I first heard of Midjourney at the lifestyle influencer Caroline Calloway’s leaving New York party in spring. As it turned out she was having a leaving party every night that week and inviting different groups of guests to her dark and cosy West Village studio apartment, which was by then close to full of empty or half-drunk bottles of wine and vases and coming-apart bouquets of flowers and candles melting all over the place. The bath was fragrant and had blossoms floating on its surface like water lilies. There wasn’t anywhere to sit and not enough wine glasses, and we were made to drink out of stranger and stranger vessels, our host kept handing us longer, pointier and more unwieldy ceramic and glass objects from which to sip. A software engineer called Duncan, whom I’d just met that evening, began to tell me about an invitation-only Discord server he was involved with, where images could be conjured simply by typing in a brief description; some artists we knew were part of it as well, he said, and were playing with this in-development software in this half-secret server, rendering images and experimenting in its channels. It was one of those evenings when you have the feeling of reality melting all around you.

Like an old mystic visionary watching the fire, believing that eventually a figure will make themselves known there, the program finds the messages it seeks in the smoke.

Midjourney, and other text-to-image generators, like OpenAI’s DALL·E 2 and Google’s Imagen and Parti, allows those with early access to quickly and easily call forth complicated computer-generated imagery with simple text prompts, and, if you like, image references too. All of these artificial intelligences (AI) are learning the linguistic relationships between pictures and their descriptions, and learning also how to images by a process of “diffusion”: they start with a random noise pattern of coloured pixels, look for recognizable aspects of the image they’ve been instructed to find there, and keep clarifying it into variations of that image. They work by first destroying their training data with successive layers of visual noise, and then by learning how to undo that process and recover images from the noise. It’s a kind of pointillism in reverse; rather than beginning on the l’Île de la Grande Jatte on a Sunday afternoon and then separating that scene out into 220,00 or so tiny dots of paint over a couple years, as Georges Seurat did, the AI begins in the cloud of diffusion and looks for the form and the content. Like an old mystic visionary watching the fire, believing that eventually a figure will make themselves known there, the program finds the messages it seeks in the smoke.

It’s a uniquely literary approach to image-making. Rather than trying to create images in the minds of your readers, or record sights you’ve seen in words, you attempt to conjure new images in the mind of an AI. You have to learn to describe something that may not exist, and to do so in language that’s tailored for the machine, that it can parse. It’s a radical jump from one form of creativity (writing) to another (computer-generated imagery), and, for a writer such as myself, unusually satisfying and immediate.

