“In Paris, the Seine had flooded the city, and there were almost no people on the streets. I had the museums to myself, which was surreal. It kept raining. I went underground, where it was busy. I stepped onto a very crowded subway train. In the train compartment I was pressed together with other people. Air and space were forced out of the train compartment. I was infused with the warmth of the other passengers. I smelled unknown combinations of scents. The wet skin. Hair. Being stuck between bodies gave me a feeling of a standstill. In the meantime the train moved very fast. Because there were no doors between the compartments I could see the whole train up to the front. It squirmed like a flexible animal, and I felt like I was in the intestines of this animal. Back in my hotel room, I started to draw.” (Pieter Slagboom, 2020)

I went to a soirée at a millionaire’s TriBeCa penthouse and there wasn’t any hand soap there. The bar was fully stocked, the wine fridge full of chilled bottles, there were pieces by Juliana Huxtable, Aria Dean, Isa Genzken, and Elle Pérez on the walls, a huge vintage da Vinci monograph on the stone coffee table, but no hand soap in the bathroom or kitchen. I was curious. Why get rid of all the soap?

Lists of works and exhibition texts are only available by QR code; the war on the printed word continues.

At Upper East Side and Chelsea galleries, automatic hand sanitizer dispensers guard the entrances. Lists of works and exhibition texts are only available by QR code; the war on the printed word continues. At Gagosian your picture and temperature are taken as well. Some places won’t let you through the door until you’ve filled in a questionnaire on your phone. Have you had the novel coronavirus: yes/no? All of which serves to emphasize the clinical sterility of the evenly lit large white cube, and its separation from the real world outside, the world of death and sickness. Many gallerists are germaphobes. Warhol was also a hygiene freak. New York is returning to the Seventies, they say. At every doorway, a mysterious young lady in a mask takes my name and phone number.

Nowhere else is doing this though. All year in New York, no-one has asked for my details, except for today, when twenty gallery assistants do. The blue-chips are running the only contact-tracing scheme in the country. Down in Chinatown though, artists and critics and dealers are bundling into the new art bar, the secret one, where it’s crowded and open late, and everyone’s drinking inside, like wayward English footballers sneaking off from socially distanced training camp to have sex with Icelandic girls from Snapchat.

Biden palimpsest on Delancey Street.

At Lucien the crowd passes around a picture of Hunter Biden’s penis. Hunter is popular with the Downtown set because he has sex with our friends, lets our friends paint him naked, tells our friends that in his heart he feels like an artist. That’s a difference between the two candidates: one raised an art collector, the other an artist.

We like things we don’t understand. That’s why we like bad painting, and theory, and religion, and conspiratory art-adjacent paganism.

