There was nothing to complain about at the fair this year. Nothing to make fun of this year. Tuesday afternoon I was in the Javits Center, which is now a vaccination center run by the US military. After my shot I sat down by the exit, where a harpist and clarinettist played Satie’s “Gymnopédies” on a small stage. There was a selfie wall too, where strangers were crying with joy (?).

That evening I went to a new rooftop bar, Happy Be, for a party for Nate Freeman’s column “Wet Paint”. “The Art Party Circuit Comes Roaring Back at Frieze New York,” said the Times. No rooftop bars offered to throw a “Downward Spiral” party, but New York is opening up again. Wednesday I went to the Swiss Institute dinner at Kafana for Jan Vorisek and Sandra Mujinga’s shows, where curator and soon-to-be Piedmontese gallerist Saim Demircan spoke to me about how Ballardian Hudson Yards, the riverside development the fair has just moved into, is, and how it makes visitors wish to kill themselves. Thursday was dinner on the terrace of Balade with a group of yuppies, young crypto millionaires and creative directors, where I learnt, among many other things, that it’s Ryder Ripps’s teenage brother who’s been plastering big photos of his face all over town with the caption, “This CHILD Made OVER $1,000,000 Selling NFTs [Crypto]. Click Here To Find Out How.” The city’s entrepreneurial spirit has returned. I met a nice model-turned-cryptographer, who walked into the restaurant then turned right back out again, having forgotten her mask. “We’re all mask slaves now,” she said widening her eyes like saucers. She rummaged in her handbag in the darkness for a mask. We thought she’d found one. “This is a hair tie,” she said.

Street campaign for Million Token Website

The early 20s multimillionaire beside me said he didn’t understand why so many of his multimillionaire friends were investing in immortality. We spoke about a house full of blood-boys. The next day I went to Frieze with my SARS-CoV-2 test results, my driving license, my QR code, and my barcode; and then to an artist’s house party in Chinatown, which was the unofficial Frieze party. On my way home I popped into the Zoomer whales’ party in their SoHo loft, but left right away. It was too late, my friends had moved on. Saturday I went to Precious Okoyomon’s Performance Space dinner at Creator House, where I was seated at the end on the kids’ table, surrounded by young and ethereal LGBTQ+ actors and models, it girls, radical experimental librarians; I don’t know why I was sat at that table. No one seems to wear a bra these days. No one wears opaque clothing anymore. Along the table they were taking molly. A recently appointed gallery director, the talk of the town, came over and said he’s all about beauty. “Beauty is the only form of morality,” said one of the ethereal beings with flaming Pre-Raphaelite hair.

The artists Downtown are getting high, they’re complaining about publishing houses, and graphic designers, while the Bridge and Tunnel crowd are all fucking one another upstairs, and that’s just how it is now

The secret service were stationed outside. At parties in Manhattan now they’re always stationed outside. One girl had run away, her friends were looking for her. “When I found her,” they said later. “She was so sexually hungry. I had to run away. She was on tooo much molly.” There’s a certain mania in rooms like these that’s quite refreshing. “At one point the secret service wouldn’t let me in lol,” said Precious. “I was locked out of my own party tragic lol. They know I’m a danger to the government.” I left to appear in a fashion shoot for a Parisian house, why call time was 10:00 PM, and afterwards, on the way home, popped into the famous coke loft, which was overflowing with artists, novelists, a Spike contributing editor. I left. When we were all kicked out, I left. I walked home and felt glad that I’d made it to Sunday.

There was a sex party on the other floor. “This is what I heard from someone”, a friend said. “A whole slew of people seemed to be leaving the same time our floor got kicked out, but we hadn’t seen them all night; Dazed, kind of satisfied looks on their faces.” The city reopens in seven days. “Ohhh there is a sex party on another floor most weekends, yes,” another friend said. “I’ve been it’s gross. Bridge and Tunnel types,” she said. “It’s a straight people thing.” The artists Downtown are getting high, they’re complaining about publishing houses, and graphic designers, while the Bridge and Tunnel crowd are all fucking one another upstairs, and that’s just how it is now. Have you noticed how loosely this term “sex party” is used nowadays? Maybe you haven’t. I went home and slept, it had been a long week. My life is a shambles, I have to pull myself together. I don’t recommend taking the vaccine and joining the art party circuit (not medical advice). Now I have the Pfizer flu and I feel crazy, delirious, shivering, like my mind is melting, I keep buying McDonald’s strawberry milkshakes, here are my fever dream thoughts.