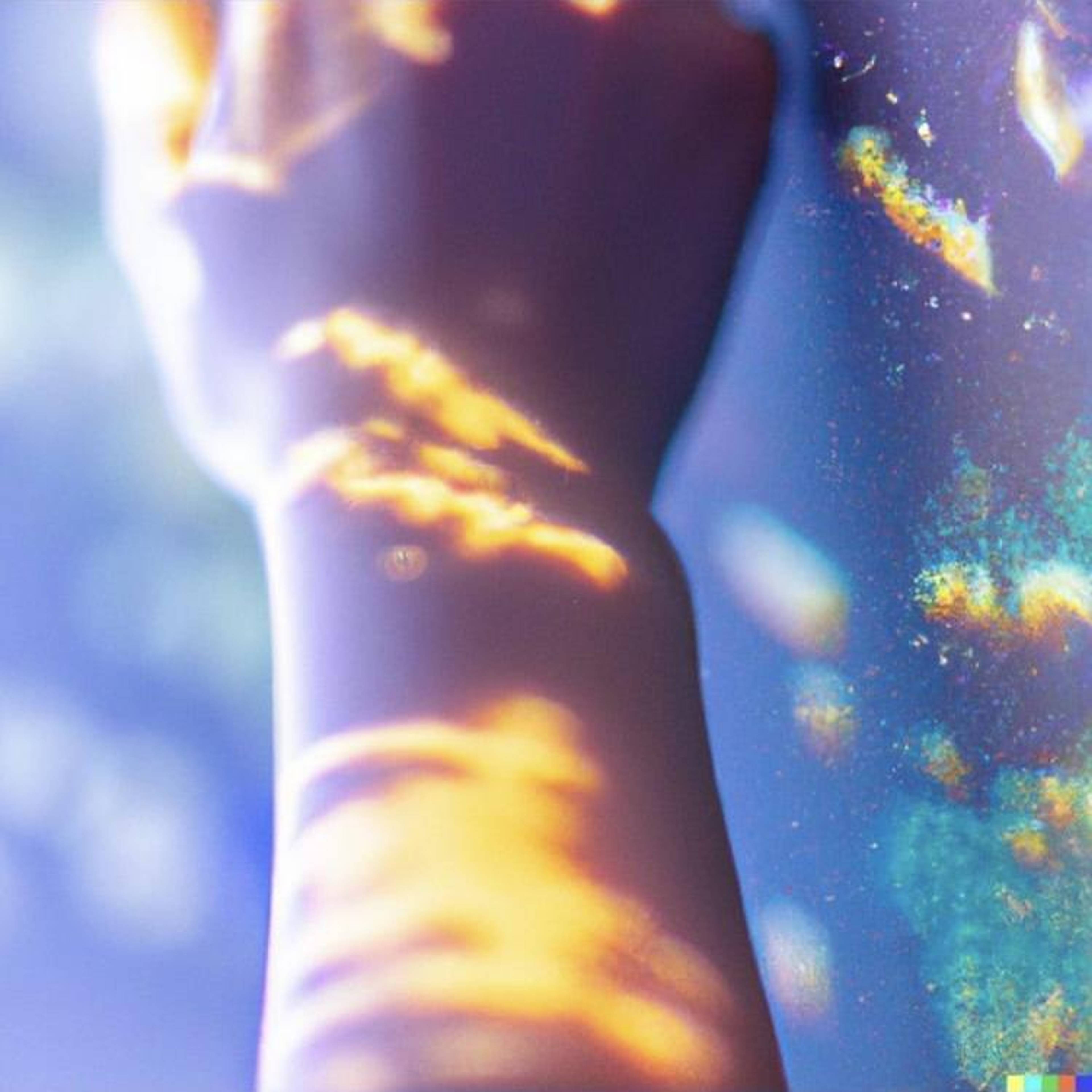

Image of hand, made by Gray Crawford with DALL·E 2, 2022. Source: https://www.instagram.com/graycrawford/?hl=en

Text-to-image AI is trained not to make photorealistic depictions of real people’s faces, which means it’s a form of photographic technology that doesn’t allow for selfies. We cannot place ourselves at the heart of these images: we are not the subject matter, and nor is our emotional subjectivity creatively expressed. The images it makes are neither copies nor originals. It’s not like a camera that can reproduce the world outside, but also cannot be straightforwardly coaxed into expressing how you feel inside, because most of its aesthetic choices are decided by algorithm and chance.

These images seem to come from someplace else, another dimension. The AI is a cognitive system that learns how the world appears through the hundreds of millions of found images in its dataset; a vast collective memory formed of images we’ve produced, the visual realm that we have created as humans. While it does work from photographs, it also works from artworks and illustrations and other sorts of visual information, all of which are weighted equally. It sees without a point of view. The images it makes don’t point to any one particular reality, but rather to many, many disparate sources joined together, all of which are themselves representations. Its composition points in so many different directions at once, and could be compared to cubist painting; but rather than seeing the same subject from different angles and moments in time simultaneously, we see different instances of the same subject-category gathered and composited together.