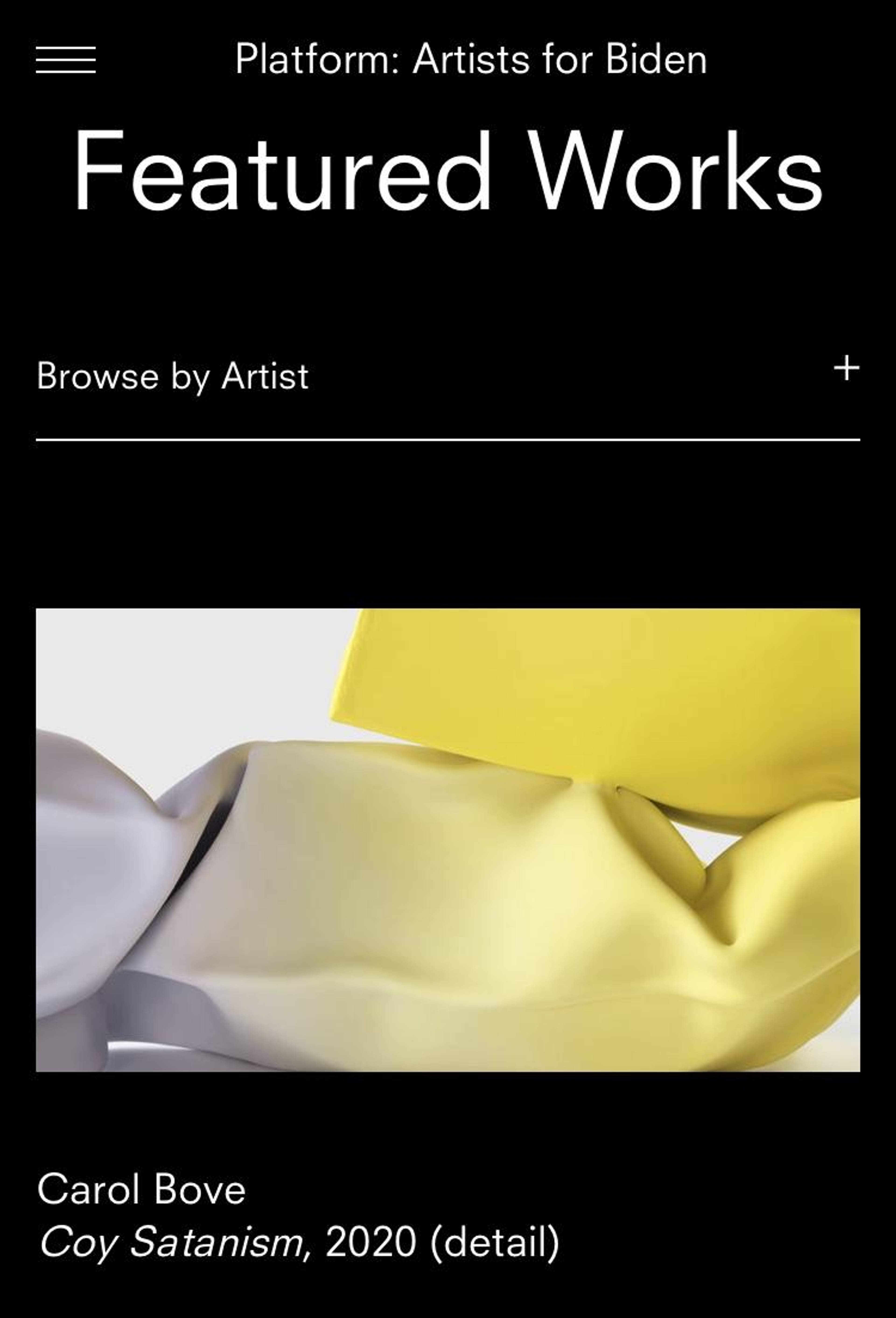

Near the beginning of the pandemic, David Zwirner launched an online platform called Platform on which he hosted lists of available works and prices from smaller, less successful New York galleries (prices have since been removed). It’s like a PDF. Platform was rolled out in Los Angeles, then London, then Paris and Brussels, and has now pivoted into an auction site fundraising for Joe Biden, selling more than a hundred artworks to raise money for his campaign. The first of the “Featured Works” is Carol Bove’s Coy Satanism (2020); there are few things wealthy democrats like more than female artists evoking satanic rituals. This pandemic has thrown artists into unexpected situations. At Zwirner Uptown, Josh Smith paints empty streets. At one of the Chelsea Zwirners, Harold Ancart paints trees. Worldwide Zwirner has laid off fourty employees. He’s opening a new space in New York with all-Black staff. He’s just poached Dana Schutz from Petzel’s roster. He’s always up to something. Nonlinear warfare was inspired , after all, by conceptual art. People like to be confused. We like things we don’t understand. That’s why we like bad painting, and theory, and religion, and conspiratory art-adjacent paganism.

David Zwirner’s Platform: Artists for Biden featuring Carol Bove, Coy Satanism , 2020.

It’s a perfect fall day in Chelsea, blue sunny skies and crisp air. The galleries have reopened, so I’m going to see all of them in one afternoon and find out what’s changed. Has there been a rewilding and a weirding? Everybody’s had half a year to reflect, prepare their shows, and put together something special.

“You’re low on ideas,” says my friend. “That’s why you’re doing this.”

We have a good idea together: shows with an easily apprehended gestalt, like Carmen Herrera at one of the Lissons, or Cindy Sherman at Metro Pictures, can be appreciated through the galleries’ massive glass windows to save time. All this checking in really slows you down; particularly if you’re trying to see as many shows as possible. And while such precautions are understandable, I do think I’ll never do another gallery crawl until the pandemic is over.

We ride Downtown, to Canal Street. On the train my friend tells me it will never be over. Apparently the antibodies don’t work. The vaccine’s going to take years and will only work for two-thirds of us anyway. This is the new abnormal and it will never end. I’ll never be able to go home and see either of my parents without taking on the risk of accidentally killing them; like Oedipus.

