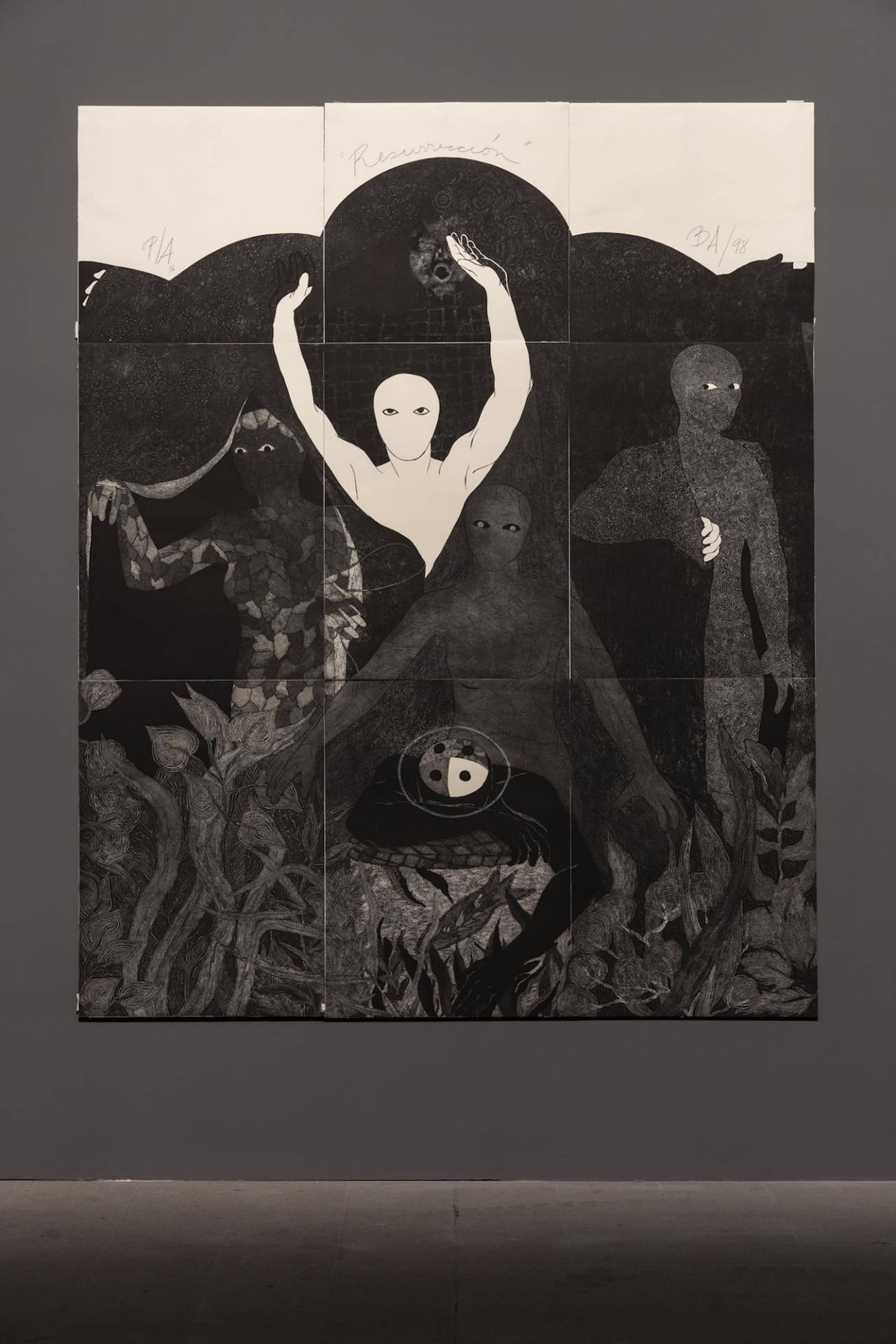

The first gallery of this year’s Venice Biennale exhibition features a monumental Simone Leigh sculpture of a black lady with braided hair turning into a building, surrounded by a series of eerie collographs by Belkis Ayón (1967–99). These prints illustrate mystical stories about the Abakuá, an Afro-Cuban secret society only men were allowed to join, and Princess Sikán, whom they wished to kill and rob of her secret. From the very start, the gender divide is made apparent.

Cecilia Alemani has curated a majority female exhibition, in which around nine-tenths of the artists are women or nonbinary, and a racially diverse one too, with more nations represented than ever before in Venice. The only straight white guy in the show, I was told, at least one of very few, is Diego Marcon. His opera of the disfigured tells a tale, quite appropriately, of a father, a patriarch, who has murdered his entire family, including himself. Daddy sings about killing his family, they sing about him killing them. Elsewhere, Raphaela Vogel sculpts a morbid carnivalesque procession of an oversized anatomical model of a diseased, malignant penis on wheels dragged through the old Arsenale shipyard by a ghostly white troupe of rotten giraffes. These are two of the highlights of the show.

