Where to begin? It’s New Year’s Eve. Dinner at a film director and an art director’s place on the Upper East Side. Roast lamb and Salad Olivier. You ask the girl sitting next to you what she wants from this year. She says she wants to make a lot of money. So does the person sat next to her, and the next person along too. This wasn’t what you expected to hear in a pandemic: that everyone planned to get rich. She’s going down South to work the strip clubs, and they’ve both become Robinhood traders.

The ball falls in Times Square. The clock ticks over. It’s a bright new year. Your ex-quant friend drives three of you down to a millionaire’s TriBeCa coke loft in his vintage red Alfa Romeo. You’re racing down Broadway with the top down and all the lights turn green for you, they glow for you. The loft’s full of artists and artworks. The evening’s hosted by your friend who used to be a designer at Celine and now couriers drugs. Plates of lines are going around. You’re handed some ecstasy, you’re talking to a Marxist on the floor, you’re introduced to a former America’s Next Top Model contestant, you’re accelerating. It’s 2021. Cryptocurrency’s exploding. DeFi (decentralised finance) in particular. Robinhood traders on r/WallStreetBets nearly take down a hedge fund. It’s Valentine’s Day and you’re alone. The European Central Bank tweets, “Roses are red, Violets are blue, We’ll keep financing conditions favourable, ’Til the crisis is through.” Cryptocurrency’s exploding again. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) in particular. The Nyan Cat meme goes for $590,000. The “ape in a fedora” CryptoPunk goes for $1.54 million. An animated gif of Trump’s bloated, naked corpse by someone called “Beeple” goes for $6.6 million, setting a new record for any Millennial artist, dead or alive. Christie’s launches a two-week sale of one of his works. It closes tomorrow and has already broken the record again. Current bid: $9,750,000. The US senate passes a $1.9 trillion relief bill. You’re in Starbucks following the floor stickers that tell you where to stand, looking at the price of each cookie, mind RACING, worrying, thinking, Hyperinflation! Michael Burry is right!

