He begins with an improbable concept and follows it through to its logical conclusion, allowing it to become larger and larger and madder and madder, spiraling out of control until it collapses under its own weight and becomes something else. In another episode, he reimagined a dive bar as an experimental performance space in order to flout the smoking ban and invited a couple theater lovers to come along and observe an otherwise ordinary evening of smoking, drinking, and conversation. Afterwards, they tell him this was a powerful work of avant-garde theater, so Nathan decides to hire a troupe of actors to endlessly replay that night in the bar in the kind of obsessive reenactment that seemed more at home in a Tom McCarthy novel than on network television.

The term for this approach to art, as defined by Nicolas Bourriaud in the 1990s, is relational aesthetics: “A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” For instance, Rirkrit Tiravanija emptied out the gallery in his 1990 exhibition pad thai, and cooked Thai food for visitors every day; it was in the relations between everyone that the work was found. In 2017, a couple years after the Nathan For You episode aired, I went to a Tiravanija show at Gavin Brown’s old space in Harlem where he’d made a functioning replica of the bar from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) complete with bartender, complimentary drinks, loud music, and a merry crowd, and you really could smoke indoors, because it was an art installation, and was hidden deep inside this labyrinthine gallery building. It felt like a world apart from the world. Good exhibitions can do this: they can create a version of the world that feels freer, or more enchanting or more vivid, than the real one, allowing you to step outside of your life, and later to step back in with a changed perspective.

