Things, which are seen, were not made of things that do appear.

The word: It fashions life about us as we, with our inner conversations, fashion life within ourselves; it’s the word that lifts us off the bar of the senses. The word drives our visual apparatus in constructing levels of reality and understanding, where the sensual, the concrete, and the allegorical meet. To shape is to form, with the spring of action directing forth all that is to become. “Objective reality,” wrote the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “is solely produced through imagination.” This, in a nutshell, is contemporary art: fables of varying intensities, driven by the need to say, to reveal, to covertly imply. Objects seem so independent of our perception that we tend to forget that they owe their origin to imagination.

So it is that “untold narratives” drive the thematic framework of Vienna’s Curated by festival 2024. With concept comes derring-do; thresholds and boundaries get crossed. In all of its digressions of unsung anti-heroes, heroines, outsider notions, and fanciful dramas, one can interpret the mythological depths in which narrative psychologically motors the residue of memory. A Joycean stream of consciousness pervading the whole, it is to myth that we must look in its infinite plots and dramas and situations – for we are not on the journey to save the world, but to save ourselves.

That poetry is a vital part of contemporary art cannot be denied. And since this festival’s edifice is built upon the cornerstone of the word, its visual cues must begin at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, where the late John Giorno (1936–2019) takes center stage. In “God Complex,” curated by the non-profit Giorno Poetry Systems, his life’s postscript is summa cum laude, concretely built in poem-paintings on aphoristic hubris. Some of the bright, candy-color schemes in his oeuvre stem from his Buddhist leanings; hence, the show’s bittersweet ironies, which lift the veil on his dreams, taboos, illusions, cynicism, and, ultimately, hope. You Got to Burn to Shine (2018) erupts its pithy messaging in big blocks of typeface that radiate like a 1000-watt bulb, while the bold axioms of the black and white paintings Filling What is Empty, Emptying What is Full (2015) and I Resigned Myself to Being Here (2012) leave a mental impression as large as a crater. Pick up the old-style rotary and push-button phones on pedestals for his signature dial-a-poem – and find yourself participant in a game of chance.

Views of John Giorno, “God Complex,” curated by Giorno Poetry Systems, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Vienna, 2024. © John Giorno Foundation. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / Vienna. Photo: Jorit Aust

With curating as a superstructure, “untold narratives” has its share of tangential subplots. Witness “A PALACE WITH NO ROOF,” curated by Giorno’s life partner, the über artist Ugo Rondinone, at Galerie Krobath. Snugly installed in the mid-sized space are ten works by the cultish painter David Deutsch (*1943), all new, untitled etudes of spontaneous combustion, big and brash, subtle and demure. Deutsch reverse-engineers painting by using a print method to extract sequential images from the polyethelyne support he’s painted on, which are then pressed and squeegeed onto linen – original and facsimile in one. The lines are painted fast and loose in burnt sienna, transferred to uniformly large formats on a cool white ground. A central figure stands isolated on a kind of proscenuim stage, dancing into being from the nothingness of the ground, a palpable vortex of energy framed and enlivened by architectural scaffolding. The crush of compressed space and the overlapping lines of demarcation ring Art Brut, but it takes a seasoned pro to work such naiveté to perfection.

View of David Deutsch, “A Palace With No Roof,” curated by Ugo Rondinone, Galerie Krobath, Vienna, 2024. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Rudolf Strobl

Visionary artists make art as a bulwark against despondency, their imagos straining in the mania of hermetic visions. At Croy Nielsen’s “OTHERWHEN,” co-curated by Luca Lo Pinto and Chiara Siravo, vintage assemblage works by Giuseppe Desiato (1935–2024) are rich in the artist’s peculiar byways, spookily like a midnight cemetery stroll. In four reliquaries (all Ex Voto, 1966/1975), idealized femme personas smart with melancholia, fish-eyed and freeze-dried into sculptural form. Loose, gossamer materials about the borders crop the interiors of their glass cases close, while crinkly plastic wrap and photo media mark formal transitions of space inside the frames. Monkishly devoted, Desiato raised the bar of reality in his coded obfuscations of interior conversations, equal turns Pop and photographically dissolute paens to the glamour of a vanished epoch. In tandem, the floor sculptures of Gianna Surangkanjanajai (*1991) truly impress. Four long, thick acrylic rods filled and sealed with monochrome paint (all untitled, 2024) whimsically ascribe food colors to the painter’s palate (as much as to her palette). Ketchup-red, mayo-cream, mustard-yellow, and relish-green look yummy in their brawny fineness. She has her minimalist cake and eats it too, marrying the blunt punkt of Blinky Palermo to the finesse of Walter De Maria. Breaching the visual mnemonics of sculpture and painting, their material refinement and formal beauty are as expansive as they are astute.

View of “OTHERWHEN,” curated by Luca Lo Pinto and Chiara Siravo, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2024

Giuseppe Desiato, Ex Voto, 1966/1975, assemblage on board, wooden box, glass, 83 × 63 × 12 cm. Both courtesy: the artists and Croy Nielsen, Vienna. Photos: Kunst-dokumentation.com