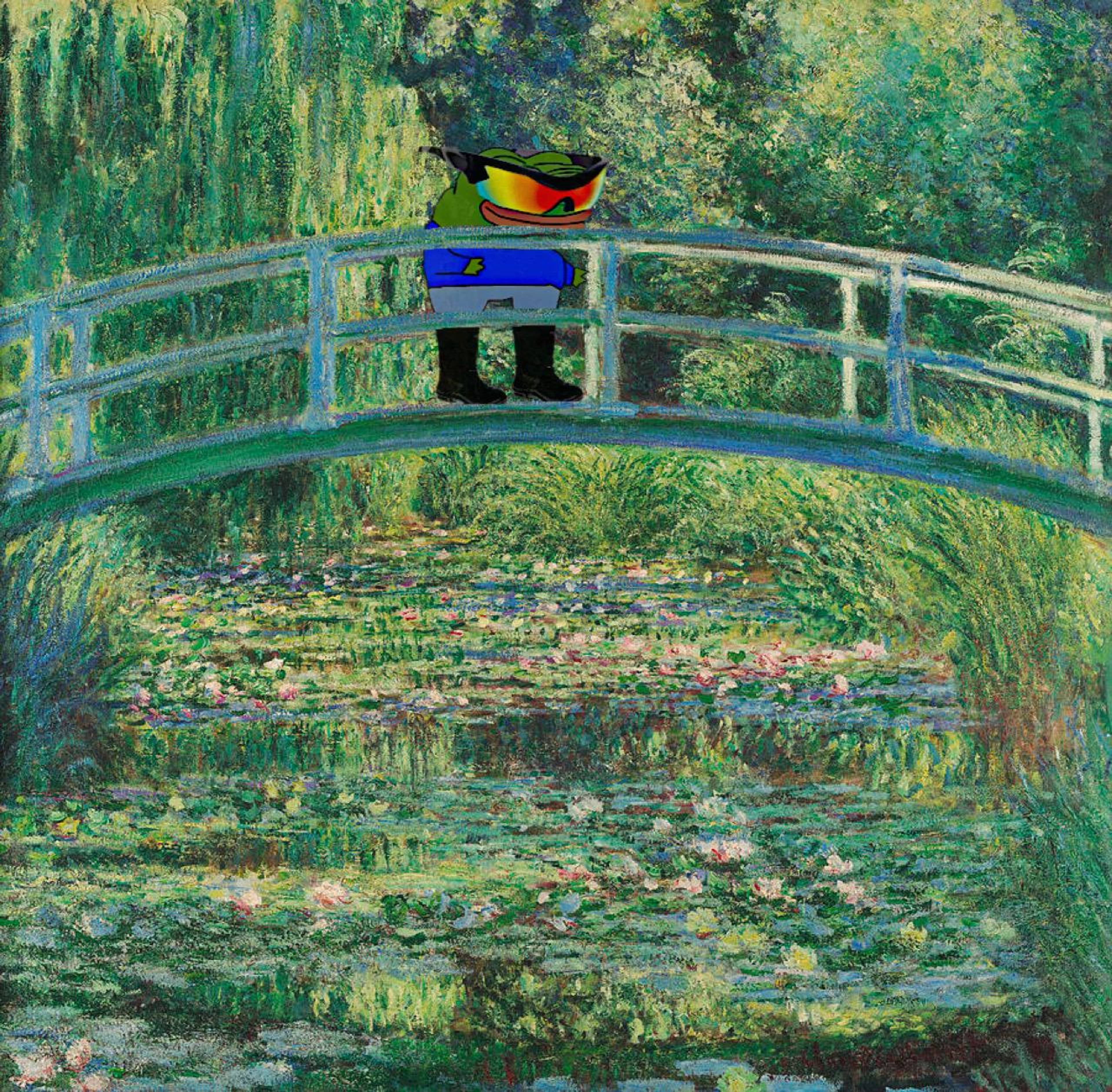

Meme by Anastasia Davydova Lewis

Five stylishly dressed teenage boys stroll down Prince Street extolling the US dollar’s hold over the Swiss economy. A whole other economy based on trolling, memes and network effects is appearing. Now everyone’s a day trader, everyone’s a drug dealer, everyone’s an art director for a weed delivery service, everyone might be the next top model, everywhere’s a secret coke loft, now everything can be traded or shared online; money printer, bad figurative painter, subreddit, museum gift shop, NFT minter go brrrr; it’s the first day of spring; it’s Beeplemania; images and capital have become the same thing; welcome to the total financialisation of reality!

“(Splits Adderall begrudgingly) Is the NFT soul discourse a valid thought experiment”, asks filmmaker Charlie Curran, “or the symptom of a culture industry … enviously not understanding money dreaming up the wildest asset they can imagine pumpable?”

Before Christmas, the only uncertain-times-era art world innovations I could think of were online art fairs and anonymous Instagram callout accounts. Now more innovation has arrived, and it’s come from outside, from the spheres of online culture and cryptocurrency speculation. Crypto has its origins in a mistrust of authority in various forms, from government-backed fiat, to the banking system, to the financial industry. Now it’s also challenging art world elites.

With NFTs, we’ve made another leap from art that’s easy to post, to art that simply is the post.

The old gatekeepers have been losing their power for a while now. In his New York Times profile of KAWS (Brian Donnelly), who’s just opened a major retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, Michael H. Miller writes, “One art reporter told me … that certain directors at Gagosian, the largest and most profitable gallery in the world, would automatically move anyone known to own a KAWS down on their waiting list to buy something.” Nevertheless KAWS is unstoppable. He has his career-defining homecoming museum show, his Peter Schjeldahl writeup, his many pages of coverage, his giant sculptures looming over Manhattan’s Park Avenue and Brooklyn’s Greenpoint waterfront, and, a couple years back, in 2019, he shocked the art establishment when his painting The Kaws Album (2005), a remake of The Simpsons ’ remake of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover, sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for $14.8 million. Images and sculptures are accruing value in new ways: KAWS came up making street art and toy collectibles, and Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) made his name through Instagram and concert visuals. They symbolise the return of populism to the arts. I recently wrote for the Spectator about the trend of bad figurative painting that occupies the bardo between content and art: paintings that are easy to enjoy, and also to post. With NFTs, we’ve made another leap from art that’s easy to post, to art that simply is the post.