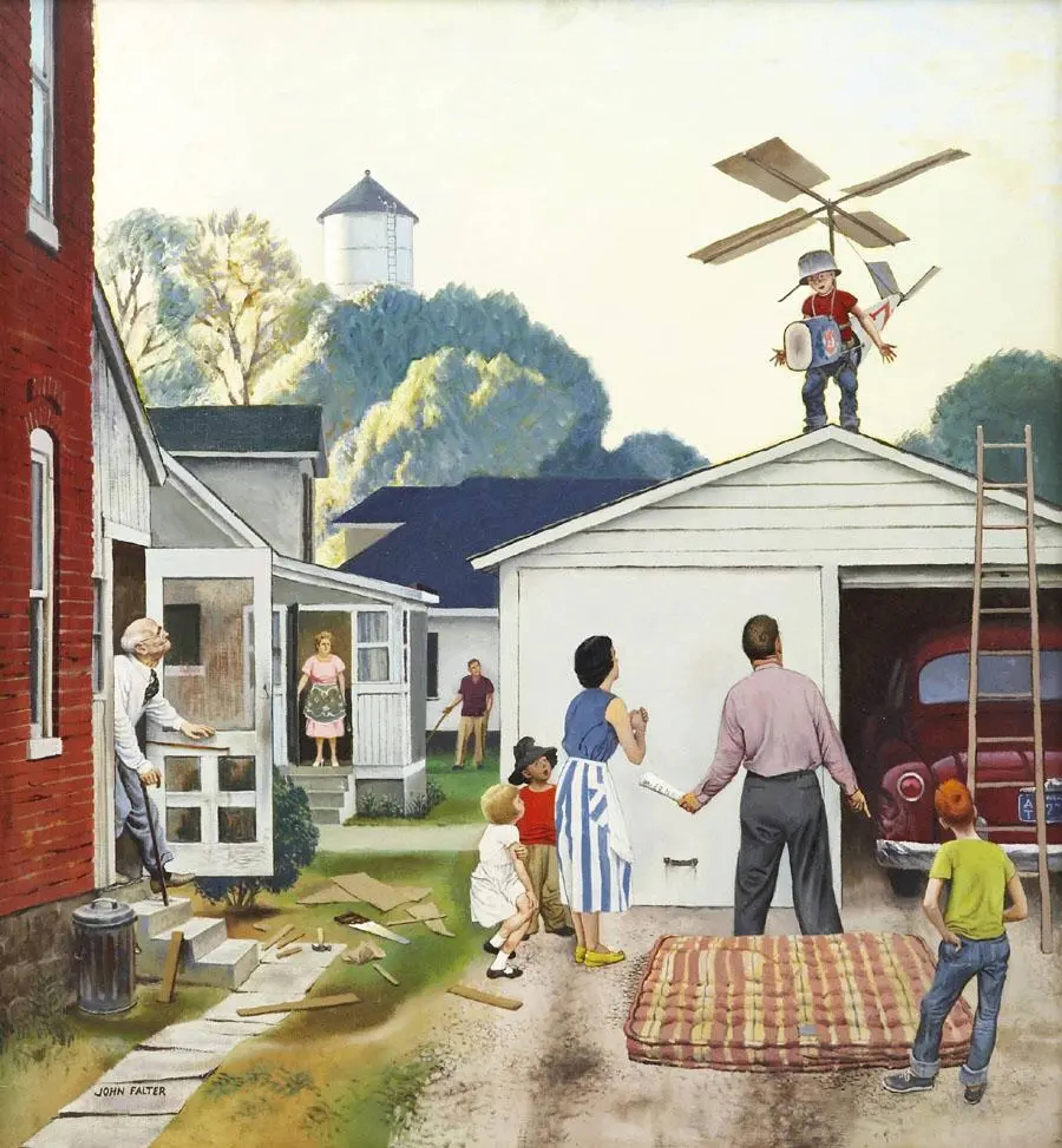

Still from Nathan Fielder, The Rehearsal, 2022

For his new series The Rehearsal, Fielder begins by meticulously remaking a bar, Williamsburg’s Alligator Lounge, in a warehouse so that one of the participants he’s recruited can rehearse for an important conversation he has to have in the real Alligator Lounge. Later, Nathan moves it across the country and reopens it in another warehouse, under a different name, as a friendly place where he can go to get away from the stresses of the imaginary life and the imaginary family he’s created for himself in his show, but not in his real life.

The show’s premise is simple: that you can take charge of your fate and control the pivotal moments of your life if you rehearse them beforehand. Nathan, as is his method, follows his idea all the way through to absurdity, having his subjects followed, and their lives mapped out without them realizing, recreating familiar surroundings for them as elaborate sets, hiring actors to play the people in the centers and the backgrounds of their lives, opening his own unconventional acting school to train actors to populate this world, throwing some real people into the mix too, writing out and rehearsing different dialogue trees, and attempting to prepare for every possible eventuality.

It’s a similar premise to Tom McCarthy’s novel Remainder , which was republished by Vintage in 2007, following a small print run of 750 copies by the French art press Metronome in 2005: a man who has been estranged from and alienated by society, who is suffering a vague posttraumatic disorder, having been knocked out by an object falling from the sky, dedicates the remainder of his life and the generous compensation for the accident to hiring others to reconstruct and reenact half-remembered scenes from his past in the hope that he’ll be able to inhabit the world “authentically” once more. After a while, when this doesn’t have the wished-for effect, he begins to reenact more outlandish and dangerous scenarios. He has a fantasy of total control.

You destroy your life every time you make a choice. The end is built into the beginning.

This desire to inhabit the world more authentically was in the air at the time. The following year, in 2008, Charlie Kaufman’s debut film Synecdoche, New York, to which The Rehearsal has also been often compared, was released. It’s the story of a very depressed theater director whose family has left him, who decides to spend the remainder of his life building and staging a life-size remake of Manhattan inhabited by a large ensemble cast going about their daily lives, and filled with actors playing everyone that matters in his life, in a massive off-Broadway warehouse. He wants to create, for the first time in his life, a formally and emotionally ambitious, powerful work of art so he goes about constructing another version of his life in which he can, if not find happiness exactly, at least stage different paths through life to try to find out where it all went wrong, and whether events might have turned out differently, and how to feel loved. While you do retain some control over your fate, it’s suggested, the decisions you take set you on paths that are hard to get off of. You destroy your life every time you make a choice. The end is built into the beginning. At the end of Synecdoche, he looks back at the skyline of his simulacrum of New York, under the broad, high arch of his warehouse roof, and thinks of everyone’s dreams, in all those apartments, how you’ll never know what they are, or how they’ll turn out.