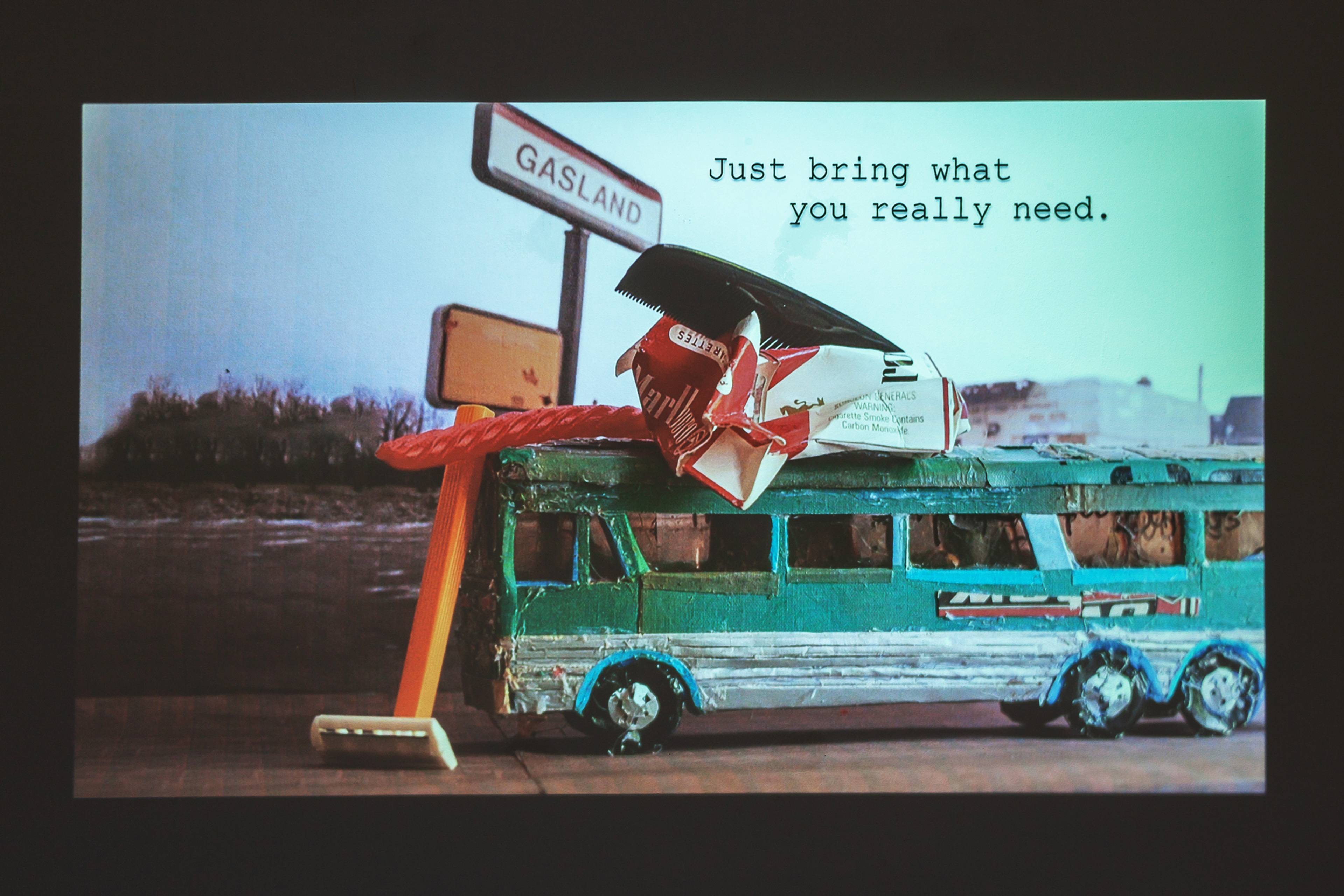

The Platonic axiom that the unexamined life is not worth living comes fully to light in the exhibition “You Don’t Go Anywhere” at VIN VIN, curated by Eleonora Milani (with exhibition design by Martin Hotter). Thirty-one small-scale bricolage sculptures placed on suspended wire shelves intimate the self-introspection of artist Lydia Ricci (*1973). Sticker-like glued components are molded into everyday things – toy cars, dollhouse furniture, a washing machine, electric appliances. Everything has outsider precociousness, and the raw edge of the scraps of detritus used to make them is Arte Povera all the way. Underscoring the install are exclamations and titles handwritten in pencil: Thinking About Listening (2019), They’ll All Be Here Again (2023), and We Should’ve Taken Better Care of It (2023) all point to estrangement and melancholy. Lifting the lid of her psyche, her worlds in miniature have a resignation about them. The sculptures even take on animate life in the stop-motion video The Letdown (2024), cinching by proxy the slo-mo feel of a person trapped in everyday banalities. Lugubrious and poignant, the Ricci storyline reminds me of Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable (1953): “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

View of Lydia Ricci, “You Don’t Go Anywhere,” curated by Eleonora Milani, Vin Vin, Vienna, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and VIN VIN Vienna/Naples. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

Still from Lydia Ricci, The Letdown, 2024, stop-motion animation, 3:48 min. Courtesy: the artist and VIN VIN Vienna/Naples Photo: Flavio Palasciano

Its often said that artists reveal the wounds of their soul. See: Ketty La Rocca (1938–76), who blasted the trumpet of doubt in her text-laden, mixed-media works, fraught with misgivings in the acts of life. Her restless way was an oblique and slippery commentary on the image-making mass media of her day. It’s those same mechanisms that drive the visual clues and repetitions of the exhibition “You You,” curated by writer Kate Sutton at Lombardi–Kargl. The title points to La Rocca’s ten-part series of ink drawings and photocopies, whose gestural repetitions and variations suggest a disembodied figure lurking in the shadows – phantoms Sutton played with to great effect. The big archival pigment prints of Tenzing Dakpa’s (*1985) series “The Hotel” (2016) are truly weird: Cryptic photos of pillows in his family’s hotel in Sikkem, India, their lumpen shapes ephemeral portraits of the bodies of recently departed guests. Repetition recurs in Under Falls of Air (2022), a spray-painted abstraction by Gabriele Beveridge (*1985). Repurposed industrial shelves are wall-mounted in ziggurat formation, their airy, soft gradation radiating a cool, calming mist. Lastly, two small wall sculptures (both untitled, 2024) by David Fesl (*1995) are combines in the vein of Richard Tuttle: little witticisms of fragments, material odds and ends that add up to a pictographic formality with shrewd economies of space.

