On 20 March 2020, I thought in Washington Square Park the white and pink blossoms were so beautiful I could burst into flames. On 7 April it was springtime, there were house sparrows everywhere. They sang outside my window every morning and afternoon, a soft rolling warbling on the fire escape, and I thought, when I think back on this time, I will forever associate these days with the sparrows.

The sparrows are singing outside the window again. It has been two years since the pandemic began and now it’s in the process of being forgotten. Now we’re at war. In three years the great existential threat has shifted three times: climate change, pandemic, the threat of nuclear war again.

New York seems quite oblivious or indifferent to the war in Ukraine. It’s rarely brought up. I don’t see any flags. There aren’t many posters. Few slogans are sprayed on the walls. No marches have come by my windows. Nobody’s marching by chanting, “Wake up! Wake up!” Nobody’s banging pots and pans out their windows. There is nothing in the air. Outside it feels the same. Three girls are skating up and down the street filming content around a backpack printed with the word “brunch”. At Union Square Greenmarket a photographer snaps action shots of a disabled sausage dog bounding across the paving stones on two little legs and two wheels.

Last Wednesday, 2 March 2022, I was supposed to give a video lecture for the House of Europe in Kyiv. That talk could not happen. However, I was able to speak to two writers and curators from Ukraine who might have been in attendance – Kateryna Tykhonenko and Valeria Schiller – about their experience of the past two weeks since Russia invaded on 24 February. Kateryna is in Uzhhorod, and Valeria has just made it from Kyiv to Berlin. Eternal thanks to House of Europe’s Lina Romanukha for her help setting this up.

Kateryna Tykhonenko, 25, is a critic and curator from Uzhhorod, in Western Ukraine on the border with Slovakia. She returned there in December after leaving her job in Kyiv’s Mystetskyi Arsenal arts complex to go freelance. She’s also a co-founder of the independent art publication VONO paper. These are four entries from her diary.

24 February 2022

I couldn’t sleep last night, even though I’ve been in Uzhhorod for two and a half months now. It’s as if there is no war here, and I feel safe. But damn, how can I keep calm when my best friend from Kyiv messages me that she was woken up by explosions? I can’t control myself.

27 February 2022

I decided to volunteer here in Uzhhorod. Currently, I’m helping a local NGO to supply the Transcarpathian army and when I don’t have enough physical strength for it, I’m moderating a chat on Telegram where I inform refugees about possible host options, shelters and logistics. And I still feel like I’m not doing enough.

Before the Soviet Union invaded Transcarpathia in 1944, Uzhhorod was a peaceful Czech city. Its multicultural identity is still present, but these days it is more evident to me than ever before: people from every part of the country are walking on the streets of my hometown, most of them with children, they speak Ukrainian and Russian, and I can recognise the distinctive pronunciation of each region.

Some of them decided to stay and continue volunteering: men from the age of 18 to 30 who are unable to escape with their family because of conscription. Others are making a stop here to cross the border with Slovakia, Hungary or Romania.

3 March 2022

On the eighth day of the war, I don’t understand what I’m feeling now. It seems all my emotions have left me.

I have to act somehow, but it seems I have energy only for scrolling the news, watching videos, and lying in bed. I have to thank our national army and all the volunteers who keep Western Ukraine safe. They work while I sleep, and in the morning I have the feeling that I missed the news.

6 March 2022

It’s almost impossible to think about myself. I think about the people of Ukraine who are struggling, whose homes are destroyed. Where will they go to settle down when the war is over?

White Cube Poster by VONO paper

Valeria Schiller, 28, teaches art history at Kyiv Academy of Media Arts. She’s editor-in-chief of Ukrainian contemporary art site Artslooker , and has previously worked as a curator at PinchukArtCentre. We spoke on Monday, 7 March, the day she arrived in Berlin.

This is the second time I ran from Russia. Because I’m from Sevastopol in Crimea. So I had to do the same now as in 2014. I sensed the same again, that the war was coming before it came. It wasn’t clear then, but all of us were living in anxiety. And the tension of this anxiety was increasing constantly.

Some people, when I was talking to them before the war, were pretty careless and said that nothing will happen because some media was telling them nothing will happen. So all the American media was saying, yes, the war is coming, the war will start, I don’t know, within forty-eight hours. But if you read some European media, or even Ukrainian, and of course Russian news, no war. Zelenskyy gave a speech in January, and he said, “Stop thinking about the war. Everything’s fine. We’re protected.” The main idea of the speech was to calm everyone down. And of course, nobody wants to think, what should we do and how should we prepare?

