Last month, I snuck away from my press trip to Sharjah and rode the buses four hours down the coast of the Arabian Gulf to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which floats above the turquoise waters under an ornate metal dome designed by Jean Nouvel. While a great museum, there are hardly any famous works inside, and the one masterpiece that was supposed to have been unveiled last September, the most expensive painting in history, Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, or “Saviour of the World”, wasn’t there. According to staff, nobody knows where it is. At the Louvre in Paris, which is hosting a blockbuster Leonardo exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of his death this autumn, they also have no idea where it’s gone. Since it was sold at Christie’s New York in November 2017 for $450.3 million, to, the New York Times claims, rogue Saudi crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman, it hasn’t been seen. But then, before it was authenticated in May 2008, in a studio above London’s National Gallery, as Leonardo’s lost masterpiece, few had any idea that such a painting existed.

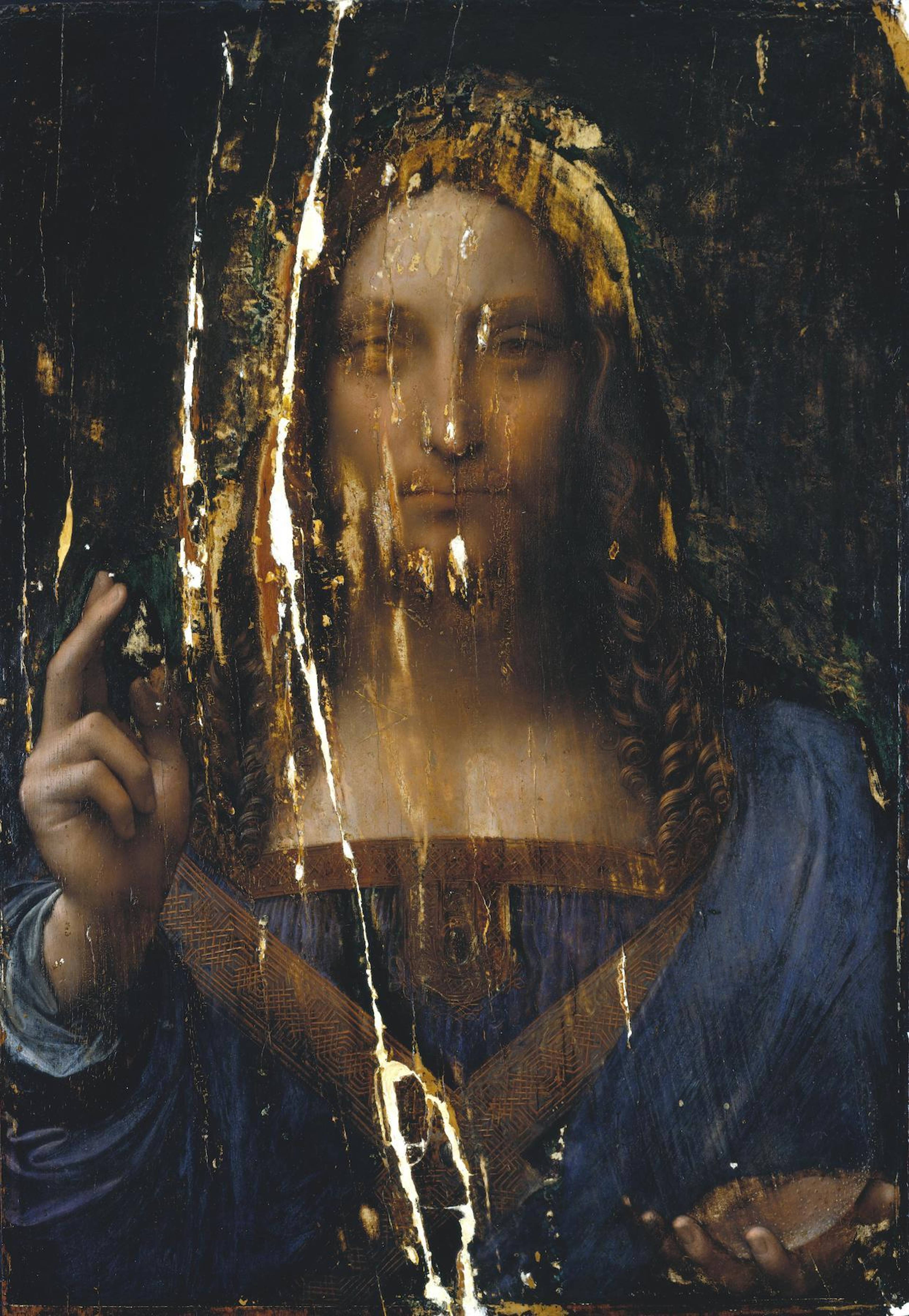

While there’s no need to restage here the arguments over whether it’s really a Leonardo, how weirdly it’s been restored (it looks crazy, like it’s been face-swapped), how it came into the hands of Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev, and how it was sold again, though they’re all fantastic reads, I will say how much I enjoyed the comments threads below the New York Times article, with all of their art historical, geopolitical, high financial and religious conspiracy theories. Few things in today’s culture are as compelling as a good messageboard, and this one feels like a new Da Vinci Code for the collective paranoia and cultural commentary years, written, like Bernadette Corporation’s Reena Spaulings, by more than a hundred different authors.

Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, c. 1500, after cleaning

Many commenting suggest that the painting has disappeared because its owners have come to think it’s fake. One criticizes the placement of the eyes relative to the skull, noting that Leonardo, who was known for dissecting and sketching corpses, would never have made such a mistake. Another blames the conservator for having moved the eyes into the wrong place. Yet another says Christ’s nose is too long. Others still question the rendering of the rock crystal orb he’s holding in his left hand, representing heaven’s crystalline sphere, and why it doesn’t seem to refract the light accurately. More generally, there are many accusations of art world money-laundering, and a whole raft of conspiracies binding the painting to Russia and Trump and in various ways, my favourite of which concludes that it’s in the latter’s penthouse in Trump Tower, hanging, perhaps, beside his fake Renoir.

