The Whitney Biennial just opened in New York. In his review, Jerry Saltz suggests that curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards have left out “what may be the most impactful video made in the 21st century. This is the ten-minute-nine-second continuous sequence made by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier of Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd.” Given the controversy over the painting of Emmett Till five years ago, to include that video would have been a crazy curatorial gambit. Though as Saltz points out, there’s clear precedent: George Holliday’s video of the beating of Rodney King by LAPD officers in 1991 was included in the 1993 Biennial, an edition which the curators echo and evoke, having included five of the same artists in theirs. The most impactful videos of the post-9/11 world, it’s true, have mostly been made by ordinary people on their phones. Such videos have changed the world. The furious, sometimes violent protests of early summer 2020 derived much of their power from the way they were streamed live from the scene, by those at the heart of the action, driving it forwards. Events on the street happened everywhere at once.

Although there are no videos of police killings in the Biennial, there is a cinematic restaging of police violence: Alfredo Jaar’s 06.01.2020 18.30 installation (2022) combines (SPOILER ALERT) black-and-white, first-person footage of a protest in Washington, D.C. on 1 June – where officers fired tear gas into the crowd while National Guard helicopters hovered just fifty feet above – with powerful ceiling-mounted fans pointed down at the audience like spotlights. When the helicopters loom closer, the fans blast you with cold air. The room’s a synthesis of every recent Whitney Biennial scandal: racism, tear gas, the virtual-reality staging of violence. Now you, the audience, can experience how it feels to be attacked by police, buzzed by army helicopters, and bombed with tear gas; in a highly aestheticized, theatrical fashion. Protest is remade as theme-park spectacle.

Jaar’s simulation uses 4D-cinematic wind and surround-sound effects to make the events he depicts feel real. They feel more real than the war happening now, which for most in the US is experienced only through a phone, on the little cracked screen in two dimensions. It’s a deeply surreal experience I never expected to have: a major land war in Europe seen darkly, distantly through the glass of content. Even those fleeing the war, and those caught in it, or fighting, it seems, are experiencing much of it through their phones.

Broadway, Manhattan, 2nd of April 2022

I saw this poster, this palimpsest on Broadway. Pink and red letters stencilled over found pages of the New York Times: “The Russo-Ukrainian War Did Not Take Place”. They know there’s a war going on, but this is a reference to “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place” (“La Guerre du Golfe n’a pas eu lieu”), a collection of three essays published by Jean Baudrillard in Libération and the Guardian between January and March of 1991, as the United States invaded Iraq for the first time (it was also on 3 March, 1991, that the LAPD pulled Rodney King out of his car and beat him on the ground). Baudrillard believed the first Gulf War was not really a war but only an atrocity disguised as a war, because the US fought with overwhelming airpower and took very few casualties; and also because those outside of Iraq were only able to see the war through propaganda imagery beamed into their homes as TV news. It was all closely stage-managed and misrepresented through simulacra, replacements of reality with its image. We did not experience the war, but only a mediated version of it. Today’s conflict is more mediated and more unreal still. The simulacra of war grow weirder and weirder. War feels like a video game when you’re watching, as I am, artillery strikes filmed by drones in the sky then posted with an upbeat hypnagogic pop soundtrack; a vaporwave song for a vaporwave war.

How propaganda functions has also changed dramatically. Propaganda no longer comes from above. It comes from everywhere at the same time; it’s unclear where it comes from. War can no longer be directed like a TV show as its images, narratives and counternarratives are shared across thousands of different channels and platforms. Those fighting are often documenting themselves as they do, resulting in content warfare at a scale that hasn’t happened before: and videos such as this, from the Bratstvo Battalion (the “Brotherhood” Battalion) founded by Ukrainian writer and poet Dmytro Korchynsky; a right-wing militia and TikTok comms unit with a Rudnick -wave logo, a 4k hype house battalion fighting the orthodox war in HD.

One of those “The Russo-Ukrainian War … ” posters on Broadway is printed on a full-page advert in the Times for Palantir, the software company founded by Peter Thiel in 2003. The copy reads, below the stencilled slogan:

“Our software helps the military run missions from space.

It can power your global supply chain.”

Among many controversies, Palantir took up Project Maven, to design an AI to direct unmanned drone missions, after Google dropped out in 2019. Project Maven is raising autonomous weapons that choose who to kill and what to destroy. Perhaps, like a demon in the sky, fighting in the storm clouds, it will someday hold your own life in its virtual hands. So, this is a very Baudrillardian montage: an ad for the future of drone warfare under a message about a war involving a significant amount of drone warfare, a war that’s partly conjured by footage from said drones, that’s brought us folk-music videos celebrating Turkish Bayraktar drones.