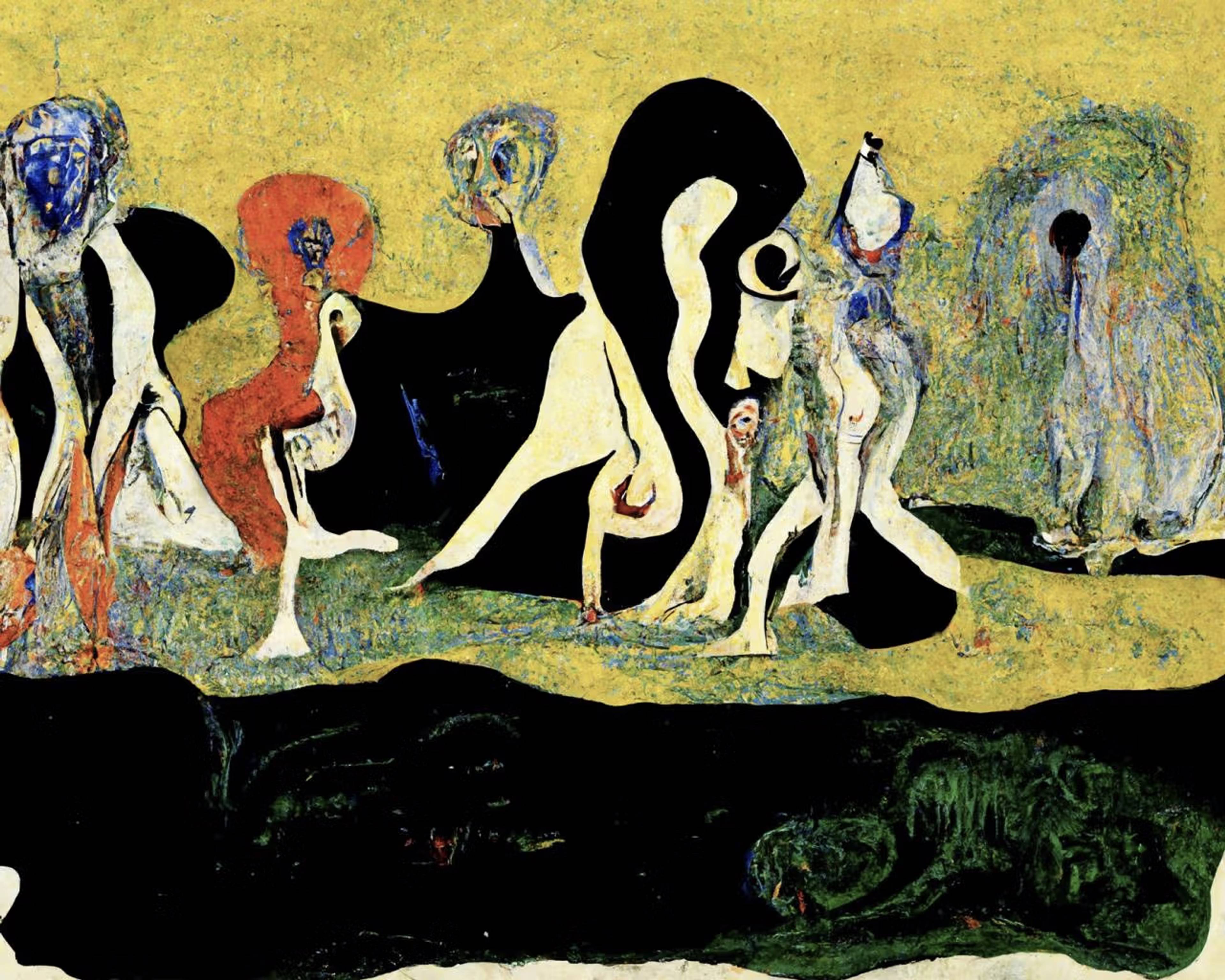

Image of nighttime ceremony, made by Honor Levy with Midjourney, 2022. Source: https://www.instagram.com/mo_0dboard/?hl=en

In their recent essay “Infinite Images and the latent camera,” artists Holly Herndon and Matthew Dryhurst go through of some of their own experiments with DALL·E 1 and related software and suggest that “these tools will soon contain all the elements necessary to produce limitless resolution compositions guided by language and stylistic prompts.” It will soon be possible to make images that tend towards infinity, composed from a sprawling Borgesian labyrinth of referents. For now, they show the example of Charles Guilloux’s landscape L’allée d’Eau (1895) expanded outwards beyond the constraints of its frame by DALL·E. When I visit museums, I often wish to step inside old paintings, and experience the times and places in which they were made; that remains impossible, but those paintings might now be extended to the horizon. A favorite painting could be grown to the size of a museum, or as far as the eye can see.

An artist’s oeuvre can also (if we set aside questions of authorship and authenticity) be added to by automated imitation now, and Herndon and Dryhurst propose a term for this: “If sampling afforded artists the ability to manipulate the artwork of others to collage together something new,” they say, “spawning affords artists the ability to create entirely new artworks in the style of other people from AI systems trained on their work or likeness.”

With good written prompts there’s a way, perhaps, of pushing kitsch so far that it becomes something strange and alluring, even moving.