Nobody draws comparisons between Leonardo’s cosmic orb and the glowing, mysterious, rather beautiful orb that the US President, King Salman of Saudi Arabia and President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt were pictured clasping together in Riyadh recently, although this is a line of inquiry I’d love to lead us all down (but won’t).

Thus passes the glory of the world

Mixed in with all this hysteria are gentler, shared reminiscences of halcyon days studying art history at the University of Washington in the 1980s, when the painting hung for several months in the Henry Art Gallery, and how their professor, “would play Italian music from the period as she passionately made a case that this painting was by the hand of Leonardo. She spoke of the tresses in his hair as influenced by the myriad drawings Leonardo made about water screws and the flow of liquid… I found it all very compelling and bought the poster from the Henry and it’s now somewhere in storage. Or maybe it isn’t?”

And oblique, line-broken recollections,

“I sensed something

something beyond these words perhaps even beyond his other works

in the repainting and distortion

the masterly right hand and restored face still

I was compelled to walk away and walk back

just between you and me.”

Mohammed Bin Salman and Donald Trump inaugurate The Global Center for Combatting Extremist Ideology in Riyadh, 2017

And even balanced voices of reason asking, “Does it really matter where the painting is? Whatever meaning it has is now overshadowed by its role as a conspicuous display of wealth and power. Rather its original purpose, come to think. Sic transit gloria mundi;” which is to say, “Thus passes the glory of the world.”

Nobody mentions that the work, which may have been painted for Louis XII of France, who died in 1515 without a male heir, and may have crossed the Channel to England with Henrietta Maria when she married Charles I, who was beheaded in 1649, marking the end of the English Civil War, and was certainly sold to Dmitry Rybolovlev by Sotheby’s, who he’s currently suing for $380 million on the grounds that they colluded with his dealer to defraud him, might be cursed; but again, this is an angle I’d like to throw into the grand mix.