View of “You You,” curated by Kate Sutton, Lombardi—Kargl, Vienna, 2024. © Lombardi—Kargl. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

Tenzing Dakpa, Pillow 02 (left) and Pillow 03 (right), from the series “The Hotel,” 2016. Installation view, Lombardi—Kargl, Vienna, 2024

Objects, to be perceived, must in some manner first penetrate our brains; what makes a present sense impression so objectively real is William Blake’s golden rule of art: “That the more distinct, sharp, and wirey the bounding line, the more perfect the work of art, and the less keen and sharp, the greater is the evidence of weak imitation.” That Blakean axiom came to mind when viewing the exhibition “Spine” at Gianni Manhattan, curated by Madeleine Planeix-Crocker. I hadn’t known the fiery, visceral works of Alison Flora (*1992), who paints delicate washes on paper in her own blood and frames them in rebars. Brutal and affecting, they’re searing infernals of another realm. Passage en écho (2021) and Dans le ventre de la terre (In the Belly of the Earth, 2023) float flickering, shadowy forms and figures across inky Goya browns and blacks. In medieval woodcut fashion, Flora speaks a bewitching, fabulist language. It’s in such fables that folklore leads to myth, and where superstition feeds the overloaded imagination.

View of “Spine,” curated by Madeleine Planeix-Crocker, GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna, 2024. Courtesy: the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna. Photo: Kunst-dokumentation.com

Work by Alison Fiona

As for the more prosaic chapter of Vienna’s art story: The commercial season began just as the long summer heat turned into blustery winds and furies of rain. It rained, and rained, and rained. Across the city’s three concurrent fairs – viennacontemporary, Parallel, and PARTICOLARE – business wasn’t so much soft as it was soggy, though the proceedings were lent an air of camaraderie by the laudable, spontaneous organization of shuttles between the former and latter Messen on their last, wet day.

Overhead view of viennacontemporary, Messe Wien, Halle D, Vienna, 2024. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

One of the better overall booths at viennacontemporary was Galerie Martin Janda’s, with a sublime painting by the protean artist Hugo Canoilas (*1977). The mid-size vertical Spiral Ascending (2024) looks like a meteor shower curling in the crepuscular sky. Werner Feiersinger’s (*1966) consistency often goes under the radar; here, a sweet pair of black steel floor sculptures (both untitled, 2022) have a bespoke understanding of volumetric space with the precision of Donald Judd, tempered by hand-made earthiness. A Fence into a Fence (2022), a sparkling, wall-mounted sculpture by Tania Pérez Córdova (*1979), is a fragment recast, hard in its metal structure and soft in the plume of the feathers tucked into its glittery pocket.

Hugo Canoilas, Spiral Ascending, 2024, high fluid acrylic on cotton, 150 x 110 cm. Courtesy: Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna. Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez, kunstdokumentation.com

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled (detail), 2002, steel, varnish, 40 x 26 x 60 cm. Photo: Galerie Martin Janda

Tania Pérez Córdova, A Fence into a Fence 1, 2022, aluminium, feathers, clay, (fragment of a fence that was cast, melted, and recast into its own mold), 97 x 77 x 3 cm. Photo: Gerardo Landa and Eduardo López (GLR Estudio)

Galerie Krinzinger had the golden touch with roster newcomer Toni Schmale (*1980). Following her star turn in the Belvedere Museum’s outdoor sculpture show, Krinzinger showed a recent steel sculpture, sucker #5 (2023), based on an industrial vacuum cleaner. Meanwhile, discreetly placed across the booth was Walter Pichler’s (1936–2012) Modell für den Kleinen Rumpf (Model for a Small Torso, 1994), the meticulous wood and clay sculpture a modestly sized talisman mounted atop a pedestal.

Toni Schmale, sucker #5, 2023, hot-galvanized steel, 125 x 60 x 97 cm. © Toni Schmale / Bildrecht Wien, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna. Photo: Katrin Binner/ basis e.V. Frankfurt

Walter Pichler, Modell für den Kleinen Rumpf, 1994, wood, loam, 36 x 18 x 22 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna. Photo: Carmen Alber

Meyer*Kainer showed Flora Hauser (*1992) coming into her own, her new works on canvas rife with the same obsessive minutiae as her pencil works, only this time with filigrees of yarn on variously sized linens. Detailed and mental, they are vivid with color and elaborate, as though influenced by miniatures of Hindu mythological deities.

Flora Hauser, Geburt der Sonne (Birth of the Sun), 2024, acrylic yarn and cotton yarn sewn on canvas, 210 x 100 cm. Courtesy: Courtesy MEYER*KAINER, Vienna

With a curatorial sensibility, E X I L E presented a solo by Kerstin von Gabain (*1979), whose sculptural installation included rotten apple (2024), a pessimistic neon sign laid out on straw a in wooden box on the floor, and a pair of Wächter (Watchmen, 2024), large obelisks that bely their lightweight material (cardboard). A hole and wooden perch dangling a pink rubber band from each confirm the sculptures elaborated birdhouses, while the low-placed black monochrome void of Fenster (Window, 2023) suggests an aperture in a medieval tower.

House of Spouse presented Georg Thanner’s (*1991) pungent and ecstatic paintings. They are as strange as Alexej von Jawlensky geometries in the excellent way the faces melt into the pastel-y ground patterns on the small-scale canvases, the madcap Condo-esques vibrating with surface nuances.