There’s not much that’s surprising here. Simone Leigh’s giant bust was commissioned for New York’s High Line, where Alemani is also curator, and exhibited prominently on the spur crossing 10th Avenue, in Hudson Yards, from 2019 to 2021, and a copy was also installed at the entrance of the University of Pennsylvania in 2020. Leigh was awarded Venice’s Golden Lion for best contribution to the exhibition for it. She has the American Pavilion this year, and was also included in the Whitney Biennial in 2019.

Belkis Ayón, Resurrección, 1998, collography on paper, 9 sheets, 263 cm x 212 cm. Courtesy: Watch Hill Foundation; Von Christierson Family; La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Roberto Marossi

Belkis Ayón, likewise, was a star of the 10th Berlin Biennial in 2018 and the 34th Bienal de São Paulo last year. In São Paulo I wrote that the show’s great set piece, which bustled like a witch market with mystical figuration and divination, was how “Jaider Esbell’s shimmering disco kanaimés, with skulls concealed behind their backs, open dramatically onto a room of monochrome collography by Belkis Ayón.” She killed herself on September 11, 1999, for reasons that remain a mystery. Esbell, an indigenous Macuxi artist and activist, also killed himself last November, before the São Paulo Bienal – of which he was the star, with many dazzling paintings in the Bienal Pavilion, a show of indigenous art he curated next door, and two giant inflatable serpents on the lake in Ibirapuera Park, which could be seen from the planes in and out of the city – had closed.

The Venice Biennale is not supposed to shock or to upturn convention, but rather to provide an enjoyable, more light-hearted compendium of the trends of the day for an audience of art-lovers and cultural holidaymakers.

Esbell also appears here in the Arsenale, where his psychedelic paintings decorate a cocoa-fragrant hall filled with a maze of massive blocks of earth, raw cacao and spices by Delcy Morelos. He’s one of a number of indigenous artists in this Venice Biennale, and one of many artists making spirits, magical beings, folklore, and metamorphosis their subject matter; all of which are major trends in contemporary (post-Weirdening , post-Mayan Apocalypse) exhibition-making. Five years ago, the last time I went to Venice, in the midst of a documenta in which indigenous artists also played a central role, I saw, outside the “Pavilion of the Shamans”, Huni Kuin tribespeople leading conga lines through the opening-week crowds of dealers, curators and critics milling around the Giardini, like a scene from a Fellini film. Five years later and not much has changed. There’s not much that’s surprising here, nor is there supposed to be: the Venice Biennale is not supposed to shock or to upturn convention, but rather to provide an enjoyable, more light-hearted compendium of the trends of the day for an audience of art-lovers and cultural holidaymakers.

The Giardini half of the exhibition opens with a huge sculpture of an African elephant by Katharina Fritsch and nothing else. The elephant in the room. Another elephant in the room is that lately biennials are always about the same thing: identity. That’s not to say that the artworks themselves are necessarily linked with identity (though many in Venice are), but that today’s curators and institutions have grown more interested in the identities of the artists than the art that they make, and this is what shows are now organised around. It’s a trend Sean Tatol of the Manhattan Art Review tackles in his polemical review of the Whitney Biennial, where he says, “Meaning cannot be sutured onto a work by simple facts such as the artist’s biography or identity, because such things have no inherent tie to the quality of the work. The entire objective of art is to represent affective phenomena, and if it becomes possible to experience that representation through background details about the artist then art becomes effectively useless.”

Diego Marcon, The Parents' Room, 2021. digital video transferred from 35mm film, CGI animation, colour, sound, 6:23 min. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Roberto Marossi

This turn to identity has been a huge shift, and one that’s taken place recently, over the six years of this column, during which time the top-down understanding of what art is and should do has changed completely. I have an acquaintance that worked on Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s documenta 13, the documenta of Pierre Huyghe’s sculpture covered in bees in the woods, Tino Sehgal’s pitch-dark shed full of songs and Theaster Gates’s abandoned hotel, back in 2012. That exhibition, they say, was “peak art-world theory/wordcel. Overweening ambition to expand into all fields of knowledge and present art as an infinite research program. I found it infuriating, dilettantish, but maybe that’s because it cut too close to home.” By documenta 14, most of that research and theory had already been abandoned for a very different set of concerns; and alongside this, there was also a retreat into very conservative forms of painting, sculpture, ceramics, and textiles, to an extent that would seem absolutely baffling and psychedelic to anyone just seven or eight years ago. Sometimes I catch myself wandering around a museum, gallery or fair, having forgotten what year it is, and see the painting, or the pot, before me afresh and am startled and wonder, What the hell is going on?