We don’t see the war so it’s not taking place. What’s most surprising about these posters concerning the spectacle on Broadway is that they’re pasted up on streets that don’t feature any other anti-war graffiti, agitprop graphics, or anything like that. There aren’t other slogans or laments sprayed on these walls and empty storefronts. Only Palace X Calvin Klein ads. If you’re in Berlin, or somewhere in Europe, and your city is busy with refugees, and the frontlines are hours away, war must feel very close, but here in the centre of the world it may as well not be happening. It’s only in your phone, and even then, only really if you’re looking. It’s rarely brought up. I haven’t heard any marches pass under my windows, although I heard so many these past couple years. There are no protests here. I think we maybe don’t care that much because it doesn’t fit into a culture war framework. We’re all on the same side, more or less. There’s not much to argue about, so it’s not much spoken of.

Jonas Mekas, Requiem, 2019

I walked past the Russian embassy on my way to the Jewish Museum. Nobody was protesting there at the embassy. At the museum there’s a show by Jonas Mekas, who left Lithuania in World War II and made it, eventually, to the United States. It’s the best show I’ve seen in ages. Eleven deconstructed Mekas films made between 1962 and 2019 play one after the other in sequence. Every scene from a film plays simultaneously over twelve screens, their different passages of the soundtrack mixing in the air between them, and sitting there feels like seeing your life, many lives, flashing by you on all sides. It’s an overwhelming and disorientating experience; like an expanded TikTok, someone told me. The last film of the program, Mekas’s unfinished Requiem from 2019, which he was working on until 10:00 PM the night before he passed, cuts scenes of beatings and torture from the papers together with his own shaky footage of flowers, cities and beauty, set to Verdi’s “Requiem” from 1874. It surrounds and hypnotizes you with images of life and death.

At the Whitney’s opening party I saw a friend from Russia. We stopped for a glass of wine on the third floor, which was devoted to an archive of Kandis Williams’s Cassandra Press. He told me the war was consuming him, was taking up all his attention. They don’t show much on the news, he said. I agreed they don’t show anything on the news. But how would we know, we don’t watch the news.

We’re so used to judging misinformation in the context of a culture war, but not at all used to making such judgments in the context of a war war.

Today we can see so much that in the past we would never have seen. Horrors that would never be reported. My friend experiences the war through Telegram. He showed me what he looked at, his feed that he’d curated for himself; completely impenetrable to me, as it was all in Russian. He told me he’d seen so many war crimes, seen Russian prisoners of war shot in the face on his phone. He’d seen Ukrainian troops hiding out in apartment buildings and residents were shouting at them to leave, in Russian, begging them get out of this building, we don’t want this building to be bombed, he told me. I don’t know what is happening and what is not happening; but that is what he saw.

I don’t know what I’m seeing either. We’re so used to judging misinformation in the context of a culture war, but not at all used to making such judgments in the context of a war war. And we’re presented not only with simulacra but also with total illusions: the Ghost of Kyiv, the fighter ace, who’s “coming for your soul”. The deepfake bad actors who don’t exist, who are drawn, like one of Pierre Huyghe’s mental images, by AI. So much of our information comes from sources that cannot be verified. In the early days of the war it felt like we were experiencing a breakdown of social media communications on a colossal scale; a breakdown of reality. Today we can see so much that in the past we would never have seen, that may not even be there. It’s so hard to tell what has been misrepresented, or tampered with, or pulled from thin air, and where the cuts and the joins are. The fog of war now floats on the information level, around the world.

For the past decade we’ve been warned many times about Russia’s formidable information warfare capabilities, their dangerous troll brigades, which threaten our democracy, the fabric of our reality, our free will even; and yet Russia has lost the information war with Ukraine (and by proxy the West) by a large margin, from military intelligence and reconnaissance down to social-media narratives and memes. We might well wonder, where are the crack cyber warriors we were warned of, and what of the false consciousness they were supposed to have forged inside of us? Where are their political-technologist games and japes now, their deconstructions of reality inspired by avant-garde theatre and the transgressive performance art of Moscow in the Nineties? Was it all a lie? Were we responsible for our mistakes and failures all along? It seems we’ve overestimated the mind-control capabilities of Russia’s troll army, much as we overestimated the strength of its armed forces.

Intelligence dogs meme. Source: @YN_nope, Twitter, 12nd of April 2022

It would have been mad to include a film of a man dying in the Whitney Biennial. That said, I go on my phone and watch people die most days. I’ve seen the rockets strike the tanks and the burnt-out corpses of soldiers on the frozen ground. Civilians slaughtered in the streets of Bucha with their hands tied behind their backs. I’ve seen the war in my phone, the grim morbid spectacle. In March I texted a close friend, “Would you like to see a very brutal video from Ukraine?”

“Yes,” they replied.

It’s a clip from Hostomel, a suburb of Kyiv. It comes with a warning and is obscured. (You don’t want to watch this.) We’re a bloodthirsty society. I’m bloodthirsty myself; and drawn to the horror, I can’t turn away. I work all day and at night, before bed, lie down on the sofa and unwind watching videos of ambushes on my phone. Strangers dying in the palm of my hand, for nothing.