The old ways of valuing an object at auction (backdoor dealings, price fixing, and clandestine, corrupt practices) are coming up against the new ways (wild speculative mania and hyperstition) and falling short, for now. Beeple and KAWS, who have dominated the year’s artistic discourse, are outsiders that made it to the top. But it’s a very boring sort of outsider art, made by nerds for other nerds; unlike all the fantastic outsider art made by the unknown and institutionalised, by the visionary borderline-paedophile hermaphrodite fetishists working as hospital custodians painting watercolours through the night. Although, Donnelly does collect Henry Darger.

Lately artworks have begun to look more like memes, while memes have begun to look more like artworks. The memes look nicer, and offer more hope.

So much of today’s culture is a poor-quality remake of something better and more compelling. KAWS bootlegs pop-cultural staples like Mickey Mouse, the Simpsons, Peanuts, and SpongeBob in his own depressive comic style, while Beeple takes Mickey, again, Pokémon and Shrek, plus politicians like Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton and Kim Jong-un, and composites them into dystopian CGI montages. There are two paths for the golden-age American cartoon star: to be withdrawn, like the lascivious skunk Pepé le Pew, or, worse, to be reimagined as bad art, as childish and nostalgic art for those that don’t like ideas, or beauty.

Lately artworks have begun to look more like memes, while memes have begun to look more like artworks. The memes look nicer, and offer more hope. Consider Pepe in Giverny:

"Don't speak to me about "Claude Monet," worm, I'm a graduated art teacher. I'm not saying the jpegs or videos aren't art, I'm saying your whole system is a mere pretence of an art scene for profiteering by platforms and crypto moguls." Art by Tyom Trakhanov

There’s just too much of everything. There are too many different Oreos . 65 flavours in 8 years is too many. Too many Hot Chicken Wing Oreos, Waffle & Syrup Oreos, Jelly Donut Oreos, Supreme Oreos. There’s too much content that appears different but is the same. Too many identities are available to us. Too many manias. Too many hysterias. Examine nearly any aspect of society and you can see it’s gone too far. The reason so many flavours of Oreos are invented, according to the cookie’s brand director, is that this overabundance of choice reminds us of and drives us back to the original. It reminds us of how much we like the old Oreo, the Platonic ideal of the Oreos of childhood, the Proustian Oreo with the glass of cold milk. When there’s too much of everything however, at some point the original is lost, the memory is lost, and all that remains are faded, flat, hollowed-out derivatives.

On the wall of Winkelmann’s studio are two massive TVs. One shows Fox, the other CNN. They are never turned off. It’s an admirably nightmarish way to work: networked into a terrible matrix of the doomsaying now; making images inside of two flashing American propaganda images, a devil on each shoulder; caught in the mise en abyme . His mediaevalesque scenes of pop culture gargoyles and demonic politicians with mutating cyborg bodies are images of images, of the pictures of the world we’re shown on the screens that surround us: the collective-hallucinatory firmament in which tired art, recycled pop, bad taste, political spectacle, and hyper-speculation swirl and coalesce into modern life. I walked past a car by Washington Square Park the other day in which the owner had painted in their window, “RBG lives.” But what does this mean?

Beeple, Crossroad, 2020

Beeple holds a mirror up, without insight or criticality but with an unnerving feel for the contemporary grotesque, to our sci-fi present, in which stars of news and entertainment culture have taken on a messianic quality, with politicians, justices and comic book characters revered like saints. KAWS reflects what Max Lakin, covering his show for the New York Times , calls “a totalizing machine of flattened taste, where cartoons and artists are interchangeable content to be printed on everything.” They lead a triumphant procession of popular things. But as someone who grew up hating popular things, who turned to art as a child because I felt alienated by popular culture, my classmates, the country I was growing up in, society, and so forth, I can’t feel happy about that.

Though, if I’m honest, just before Christmas, wandering through Midtown one night, I stumbled across KAWS’s 20-foot tall antacid-pink BFF (2020) in the illuminated lobby of 280 Park Avenue, behind Grand Central Station, and did have a moment with it, and did feel overwhelmed by its size, its radiant blankness and its perfectly fabricated sheen, and I did leave the great colossus full of festive cheer. In Los Angeles they say, “Life is like a movie.” Here in New York it’s like a weird exhibition.