Nobody thought one European country would occupy the territory of another back in 2014. Everyone was just so shocked. The same happened with coronavirus, because nobody was expecting something like that would happen. But no, this world is crazy, everything can happen.

*

I felt that this was going to happen again. I was fully packed before. I didn’t even have to pack. I called my dad the evening before because, I don’t know how to explain this, I really felt it. And I called him and said that I think this has started. And I asked, “Maybe we should leave now?” He said, “Nothing has started yet.” But he went to the petrol station so he had a full gas tank. This was a super smart move because when we did leave, every petrol station had huge queues of cars that morning already at 6:00 a.m. because a lot of people were leaving. My dad brought me and my mum to the Polish border and then came back.

The war started on the twenty-fourth; I mean it started again, on 24 February. So, all of us in Kyiv woke up at 5:00 a.m. because of the sounds of explosions, and the same happened to me. I was already packed and my dad called me and said that we should leave immediately. My mum wasn’t packed, so she barely has any stuff with her. But we left, I think, an hour or two after the war started again.

It was a long trip because all the roads were full with cars. I saw some haze from explosions that day. And when we were standing on the border I also saw some, I don’t know how to explain this, some things flying in the sky. I don’t know what that was. Some army equipment, drones. I think I heard some explosions. But also, I hadn’t slept for three days and two nights, and I started to see some hallucinations, so I’m not sure. It was my third night without sleeping and I felt like dreams were invading my reality. And I was starting to see dreams in reality.

*

There was a serious humanitarian collapse on the border with a huge amount of people. It was super crowded, and at one moment when twilight was starting to come, I recalled this story about Travis Scott’s concert (Astroworld in Houston, Texas, at which ten concertgoers died of compression asphyxia last November). I was standing in this crowd thinking about this concert and that was bringing me more and more panic. And I was sure that I was going to die there, because it was absolutely, absolutely crazy. I can’t explain it to you. It was a mass of people falling on one another and fighting inside of the crowd. Inside of the crowd, you cannot move forward or back. You’re trapped inside. This is a strange feeling when you cannot do anything. You just have to wait, or try to go forward.

At a certain moment one woman gave me her child to hold, because she was crying and panicking and she didn’t know what to do. And some people were leaving their bags and suitcases in the crowd because you either leave your suitcase and just try to survive, or you’re there another several hours. That was a mess, where we had to stay outside in the cold for several days. That’s what was happening.

Crossing the border into Poland was a super interesting experience. I wasn’t expecting that because everything I’d read before about refugees, was that everybody hates them and you have to hide and survive somehow. But after standing for three days and two nights on this border with these hallucinations, without food and toilets, and feeling so cold, me and my mum, we crossed the border and it was just like heaven.

I was afraid when I crossed the border and I asked the lady there who was stamping our passports, “Should I apply for asylum right now?” There are rules that you have to apply on the border or within several days. So I asked her if I should apply, and she said, “No, you just go.

“But I can stay only ninety days.”

“No, everything’s changed because of the war. You can stay however long you need.”

We went further and there was a huge field kitchen with soup. And we just cried hysterically when we saw the soup because we hadn’t eaten for two days. It was so nice. Several people from the Polish side came over, who were working on the border, and asked how we were. It felt like we’d just run a marathon. They were cheering for us.

I felt that a lot of Poles were afraid the war would expand into Poland too. I saw, I’m not sure if it was from NATO, but I think I saw a NATO helicopter flying near the border checking how everything’s going.

Shrine of the Virgin Mary in Volytsya, Ukraine, a village close to the Ukrainian-Polish border crossing point Shehyny-Medyka. Photo: Valeria Schiller

We took a bus for refugees and when we got off there were so many people, a crowd of people with signs like, “I can give you a lift for two people to Berlin, or to Munich, or to Prague.” Polish people who really wanted to help. Some were inviting us to stay at their homes.

One of my friends, Marko Markovic, an artist from Vienna, where I was on a residency three years ago, organised a whole escape-evacuation procedure for me and my mum. So there were friends of his friend waiting for us on the border, and they took us to Warsaw and we spent a week staying at the flat of one of them – at Julia’s – and they were super, super nice, preparing food for us or giving us clothes – things like that. That was just … I didn’t expect that much care, honestly.

When you walk around Warsaw, there are Ukrainian flags everywhere, and it’s free to use buses and trams for Ukrainians. It’s free to use the trains between Poland and Germany. You can enter all the exhibitions for free. I went to an exhibition of spiders, it was free. I mean, everything. People were walking on the streets with yellow and blue flags, or clothing. And some guy in the city centre of Warsaw made a voodoo doll of Putin and everyone, the whole crowd, was taking the small arrows, the pins, and sticking him with those. It felt like Ukraine because you take a bus and everything you see while riding it is yellow and blue.