When I’d imagined what an art fair might look like, after the Event, I saw stern blondes in sharp-angled black suits striding round shilling NFTs from tablets. But it wasn’t like that. There was hardly any computer art, just lots of abstract painting and some figurative painting too. Some drawing. It was all so gentle, and mellow. So pleasantly soft and relaxing. A museum of what critic Rob Horning has described as culture without friction: “‘readable books’; ‘listenable music’; ‘vibes’; ‘ambience’ etc.” You can tour the whole fair in an hour or two. There’s art that’s easy to look at, and nothing more. It does suggest a return of art for art’s sake; a return, as they said over dinner, to beauty.

This year’s Turner Prize shortlist, which was also announced last week, stands against beauty however, against art for art’s sake, individualism and self-expression. Last year the prize was cancelled completely. This year, no artists made the shortlist, only five collectives with social practices. Speaking to the New York Times , Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson explained that his jury hadn’t chosen any artists because there hadn’t been a lot of art to see last year. “Clearly, there was so little to see with the lockdowns,” he explained. This is astounding, for the director of the Tate to say there wasn’t much to see: That’s because you didn’t put anything on! Because you didn’t come up with new ways of sharing art with the public during a crisis! Even though it’s your job to do so! I feel like I’m hallucinating. For a jury of directors of major art spaces to say that they’re not nominating any artists because there wasn’t any art to see is self-serving, cynical, boring and pathetic. “Even our museums are now terrified of art – too stunted for aesthetic engagement, too scared to model life beyond the lowest plane of utility,” wrote the paper’s critic Jason Farago when the shortlist was announced. “We are going to be social workers, and ‘art’ will be our excuse for doing social work badly.”

Under New Labour, in the late 1990s and the 2000s, British culture tzars came to see art as a panacea for society’s ills; they’ve since come to see panaceas for society’s ills as art.

Having failed to find ways of connecting with the public during the global existential crisis, when everyone was trapped at home with nothing to do, and death and eternity resting heavy on their minds, the jurors have now turned to groups that were able to: like Gentle/Radical, which collected stories of lockdown and brought them to neighbours’ doors in Riverside, Cardiff, Project Art Works, which organised film screenings and installations that could be viewed from the street in Hastings, and Black Obsidian Sound System, which threw a 24-hour rave online. (My friends and I didn’t receive a nomination for the exhibition we organized in a West Village park, although it was well received and written up in ArtReview , or for the parties we had on street corners.)

Over the past century high art has swallowed every other cultural form (avant-garde dance, theatre, poetry, literature, cinema, pornography, stripping, online abjection, ritual sacrifice, crucifixion, cannibalism, Thai cookouts, long-distance sailing etc.) and incorporated them back into itself. Now it’s swallowing social and political forms too. It has been for decades, but now more cynically so. Protests against institutions were the big story of art in the 2010s; however there’s a great difference between organizing protests against institutions, and restaging localised activism as ambient feel-good content for institutions and art prizes, as political furniture music. Grassroots collectives are ushered inside the museum walls by the gatekeepers, who wish to cleanse their souls and alleviate their guilt, or perhaps just to make up for their own inability to respond to a crisis. Under New Labour, in the late 1990s and the 2000s, British culture tzars came to see art as a panacea for society’s ills; they’ve since come to see panaceas for society’s ills as art.

