Ensconced within the vacuum-sealed environment of Stanislava Kovalcikova’s “Grotto” at Belvedere 21, the foibles and bubblegum novelties of the outside world are forsaken in favor of a temperature-controlled cocoon. The exhibition, whose structure usurps the white cube of the museum space, is named for the artificial grotto in Hugh Hefner’s infamous Playboy Mansion, known for its decadent opulence and dissolute orgies with all the trimmings. Etymologically, “grotto” brings with it the “grotesque” as much as it does the pastoral. This is important to note when puzzling over pictures that turn a classical notion of beauty on its animatronic head.

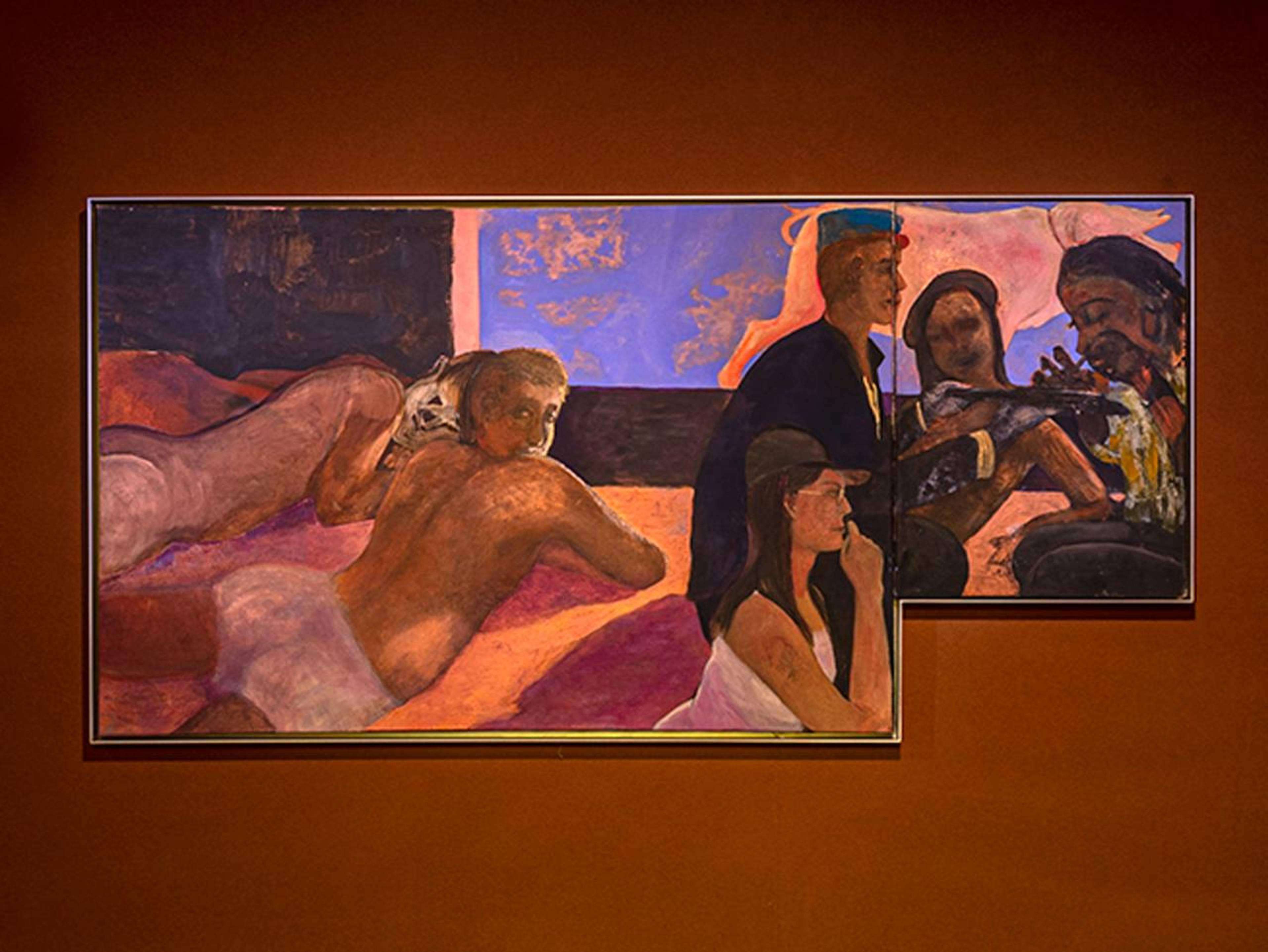

Kovalcikova’s strength in classical painting lies in her willingness to butcher its conventions, evident in the grotesqueness of her figuration. What pulls the viewer into the exhibition’s center of gravity and holds the attention is the felt-lined, grizzly-brown walls and floor, along with the fact that all of the pictures are hung in artist’s frames. Yet her images are not so much pastiches of precious art-historical citations (of Van Gogh and Gauguin predominantly) as they are conflations of their multi-century timelines, fluidly arranged with the wide-angle horizontality and compact verticality of a phone camera. As in religious altar painting, Kovalcikova’s frequent use of multiple panels accentuates the heightened, fragmentary nature of the narratives she depicts, pieced into a whole as though cut and pasted from screengrabs.

View of “Grotto,” Belvedere 21, Vienna, 2022

Kovalcikova is the mistress of her own moods and knows how to serve them. No twee little pictures. No insipid, flavor-of-the-month portraiture. No crowd-pleasing banalities. Just the scabrous encrustations of attrition. Motifs and patterns recur within each image, like checkered grids, landscapes, masks, and shadow forms with animal appendages, as blank and knowing faces stare back from the canvasses. How pallid are their skin tones, pink, brown, and black, redolent with Byzantine metallic colors streaked across flat and noisy grounds. Like her mentor, Peter Doig, she has arranged her mannerist figures just so, bringing forth lapses in past, present, and future tenses. The haunted visages have an affinity with Goya’s macabre specters and the geometry of medieval perspective. In life, a woman sometimes feels pity for the sorrows she has caused or received remorselessly – and she must have the courage to paint them.