Works by Kerstin von Gabain at E X I L E, viennacontemporary, 2024

Works by Georg Thanner at House of Spouse, viennacontemporary, 2024

One can always rely on the fair model to supply both new and historicized painting, no less so in viennacontemporary’s Zone 1 and Context sections, curated respectively by Bruno Mokross and Pernilla Holmes. On the whole, theirs were spot-on contributions. W&K Wienerroither & Kohlbacher presented Max Weiler (1910–2010), among the last of a generation of dreamy Austrian romantics painting ellipses of abstractions that leaned towards landscape. He looked fresh just around the corner from the brash, young, Krebberesque Albert Dietrich (*1997), who killed it at City Galerie wien with an ebullient mix of loose blots, scribbles, and stains. These he combined with deft sculptural latitude, placing found wooden shelves on pedestals all along the wall to frame the whole install as a snug den. An insouciant air of total freedom reigned.

Works by Max Weiler at W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher, viennacontemporary, 2024

Works by Albert Dietrich at City Galerie, Wien, viennacontemporary, 2024

Wandering off in search of the unknown, I discovered the tautological paintings of Kosara Bokšan (1925–2009) in a solo presentation at the Serbian gallery Rima. Embedded with figuration, her abstractions (here from the mid 60s to 80’s) are old school: Adolph Gottleib meets Howard Hodgkin, with gentle waves of color sprouting fluidly from one another.

Kosara Bokšan, Icarus, 1973, combined technique on canvas, 97 x 130 cm. Courtesy: Galerija RIMA, Belgrade / Kragujevac

Kosara Bokšan, Women-Mountains, 1989, oil on canvs, 130 x 195 cm. Courtesy: Galerija RIMA, Belgrade / Kragujevac

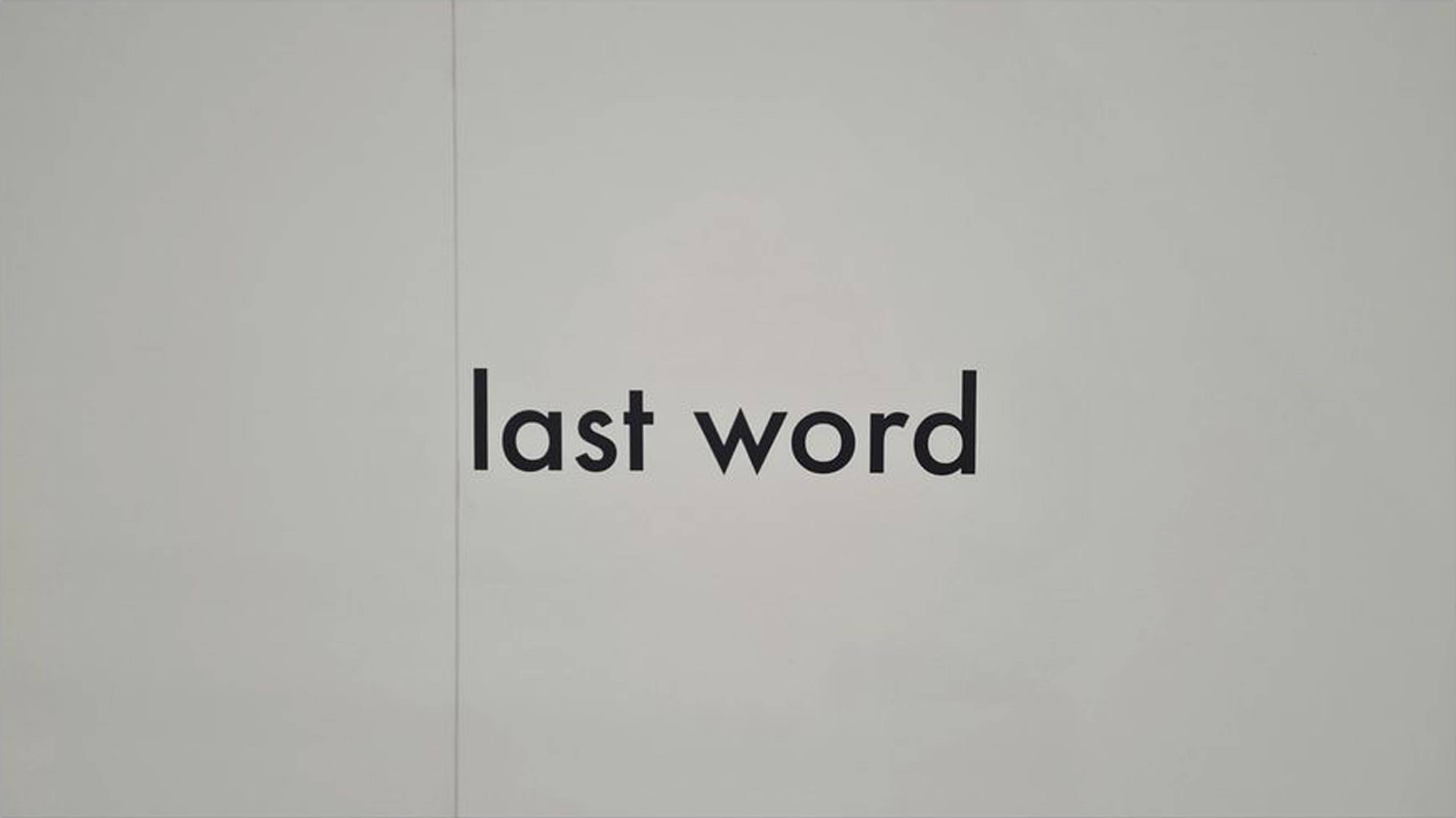

Lastly, Anna Ebner-Quadri’s and the editions booth located gaps in the multiples market with a great eye for conceptual wit and concrete poetry, such as framed text pieces by Jiří Valoch (*1946). Graphic with the tip-tap of the typewriter, the poems are material remnants of thoughts “sculpturally” enriched in multiple-page layouts. Modern-day papyruses, one day in the far off future they will turn to dust. Yet the sentiment remains born to poets of every age that the lost word is the last word.