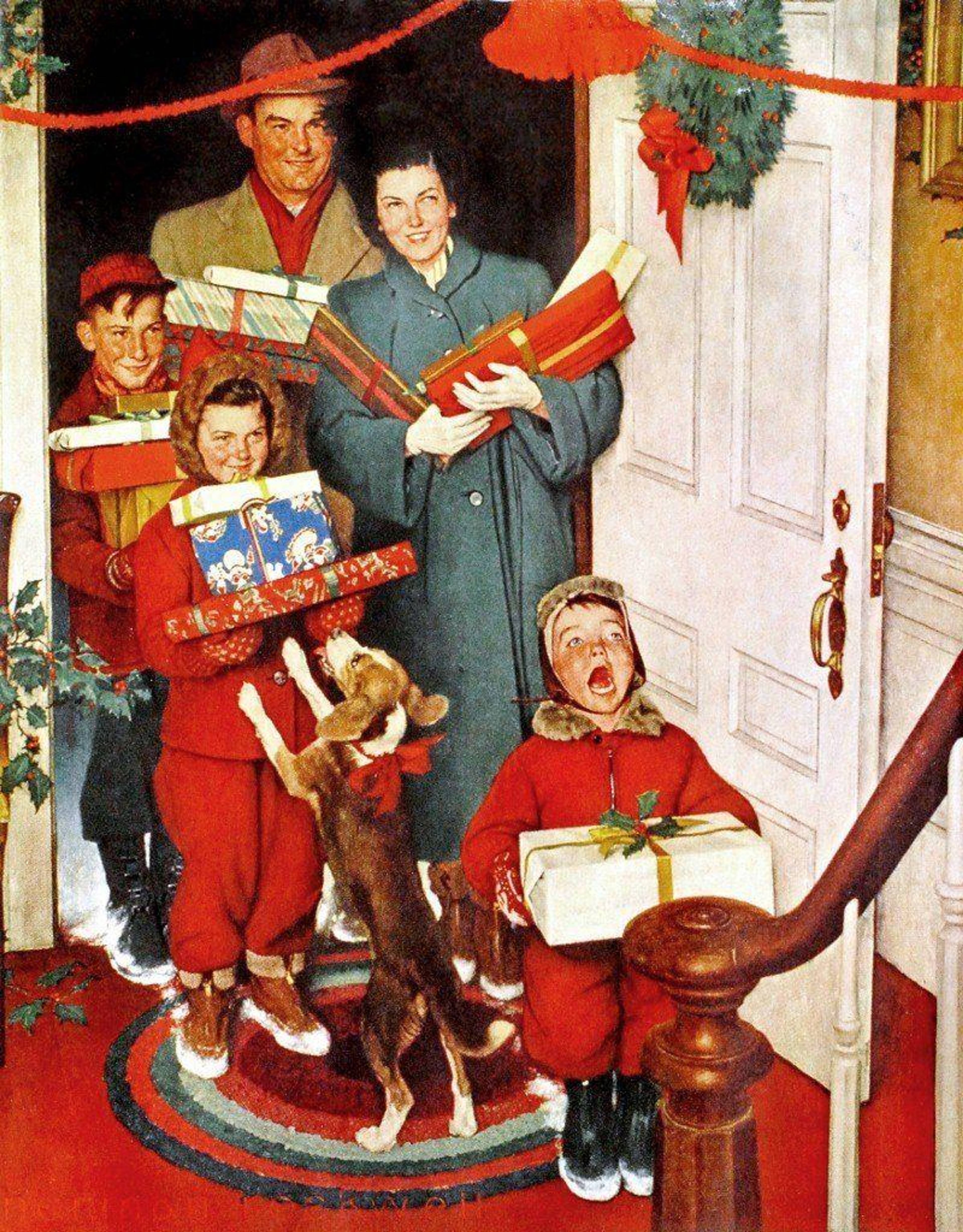

The year the film came out, the world fell into the Great Recession. It was prompted by the collapse of the US mortgage market: by having sold millions of ordinary people mirages of happy lives they could no longer afford. You wanted to have the lives you’d dreamed of and been sold, the nice house that you own, the family that loves you, a warm feeling inside — but the dream was collapsing. The dream was collapsing, and it was out of your hands, it was fate.