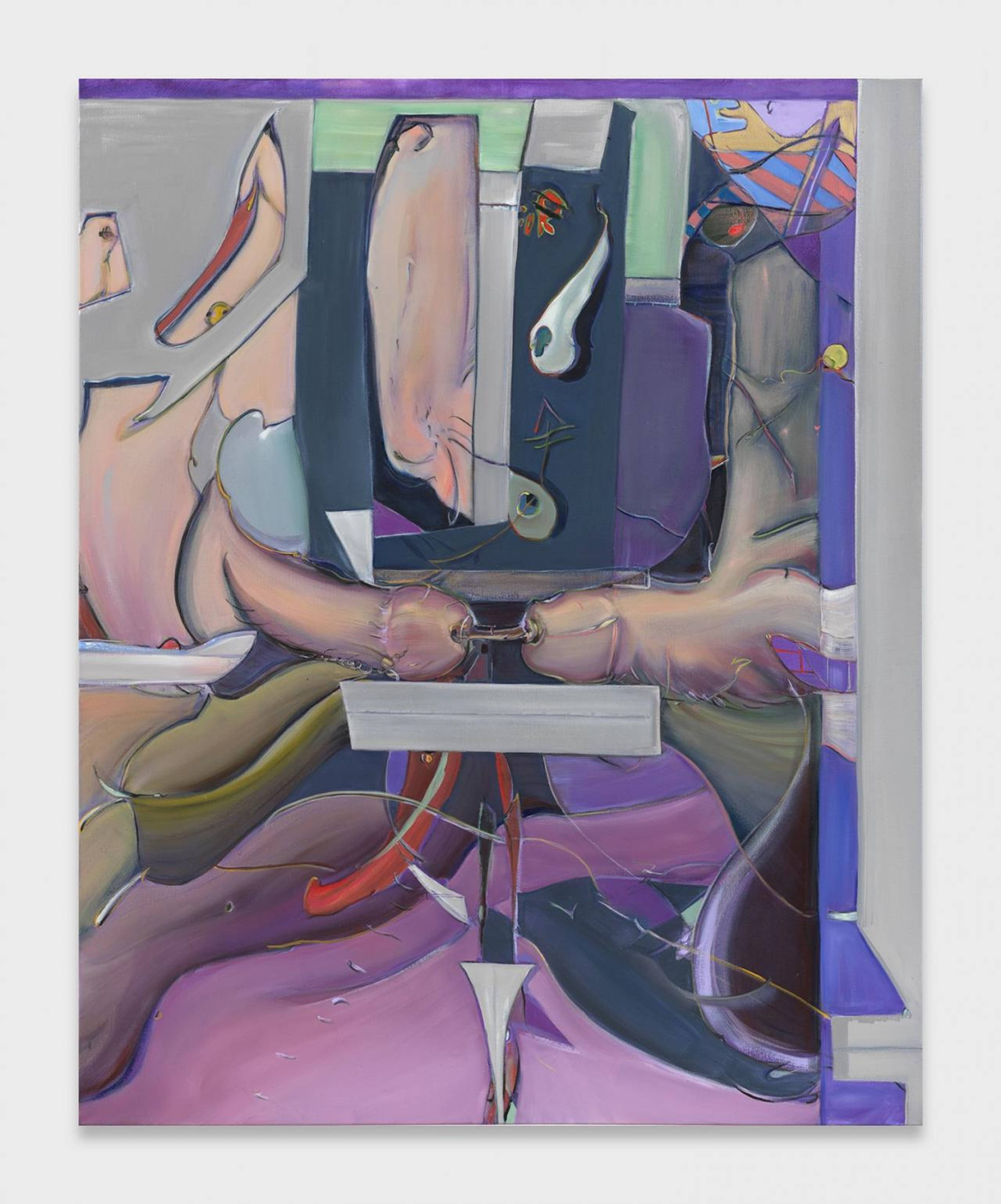

Stefanie Heinze, Soft Becomings , 2020.

