A year ago I went to the Guggenheim, for the show about the countryside, which is still up now, where the tomato plants in the greenhouse out front have grown wild and unruly, and stood by an upstairs window looking out over the Central Park reservoir, in which a large vortex of ducks had begun rotating backwards. That was taken as an ominous portent, and has proven so. This winter’s Northern Shoveler Vortex, so far as I’ve heard, is no longer so unusually large, and has resumed a hopeful clockwise rotation.

On Sunday evening I watched a lone shoveler paddling through the still waters below the North Pumphouse. A few dozen people with telescopes, binoculars, and cameras waited at the edge of the reservoir, and on the footbridge, in the ice and the gloom, in near silence, aside from the sound of a barking dog that could not be stopped. The drawn-out, rippling reflections of the lights of 5th Avenue’s luxury apartments looked cold and impressionist. Further down, to the South, the tall narrow towers were wrapped in curls of clouds. Our visitor was supposed to arrive around 6:35 PM, as on previous evenings, I’d read, but did not. The evening before she’d been hunting ducks on the water without luck or technique. I imagined her floating silently, slowly, low over the water towards us, and everyone sighing with delight in chorus. The minutes ticked by. My friend was supposed to arrive at 6:40 but he was late too. It was so cold.

At 7:00 there was a muffled shout and the Snowy Owl flapped up onto the roof of the Pumphouse from nowhere, just appeared, and sat there above us facing the crowd, and there was a genuine sense of wonder, of a magical being having arrived. A spectre. A young white witch come down from the Arctic to make a home here for a while. She’s the first famous owl to have arrived in the city since Rocky, the stowaway saw-whet who came in with the Rockefeller Christmas Tree some months back, and the first snowy owl seen in the park for 130 years, since 1890. Everyone gazed up at her, binoculars and words of excitement were shared around among strangers, and five minutes later she glided back down into the crystal woods like a ghost, and all were satisfied, and made their way back home.

The last time I joined a group of strangers waiting in the cold with expensive cameras with telephoto lenses, it wasn’t an owl that turned up, but Gigi Hadid and her baby, returning to their Bond Street apartment.

There are around 300,000 Snowy Owls, compared to 7.8 billion human beings. There are so many fewer wild animals than people left. Rare birds take on the aura of celebrities, or mythical beings, when they come to Manhattan. They’re photographed every day, and their movements and locations are regularly updated, often right down to the exact potted shrub on the street, the particular branch of the tree where they are, on Bird Twitter.

Leaving the reservoir I stopped on the footbridge, looking North toward the tennis courts, the frosted trees, the glittering snowdrifts, and saw my friend Sunil come skiing underneath me, under the bridge. I followed him on his cross-country yomp round the park. Through the woods, by the shore of the frozen lake, the meadows of decapitated snowmen, and gusts would come stir the trees and shake great snowfalls down over us, like we were ambling through a Calvin & Hobbes strip, which is how I always imagined America, growing up. When I was a child I felt like I was watching the world from the outside, looking in. Now I feel like I’m watching from the inside of a soft, glowing cocoon of screens and shut doors, and having the same gentle day over and over, like there is no world. So it felt great, and life-affirming, to break free for an evening.

At the hotdog stand on the corner, we had hot dogs for $2.50 each, far less than I recalled, and steaming hot cocoa for $1.25. Business was down, said the vendor, 60% from how it used to be. The cocoa tasted cheap and powdery and so, so good. At 42nd Street, transferring from the A to the F, I could hear a hymn I liked, and followed it. On the upper level a man was playing his angels’ song one-handed on a trumpet, over his backing track on a phone and speaker, and blessing everyone for a dollar. There was a peaceful, magical feeling on the subway that evening.

I saw the Duck three years ago, down in the icy pond at the bottom of the park, by Trump Tower and Vuitton. He was a Mandarin drake and looked like a rare Qing Dynasty porcelain teapot. He bobbed around all winter and entertained great crowds, until one day he disappeared, was never seen again.