Norman Rockwell, Merry Christmas Grandma, We Came in Our New Plymouth, 1951

In her 2008 The New York Review of Books essay “Two Paths for the Novel,” Zadie Smith charted two futures that twenty-first-century literature might go down by pitching two stories against one another: the sentimental lyrical realism of Joseph O’Neill’s much vaunted Great American 9/11 Novel Netherland (2008), which proposed that authentic and moving emotional resonance could be found in the landscape itself, in the colors and lines of clouds above Lower Manhattan, versus McCarthy’s Remainder , which cut harshly violent slashes through reality, like Gordon Matta-Clark chain-sawing conical absences out of abandoned houses, pointing toward a renewal of modernist experimentation.

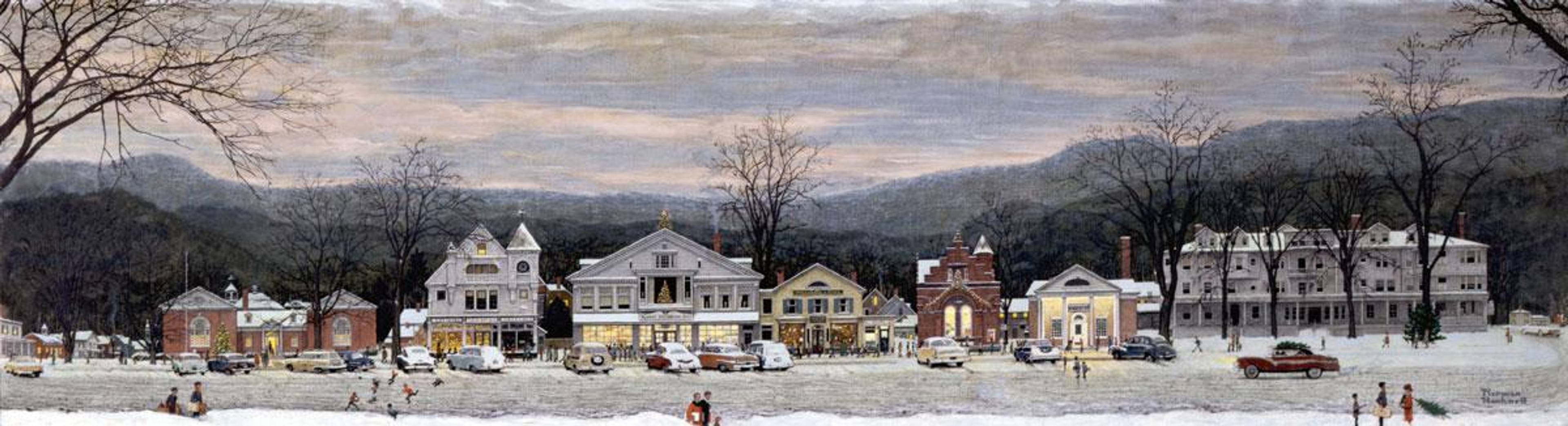

As things played out, of course, literature swerved down a different path completely, turning inward, like everything else, toward self-absorption and humdrum daily life. Autofiction (autobiographical fiction) would be the one path for the novel. It’s a way of remaking: it remakes the author’s life, their interior and exterior worlds, in a more direct manner than before. It’s a remake of yourself. Rather than taking more risks and writing more experimental Remainders, writers have instead adopted a version of the strategy outlined in Remainder: keep retelling your own story, keep recreating what’s already there, in the hope of recovering or making sense of yourself and of what you have lost. After 2008, after the collapse of the dream, writers began to remake their lives as art: there was Karl Ove Knausgård’s six-part epic My Struggle (2009–11), Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, 10:04, and The Topeka School (2011–19), Teju Cole’s Open City (2011) and Tao Lin’s Taipei (2013), Rachel Cusk’s “Outline” trilogy (2014–18), Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) and much else besides. Nathan For You (2013–17).

Across social media, even more ordinary people were also telling stories about themselves. After the collapse of the dream, popular culture was overrun by the performance of happy lives. Even if you could no longer afford the life you’d always wanted, you could still act it out, still craft images of yourself in which it appeared you were doing well. While pop used to offer a fantasy, social media and reality TV offered performances of authenticity; the acting out of fictions that feel real. The game is not to recover authenticity for yourself but to perform it for others. What is lost is the real world, which is sinking below its representations.

