The press view for the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, “Though it’s dark, still I sing”, in Ibirapuera Park, was the third time I’ve seen Indigenous people play a prominent role at the opening of a major international exhibition. The first was in 2017, when documenta 14 in Athens was opened by German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier and former Greek president Prokopis Pavlopoulos admiring a collection of masks made by Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick, who’d passed away a few weeks beforehand. His masks were of characters like Bakwas, who tempts his victims with poisonous treats then robs them of their souls, and Dzunuk’wa, who likes to eat children. The second came later that summer, outside the Pavilion of the Shamans in the Giardini, Venice, where Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto collaborated with some Huni Kuin people on Um Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place), a hanging tented space for social events and ceremonies. During those balmy opening days by the lagoon, the Huni Kuin led conga lines through the crowds of dealers, curators and critics milling round the Giardini, like a scene from a Fellini film.

In São Paulo, four large, vivid canvases by Daiara Tukano, of the Uremiri Hãusiro Parameri clan of the Yepá Mahsã people, also called the Tukano, hang from the ceiling in a perfect square, facing inwards and backed with plumes of feathers. Inside they’re painted with psychedelic op-art patterns, reflecting her experiences of ayahuasca, and over those, four sacred powerful birds from the rainforest: a harpy eagle, a king vulture, a capped heron and a scarlet macaw. At the opening, in the exact centre of her square, Tukano sat on a handmade stool in full ceremonial dress giving an interview to a Brazilian TV crew that knelt around her, making a compelling tableau. She doesn’t consider her paintings to be artworks, in our Western sense, but rather messages about the plight of her people and ancestral homeland. She might be considered the face of this show.

Daiara Tukano interviewed in her installation Dabucuri no céu, 2021

Jaider Esbell, a Macuxi artist and organiser who has many works in the show and the park and has also curated an exhibition of indigenous artists next door at the Museum of Modern Art, might also. His brightly crowded, frantically layered series of paintings A guerra dos Kanaimés tells the story of the war of the kanaimés : bloodthirsty, malevolent chimeric spirits that dwell in the forest. The main exhibition also includes Sueli Maxakali, a leader of Brazil’s Tikmũ’ũn people, Abel Rodríguez, of the Colombian Nonuya, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Indian Nation in the United States, alongside plenty more artists who are of Indigenous descent, or make Indigenous culture their subject matter. Like many recent biennials, it’s a post-colonialist’s dream. But that feels most natural here, because we’re in Brazil.

I often wonder, looking at art today, “Where’s the blood on the wall? Where’s the glory and the dirt?” But here there is plenty.

The Bienal Pavilion, built by Oscar Niemeyer in 1957, is a long glass exhibition hall you can see from the plane, set in green parkland at the heart of the concrete skyscraper sprawl of São Paulo. It’s an appropriate site for an alternative history of modernity, which is one way of reading this edition of the Bienal, curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, Paulo Miyada, Carla Zaccagnini, Francesco Stocchi and Ruth Estévez.

Pierre Verger, untitled (Candomblé do Pai Cosme series), 1950. Fundação Pierre Verger

Nomadic French photographer and ethnographer Pierre Verger’s pictures from the 1940s and ’50s of initiations into the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé, of wavy-eyed participants slurping blood from the decapitated heads of rams, the bodies of headless chickens, or painted all over with spots like Kusama sculptures, provide a visceral highlight, and are more thoroughly contextualised in his accompanying retrospective at Instituto Tomie Ohtake. I often wonder, looking at art today, “Where’s the blood on the wall? Where’s the glory and the dirt?” But here there is plenty.

In an old interview reposted in his room at the pavilion, Verger speaks of how a few of these pictures were first published in Georges Bataille’s L’Érotisme (1957) and Les Larmes d’Eros (1961), somewhat against his will. He wasn’t much impressed by Bataille, whom he only knew by sight from Paris, but Bataille was of course delighted by his visions of decapitation and ecstasy. For a long time, he wouldn’t allow the rest of the photos shown here to be published. His subjects didn’t know they were being photographed, he said, for they were in a trance. Verger himself was later initiated as a Candomblé Babalawo , a diviner.