In this age of repetition and mimesis we endlessly remake the past. Even our cutting-edge AIs are trained on the past it seems, and are in a sense conservative in their approach (they’re trained on historical imagery, their datasets are censored, and sexually explicit, violent, or otherwise provocative prompts are forbidden). The images they make are “kitsch,” according to Clement Greenberg’s definition: derivative examples of low, popular culture that feed off of “the availability close at hand of a fully matured cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions, and perfected self-consciousness kitsch can take advantage of for its own ends.” They are imitations of life. They are imitations, often, of art and its effects. Their beauty, when they are beautiful, comes about by chance rather than purpose. These machines are trained to compose images objectively, so that even styles of expression might be reproduced mechanically and indifferently. Some leading research laboratories are developing the ability to program (imitations of) styles, to appropriate different artists’ styles as materials, and even to combine them. Mannerist artifice is blended with artificial learning. With good written prompts there’s a way, perhaps, I hope, of pushing kitsch so far that it becomes something strange and alluring, even moving.

Image of painter, made by Holly Herndon and Matthew Dryhurst with DALL·E 1, 2022

This picture, made by Herndon and Dryhurst with DALL·E, reminds me of the New Leipzig School painter Neo Rauch: it has a similarly social realist style, and bizarre and mythical-seeming content, and is likewise rendered with a distinctive lack of joie de vivre. Most images made by AI have this unnerving lifeless quality, this uncanny valley feeling of neither depicting nor having been made by a real person. It’s this lifelessness that makes them compelling to me. Their weird and unintended abstract qualities give them a new aesthetic, at a point when new aesthetics are so hard to find.

AI can be used in subtle ways, to add a wash of unreality to images. In the exhibition I’ve just opened in New York, Ezra Miller uses images generated by neural networks to create abstract textures, color palettes, and uncanny landscape photographs; which are in turn used as source material for his own real-time generative painting simulation, Imago.

Ezra Miller, Imago, 2022. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

It can of course be used in much less subtle ways too. Figures drawn with Midjourney (the only AI I’ve tried out for myself) tend to come out as tortured and deformed as Francis Bacon’s. The program still has great difficulty orienting objects in space, or making their fragments cohere. It cannot put reality back together again. The tears in its illusory world are plainly there to see. But when I first began trying it out, it gave me a feeling of vertigo and awe. It would be very difficult for a person to make images like these on their own. We were born on a planet where most things were made by nature, or human consciousness, and are now crossing into an age in which more and more of our surroundings will be made by, or in conjunction with, artificial consciousness.

Eventually, the machines might learn what we desire to see, through the choices that we make from the variations we’re offered. They could be a new kind of tool that learn as they go. Or they could surprise and confound us. Over time, with so many prompts, variations, and choices, with the AI ever transforming, we could make together some genuinely unusual and unexpected images. We might get there very quickly, we might reach convincing photorealism and painterly deepfakes very soon and break right through, as the modernists did with painting, into novel modes of abstraction and surrealism, or the digital sublime. This is an aesthetic in its infancy. Midjourney, DALL·E and the like are particular ways of approaching it; but a talented coder could write their own AI and train their own virtual apprentice to chase after whatever aesthetics, techniques, or concepts they like.

Image of seraphim, made by Jon Rafman with Midjourney, 2022. Source: https://www.instagram.com/ronjafman/?hl=en

The possibilities of AI visuals go far beyond text-to-image also. For his ongoing series of “mental image” works, first shown in his exhibition “UUmwelt” at the Serpentine in 2018, and now in his online show “Of Ideal” with Hauser & Wirth, Pierre Huyghe asked his volunteers to look at or think about an image while having their brains scanned inside a magnetic resonance imaging machine. Then, using AI software developed in collaboration with Kyoto University neuroscientist Yukiyasu Kamitani, Huyghe attempted to decode the activity in their brain and render it back into images of whatever they were looking at or thinking of. It’s a very different approach than text-to-image, but both are attempts to move ideas directly from the imagination to an image on a screen. It’s a great leap to make, and a very different way of thinking about creation. Someday, it might even be possible to have your subconscious, or your sleeping dreams, rendered as a stream of images with the help of artificial consciousness; allowing for entirely new approaches to surrealism, and automatic writing.