Norman Rockwell, Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas, 1967

By the end of The Rehearsal, Nathan is focused on family. He has raised a pretend son, Adam, played by a revolving cast of child and teenage actors, with a pretend partner, Angela, a real person that really does want a family, at an accelerated pace, from birth right up to a difficult adolescence, before going back in time to when Adam was six and raising him again, this time as a single parent, until nine. The finale comes when one of the actors playing Nathan’s son becomes attached to him and begins calling him “Daddy” even when the cameras aren’t rolling, when they’re no longer on set. The boy’s mother explains that he doesn’t have a father at home and can’t, or doesn’t want to, tell the difference between fantasy and reality. He’s having trouble understanding what’s real and what’s not. Well, isn’t everybody?

On Saturday around midnight, I wanted to go to a fashion week party in a Greenwich Village townhouse. It was hosted by Sarah Snyder and some guys I’d never heard of. A crowd was gathering outside, neighbors were watching from their windows, and the security weren’t letting anyone in. Eventually I got a call telling me to go to an ice cream van around the corner, on Washington Square Park, where somebody would be waiting to give us a stamp. The ice cream van had been hired for the night, as a secret way in, but also really was an ice cream van, and really was selling ice cream to passersby that night. You can never be sure of what’s real, and what’s part of some other elaborate production. The guy with the stamp wasn’t there. The ice cream man couldn’t help us. The security guard by the van couldn’t help us. He looked at his phone. After a few minutes, he pulled up an Instagram post and shared it with us: Chicago was eliminating cash bail for second-degree murder, he showed us, and for drug-induced homicide and intimidation and threatening a public official and other offenses. I don’t know how I’m supposed to feel about things. Was this good news or …

Bill Gates was behind this, he said, because he wants to bring the world’s population down. They were getting rid of bail because they wanted Black people to kill each other he said. Bill Gates had a plan for Chicago, and a plan for Africa too. We never did make it into that fashion week party. The ice cream van was only selling two flavors that night: chocolate and vanilla. If you ask for ice cream and they only have two flavors, you know something’s wrong. Conspiracy’s everywhere.

As art and pop have grown closer to life, becoming more literal, more grounded in reality, the popular narratives for making sense of life have grown far more outlandish.

Nathan’s romantic partner in his show, Angela, refuses to celebrate Hallowe’en because she believes it’s a satanic conspiracy, and that satanists are a threat to their family and society. Later, after Nathan performs a Salò -esque shit-eating ritual devised by their imaginary six-year-old son, although they’re really just enjoying some chocolate, she’ll complain that eating excrement is satanic, and her fear of satanism will play a major role in breaking their make-believe family apart. Many think of the world as a conspiracy now. Or a bad dream from which you hope to finally awake. Or a collective hallucination. Or a simulation rendered by your descendants in the future, or a movie, or a made-up cultural scene. As art and pop have grown closer to life, becoming more literal, more grounded in reality, the popular narratives for making sense of life have grown far more outlandish.

Downtown, south of Washington Square Park, autofiction has grown tangled into metafiction, particularly with all the commentary around “Dimes Square,” which is at the same time a micro-neighborhood, an online aesthetic, and an idea, a whisper scattered on the wind, meaning whatever you choose. “Dimes Square,” James Duesterberg just wrote in The Point, “is an object of fascination for outsiders and something for ‘real’ New Yorkers to make fun of; a branded and simulated synecdoche for the city that continues to embody the mix of fear, desire, nihilism, and naïveté of American national fantasy.”

