Included in “Intertwined,” Wangechi Mutu’s (*1972) expansive mid-career survey at New York’s New Museum, is a sculpture she made when she was still a student. Maria (1997) features a Black doll’s head resting precariously atop a souvenir statue of the Virgin Mary, with a gash in its forehead and cowrie shells for eyes. The early work showcases Mutu’s intuitive command of found objects, whose allegorical context she rigorously assesses and playfully remixes into a fusion of religious, Pop, and Afrofuturist stylings. Throughout “Intertwined,” there’s a sense of effortlessness to Mutu’s critique of Western culture’s most basic signifiers, as though the artist could instantly détourn and refashion the most anodyne of objects into totems.

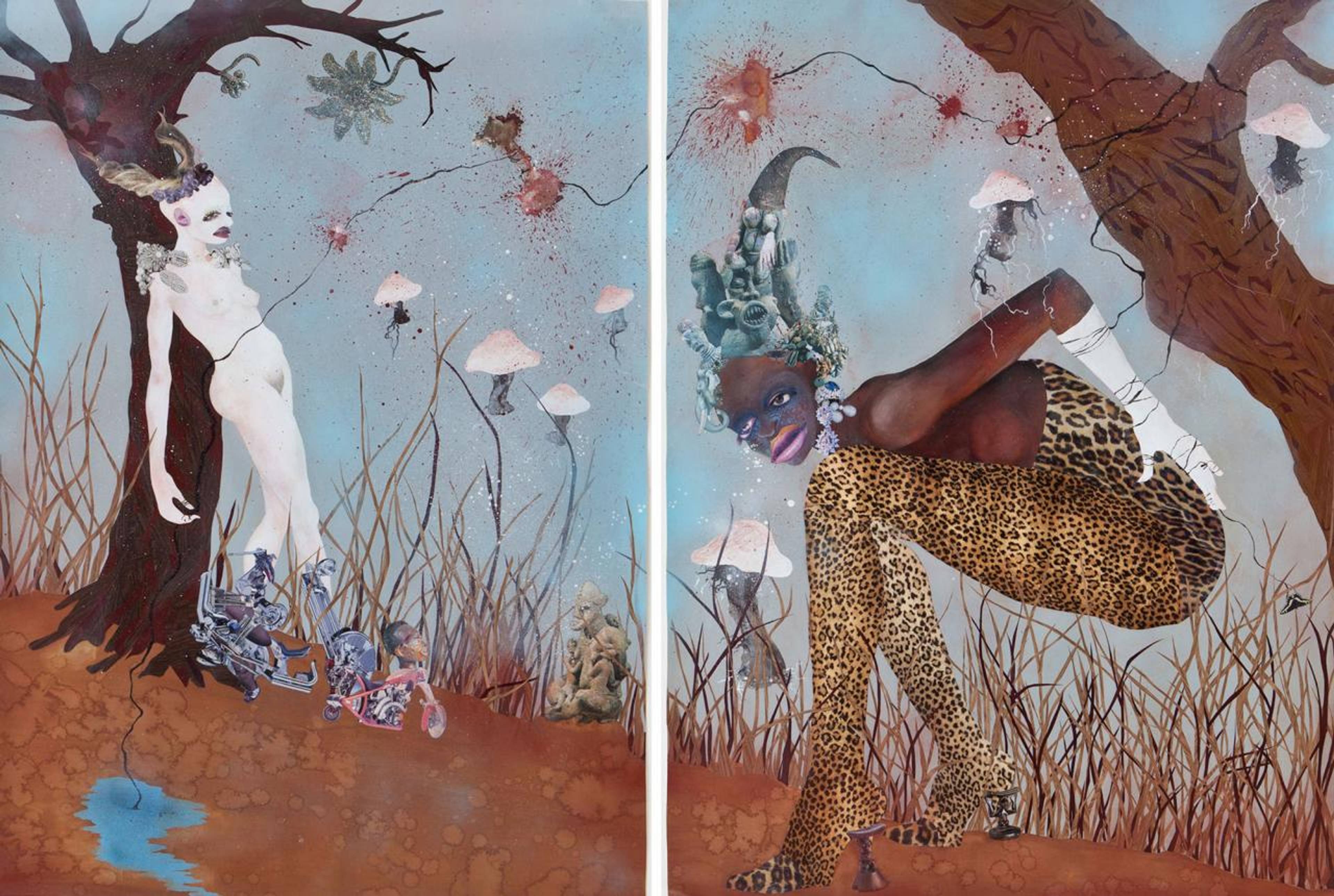

Because the most impressive works in this show are sculptures, it’s all the more remarkable to learn that Mutu first made her name as a print-media collagist. One of her earliest series explores the female form through cut-outs of exotic animals. Another, “Pin-Up” (2001), pastes the oversized features of American and European models onto watercolor Black bodies, often with glaring amputations – a reference to the civil war in Sierra Leone (1991–2002) that left many women there disfigured.