Jiři Valoch, last word, 2022/24, vinyl letters, dimensions variable. Ed 30 + 3 AP

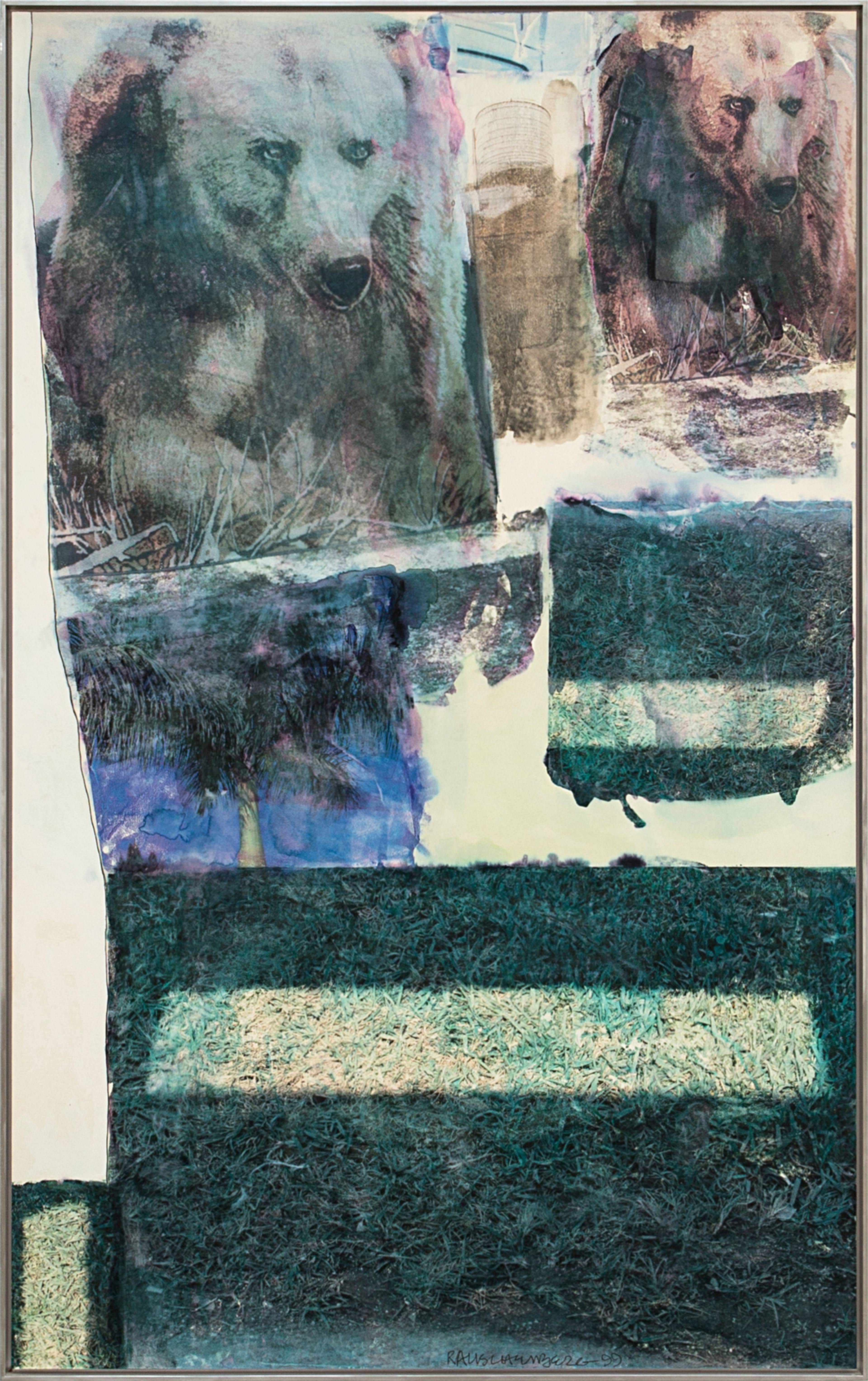

Overall, though, more gallery participants in this year’s fair (up from sixty-one to ninety-eight) didn’t necessarily make for a better experience. The general layout – cramped in some parts, vast and blank in others – felt like a dreary airport. The flimsy walls, droopy VIP lounge, and eyesore of a McCafe-style cantina made obvious a paucity of investment in basic infrastructure. Every gallery shelling out money for the booths and their artists deserves a higher standard, not to mention that it’s conducive to good business to provide an aesthetic, somatic comfort to clientele potentially shelling out 500k USD for a classy late Robert Rauschenberg, whose Bear Grass (1999) looked more like a million bucks at Thaddeus Ropac. (And why were the publications, which contribute so much to the overall game, left out on the outer perimeter of the fair? There was plenty of space to incorporate them seamlessly into the mix, as some also carry with them really good editions from star artists.) There’s no dearth in the talent pool, and fixing these issues ultimately just means helping the best of the art on view to prevail.

Robert Rauschenberg, Bear Grass, 1999, inkjet pigment transfer and graphite on Polylaminate, 247.7 x 154.9 x 1 cm. © The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Bildrecht, Wien 2024. Courtesy: Thaddaeus Ropac

Traversing the rolling hills of the Otto Wagner Areal, a leafy complex of historic buildings west of central Vienna, all hell broke loose. Parallel’s cavernous home, a former medical clinic, is a madhouse, sensory overload and kitchen sink, puberty-4-ever; this despite the fair now running in its twelfth edition. Up high in the spacious entry room hung a buoyant new word painting by Nicolas Jasmin (*1967), Untitled, SHE BAROCK (2024), laid out is a blocky grid on raw canvas. In the middle of the space was Gelitin’s huge Democratic Sculpture 7 (2023), a bulky, twisted cloth form like a slice of pizza with toppings, which you can crawl beneath and poke your head through to become a part of the whole. Multiple heads looking and smiling luridly back. Sick. Absurd. I nearly peed in my pants with laughter, but had to march upstairs before a crush of people took over.