There was recently some controversy around a blog by the writer Mike Crumplar titled “My Own Dimes Square Fascist Humiliation Ritual” and the scene it described: attending the filming of a scene for Peter Vack’s new movie in which a roomful of Downtown and online personalities, hangers-on, and actors, having been asked to act out an internet messageboard in real life, taunted and mocked the author. There was a confrontation over a bad review he had written of Betsey Brown’s film Actors (2021), itself a filmed autofiction about her relationship with her brother (the very same Peter Vack), her father, and her psychologist mother. After the ordeal was over, Crumplar went home and wrote about it, as those who’d invited him would have known he would – and would have wanted him to. When I first read about it, about these people I knew and these actors playing versions of themselves, acting horribly to one another, breaking down in the cinema, I was reminded of Synecdoche, New York (2008) and all its complicated and grandly self-referential metafiction. Hardly anyone appears sure about what was real and what was pretend, what’s theater, what’s reporting, what’s art, what’s not. It seemed to have been a performance that tipped over into distinct stages of unpleasantness, but that might also reveal more of those on camera and who they really are than they would in real life. Sometimes the real person emerges from the pantomime: like in the very odd, unnerving, moving last few lines of The Rehearsal. People want to show you who they are. Perhaps you won’t like what you see.

Still from Nathan Fielder, The Rehearsal, 2022

A couple days after the Humiliation Ritual piece was published, a friend wrote to say, “What the fuck is going on Dean? It’s like the new selfie is a 10,000-word article about what you did last night. The whole city is trapped inside a self-authored Substack. Everyone’s gone through …”

There’s metafiction in the air here. Writing about each other, writing about writers. Everything’s a column about yourself. Everyone’s just telling stories about one another, making movies, staging plays in friends’ houses in the city — plays about scenes that don’t really exist that aren’t really about those scenes that don’t exist anyway — writing blogs, publishing literary magazines and newspapers, hosting galas, hosting talk shows, having readings, running meme accounts, making video games, playing versions of themselves in others’ fictions and their own, and doing so in public. It’s what happens all over the internet already, but with higher artistic pretensions, more Dadaist aspirations, more obscure literary references, more interest from the legacy media and right-wing cultural agitators. We’re all characters in one another’s fictions. I’m a character of Crumps’s. We’ve spoken about it in bars — real bars, not replicas we’ve had built in warehouses. We’re all trapped inside a gargantuan blog that links to other blogs about the blog that make up together a map of the city. I saw this described as the Lolcowification of New York. It’s all mythmaking, lives spun into a story, narcissistic self-obsession as sign of profound soul-sickness in the West. Well, here’s the thing — I do sometimes feel like I’m in somebody else’s play. I do sometimes feel that the world is not real, that it’s slipped below the horizon, below all its representations, that reality is falling away, that nobody’s telling the truth, that it’s all made up. Some days everything feels fake. Everything feels like a bland remake of the past. The art I see is a remake of art that’s already been made so many times before only now it’s worse, and apparently that’s a good thing.

Last year I was invited, to return to an old trope, to what’s called a “sex party.” I have never understood what’s supposed to happen at these soirées because nobody’s ever having sex, at least not until I’ve gone home. That particular night however, seeing the women spank one another, lightly, in the boudoir, and whip one another in their lingerie, taking pictures, making films, as the men sat around among the miniature French fruit tarts and choux buns, and flutes of champagne, I had a distinct feeling that this was all a performance — of course, and what else would it be — but that it was just as flat and lifeless as the paintings in the galleries and auction rooms, and I felt a despair that nobody appeared to know what they were doing, or why, that the painterly avant-garde of Montmartre, the hookers in the Moulin Rouge, that whole dream of modernity, of sauciness, debauchery, excitement, a new world, was all gone, was dead, and yet was still being reenacted. I too had nothing more to offer than a post-Baudelairean ennui with the present and the way we live now, like the Romans by the end of their Empire, in the ruins of our own past.

You are already adrift in a fantasy world of images and imaginary friends and lovers and parasocial relationships (meaning an audience’s psychological relationship with characters performing in mass media). You already live in a pretend world that has been constructed around you, without you even realizing. There is a loneliness crisis in the developed world and a desire crisis as well. They are the crises of the times. You may be dreaming of the life you wished you had, of life being another way than how it is; maybe you don’t even dream of that any longer. Not only are people finding it harder to have meaningful relationships with others, and giving up, but a growing proportion are losing even their desire for and interest in such relationships. This is why Nathan Fielder’s work feels so resonant. The scenarios he conjures are often ways of forcing deeper interactions, more intense personal encounters, twisting staged relationships into real ones, or creating temporary communities. There’s an episode of Nathan For You in which he lures a group of strangers, with the promise of discounted gas, to the top of a mountain, where they camp out together, and bond, and open up to each other. His new show is also about finding unorthodox ways of opening up, and of getting closer to and connecting with others — even if it’s by having them become somebody else, or by becoming somebody else yourself.