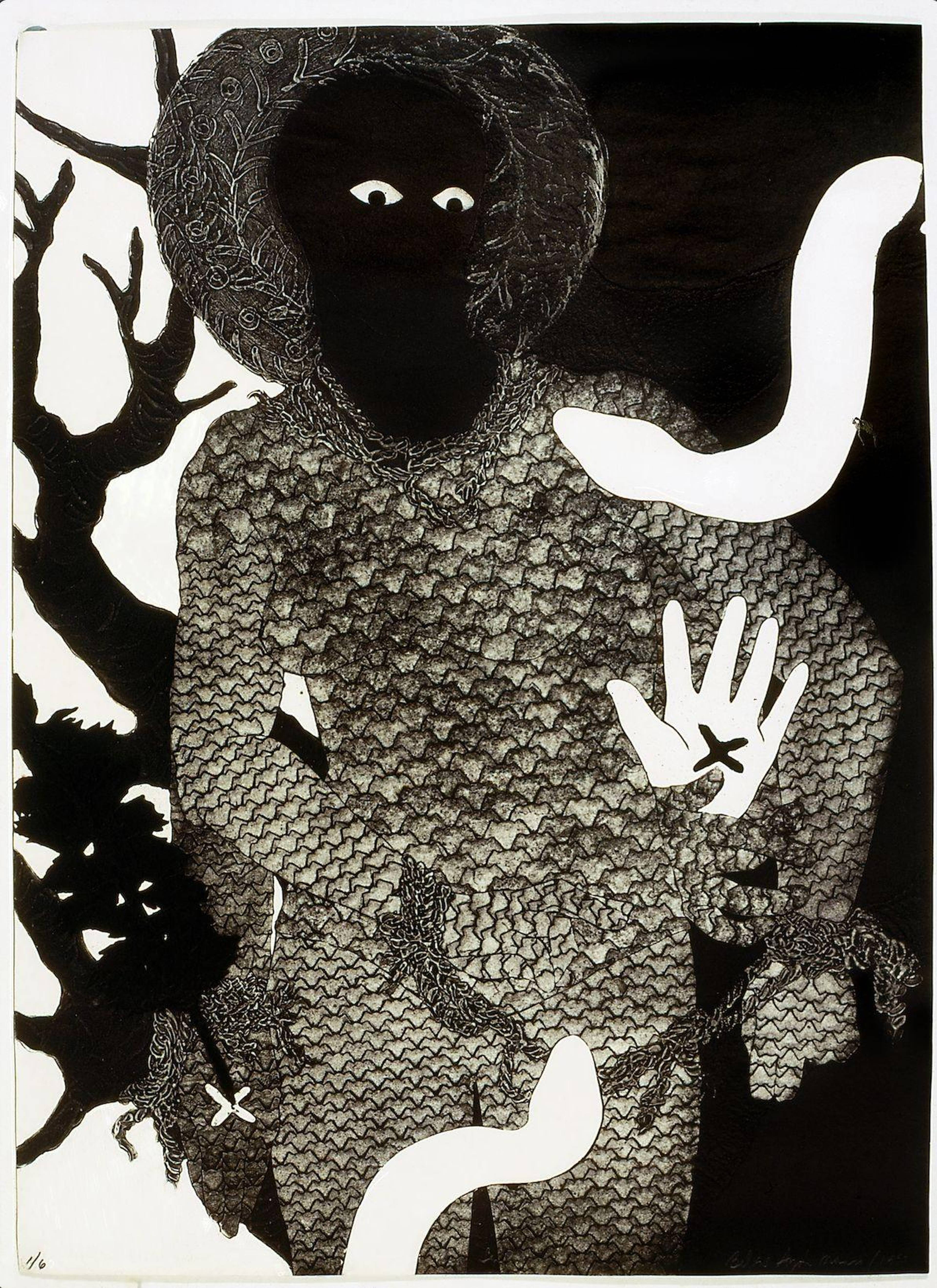

Belkis Ayón, La Sentencia, 1993. Belkis Ayón Estate

The show’s great set piece, which lifted me up and took me away, is a sequence of the top floor, coming right off the stairs, that bustles like a witch market with mystical figuration and divination. Jaider Esbell’s shimmering disco kanaimés , with skulls concealed behind their backs, open dramatically onto a room of monochrome collography by Belkis Ayón, a Cuban artist. Her prints illustrate stories about the Abakuá, an Afro-Cuban secret society consisting only of men, and Princess Sikán, whom they wished to kill and take her secret. Ayón shot herself dead on September 11th, 1999, aged 32, and nobody knows why.