Wangechi Mutu, Maria, 1997. Plastic, string, paint, shells, and found object, 27.5 x 11.5 x 10 cm. Courtesy: the artist

A critique of mass culture through cut-ups feels obvious. But reducing Mutu’s collages to their polemical aspects ignores the imaginative strangeness of all her best work. Cutouts of body parts counterintuitively figure into bombastic, oddly alluring grotesques of tendril and flesh. Even when the artist is pasting women’s faces onto medical diagrams of uterine tumors, it never comes across as merely a political statement; rather, formal seduction outshines all sense of conceit, a feeling that only grows as Mutu’s collages increase in size and material variety.

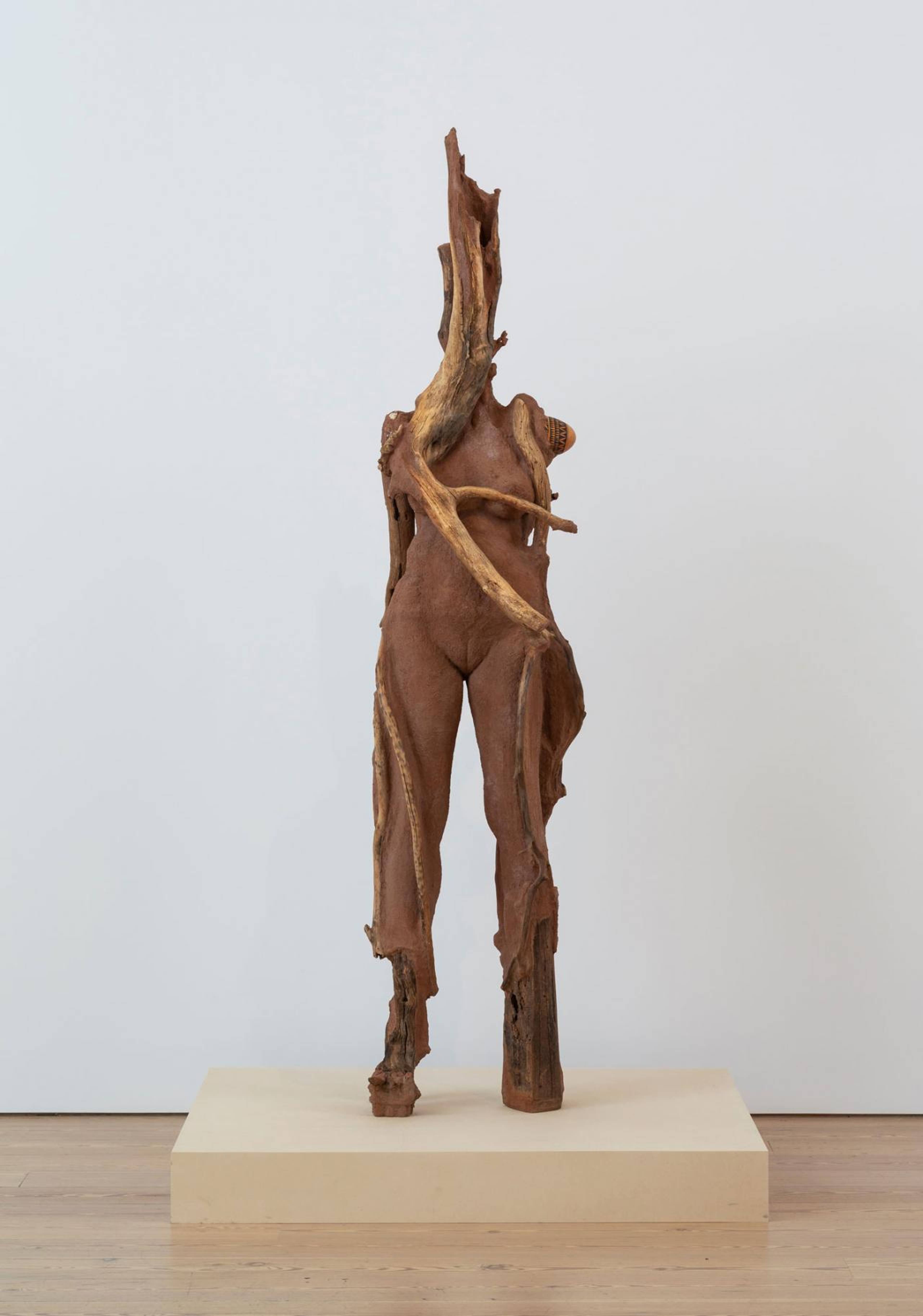

As a retrospective, “Intertwined” is unusually coherent, because Mutu approaches sculpture as another form of collage. Found objects feature intuitively throughout her wood-and-earth works: imposing, shamanic figures formed of dead branches and embellished with roan dirt from Kenya. The figures of “Sentinel” (2018–), alien yet convincingly human, take abstracted forms reminiscent of Giacometti but get there more happenstantially, doubling as realistic extractions of the landscape placed upright.

Wangechi Mutu, Sentinel I, 2018, red soil, pulp, wood glue, concrete, wood, glass beads, stone, rose quartz, gourd, and jewelry, 221.5 x 50 x 56 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Victoria Miro, London

I see an inflection point in her approach with The End of carrying All , a video project produced for the Venice Biennale in 2015. With the aid of VFX, Mutu moonlights as a National Geographic -esque stereotype of sub-Saharan African womanhood, carrying an oversized basket on her head. The basket progressively swells to include the silhouette of a smoldering city – a parable of resource extraction that climaxes with the woman getting encased in ectoplasm and sliding off a cliff. Taken together, the film’s allegorical obviousness and awkward graphics strike me as a turn toward symbolic over material resonance; in her breakthrough sculpture, the two were always combined, because found objects come with their own histories and politics.