Last week I was jogging along Hudson River Park and ran up on a peregrine falcon, closer than I ever expected to come to one, and saw the hawk rise up into the air, and slowly drift over the boardwalk, before alighting high up on the monolithic Holland Tunnel Ventilation Shaft in the middle of the river; and this hawk, this duck, this owl, were all heartbreakingly beautiful.

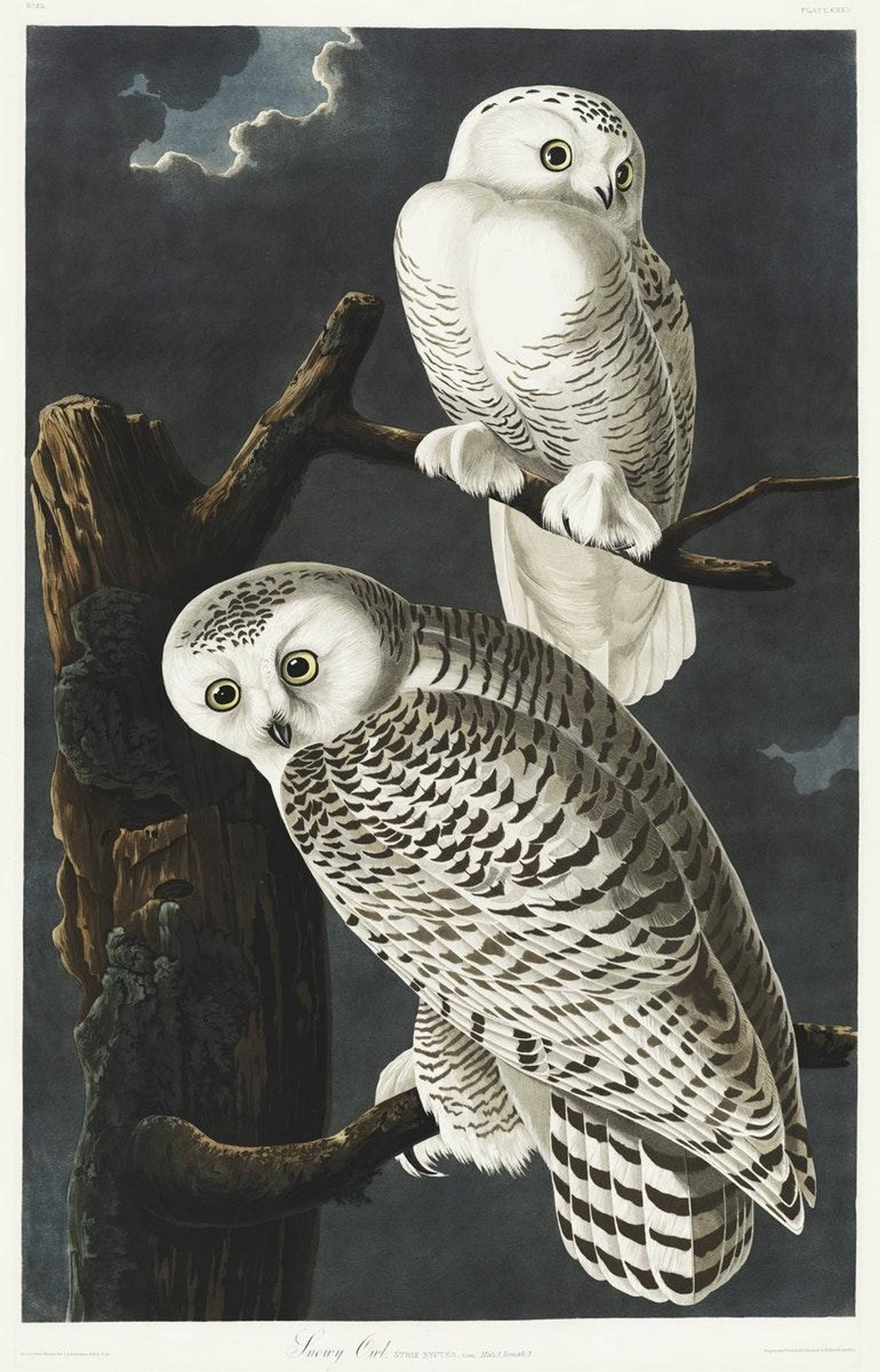

John James Audubon, Snowy Owl from Birds of America, 1827, etched by William Home Lizars