Norman Rockwell, Walking to Church, 1952

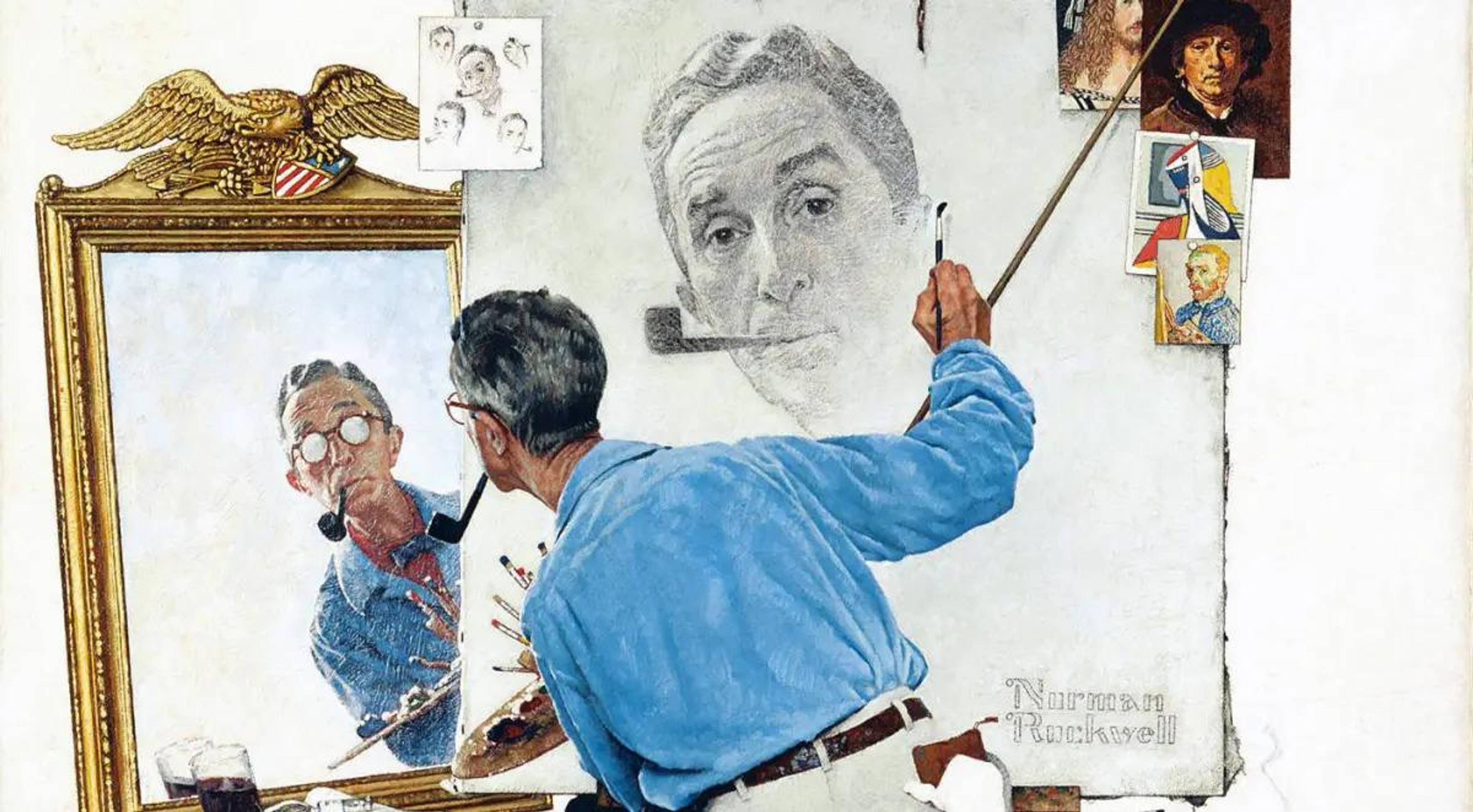

The performance of yourself is the prevailing cultural form right now. Your persona is the message. The most significant cultural development this century has been the erasure of the boundaries between the life that you lead and the way you express yourself: the metamorphosis of life into culture, and culture into life.