I cried every single time I saw something moving and it happened, I don’t know, fifteen, twenty times a day. I didn’t expect that at all. I was crying the whole week. Not only because I felt bad for my friends and country, but also because it was so moving.

We had a tarot session. And the Polish friends we’re staying with were asking – just as a joke, but they were asking us what will happen to Poland. This is something that disturbs them and I feel that.

*

My Ukrainian landlady wrote to me a couple of days ago saying she cannot leave Kyiv because some of her relatives are ill right now. She was telling me that they don’t have any bread and they cannot find any. And my friends also told me today they’re somewhere around Kyiv and cannot find any food in stores. That’s what they told me. I’m not there. I can’t check, but I trust my friends. So this is a catastrophic situation.

Some friends of mine thought nothing would happen to Kyiv, because Kyiv is a beautiful place, who would bomb or shell Kyiv? They weren’t fast enough in leaving. And they’re still there, and now they can’t leave.

Two more of my friends were able to leave Kyiv on the evacuation trains yesterday. But it’s becoming worse; either you’re not hesitating and just leaving and you’re surviving, or you’re thinking and hesitating, and there’s a possibility you may not leave. I was talking to my friends, and I was thinking about how can I help them to relocate and find some people who can help them out. And my friends all told me, “Well, I’m not sure what’s more dangerous, sitting in the basement or trying to leave.” Because sometimes they – Russians – shell people who are just civilians and trying to leave, that’s what is said on the news. And that’s also what my friends are telling me.

Refugees meeting point in Przemyśl, Poland. Photo: Valeria Schiller

I have another funny story. (Not funny, but okay, I posted on Instagram this story about having survivor’s guilt.) And my friend, a curator from PinchukArtCentre, wrote me, “Oh Lera, I also feel that I can relate.”

And I asked her, “And where are you?”

And she said, “I’m in Kyiv region, close to Kyiv.”

She’s feeling this survivor’s guilt, but she’s close to the war, maybe even very close to the epicentre. That’s so crazy. How does that work? I don’t know.

Every day I’m trying to understand what can I do, what can I do to help, and I cannot find the right decision. It paralyses me from doing anything. Also, I’m having panic attacks and sometimes crying. Sometimes I’m trying not to read the news. Sometimes I understand that it’s impossible.

Sometimes I feel I want to speak up, I want to write an essay or something. I feel like, “Okay, good, I have an opportunity to think. I have an opportunity to sleep.” And I’m super privileged in that right now. Even though I feel bad, and I have panic attacks and I’m crying, I’m still physically safe and privileged. And then I think about my friends Tatiana, Milena, and Kateryna, who are in the middle of this war, and I think it would be maybe much more honest to give a voice to them, not to me. But I also understand that maybe they’re super concentrated and focused on survival.

*

I just arrived in Berlin so I’m not sure how is it here. I have seen some Ukrainian flags, but I think in Berlin people are more calm; still supportive, but in Warsaw it’s madness.

We were in Warsaw for a week and then I started to think of what to do next. All of my approaches don’t work anyway right now, they don’t exist anymore. They all are closed. I edit a website named Artslooker about contemporary art, and the idea is to share news about Ukrainian art internationally. I was editing, writing and trying to find funding. But the night before the war started again, the website stopped working and now I cannot even write to my IT manager because he’s probably fighting, because they’re posting that they’re actively involved in the war and volunteering. So it’s disappeared.

I don’t have a job. My dad doesn’t have a job. My mum doesn’t have a job. We don’t have a flat. I started to feel, what should we do next? We couldn’t live for long with this angel volunteer who helped us from the border, because we were living in one room all together. So we couldn’t do it for a long time.

*

There’s a wonderful artist, Andy Kassier, whom I interviewed six months ago. He’s not currently in Berlin and won’t be here for a month. When we were already in Warsaw he wrote, “Maybe if you need a place, you can come to Berlin?” And we had free tickets to Berlin, and I couldn’t find anything in Warsaw because there were too many Ukrainians already there. So the plan yesterday was to get here and then think about what to do next.

I don’t have a final destination. I don’t know what will be happening in three weeks. I don’t know. I will think about it. It’s too many things to manage and think about. I’m just trying to find anything. I’m trying now to apply somewhere and maybe find a job fast. I don’t know. I don’t know. I’m super lost. I don’t know what to do and I’m anxious. I think I will figure out something later. I don’t know.