The inert bronze sculptures Mutu has since turned to, which take up two floors of “Intertwined,” are, ironically, the work she is now most famous for – her hard-won career as a collagist abandoned for the easily iterable fabrication the market requires. The museum tries to claim the bronzes as yet another type of collage, with pastiches of form instead of material. Indeed, Crocodylus (2020), a large bronze of an alien figure fused to a crocodile, references a shot of Naomi Campbell from Harper’s Bazaar . Regardless of its source, there is no longer a sense that her work is conversing with or critiquing the world around it; rather, it has risen with its artist to the status of the commissionable – which is to say, the broadly palatable.

Still from Wangechi Mutu, The End of carrying All, 2015, 3-channel animated video, color, and sound, 10:45 min. Courtesy: the artist; Gladstone Gallery, New York, Brussels, and Seoul; Victoria Miro, London; and Vielmetter Los Angeles

What’s wrong with this? I was torn, as I passed through Mutu’s recent work, between elation that a brilliant artist has been recognized as such and dismay at the way this recognition undercuts the central thrust of her perspective as a subaltern. Coextant with this landmark retrospective, she is participating in the 15th Sharjah Biennial, while identical versions of Crocodylus are also on view at Storm King Art Center and the New Orleans Museum of Art. Shiny, itinerant, and divorced of specificity, her new work resembles currency in the way her earlier totems enshrine an aesthetics of poverty.

The success of “Intertwined,” which takes up more space than the New Museum has ever previously devoted to a single living artist, feels significant, even radical – just like when the Met used Mutu’s sculpture series “The Seated Ones” (2019) for their first-ever façade commission. Her work is the new instrument of choice for breaking ground; the price of hegemony is homogenization. If you’re one of these museums, the lesson here is straightforward and comfortably triumphant. If you’re a visitor skeptical of institutional power, perhaps in the very lineage of Mutu’s aesthetics of poverty, it’s reason to mourn. Sooner or later, her work will be cut out of glossy magazines and pasted into a new collagist’s critique.

View of “Intertwined,” New Museum, New York, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni

Wangechi Mutu, People in Glass Towers Should Not Imagine Us, 2003, mixed media collage on paper, diptych, 355.5 x 259 cm. Courtesy the artist

___

“Intertwined”

The New Museum

2 Mar – 4 Jun 2023