Jungjin Lee, Buddha series, 2002

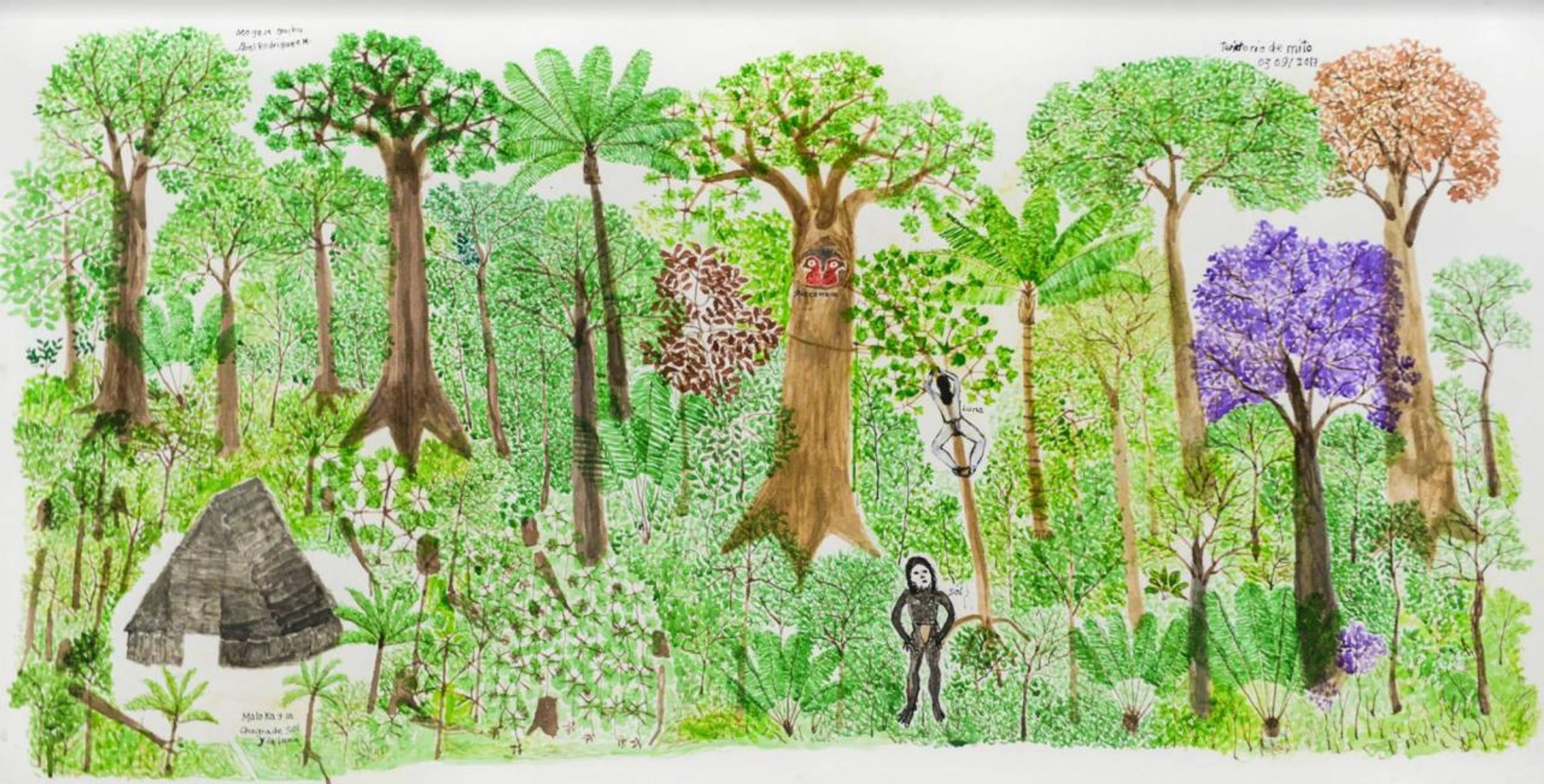

Around the corner are Jungjin Lee’s photographs of old Thai statues of Buddha in ruins, crumbling but eternal, blown up massive on traditional textured Korean hanji paper. Nearby are Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s painted collages of American animals and symbols; Abel Rodríguez’s drawings of the forest from memory, in which each leaf is painted and every plant labelled, and the animals that live around them drawn in too, making a portrait of the rainforest that could continue forever; and Daiara Tukano’s square of sacred birds, who protect her people from the falling sky and burning sun.

The rainforest is speaking to us. And what’s it saying? That it’s a sacred place. That it’s dying. That it’s dangerous.

Uýra, a Brazilian performance artist, shows photographs of themselves caked in makeup and wrapped in leaves, in rainforest drag, crawling through places where plants are reclaiming the city. They say they’re “a tree that walks.” The artist, like Bernini’s Daphne, is becoming a tree; and why not, for we live in an age of transformation. The rainforest is speaking to us. Well it’s speaking to Indigenous people, and they’re translating for us. And what’s it saying? That it’s a sacred place. That it’s dying. That it’s dangerous. That it’s full of entities and forces we don’t understand.

Abel Rodríguez, Territorio de Mito, 2017

This Bienal (much like the novel Leave Society , which I reviewed in July) appeals to ideas of old Indigenous cultures as utopian, and for the most part rejects the present. That rejection’s an idea that grows and grows in the present. The show feels made in an interzone in which the digital realm doesn’t exist, and phones, computers and the internet are almost completely absent from its halls. Other major exhibitions, like documenta and Venice in 2017, and the 10th Berlin Biennale in 2018, also took a similarly post-colonial and anti-technological approach, giving a prominent platform to overlooked communities and presenting a more balanced and equitable view of the world. This isn’t just a one-way process, however. By placing modern and