Nicolas Jasmin, Untitled (SHE BAROCK), 2024, laser-removed dispersion on raw canvas, 200 x 150 cm. Courtesy: the artist

Gelatin, DEMOCRATIC SCULPTURE 7, 2023. Installation view, Parallel, Otto Wagner Areal, Vienna, 2024. Photo: JollySchwarz

Epitomized by the performance of young boy dancing group, Parallel was messily filled with sparkle and flash. It’s fun to find a young painter who you know has it already. Room 209 hosted a group exhibition of the University of Arts, Linz, where Magdalena Maller’s (*1997) two egg tempera works on raw canvas were blunt and rich, their saturate colors having a mythic drama to them. One was hung loose, unstretched and strong in its rough hew. The future looks good there!

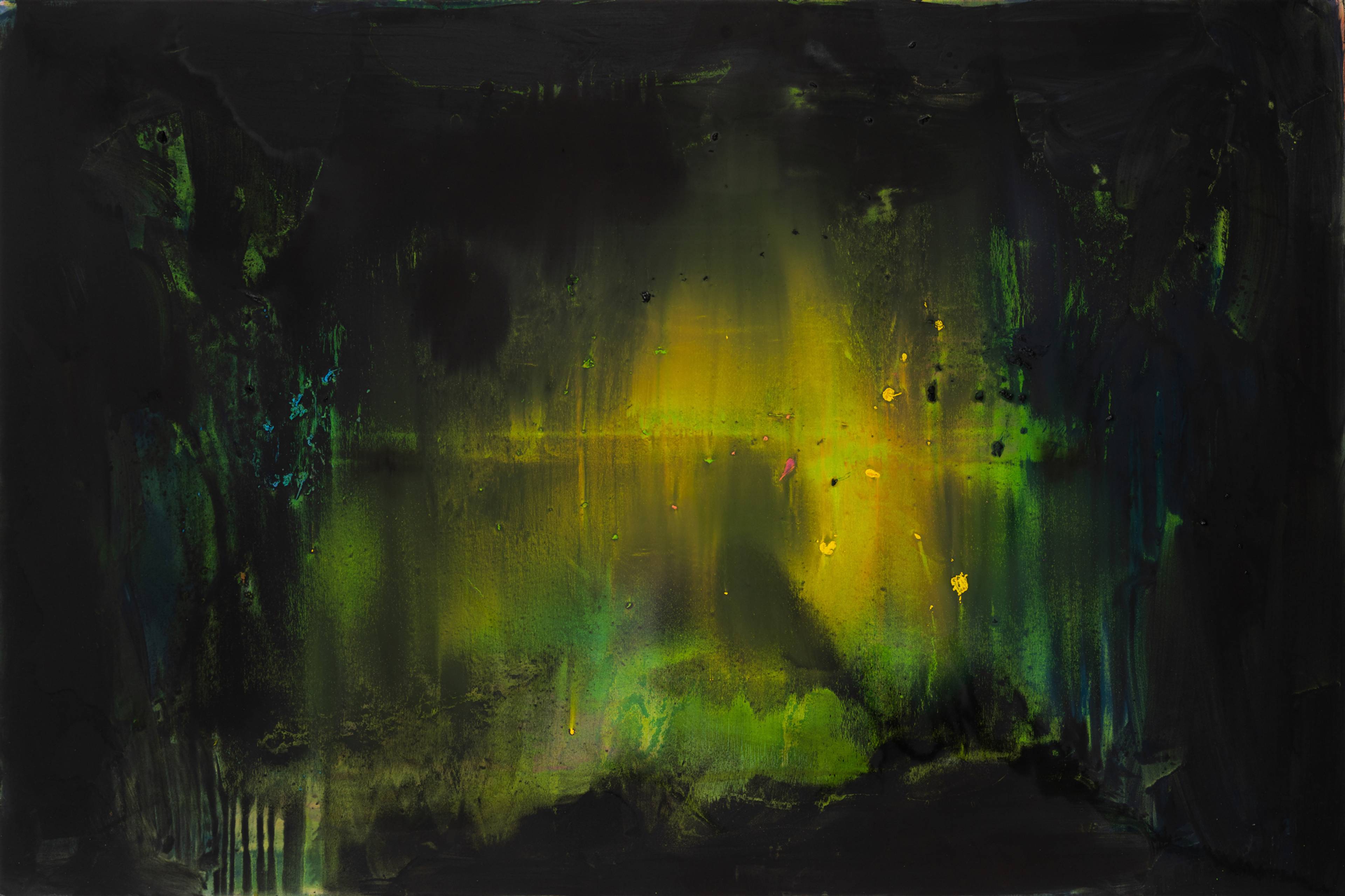

Down the hall, the cathartic output of Panos Papadopoulos (*1975) smoldered with the dark visages of a restless imagination. Gothic plumes of midnight-blues and -blacks offer no fixed points, only palimpsests of murky depths. Contemplating such nebulae has a way of humbling a man …

