if one’s relationship to gender variance is one of collapse, of unbecoming?” the film unsettles the idea of transitioning as a straightforward pathway to non-alienated existence. Its analysis of sexuality’s commodification likewise remains pertinent amid the usurpation of queerness as an individual political redemption, detached from the sense of the world shaped by shared grievances.

If it sometimes seems she positions herself above the indelible antagonisms, Thaemlitz is candid in acknowledging her entanglements in material reality. In the film Soulnessless (2012), a scathing critique of religion and spirituality, she examines the use of audio devices by nuns in their convents in the Philippines. Decidedly not a disparaging “view from nowhere,” we witness the artist giving the nuns technical advice on how to make better use of sound. If “house is a commodifiable desire you can own” and music is “aural capitalism,” then no one is able to fully transcend these processes, but only to tweak them to openly address the inevitability of the hypocrisy we all constantly enact. Thaemlitz’s originality is not that of the romantic exception, but of an indispensably annoying cog of immanent self-contradiction.

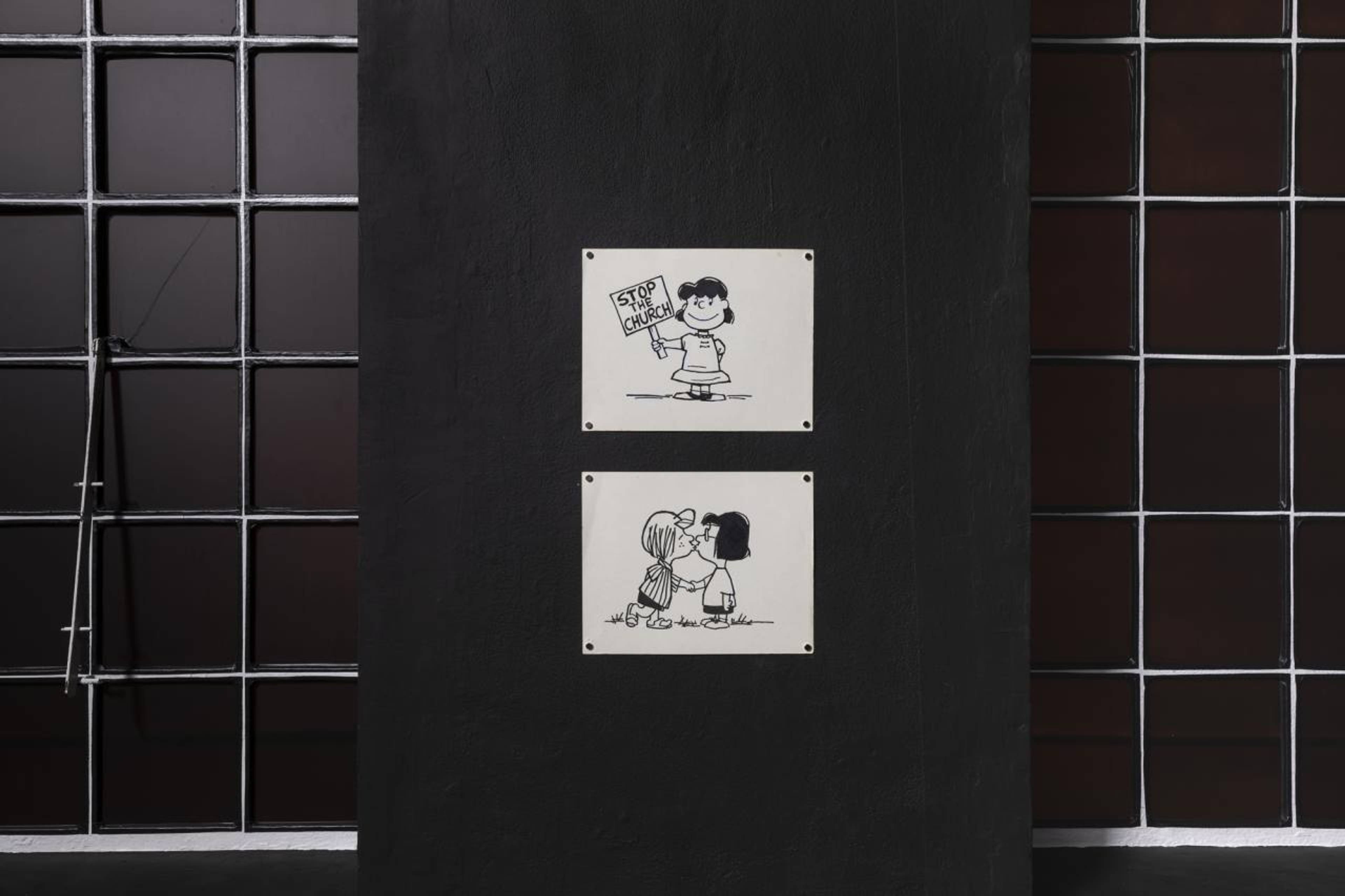

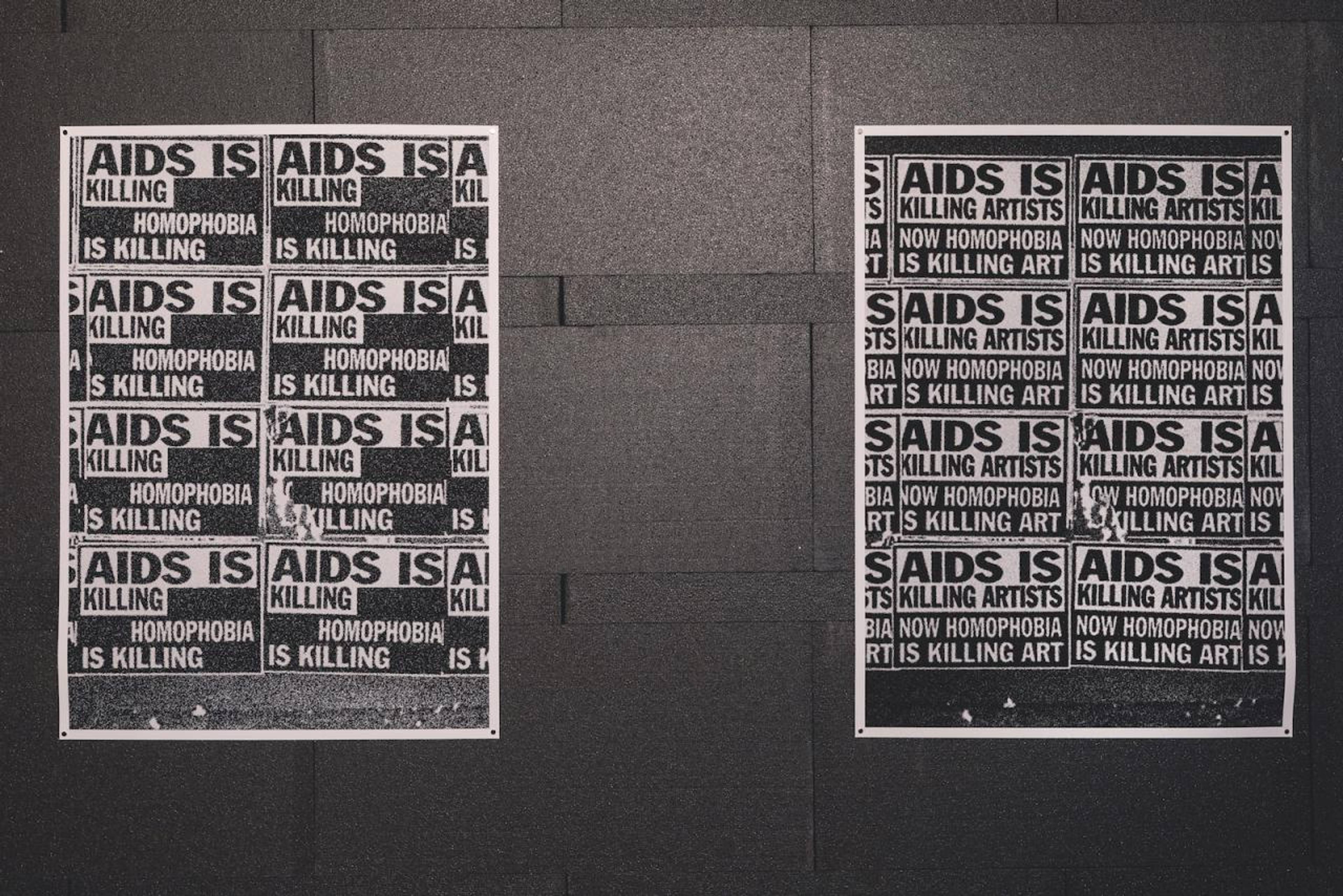

View of “Reframed Positions,” Halle für Kunst Lüneburg, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Halle für Kunst Lüneburg. Photo: Fred Dott

Terre Thaemlitz, Fuck Art, 2020, digital prints, 220 × 80 cm (each), reconstructed documentation of corrective graffiti on posters by Art Positive in New York City, ca. 1989. Courtesy: the artist and Halle für Kunst Lüneburg, Photo: Fred Dott.

___

“Reframed Positions”

Halle für Kunst Lüneburg

11 May – 16 Jul 2023