Raising his make-believe son on a stage, Nathan turns his life into art. This is not unusual: there is a fully functioning daycare on show in Documenta right now, on the ground floor of the most important venue, the Fridericianum. It was set up by artist and educator Graziela Kunsch and inspired by twentieth-century Hungarian pediatrician Emmi Pikler’s thoughts on early learning. Public Daycare , it’s called.

As everything is already a performance, you might as well push right through into weirder and more involved forms of performance. Fielder hangs out with great artists. But he also goes much further than artists have lately by upping the stakes at every opportunity, making conceptual art on a far grander and more ambitious scale — controlling time and the seasons, the weather, making it snow, commissioning multiple sets, sets of sets, hiring doppelgängers, becoming different people, building a whole world, and worlds within the world, synthesizing reality and fiction many times over — and pushing his ideas to breaking point, crossing the line into the overcast morally ambiguous gloom that art should. Nothing I’ve seen in a gallery this year has come close. It’s the greatest conceptual artwork of 2022.

Fielder makes his life into art like everyone else, but also goes an important step further and makes that art back into life. Rather than distancing himself from the real world by recording it, by walking down the street holding his phone at arm’s length filming everything, he throws himself into his imitation of life as if it’s real. His rehearsals always lead, eventually, back to real life.

You have to leave yourself vulnerable, you have to open yourself up to feeling real pain, if you’re to experience real pleasure and heavy emotions.

Each is painstakingly, delicately staged, with great attention to detail, but usually falls apart regardless. What makes it such engrossing theater is not the staging but the conversations it leads to while it collapses: the chaos that ensues and the emotions that are invoked in performers and audience alike. The Rehearsal has been criticized for exploiting its willing participants, for potentially hurting them, but you have to leave yourself vulnerable, you have to open yourself up to feeling real pain, if you’re to experience real pleasure and heavy emotions. In the final scene, Nathan tells the child actor playing the other child actor playing his imaginary son that it’s “a good thing that you’re sad; sadness shows that you have a heart, that you can feel, that you can love, and you can put your trust in others.” People talk about this online all the time, at least men do, saying they’ll try all manner of terrible things, “just to feel something.” It’s become a meme for sensationless novocaine times. Nathan is trying to become less detached too, he says, to feel more of life as well. In one scene, a graduate of his acting school, playing Angela, the woman he’s pretending to raise a little boy with, turns on him and screams in his face, “Do you want to feel something real?”

He pursues a very traditional dream, of a family and a nice house, in a preposterously overdone, impossible manner. The situation is ridiculous but interesting. At its heart is a straightforward proposition: in this performative age, what if you didn’t perform for money, or attention, but rather for happiness, for a better understanding of yourself and of others, and the things that matter? What if by performing your life, you could experience it more deeply and profoundly? It’s a powerful idea and a form that anyone can try. I have lain on the floor with my girlfriend, after we’d watched an episode, and reenacted an argument we’d had the night before. It was a very unusual experience and I’d recommend it. Next time we should swap roles.

I rehearsed this text myself before too: I wrote about Nathan Fielder for Spike back in spring 2016, before I’d been given this column. I said he was a great conceptual artist of 2015. The opening paragraphs of this piece were lifted from that one. You have only one chance at life. You have to make the most of what you can.

These rehearsals cannot work like they’re supposed to. You cannot control your life, it’s not possible. You can’t control the future, but you can open yourself up to chance and to chaos. Life is better with surprises. Rehearsing, in all of its forms, is a way of preparing. It’s a way of pushing yourself to do the things that scare you, that eat away at you, and to have new experiences. You live in an infinity mirror room of illusions surrounded by pale performances of a dream life that doesn’t really exist and would not bring contentment regardless. Here is a dream of a performance that will lead you back to the real.

Norman Rockwell, Triple Self-Portrait (detail), 1960

___