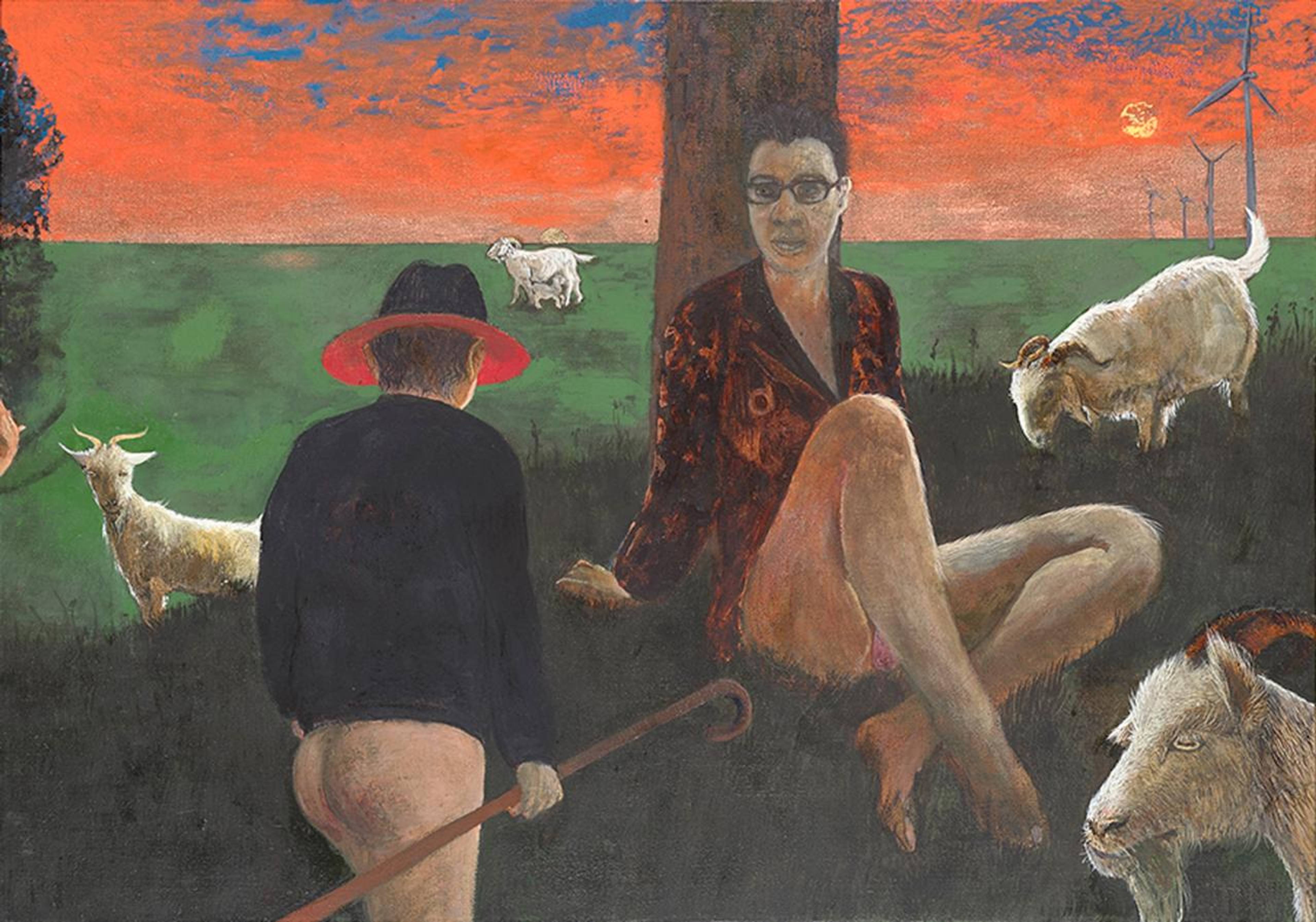

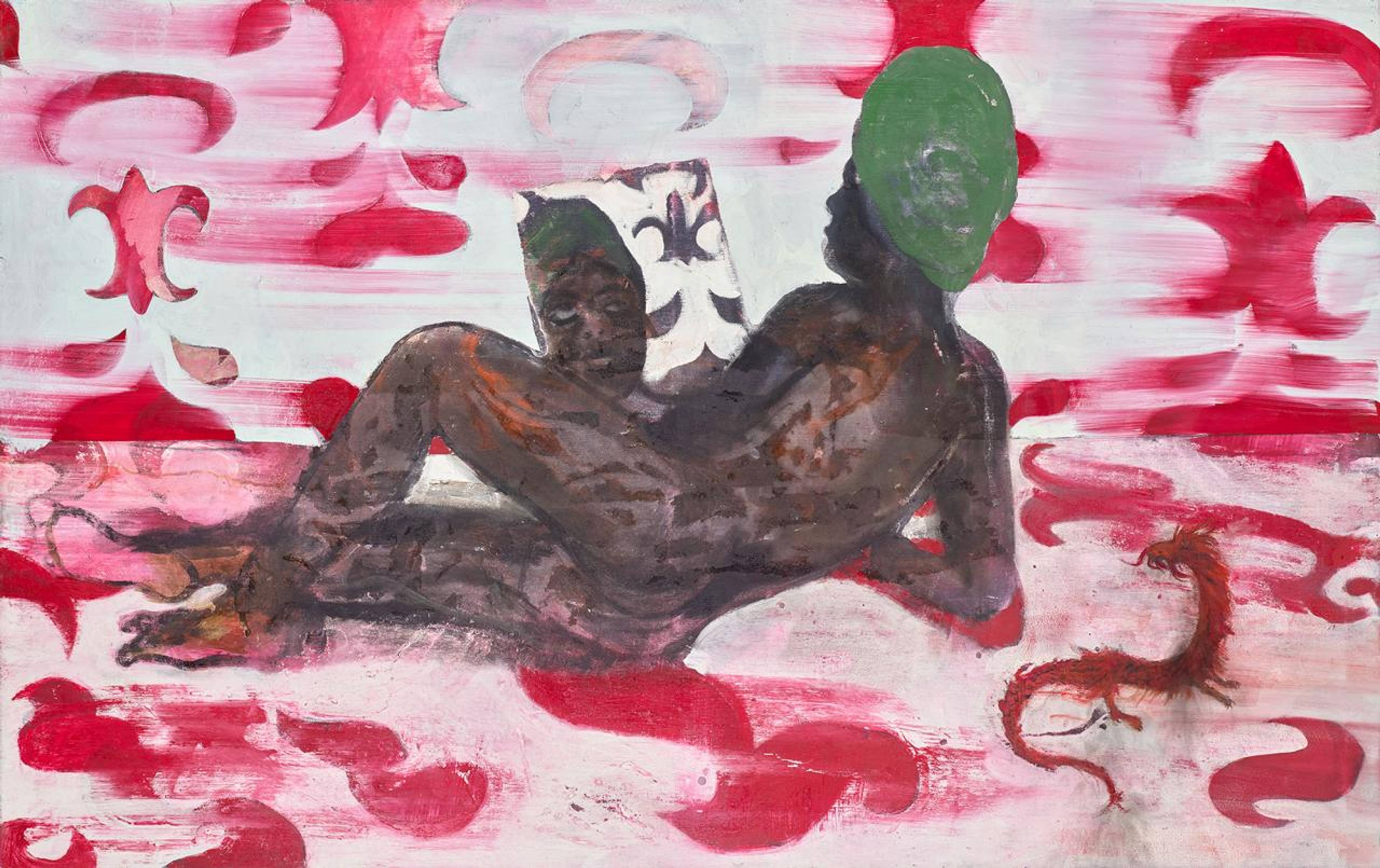

Note her use of panorama in the three-panel Die Gute Hirtin (The Good Shepherdess, 2022), a strange bacchanalia of gender-ambiguous and mostly nude figures that populate a landscape with goats and a faun. One ghastly figure wraps an arm around another, who wears a blue latex glove, while a third plays with its genitalia and a fourth wears a goat’s skull for a head; a seated figure at center looks out demurely at the viewer – the voyeur of that freakish pleasure dome. The burnt, orange-red sky and dingy, mottled grass could be Martian, but the picture’s nostalgia for Arcadia is as earthly as the scaled-down wind turbines slyly placed in the background. Nearby, the intriguing Double Venus (2019) shows a pair of big-bodied women in a near embrace, as overpainted faces mysteriously peek out of a mottled white ground. The large-format Sad Venus (2015–22), meanwhile, shows a naked, brown-skinned, green-turbaned persona staring into a hand mirror amid an atmospheric pattern of red symbols, alongside a small, red dragon.