There are recurring suggestions that the cursed painting’s new owner Mohammed Bin Salman, as a Sunni Muslim Wahhabi – meaning that he should, strictly speaking, consider the artistic depiction of any Islamic prophet a form of sacrilege – may have bought da Vinci’s lost portrait of Christ just to later destroy it in an iconoclastic fury. Others say he may have destroyed it because he’s a nihilistic billionaire in search of new experiences. Or perhaps it’s been bought, or stolen, by somebody else entirely?

What happened to Malaysia Airlines flight 370? Nobody knows

The symbolism hangs here heavy and low; somebody has taken the Saviour of the World away from the world. But then, doesn’t everything that happens feel like a metaphor now? What is this painting, but the whisper of an idea?

Its disappearance has inspired a well-rounded collection of conspiracies that key into many of society’s fears, which is how we tend to react to any news these days. Mysteries, like missing sections of Florentine paintings from 500 years ago, are just blank voids to be painted in with whatever we hope to see there. We’re surrounded by mysteries. What happened to Malaysia Airlines flight 370? Nobody knows. Where’s the world’s most expensive painting? Don’t know. Who painted it? Hard to say.

Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation, 1472-1475

According to my friend Paige, today’s conspiratorial internet manias, which leave reality in shambles, are like a new form of folk art. We’re telling one another stories that make the world seem more enchanting, or terrifying, and repeating them again in more and more twisted forms, and this may well be where the most innovative storytelling is happening these days. In a recent essay published in Harpers, “The Wizard of Q”, novelist Walter Kirn writes about the right-wing Qanon conspiracy and describes how, diving down into it, he realized “he’d discovered a principle of online storytelling that had eluded me all those years ago but now seemed obvious: The audience for internet narratives doesn’t want to read, it wants to write. It doesn’t want answers provided, it wants to search for them. It doesn’t want to sit and be amused, it wants to be sent on a mission. It wants to do.” And so, one night in Arkansas, Kirn and his friend Matthew work themselves up into a euphoric contemplation of Q’s questions. “I sat on the couch. He paced. We thought out loud, competing to crack the message and setting different values for different variables. We argued our cases as the night slid by; we raved away in an ecstasy of guesswork. Q was being good to us. Q was delivering everything we craved.”

a sign pointing to a sign pointing to a sign

What they craved, was a story to chase after. Just like the rest of us, they like to be confused, and enjoy things they don’t understand. We all want to try and understand. We want to believe. We fall in love with mysteries, and things that aren’t there.

The Mona Lisa, which Salvator Mundi was sold as a religious version of, is the most famous painting in the world but only became famous after it vanished, after it was stolen from the Louvre by an Italian handyman in 1911. Right away the gendarmerie had their own suspicions and conspiracies: Pablo Picasso was brought in for questioning, as was Guillaume Apollinaire, though both were released without charges. In the two years before it was found again, more visitors came to stare at the blank space between the Titians and Correggios where it was supposed to be, the four iron hooks from which it had hung, than had ever come to see the smirking painting itself, and often claimed that they could feel it continuing to resonate from beyond. And now we have a similar scenario in Abu Dhabi, where once again a Louvre is missing its da Vinci, which only grows more alluring by its absence.

Louvre Abu Dhabi. Photo: Dean Kissick

Not only is it absent, it may never have quite existed anyway, may just have been conjured up from nothing, from an old copy of the painting it purports to be; a painting that isn’t present in the 16th-Century historical record, has disappeared many times over the intervening centuries, and took six years of research and work to be controversially authenticated and restored. It feels appropriate that it was finally sold at Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Evening Sale, because, whether or not it was ever touched by Leonardo’s hand, it’s a highly Borgesian postmodern endeavour: a da Vinci painted on top of a da Vinci discovered under hundreds of years of dreadful overpainting, which has since disappeared completely. It’s a sign pointing to a sign pointing to a sign, but whatever they once referred to, that’s gone, that’s missing, always hidden round the next corner, out of sight, shrouded in rumours and wild hypotheses, and, like all the great masterpieces, not so much an object as a narrative, a polyphony, told across the ages by thousands of voices. Hopefully one day it will reemerge, and we can go and see it for ourselves, but until that day we’ll just have to listen and read and write and conspire and imagine.