Every major exhibition I’ve visited over the past five years has been about diversity, identity, resistance, the 20th century, colonialism, magic, craft, or some combination thereof: documenta 14 and Venice in 2017, Gabi Ngcobo’s Berlin Biennale and Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfeld’s New Museum Triennial in 2018, Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley’s Whitney Biennial and Zoe Butt, Omar Kholeif, and Claire Tancons’s Sharjah Biennial in 2019, Jacopo Crivelli Visconti’s Bienal de São Paulo, Margot Norton and Jamillah James’s New Museum Triennial, Ruba Katrib and Serubiri Moses’s Greater New York in 2021, David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards’s Whitney Biennial this year, and now this women’s Biennale.

Art should affirm the joy of being alive. Alemani wishes to enchant us, and that’s what I want too.

There’s always a focus on the deep richness of identity, the danger of rationality, the marvellous wonder of indigenous thought, the desire to make love to the forest and so forth. Cecilia Alemani’s achievement has been to gather together these by now somewhat uninspiring, worn-out threads and weave them into a coherent, uplifting, at times beautiful, at times revolting story. She wastes little time speaking about the pandemic, the uncertainty of our times, the acuteness of our anxieties, or any of the usual platitudes and excuses, encouraging us to think instead about the far more interesting question of how our understanding of what it is to be “human” has changed and might continue to change. Her concerns are posthuman. It’s great that this show’s not about “causes” or raising “awareness” or whatever, and to the extent that she attempts to teach us anything (hardly much), what she’s giving us is an alternative, more magical and untold history of 20th-century art and society.

Nearly half of those included in this Biennale are dead. As is the trend in contemporary art, Alemani has gone back into the past to find old and forgotten artists. But rather than just dropping in random figures from the past without explanation, she presents a coherent and thought-through framework from which her alternative histories can unfurl. There are five historical shows contained within her show: “Seduction of the Cyborg”, which traces a lineage of posthuman blends of the human and the artificial back to Weimar Hamburg Expressionist dance troupes; “Technologies of Enchantment”, which covers 1960s Programmed Art and kinetic abstraction; “Corps Orbite”, which remakes a historical showcase of female Visual and Concrete Poets; “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container”, a group show of vessels; and “The Witch’s Cradle”, a survey of female Surrealists like Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, Claude Cahun, and Leonora Carrington and the fantasy realms and characters they dreamt up. This Biennale also has a clearly stated theme: “The Milk of Dreams” takes its title and premise from a children’s book by Carrington (1917–2011), published after her death, and intends to show how everyday life can be transformed into something more fantastic, an enchanting place in the imagination; how another world is just a dream away.

Marianna Simnett, The Severed Tail, 2022, three-channel video installation. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Roberto Marossi

Art should affirm the joy of being alive. At least that’s one of the things it could do that I’d like. Alemani wishes to enchant us, and that’s what I want too. She proposes that our imaginations can set us free from the gloom and the pessimism of the present. Life feels as strange as fiction, why not retreat even further into dreams? Abandon your screens for the real world. Abandon the real world for dreams. Escape from the present right into the past. Return to childhood, to a children’s book written by an occultist. Leave that human body behind. Become something more! This exhibition rejects the internet and the phone, the media landscape, the canon, masculinity, earthly forms, scientific ways of thinking, in exchange for spellbinding takes on life, indigenous forms of knowledge, suppressed histories and cosmologies. Great faith in divine femininity. Desire to speak to the animals. Such ideas may be familiar to readers of this column. Does Cecilia Alemani want to … leave society?

An abandoning of reality, a turning inward to dreamworlds, might be a powerful force of emancipation.

“Humans”, Tao Lin suggested last year in his novel Leave Society, “seemed to be deep into a brief, fallible transition called history – a twenty-millennia release from matter into the imagination, a place that was to the universe as life was to a book: larger, realer, more complicated.” He too thinks that an abandoning of reality, a turning inward to dreamworlds, might be a powerful force of emancipation. “Humans everywhere”, he writes, “were nudged and shoved and pulled and lured away from matter, toward the increasingly friendlier dimension of the imagination – away from inflamed, deformed, poisoned bodies and the ad-covered, polluted outdoors, into beds, books, computers, fantasies, dreams, memories, art.” The mandalas he draws would have been great for this Biennale, but are instead on show at a kava and kratom bar in Williamsburg. It closes this weekend. Eight people threw up at the opening I heard. I’ve never drank kratom but a shiny new kratom bar has just opened up close by, across Avenue of the Americas, so I guess I’ll give it a go. It’s a heroin-substitute tea derived from a Southeast Asian tree and used in religious ceremonies there; a milk of dreams.

There’s a character in Leave Society that’s in the Biennale as well. In the book they’re called Rainbow. They join these two worlds. As I approached the last room of the Arsenale, the great finale, a tingling faint whirring noise made itself present. Some whiffs of manure. A doorway, a sign:

“Si segnala la presenza di lepidotteri.