In the past I’ve written of how scientists are engineering chimeras, and how Juan Carlos Izpisúa Belmonte, of California’s Salk Institute, is collaging human stem cells into monkey embryos at an undisclosed location in China. Last week on Clubhouse, Elon Musk described how his company Neuralink has implanted a brain-machine interface in a monkey, allowing it to play video games with its mind. “He’s a happy monkey,” said Musk. “We have the nicest monkey facilities in the world.” They’re testing this on monkeys before humans, with the goal of eventually using the technology to help ameliorate the damage done by brain and spinal injuries. Presumably it will also be used, by Neuralink or others, to allow us to play League of Legends , scroll OnlyFans, and trade Robinhood with our minds. To pull us deeper into the network. But, my friend Yuri Pattison says, “the real promise is human/ animal telepathy.”

A monkey with a Neuralink playing Death Stranding sounds like a Pierre Huyghe project; like those piebald chimera peacocks on the outskirts of Münster, in the abandoned ice rink with the sharded roof that opens and closes according to the division of cancer cells. At the same time however, it evokes the beginning of art, and cave paintings, in which human beings are rarely depicted, and when they are, have often transformed partway into animals, as is the case with the three great mysterious characters from prehistoric figurative painting: the Bird Man of Lascaux, the Bison-man of Chauvet, and the Sorcerer of Les Trois Frères.

Some years ago in Bergen, Norway, in the café of the Kunsthall there, I met a postgraduate researcher who was studying cave paintings. She told me that the most surprising quality of the reindeer, elks, and wild horses running along the walls of the caves, was how accurately their footfall patterns were painted. They would not be captured so accurately again until 1878, when Eadweard Muybridge made his photographs of a galloping horse at the racetrack in Palo Alto, in the heart of what is now Silicon Valley. The artists in those caves understood the movements of the animals they worshipped better than their eyes could see, she told me; and this was only possible, if they had become the animals themselves, had possessed them, she said.

When I was a child I felt like I was watching the world from the outside, looking in. Now I feel like I’m watching from the inside of a soft, glowing cocoon of screens and shut doors, and having the same gentle day over and over, like there is no world.

More news from this year: two shamans took part in the storming of the United States Capitol, and a spinach was taught to email; which is to say, the roots of a spinach plant were engineered to contain chemical nanosensors capable of detecting the presence of nitroaromatics, which are often found in explosives, in the soil. “We have overcome,” said MIT’s Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering Michael Strano, who led the project, “the plant/ human communication barrier.” Another way of interpreting this is that our leafy greens aren’t quite communicating with us, but we’re able to use nanotechnology to transmogrify them into living notifications.

New sorts of connections with nature are becoming possible; not through shamanic possession, but technology. These telepathic monkeys, this spinach with a Substack, are new kinds of emissaries between the natural and human worlds. When a snowy owl turns up after dusk, and a crowd are there waiting for her by the reservoir’s edge, she might also be considered an emissary.

We’re living in a futuristic world now, but it’s a strange future, not at all what most of us were expecting. We don’t have flying cars. We have electric cars, and the world’s richest man is an electric carmaker who’s placing telepathic devices in monkeys’ minds; he is, in the fantasy parlance, a warg. It’s not what we expected, but is in many ways more interesting, more mystical and pagan. I’d much rather have psychic connections with animals, than hoverboards or flying cars. The future should not be a place we can easily imagine. It shouldn’t look like it did in the movies. It’s more exciting to have the weirdest future possible, in which one might become something other or more than a person, and try to see the other worlds as our ancestors wanted to, and might indeed have done, and then to go further.