Ever look in the mirror for too long and start thinking like, Damn I’m really a human being. I’m really in this bitch. KAWS, BFF (2020)

“Kings of Leon to release new album as a non-fungible token” … “Beeple brings crypto to Christie’s” … These are among the most anti-aesthetic headlines ever written. The poetry of a dying civilization. As outsider art historian Mónica Belevan has noted, of the latter’s image of the death of Trump, “This is post-political, read as post-orgasmic: post-passion, post-death, post high-stakes. It is the tablescraps of tablescrapping. You can tell because the market has no problem metabolising it: there is no resistance to build if there’s no conflict.”

The most popular series of NFT collectibles are algorithmically generated. And what they reveal, compared to the rest of culture, is a broader and more prevalent trend of art and entertainment that has the uncanny feeling of having been made by algorithm, even though it wasn’t. A painter and performance artist once told me, in the brutalist basement of the old Met Breuer, that Future had destroyed the future. Trap music has taken over the world, and it all sounds more or less the same now. It might be amazing, but it sounds the same. It’s supposed to sound the same. That’s the idea, what makes it so powerful. A talented producer can make a song in ten minutes on a live stream. A talented producer can make a song in less time than it takes to listen to. It’s never been quicker to write a song than now. Songs keep getting shorter and shorter. Records keep getting shorter and shorter. It’s a numbers game. I can write these columns pretty quickly now. This is an age of great speed and competition. We’re all looking for more popularity, new ways to find an edge; and yet, all this competition only seems to lead to blandness and mediocrity, rather than breakthroughs. Nor does it lead to collapse; even accelerationism doesn’t work. We want too much content, too fast, and it just leads to this endless algorithmic churning, this paint-by-numbers effect. You see it in art. In Netflix documentaries. Spotify playlists. Op-ed pages. The news. The latest manufactured outrage. Well-reviewed first-person novels about nothing. All so dreadfully banal and repetitive. This is what results when everything is forged in economies of dollars, of ether, of attention. Most culture now has the feeling of having been made by algorithm; and the reason for this, is that humans have begun to act like algorithms.

Lucy, a chimpanzee, was born in America in the Sixties. She was raised by the psychotherapist Maurice K. Temerlin and his wife Jane in their home in Oklahoma. She was raised to believe she was a human. Locked down in their house, she took to drinking gin, reading Playgirl , pleasuring herself with the vacuum cleaner, and, something all content producers will be able to relate to, sculpting maquettes of human heads out of her own shit. Today, like a chimpanzee that thinks she’s a person, we have collectively begun to act like something other than ourselves. We’ve voluntarily assumed the logic of the systems we’ve created, and organised our lives around them. We live in an algorithmically generated culture, and we are the algorithms.

Chad NFT art enjoyer

Poor images like Beeple’s, or the $1.54 million ape in a fedora, or most everything in the stream, are lessons in why we can’t stay locked down forever. Can’t just stare into our screens until death. Because if we do, we’re abandoning Earth, the possibility of transcendent beauty, and with it the sanctity of human life, which is given meaning by powerful art, among other things. We’re eating our own souls. Poor images like these are images of hell.

What non-fungible (which is to say, unique) tokens show us, is the absolute fungibility of culture today: its hazy, interchangeable meaninglessness. How it all belongs on a blockchain. How it all belongs on an infinite self-generating playlist ouroboros. It all belongs on a streaming service that slowly steals the hours and the heartbeats from inside you. When you look at the Discover Page Hotties, you look back into your own soul through a clouded mirror. “Online,” a mysterious anonymous cipher writes to you, “so much is dependent on an algorithmic matrix of mined data that the user’s identity is distilled so accurately that you can’t breach the identity that’s fed back to you via the screen. So no chance encounters, just a recurrent overlap of what you already are.” If life was once about chasing after a dream, it’s now about running away from the comfortable, hypnagogic lifestyles prescribed to you by the culture we create together, reflexively and imitatively. You’re living inside other people’s dreams; and these are not good dreams. So much of modern life is algorithmically scripted so as to exclude surprise or chance, and you must try to break free of this script every day. Rejecting all this post-death culture is a good place to begin. It’s New Year’s Eve —

Spiderman French Wojak meme