Dara Jochum: What are you reading at the moment?

Rhea Dillon: I’m attempting to return to Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of the Sable Venus, which was introduced to me by a friend and became a really important book to me. The first half is a collection of poems, and the second half is a kind of rumination through the archive. I think I’ve not even necessarily been desiring to speak directly to archiving, but the archive has been coming to me a lot recently. I’m also reading Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman. Her critical fabulation is about basing the Self in the archive and then fantasizing from there: archival transposition, the elaboration and augmentation of statements, the intensification of silence, the embrace of opacity.

DJ: Does Coste Lewis work the archive into her poems as well?

RD: Yes! Coste Lewis goes through this journey of attempting to find the Self in history, or the Self in an archive, like Hartman. Coste Lewis went on multiple trips to find records of Black women in paintings, in museums, in all these different archives, and she finds that these Black women are often not described in the title of the work at all. Or, if they are, it’s like “slave girl” or “maid.” She pulls together all these different terms of objecthood for black women across a seventy-nine-page long poem. The whole project is about being able to use those titles and work poetry from them. Fragments used to create a whole.

I'm seeking out other people's ideas, other people's myths, that help me explain the experience that I am living in or the experience that I would like to live in.

DJ: You lay emphasis on engaging with writers and theorists in your practice. What’s your relation to these written documents as a visual artist who is also a writer?

RD: Theory in itself is myth. People are constantly building language to understand the frameworks in which we exist, so I see that as just what I am innately doing. I’m seeking out other people's ideas, other people's myths, that help me explain the experience that I am living in or the experience that I would like to live in. I feel that’s where these extensions of language towards fabulation come in: as mythbuiding. Artists are also mythbuilders I believe. Or myth players - a jazz player methodology perhaps.

I’ve always been a reader, I’ve always been a keen observer and these things come from the same place. There is a lot of observation and practice through language and I think if you create and expand time for yourself to think through things there is nothing more powerful for that than poetry and theory. That’s where a lot of my language building comes from and what I care to nurture.

Rhea Dillon, Golgotha, 2020, thread on Barbie blanket mounted on rusted steel cross, 196 x 120 x 30 cm. Photo: Dijby Kebe