How does the body, the figurative painted market body of art from the late 2010s, look now, seven months into the episode? It’s sick, infected, part animal, disassembling. Some Zombie Figuration, at last! Here in these empty white chambers, the disinfected cyborg bodies of art-lovers like us are presented with the perverted, eroticized suffering bodies of artists’ imaginations. At Petzel Uptown, Stefanie Heinze paints mutant, dripping Bellmer-esque forms. Two penises fuck one another in Deleuzean, Guattarian rapture. At Chelsea Petzel, Pieter Schoolwerth paints over collaged stills from The Sims with twisted Francis Bacon faces, layering grotesque expressive masks over unblemished avatars. At Company, Cajsa von Zeipel sculpts oversized polysexual mannequins soaked in come, wearing gloves, sucking on prosthetic nipples. One has a New Museum membership; another a large metal syringe. A sense of mechanical fetish play and bondage recurs across Manhattan. At Matthew Marks, Julia Phillips’s glazed ceramics grab you by the throat, hold you there by the thin pole for your punishment. At Martos, Kayode Ojo shows a chain of handcuffs hanging from a music stand with no sheets. Tal R’s bronze at Anton Kern has no head. Another is only a head. I’ve heard Caroline Calloway doesn’t have knees. At one of the Paces, Julian Schnabel shows recent pieces painted in Montauk, Long Island, on fabric recovered from a fruit market roof in Mexico: gigantic pink canvases with small, tight vaginas. Objects have many lives. There are orifices and phalluses everywhere we go. Art hasn’t changed so much.

Rivane Neuenschwander, Trópicos Malditos, Gozosos e Devotos 08 , 2019.

Rivane Neuenschwander’s exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar, “Tropics: Damned, Orgasmic and Devoted”, is hung with rich tapestries of exotic chimeric beings violently fucking one another. Embroidered vaginas and pools of glowing blood. It’s epiphanic: the sort of show, my friend remarks, a detective might wander into, take a quick turn of, and instantly solve the series of gruesome murders he’s been investigating for years.