This is the new world of floating signs and symbols, where everything must become a token

The Turner Prize shortlist suggests a contempt for art and for artists that most of us can well sympathize with, nevertheless I do think its jurors have a responsibility to find good artists and advocate for them, or, if they really insist, to find good socially engaged collectives and advocate for those. However, if only socially engaged collectives are nominated, each of them is belittled, undermined and reduced to a supporting role in a publicity stunt by the jury: You’re not here because of what you do for your community, you’re here because of what you represent for us. Like much else today it’s both patronizing and unbearably literal. This is the new world of floating signs and symbols, where everything must become a token: in the fair, hazy paintings are traded as stores of wealth, while on the blockchain, images become speculative derivatives and financial instruments, while in the art prize, diverse community groups are tokenized as fungible window dressing for public institutions that are laying off their staff. As Black Obsidian Sound System commented after their nomination, “We understand that we are being instrumentalised in this moment.”

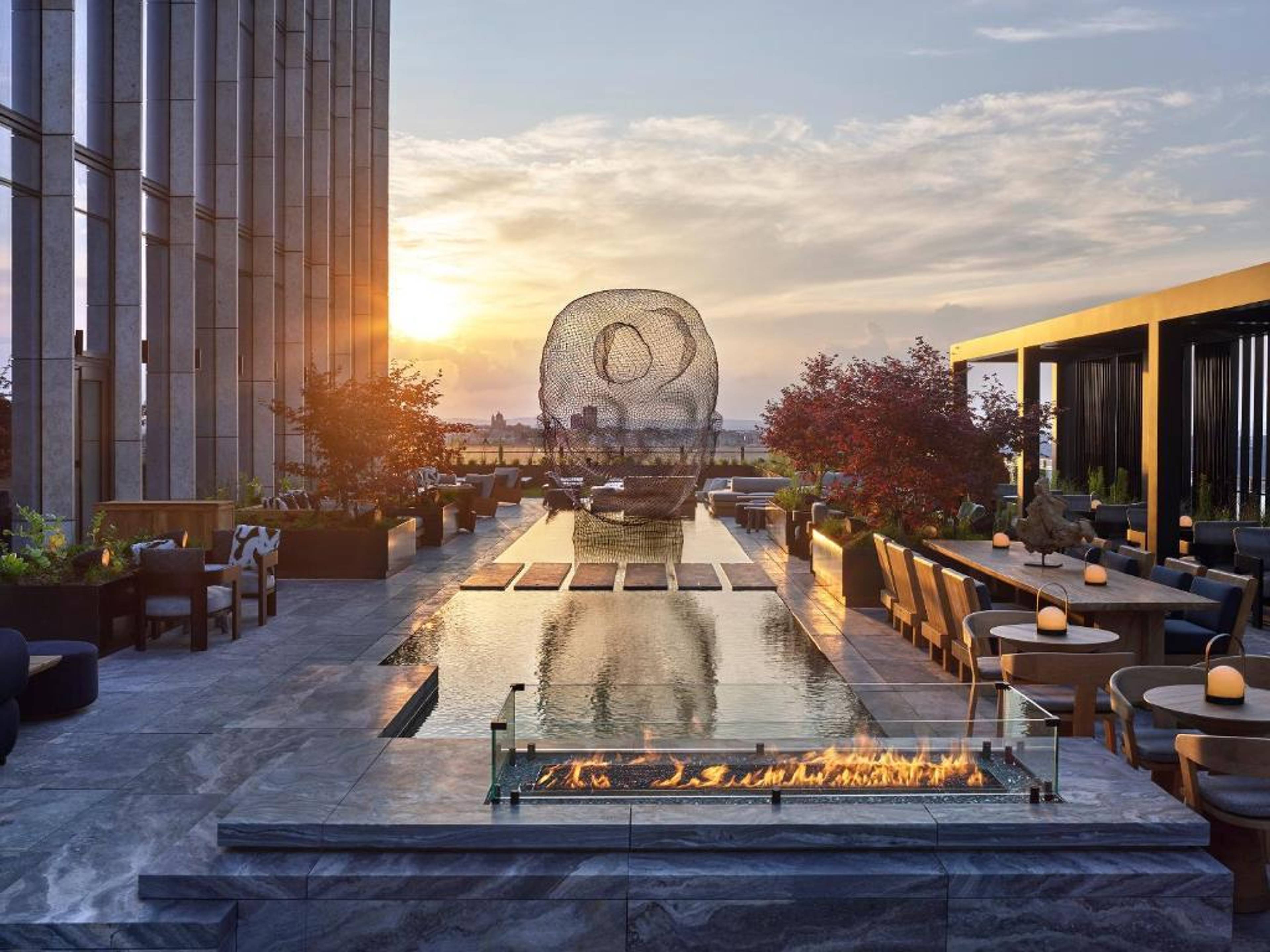

Jaume Plensa sculpture on the terrace of Equinox Hotel. Photo: Collin Hughes

It’s a funny world in which the most expensive artist under 66 isn’t really an artist, the most expensive painting in history is missing, will never be seen again, and the most influential art prize is no longer awarded to artists. Welcome to the dystopian present. In Singapore, MetaKovan (Vignesh Sundaresan) is building a museum in the metaverse, with Beeple’s 5,000 Days as his Michelangelo’s David; in the high-rise enclave of Hudson Yards, in The Shed, the $500 million white elephant with the moving roof that never moves, that cannot be moved (something to do with needing costly sailors to come and rig the curtains), facing the Heatherwick honeycomb which has been closed to the public because people keep jumping off it to their deaths, by the bankrupt Neiman Marcus, under the Equinox Hotel with the giant wireframe sculpture of a person with a hole in their head, the shimmering monumental psychogeographic sunset-facing lobotomy, is a calm, mindful fair where all is mellow; in Coventry, where the Turner Prize has gone to bring art to the reaches, five different socially engaged collectives will be judged against one another, by a cheery bunch of museum directors and actor/ collectors, to see which is best; a nightmare vision of the postmodern welfare state.