Stanislava Kovalcikova, Die Gute Hirtin (The Good Shepherdess), 2022 (detail), oil on linen, 95 x 297 cm

Stanislava Kovalcikova’s tough love is a counteroffensive to the sterility of techno-objectification and the illustrative affectations of the Johnny-come-lately school of painting. Her anti-heroes reside in an airless netherworld between the living and the dead, gathered in the crucible of rekindled moments and Freudian dream spells. A tautology of split personalities peers through the earthy browns, Pompeian reds, Van Gogh greens, Gauguin ochres, and Mantegna plum-oranges, contrasting somber earth tones and vivid colors. Hers is figuration as palimpsest, the layers of paint like circadian testimonials or paeans to loves lost and loves won, child-bearing gravity, and the ecstasy of art-historical constructs, role play, and fantasy.

When painters steal fire, they can get burned by the kitsch of postmodern sampling. But Kovalcikova’s thefts are up to the task of encrypting an increasingly bizarre contemporary reality in a language of her own invention. If you can crack her Da Vinci codes and canonical grafts, you can recognize that the archetypes of painting are not bound by place or linear history. With such new corporeal mythologies, it’s the allegorical in painting that mines the depths of the present. All of the age-old questions have been asked time and again (who are we, where do we come from, where are we going), yet they remain riddles.

Stanislava Kovalcikova, Sad Venus, 2015–22, oil and foil on canvas, 95 x 150 cm

Henri Bergson said that behind every mental state lies a vast region of perceptions and correspondences that elude the image-making powers of surface consciousness. The more transcendent the perception, the less its image contrives to represent. Kovalcikova grasps that notion – in her paintings, it’s not what you see, but what you sense that counts. Despite the cheapening ubiquity of flat-screened media, what cannot be faked is the eternal life of the real, the art of memory in all of its carnal frisson.

View of “Grotto,” Belvedere 21, Vienna, 2022

Stanislava Kovalcikova, Wait till the sun shines, 2022, oil on linen, 100 x 205 cm

___

“Grotto”

Belvedere 21, Vienna

16 Sep 2022 – 5 Feb 2023