Some friends of mine are also in Berlin already, which is nice because when you see a person during the war, a person whom you knew already, that helps. I mean, really, I’m afraid. How to say? It’s hard to accept. It felt like reality at a certain point divided and I chose the wrong path in this reality. It feels like that to me. Or it feels like some kind of nightmare and I’m just waiting. So, I will wake up and everything will be fine. Or is this another dimension, and I cannot find a path to join the normal dimension? It feels like that. I don’t know how to explain it, but also after not sleeping for a long time, it’s hard.

My main idea right now is just to calm down, and then calmly decide what to do next. Yes. Today we are much better than we were a week ago. A week ago, it was a mess.

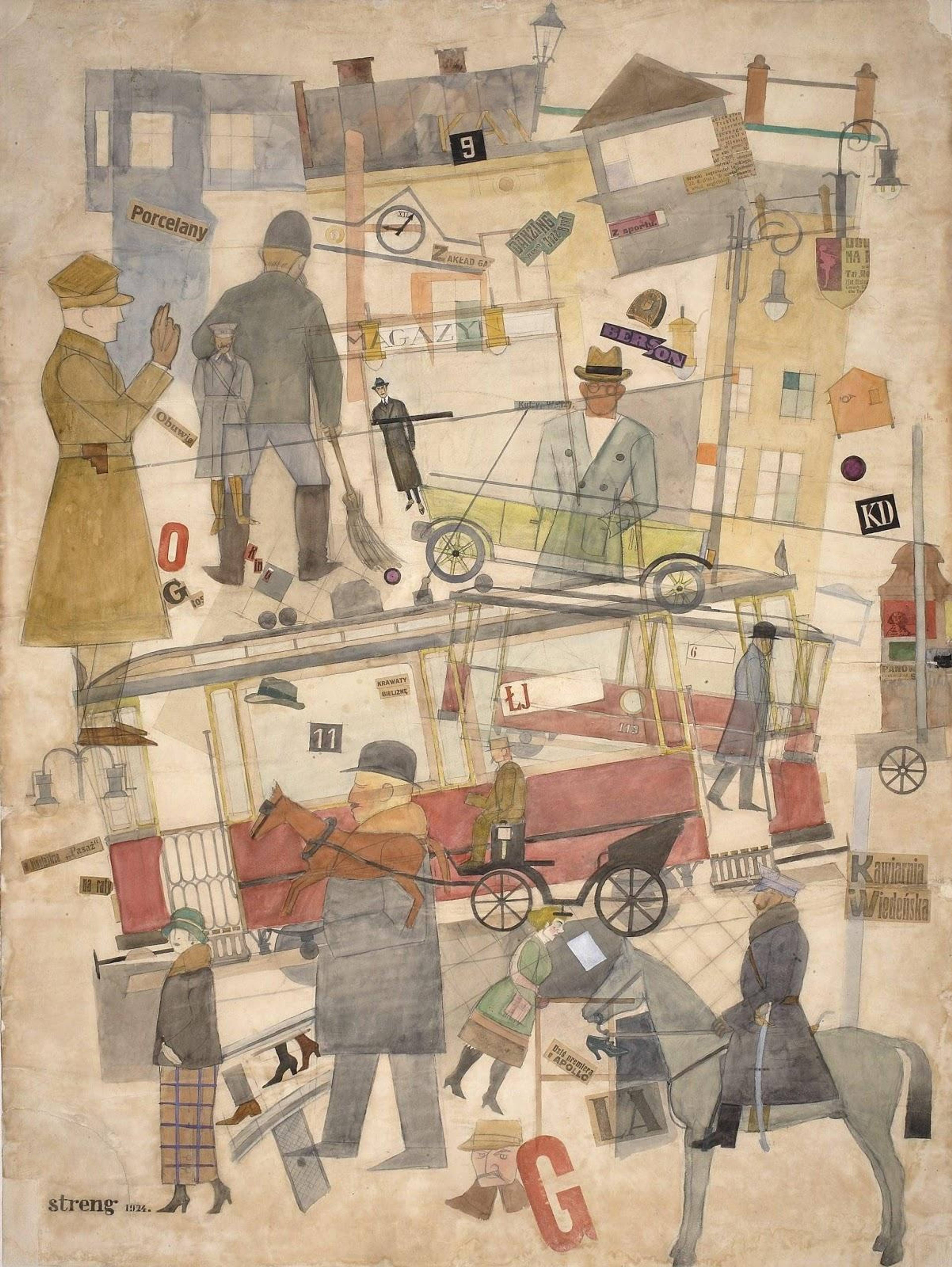

Marek Włodarski (Henryk Streng), Ulica (Street), 1924, watercolor, paper, cardboard