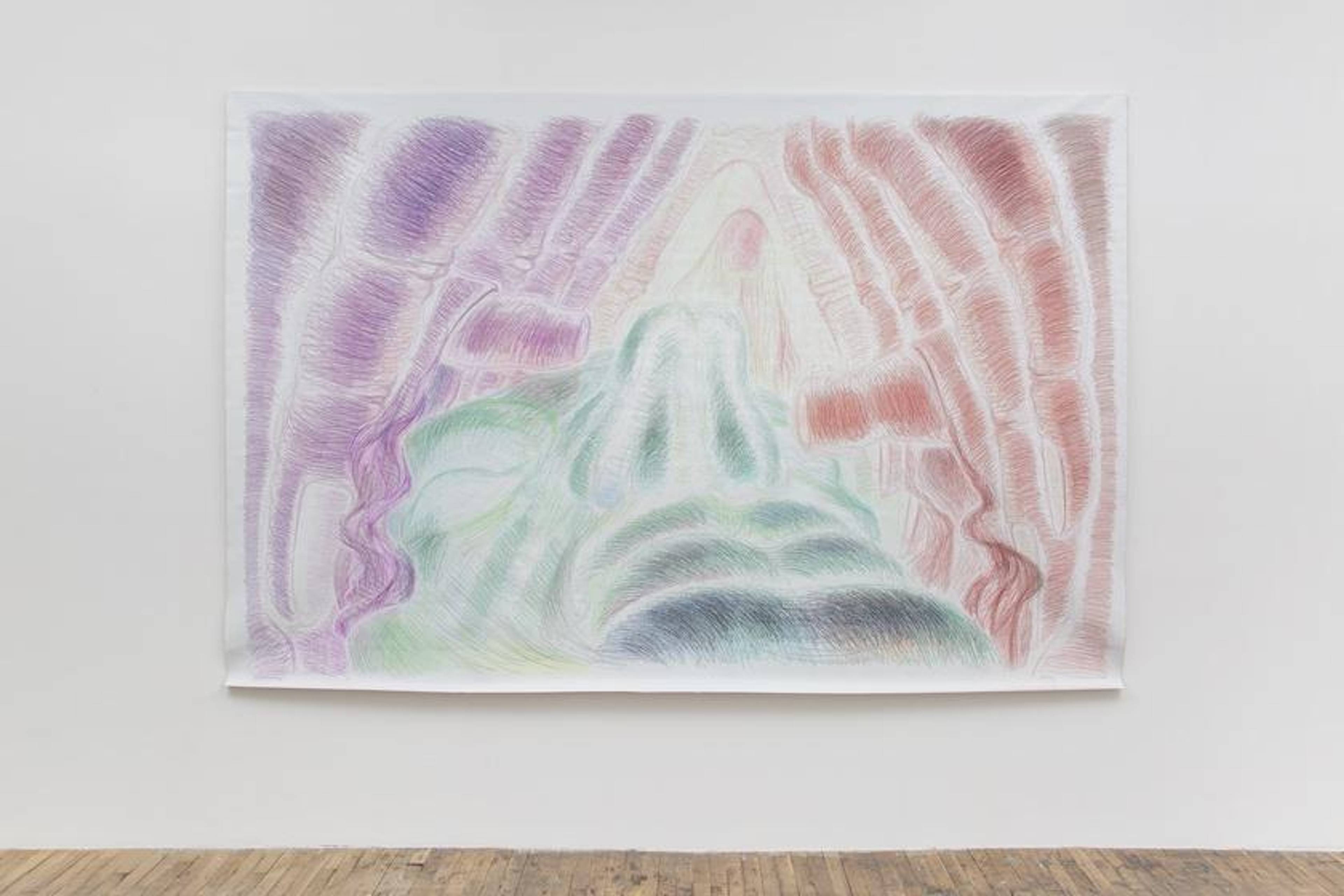

I was told Pieter Slagboom at Bridget Donahue is the best show around. My friend and I agree. It’s full of nerves and presence. The exhibition is a series of giant drawings, made with thousands of coloured pencils, of scenes of degeneracy: Slagboom gangbangs, female-on-male necrophilia, births and engorged clitorises, unorthodox rites of mourning and fertility rendered on the scale of gods. Having wandered through some half-hearted attempts at abjection today, this seems genuinely weird; not perversion for perversion’s sake, not coy satanism, but the sort of pagan esoteric depravity, comments my friend, where you have to stop and look carefully and think about what’s even going on in an image. It’s different. The artist says things like, “I think a person is in fact not one person but multiple people at the same time.”

“How do you feel,” he asks in an interview accompanying the show, which he could not attend, “people will view these images in New York?”

Pieter Slagboom, Fingers , 2020.

In another building, in a different exhibition, we’re looking at a picture of a child in bonnet, drinking a can of Sunkist. All the colours have been reversed. “Has Marxism been unfolded for you? Has [dealer’s name] broken society down for you philosophically?” my companion demands, marching diagonally across the gallery floor at me.

I feel pretty jaded about the art of the last decade, which is why I hardly write about it. After seven months without shows however, I was looking forward to a day out in the galleries, and excited by the prospect of a revival of my love of contemporary art. But no. There is something uniquely deadening about spending a day looking at shows in galleries. It does tend to prompt, my friend notes over reviving Henan noodles afterwards, “weird existential suffering”. Walking the bustling streets of Nolita at dusk though, as the artworks fade to memories, my joy returns to me. The city is opening up to us. There’s life on every corner. I often feel, have done for a long while, about New York, or London, anywhere really, that the city is much more exciting, rife with possibility, than the culture it formally offers. If only I were, and soon I’ll be, better at talking to strangers and following threads.