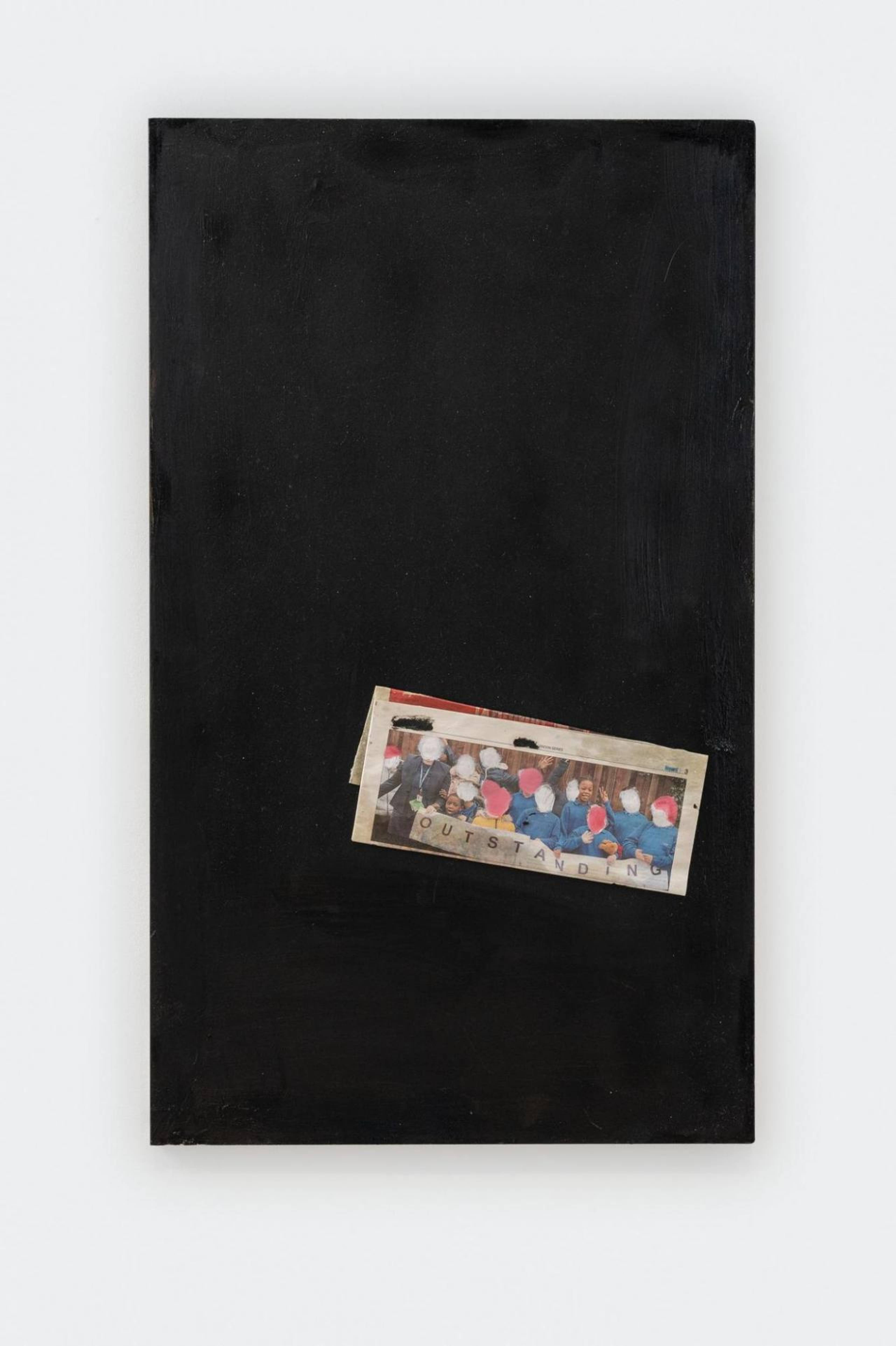

Rhea Dillon, Cellar Door (A Litany), 2020, anti climb paint, oil and newsprint on wood, 86 x 51.5 cm

DJ: Last time we spoke I remember how you were talking about the tellers and the expanders.

RD: Yes, there are the tellers. These people who are changing the course of language or changing the course of basically how we denote time. And then there’s the expanders. There are two sides to it. There is the formulation of my own theory, as a practitioner or a writer, as someone who engages in scholarly text and language. Then there is the reverence and the care for other people who are tellers, they could also be called introducers. As an artist myself, I can expand on those through this really magical place that is the sculptural part of my practice, or olfaction, or painting. I also think that anything can be an “expanding.” Anything and everything is a response.

DJ: But the tellers are still fabulating a kind of myth, right…

RD: Totally! I think we shouldn’t be afraid of the word myth. Myth is also just a form of understanding. If we think about myths and fables, they’re just stories that are used to help people understand something or different avenues of understanding something.

DJ: You’re a multidisciplinary artist, a writer, and a poet. What can the term “poet” include that the term “artist” can’t?

RD: Poet allows for the nonsensical in a way that an “artist” can engage with but doesn’t directly speak to. Essentially, it’s about what I want to change with language. I believe in the nonsensical like I believe in the abstract. I believe in poetics as myth that can soften approach, too. Sometimes a title can also change the approach for a person; it can sharpen or soften it. The simplest line is that I also have a poetry book that exists in the world, so why not just call myself a poet!

A lot of artists are writers even if they don’t directly notate in a linear way. But they all have an incredible capacity for formulating ideas through the lineage that they hold. Whether they hold it on their tongue or in their hands is a different story.

Can I have found a tree? Perhaps not, maybe the tree had to find me. It's greater than me, stronger than me, older than me for sure!

DJ: Your show “The Sombre Majesty (or, on being the pronounced dead)” just closed at Soft Opening. In the show, you map a compendium of found objects lifted from your Black British environment. We see textiles from public buses, cut-crystal glass, a bright-blue plastic barrel, and beautiful mahogany objects. How did these items and materials end up in the show? And how do they speak to one another?

RD: Objects are imbued with the experience of how we live and work with them. I think a lot about the relationships that we build to objects, to materials. How has this wood, this mahogany, affected me or brought me to understand it? How do they also tell a story of my family members? Mahogany is indigenous to West Africa, and it was also found in the materials that were predominantly used to build the slave ships in the first leg of triadic trade. So, it would have been an object that was experienced and used by my ancestors. It’s then a formal, inherited material that I’m working with. A tree for example could have found me, and that’s the same with objects. Objects hold a domesticity. Can I have found a tree? Perhaps not, maybe the tree had to find me. It's greater than me, stronger than me, older than me for sure! So how do I interact with those objects and how have I given a soul to these objects, too?