One night on Twitter I saw a soldier shot while streaming. He seemed happy, walking along filming himself on his phone, and then he crumpled slowly to the ground with a surprised expression, somewhere between agony and mirth. And then I don’t know what became of him. I’ve read that posts on the /VolunteersForUkraine subreddit have led to the deaths of hundreds of foreign combatants. They can’t stop posting and giving away their location. They’re admonished, “This is a war. This is not a vacation. Stop. Taking. Fucking. Selfies. And stop sharing them! Stop upvoting them! You are literally getting people killed! This is not a joke.” Posting has consequences, and brings real danger. But the desire is so powerful. We have such a desire to post even when we know we shouldn’t, when we know it’s a bad idea or it’s dumb, even when it kills us.

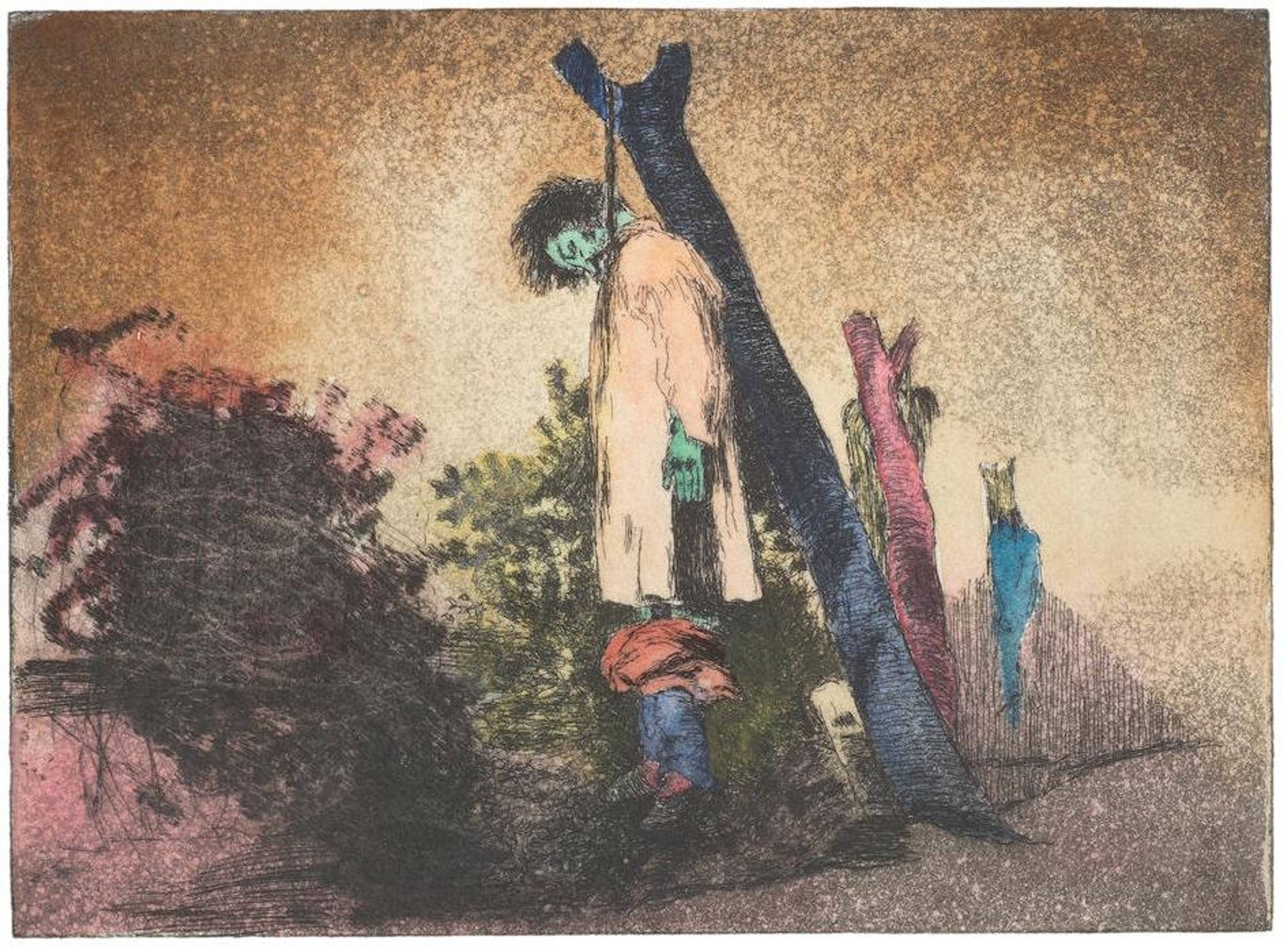

Where is our beautiful content? There’s a picture of the sky; cold curling baroque vapours drawn by the air defence system in the empty skies over Kyiv. There’s a recording of the national anthem broadcast over short-wave radio frequencies to jam enemy communications, to haunt the crackling airwaves. It sounds like Brian Eno in the Eighties. It sounds like different parts of Verdi’s “Requiem” resonating harmoniously over a Jonas Mekas exhibition. Moments like this feel more powerful than art, but are also a sort of performance in themselves. There are moments of beauty in the midst of the horror, the cruelty and apathy. Today’s great war poetry, today’s “Christ and the Soldier”, or “Dolce et Decorum Est”, will likely be content like this; chilling haunted moments roughly recorded, which may or may not be real.