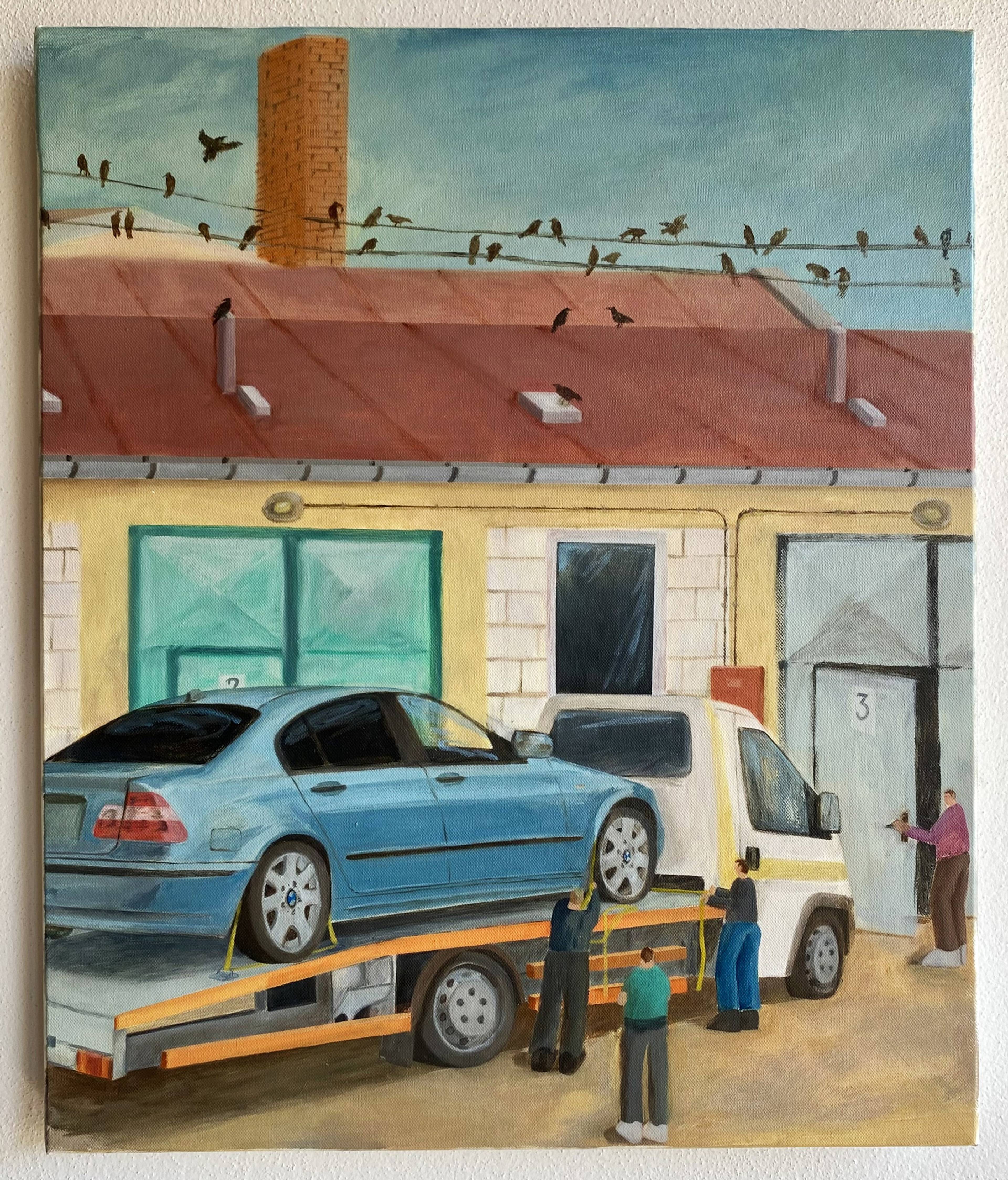

In a solo at C.A. Contemporary, Miroslav Pelák’s (*1992) subject matter in “Old Foundations, New Dream” (2024) was big-bodied men with small heads. Influenced by Mexican murals, Pop, and social realism, the Slovak painter romanticizes propagandistic dreams, turning yesterday’s nostalgias into witty outtakes of the everyday. Additionally, his fresh palette marks off masculinity and success with geometric boldness, playing giantism and reduction off each other. The he-men mollycoddle their bodies and cars, work out, admire their women, or go out on a date, knowing the frayed edges of life always get mellowed out during leisure time’s pursuit of luxury.

Magdalena Maller, ich weiß immer wie alt es wäre (i always know how old it would be), 2024, oil, pigment, and egg-tempera on canvas, stitched, 140 x 44 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Laura Weiss

Miroslav Pelák, Foreigners Everywhere, 2024, oil on canvas 50 x 60. Courtesy: Galerie C.A Contemporary, Vienna

Confronted with Galerie Krinzinger’s install of Bianca Kennedy’s (*1989) aggressive five-channel video ANGERS (2024) gave new meaning to histrionics through the use of appropriation. The room lit in emotion inducing red, excerpts from Hollywood films that were edited and condensed into interconnected scenes of actresses full-on raging at their viewers. A real horror show, I bolted the room agitated by its cringe-inducing manipulations. At last I found some peace and quiet outside taking it all in, decompressing amidst the smell of food carts wafting in the air.

Panos Papadopoulos, The great opening, n.d., oil on canvas, 140 x 210cm. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

Bianca Kennedy, ANGERS, 2024, five-channel video, 4:40 min. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna. Photo: Carmen Alber

On my way to the bar, I noticed upon a grassy knoll, a glistening apparition, subtle with undulating curves, and graceful personage – Joannis Avramidis’s (1921–2016) Figur 1 (Figure 1, 1984), a bronze totem silently watching the beehive proceedings below. After some inhalations, I went back inside knowing that there was still sanity in the madding world.

The sophomoric character of some statements made you wince and wrinkle your nose. But that’s what distinguishes Parallel – it’s an anarchistic hybrid of fair and happening. Its free-for-all attitude attracts a motley segment of the art world, looking for decadence with an edge. Ugliness aside, you have to find the needle in the haystack, room after room after room.