Rhea Dillon, Both Low Hanging Fruit And The Scavenged High Rise – Either Way: Suspension. So, Slackening The Hold Here I Ask Through The Poethics Of Suspense, “How Can You Rest When Still Strung Up?”, 2022, sapele mahogany crosier, bus seat moquettes and thread, 311 x 110 x 93 cm. Photo: Theo Christelis

View of Rhea Dillon, “The Sombre Majesty (or, on being the pronounced dead),” Soft Opening, London, 2022. Photo: Theo Christelis

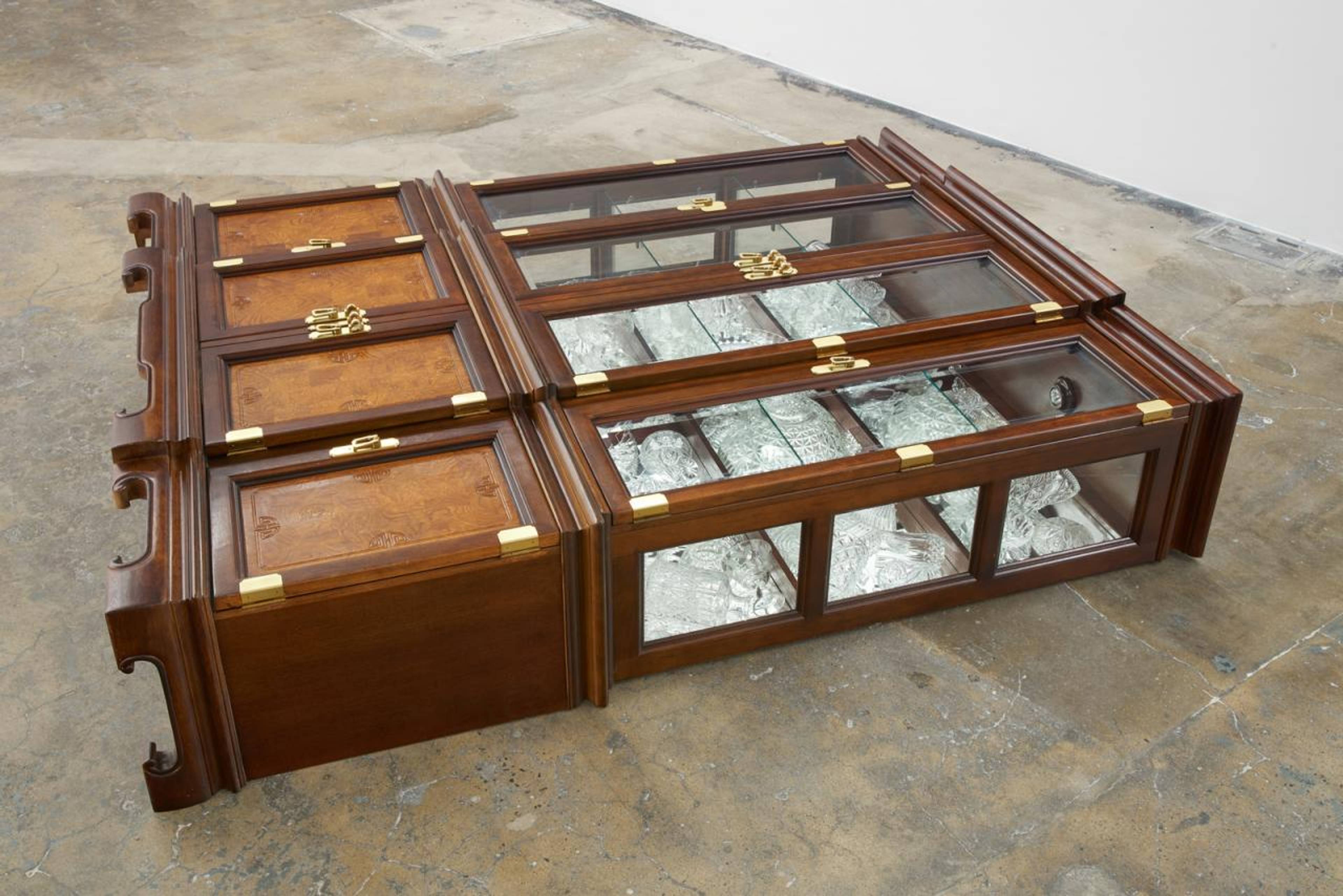

Rhea Dillon, A Caribbean Ossuary (detail), 2022, wooden cabinet and cut crystal, 42 x 208 x 161.5 cm. Photo: Theo Christelis

DJ: Could you talk a bit about the cabinet work?