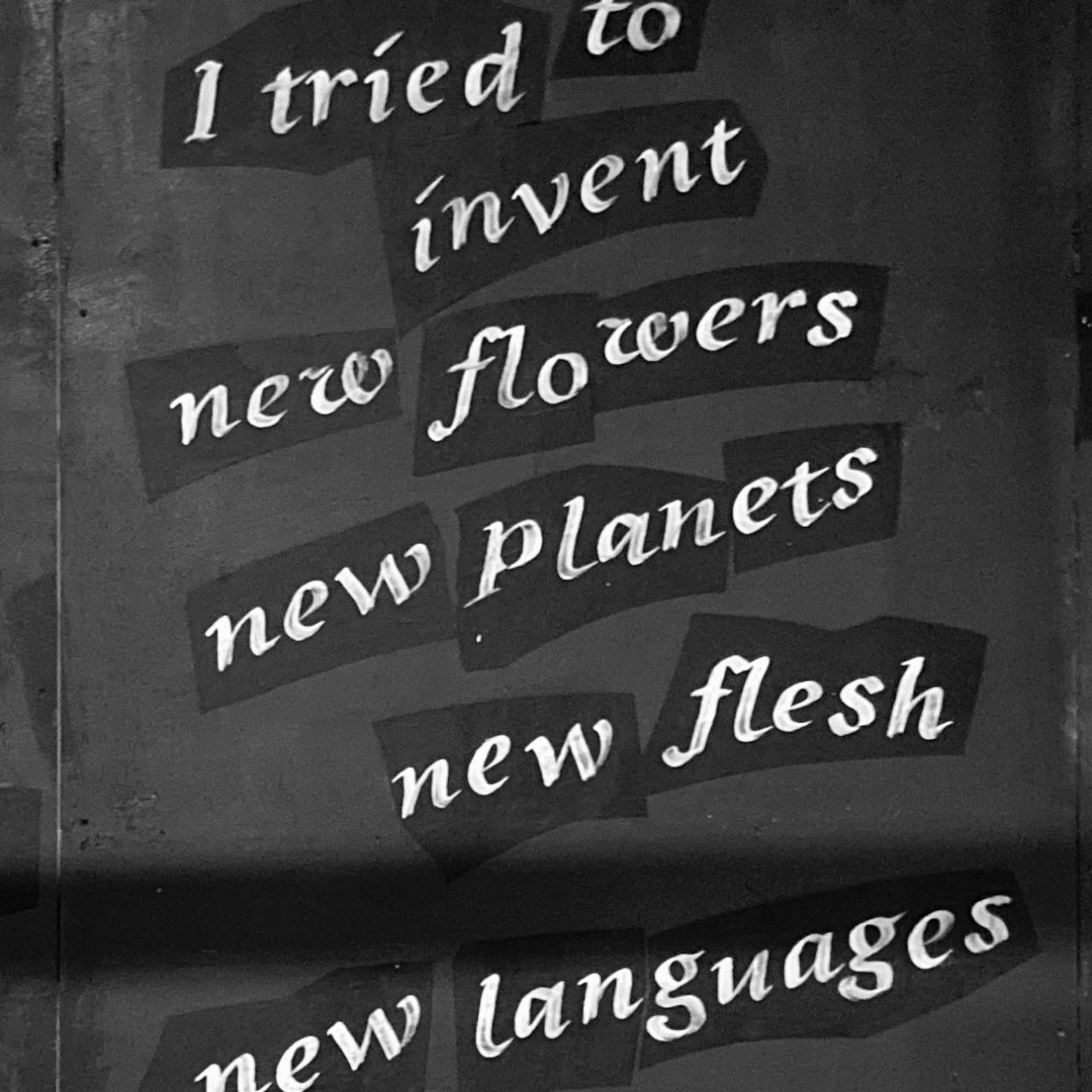

Someone has been painting Rimbaud quotes all over the city. I’ve seen at least a dozen this week:

“I tried to invent new flowers, new planets, new flesh, new languages.”

“A thousand dreams within me softly burn.”

Graffiti, 2020, quoting Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell , 1873.

Amalia Ulman runs a private book club. In the evening, after the galleries, I read some chapters of Alberto Moravia’s Contempt (1954) for her book club, which makes me experience different emotions at once, strikes terror in my heart, brings back horrible memories of past love affairs. At night I read the Bloomberg piece about Japan’s Lost Generation and it makes me miserable, but also lights a fire inside. Why doesn’t art bring up emotions like this? Why does it hollow you out so? Some of the shows we saw are good. But what they are doing, is no longer clear. I don’t feel the way I’m supposed to feel. But how am I supposed to feel? No-one seems to know anymore.

At the other Lisson, Ryan Gander shows sleeping cats and a mouse poking its head out of the wall, delivering a soliloquy about death, the end, and what comes after. “For centuries”, she squeaks, “humans have sedated themselves from this unanswerable worry with addictions to, and the distractions of, drugs, and alcohol, and religion, and money, and technological devices that provide them with information abundance”; to which list must be added art. This painting. This sculpture. This animatronic mouse, does it care for me? Will it comfort me? Where’s the love in the Second Wave? Where’s the death on the wall of this gallery? That’s what makes Slagboom’s cartoons stand out: they’re full of death. They’re pictures of spirits. They’re cycles of sex, birth, and death.

Describing one of his subjects he says, “It’s the dying head of a man with aroused female genitalia of three women surrounding it. So it’s a fantasy or cultural ritual where people die while others are aroused. Or, could dying have been eased if surrounded by sexual arousal? … I gave very many colours to the dead body. We should not be afraid. The death ritual is a way to soften the burden. Everyone lives with burden.”

My friend and I go to a show of photographs. On the way out he turns to me with a sad, exhausted look in his eyes. “I’m so tired of conceptual camera art,” he says.

DEAN KISSICK is Spike’s New York Editor. The Downward Spiral is published online every second Wednesday a month . Last time he wrote about the onset of Fall in NYC.