These different art worlds are so far away from one another, but are joined by their lack of variety. When I first started to go to Frieze in London it was a bustling, cacophonous variety show packed with different approaches, ambitious gallery stands, architectural interventions, weird projects winding in and out of the fair, bars and restaurants everywhere, and a circus of freaks, interlopers and celebrities clamouring for attention. Regent’s Park was where I had my education, where I went to learn about contemporary art and the gallery scene, and to see what was being made around the world and who the important and the up-and-coming artists were. At the end of each day they’d play applause over the intercom, applause for all the money they’d made and how, and gallerists would lean back in their replica Eames chairs with a flute of Ruinart and light up, weed smoke rising up into the tents. Today though it’s more like a smart weapon, or a duty-free, a targeted, purified space of highly refined middlebrow taste designed to sell a certain kind of painting to a certain kind of person, and nothing more.

Art’s not about feeling good: not for collectors, not for curators, not for artists, certainly not for writers, and not for audiences either

The same’s true of the Turner Prize shortlist. It’s crafted to appeal to a certain sort of person: not to an art-loving public, or West Midlands schoolchildren who might have dreams of escaping their hometown and creating an immortal masterpiece, by which they might transcend this Earthly realm and echo through time, but to fellow professionals wanting to feel good about themselves. But art’s not about feeling good: not for collectors, not for curators, not for artists, certainly not for writers, and not for audiences either. It doesn’t have to offer us empathy or understanding, but it should offer the possibility of change; social change, sure, but personal change as well. Transformation, transcendence, redemption.

Contemporary art’s dominant modes – objects made to appeal to collectors through their aesthetic, and gestures made to satisfy prefabricated moral pieties – are both configured to conform to established expectations, and so are structurally unlikely to lead to radically new ideas. They reflect the self-reflexivity of the day, the logic of the networks, which can only give us more of the same, which continually repeat themselves, and I repeat myself too (say the line): there’s too much of everything, so it all feels interchangeable. The boundaries between things are blurred. We really don’t need any more of the same. You should give the world something nobody’s asking for; yes, you should give the world something that nobody wants.