contemporary artworks alongside forgotten histories, folklore and native visions, curators also may hope to restore some of art’s degraded aura, perhaps even some of the mana and spiritual meaning that has been lost; to borrow or steal some magic from the shamans. Like Pierre Verger, like Joseph Beuys, artists might once again aspire to become diviners themselves.

Uýra, Tudo de Novo (Retomada series), 2021

“Though it’s dark, still I sing” plays like a lament for what has been lost, and what shall not transpire, but as befits its title, it’s not without its bright notes. On my first afternoon there, resting at the top of the winding double-helix walkways, for some moments the whole building played like an orchestra, led by Yuko Mohri’s spinning loudspeakers and joined by so many other sound pieces and videos, sometimes dance performances too, calling out across the sunny atrium like birds in a canopy, and making the air hum and vibrate.

Down the opposite end of the hall hang some pieces by Israeli choreographer Noa Eshkol. In 1973, when one of the dancers from her quartet was conscripted in the Yom Kippur War, the rest vowed to stop dancing until he returned. To pass the time, Eshkol and her dancers began making colourful abstract patchworks from cast-off fabrics and clothing. They continued making these through the Eighties and Nineties, often giving them evocative romantic titles like Sunset by the Lake. Again it’s unclear whether they’re artworks or not. It doesn’t matter. They’re objects with a story.

At Casa do Pôvo (“House of the People”), a leftist community centre and Jewish history archive in Bom Retiro with a decidedly utopian feel, more documents pertaining to and videos of Eshkol with her dancers in the studio are displayed in the second-floor library. Up another flight of stairs, the empty top floor of the casa is hung with more of their patchwork rugs. It’s the most beautiful room in the Bienal. Above, up on the roof, is a shared community garden, and a scaffolding tower you can climb by ladder and see the wide concrete city rising up on all sides without end.

Noa Eshkol, "Corpo coletivo" at Casa do Pôvo. 34th Bienal de São Paulo. Edouard Fraipont