RD: It’s called A Caribbean Ossuary, an ossuary being a small catacomb or an underground container of bones. That cabinet is the same frame and build as the one that’s in my grandma’s house. It contains cut-crystal glasses and bowls and is placed on its back on the ground, in reference to a kind of mooring. It holds itself in a similar way to a boat, and it is very much an anchoring work in the exhibition, where I am speaking about my Caribbean identity. That piece was created in conversation with my grandma, who was born in Jamaica and is part of the Windrush generation . A cabinet is a symbol and also an anchor in a typical Caribbean household of someone in her generation. There was this viral tweet someone posted “An image that is quintessentially Caribbean” with a photograph of a similar cabinet in their house. So many people were responding, posting their own cabinets, and speaking about what it was like to see them but not be able to really engage with them. The cut crystal pieces were only for when “the queen came to tea.” I took my grandma to see the exhibit on the last day, and we discussed that it’s also a display of class, a “lower-class opulence.”

I collected the cut-crystal pieces in Marseille and shipped them back without packaging support knowing that some of them would break. That was to speak to both the movement of Black bodies, the breakage of some of them, the non-bodying of those bodies, and it speaks to the second part of the show’s title, “or, on being the pronounced dead.” I felt this breakage as a release of souls.

DJ: Do you believe in ghosts?

RD: I believe in souls. And I believe in duppies needing their rest and nurture.

DJ: What is a duppy? What does it look like?

RD: A duppy is a Patois term for a ghost or a soul that could be at a point of unrest or just a point of moving to the next realm. There is a Patois saying, “duppy know who fi frighten.” The literal translation would be a ghost knows whom it can scare or frighten. Generally understood to mean that people know whom they can intimidate. I guess this comes back to fables and myths. But I don’t see them as myths. I see them as truths that use fabling to express what truths are.

Rhea Dillon, Faeces I, 2021, polyester backing and foam, 45 x 55 cm. Photo: Theo Christelis

DJ: This underlying theme of movement, or this state of transit, of the Black body crops up in your work in a lot of different ways — there’s the triangular trade, the movement of souls, and also the Black maintenance workers who use public transport to get from the outskirts of the city to the centre. And you seem to travel a lot to make work, too. Do you feel that this has an impact on how you work?

RD: If I didn’t sit with what impacts me, it would be a disservice to what I experience. I write a lot on public transport. I went to school on scholarship and had to take two buses to get there, the first into the heart of Croydon through this lower-class neighborhood, and then this other bus into South Croydon, which was this threshold into a different class structure. Even the bus was daintier. The bus’s architecture denoted the change of surroundings. I still get the bus pretty much everywhere, I love it. It’s a really languid point of movement. You can’t get there directly but you will eventually. You’re still above ground and can see everything — remaining both physically and consciously aware of your surroundings, unlike the tube or the plane which are very much vortex ways of travelling.

Also, this relates to my idea of trickster methodology which I speak to in my work Every Ginnal is a Star . If you think of life as being a train which is always moving forward, then for a white cis person there is this certain ability to just go through the door into the next carriage, into the next compartment of life. Whereas non-white people always have to employ this trickster energy to find other things that can help them get through to the next carriages. Things that aren’t the key but maybe still fit the lock. They need to go sideways and take detours instead of just going straight ahead, and that takes more time and energy. Just thinking of the cleaning my mum had to do to get me into school, to set me up to be more amorphous and languid, which was my word for 2020. Or my desired word.

DJ: And do you have a word or desired word for 2022?

RD: I’ll choose what first came into my head, but it was two words: Discipline and play. Or discipline in play.

Rhea Dillon, From Landing to arriva(L) In Clear Waters Only I Can Paint Black, 2021, foam, bus seats, nondrying anti-climb paint, plastic, acrylic paint and bleach, 135 x 88 x 72 cm. Photo: Theo Christelis

Rhea Dilon, Nonbody Nonthing No Thing, 2021. Installation view, V.O Curations, London, 2021. Courtesy: the artist and V.O Curations. Photo: Theo Christelis

Rhea Dillon, Dishwater And No Images, 2020. Installation view, Peak Gallery, London, 2022. Courtesy: the artist and Peak Gallery. Photo: Dean Hoy

___

“The Sombre Majesty (or, on being the pronounced dead)”

Soft Opening, London

30 Apr – 11 June 2022