Theater, Parallel, Otto Wagner Areal, Vienna, 2024. Photo: Jolly Schwarz

Exterior view of Parallel, Otto Wagner Areal, Vienna, 2024. Photo: Claudio Farkasch

Out of the gray mist of thunderstorms, the collectible exhibition Particolare appeared at Kursalon, a 19th-century music hall in the 1st District. Here at last was a tight ship, sound in its concept and discerning in its curatorial vision and structural organization, with an open floor plan (as in Basel, Unlimited) amid intimate surroundings. Participation is by invitation and fee-free; the fair takes a 20% commission on sales. Less was more. Modeled after early 20th-century French salons, Particolare gave dignity back to the art viewing-experience, the fine oval ceilings and glittering chandeliers adding a dose of glamour. It was a connoisseur’s game there, grounded by the playfulness of the installation and tactful use of the space. Obviously, the game here is for “A” level works (though a couple fell short), benchmarked by the top-tier excellence of TEFAF, Maastricht. With a triumvirate of very experienced curators, you immediately sensed a different approach.

Far left: John Miller & Richard Hoeck, Living in a Hearse, 2009; center, foreground: Liesel Raff, Short Liaisons (tripod), 2022/2023. Installation view, PARTICOLARE, Kursalon, Vienna, 2024. © Particolare. Photo: Andrey Gordasevich

A circular entry/exit was divided by a wall projection of the arresting performance HIGGS, In Search of the Anti-Motti (2005), wherein Gianni Motti (*1958) followed with his own body a proton’s trajectory through CERN’s twenty-seven-kilometer-long particle accelerator. Moving around this prelude, the main hall was spaced with unexpected juxtapositions and strong sculptures. Rising star Liesl Raff (*1979) showed her bonafides with the totemic Short Liaisons (tripod) (2022/23). It soared towards the ceiling, trailing its natural rubber downwards into elegant curlicues of minimalist, color-coded stripes. To its right stood John Miller (*1954) and Richard Hoeck’s (*1965) Living in a Hearse (2009), a child mannequin dressed in biker gear and tattooed with the cave paintings at Lascaux – a punk gesture from long-time collaborators. A Joseph Kosuth (*1945) neon work, L.W.’s Last Words [Cobalt blue] Text reads: Sprache (1991), also drew me near, before I found my way to a darkened, enclosed space with the sound of whirring fans, where Žilvinas Kempinas’s (*1969) whimsical Flying Tape (2004) shifted my senses to more ephemeral things.

Stills from Gianni Motti, HIGGS, In Search of the Anti-Motti, 2005, performance documentation, LHC tunnel (particle accelerator), CERN, Geneva, 350 min. Courtesy: Galerie Mezzanin, Geneva

Joseph Kosuth, ‘L.W.’s Last Word’ [Cobalt blue] Text reads: Sprache, 1991, cobalt blue Neon, 75 x 245 cm. Courtesy: Christine König Galerie, Vienna

Alicja Kwade, Amáss, 2021, concrete, copper, 225 x 120 x 109 cm. © Alicja Kwade. Courtesy: the artist and Mennour, Paris. Photo: Roman März

Žilvinas Kempinas, Flying Tape, 2004. Installation view, PARTICOLARE, Kursalon, Vienna, 2024

Plamen Dejanoff, Foundation Requirements (Door), 2014, oak wood, 192.5 x 107 x 18 cm. Courtesy: Pinksummer Contemporary

Upstairs was a surprise: the sounds of a live piano player performing Erik Satie’s mournful composition Vexations (c. 1893–94). Its Dada touch was made all the more piquant by Alicja Kwade’s (*1979) show-stopping Amáss (2021), a twisted trombone embedded into concrete blocks (and priced at six figures). Installed altarpiece-style, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s (*1933) large-scale, three-panel Smartphone giovane donna 6 movimenti F (Smartphone young woman 6 movements F, 2018), showing a woman in three positions gazing at her screen with her back turned to the viewer, chimed with the surreptitious people-watching of art-viewing spaces. Rob Pruitt’s (*1964) new twenty-four panel painting May 17, 2024 (One Day) (2024) brought a burst of gradient color, conceptual rigor, and gravity (the title is his birthday), while an ornamental sculpture by Plamen Dejanoff (*1970), Foundation Requirements (Door) (2014), beautifully framed Pruitt’s eye-friendly palette in an elaborately carved wooden portal.

Particolare won out with a smart, ambitious format and lots of big-ticket names. Keeping in mind its three-month turnaround, one wonders what might take shape with more lead-time and wider promotion (my mentions of it met with many shrugs, then curiosity). New benchmarks have to be met in this dog-eat-dog carousel of art fairs and ancillary cultural events. A more productive future will come only of constructive criticism and investment in the long view, not from tiresome complaints about the state of things. For all the critiques of the art-fair model, or even late-capitalist antagonisms, it’s unprecedented that so many artists today are able to lead fruitful working lives in this leviathan of contemporary art. Let the cream rise to the top!

___

Curated by: “untold narratives”

Various galleries, Vienna

17 Sep – 19 Oct 2024

viennacontemporary

Messe Wien Halle D, Vienna

11 – 14 Sep 2024

PARTICOLARE

Kursalon, Vienna

11 – 15 Sep 2024

Parallel

Otto Wagner Areal, Vienna

21 – 22 Sep 2024

![Joseph Kosuth, ‘L.W.’s Last Word’ [Cobalt blue] Text reads: Sprache, 1991](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/syotmk9q/production/ea317f0517e4d000e13794e6cfccb7144aa192de-2000x1334.jpg?w=3840&h=2561&q=70&auto=format)