We report the presence of butterflies.”

On the other side is Rainbow’s, or Precious Okoyomon’s, garden, where kudzu grows among raw-wool black female figures encrusted in soil and blood; the artist’s own. It’s a peaceful, bucolic setting. The butterflies, which make up a work of their own, The Sky Is Always Black Fort Mose, are hidden away, they’re sleeping. But around dusk, at the end of the day, I heard, when the lights are turned on, they all wake up and the secret garden blooms with thick clouds of black butterflies, and it’s enchanting, I’d imagine, though hardly anyone will see it but the sculptures and the butterflies.

Tishan Hsu, Watching 3, 2022, UV cured inkjet, silicone on wood, 182.9 x 121.9 x 10.2 cm. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Roberto Marossi

Precious’s artworks and poems are full of love and aimed towards transcendence. Tao also makes ambitious and visionary claims for literature and what it might do. “Maybe slowly”, he writes, “was the only way to reach the other side of matter – not crashing through with time machines or electromagnetic interferometry, but crafting a planet-sized art object, a context lasting and magical enough for greater magic to appear.” He suggests it’s in the imaginary realm that we can be free. Alemani suggests this too; and what she is able to do that’s different, is to synthesise the old myths of spirits and transformation with more recent transhumanist currents, and so draw another way forward. She opens a path forward when so many exhibitions only look back. Her histories lead in the end to new takes on the cyborg, from Marianna Simnett’s furry fairytale about a poor chimeric pig-girl pursued by sleazy S/M techno dogs, to Tishan Hsu’s (“I consider myself a cyborg. Google is my memory”) body-horror tables in which skin melts into screen and waxy faces come up for breath, unhappy with their lives in the pod, to Giulia Cenci’s 150 metre-long installation of human heads and horse’s backsides and legs cast in mineral resin and suspended in the sky above the walkway to the exit, ready to run across the heavens.

In Venice, as in most of the art world since 2017 at least, there is again a deliberate and considered rejection of the present and the way we live now. We’re invited into a world without phones or computer imagery; though not completely. Like a handful of survivors from a forgotten apocalypse, a few artists working with recent technology have made it through: LuYang’s virtual alter-ego Doku floats over a devastated metaverse questioning the nature of existence, giving a soliloquy on their willingness “to die over and over again” before slowly exploding part by part in outer space. They’re the only artist in the Biennale using CGI animation. Sondra Perry goes looking for the histories of her neighbours and family and data-moshes the resulting footage so that hands dissolve into bodies, into trees into lush pools of colour, and rolls her narration through a warm, fuzzy vocoder. Shuang Li’s soaring video-poem looks shot by selfie-stick and drone, and lit by a ring light, wrapped around its environment by a very wide lens, while a catgirl rolls around on the bed and speaks about pixels and how we’re all full of light; and these are all highlights of the show.

We have forgotten how to imagine a different world, that’s all.

In places “The Milk of Dreams” shows a side of the present and the future as frightening, but limitless, but potentially enchanting as the old world of myth. Today we really do live in a time of chimeras and metamorphoses. Chimeras are being put together right now in America and elsewhere. Silicon Valley savants are building psychic connections between us and the monkeys, Neuralinks, which are effectively shamanistic devices. There are robots that imitate hounds and software that imitates brains, and all kinds of cyborgs. Stories from mythology are finally coming true. Magical ideas are happening right now, even if most of that is happening outside of art, even if many of us have succumbed to doom and collectively fooled ourselves into believing that progress is no longer taking place or even possible. Not so here. Alemani’s exhibition paints a much brighter vision: we have forgotten how to imagine a different world, that’s all. We need only to remember how to imagine again; by returning to our childhood, perhaps, or stepping outside of society, or our bodies.

Venice generally represents an ending rather than a beginning. So this might be the close of a five year cycle; after five years of more of the same, what comes next? One hundred years of shamans? Decades more of celebrations of diversity? Hopefully art will now be set free to move onto other topics; to itself be transformed by the imagination, by dreams. And, if we must stay inside of ourselves, we can at least hope for a more visionary period of cyborg experimentation with the limits of identity and humanity. There are some great lines LuYang once said about transitioning into an artwork in the metaverse:

“In the virtual world, I was able to do things such as choosing my own gender-neutral body and creating an appearance that reflects my own sense of beauty, which are not possible in real life. I consider Doku as my digital reincarnation. He is me but someone else at the same time. Just like the Buddhist concept of ālāyavijñāna [storehouse consciousness], he represents a stream of consciousness which lingers in different worlds and different selves.” In this reading, art and technology are creative spaces where we can sculpt our identities and explore our many different selves, and prepare those selves for new worlds. A whole virtual cosmos of infinite possibility expands around us; one in which our identities are the form, and we are the material.