A biographical detail that embarrasses me, but make of it what you will: I went on Birthright, the annual teen tour of Israel bankrolled by the now-deceased Republican casino magnate Sheldon Adelson. The summer after my freshman year of college, sold on the promise of a free vacation, I joined a troop of my college classmates for two weeks of revisionist history and hiking excursions. Over tea in a tent in the Negev or Gold Star beers in Neve Tzedek, Tel Aviv’s gallery district, we mingled with suntanned soldiers, carousing through a calculated display meant to convince young American Jews of our connection to the Holy Land.

The point of Birthright, acknowledged to a more-or-less explicit degree, is to hook up with a member of the Israel Defense Forces. I myself might well have fallen victim to the strange erotic pull of a semiautomatic rifle had it not been for divine intervention. Midway through the trip, I developed an acute case of food poisoning. I barfed on the tour bus. I barfed on the beach, staring out at the glistening Mediterranean. For days, I could not get out of bed. I suspect it was provoked by some stale hummus; the tour guide suspected me of faking it, feigning illness to escape group tourism. I had, admittedly, been acting like a brat, eyerolling at all the forced gaiety. I joked that I was having an allergic reaction to ethnonationalism. Suffice it to say, in my enfeebled state, I did not smooch a sexy soldier.

Denied of this formative opportunity to cultivate ties to a “homeland” that was never really mine to begin with, I failed to come away from Birthright with any meaningful sense of Zionist sentiment. I went home and made a guilt-fueled donation to Jewish Voice for Peace. It’s a miracle that I ever recovered my taste for hummus. But somehow, I managed.

Smash cut to: last weekend, over hummus tahina at one of Berlin’s great many Israeli restaurants, a visiting friend got me up to speed on gossip from her side of the Atlantic. The New York hot girls have lost interest in Urbit, she told me. Another esoteric crypto-adjacent startup has entered the landscape, throwing more secretive parties, subtly shifting the locus of the scene. Its name, familiar to me from murmurs at last year’s Urbit Assembly, is Praxis Society. Its stated aim is to build a new city – a literal city – on the Mediterranean coast, populated by the wayward, the self-starters, and the extremely-online.

Contemporary culture sucks because where we once had virtue, we now have vlogs.

Like many digital-first communities vying to one day graft themselves into IRL space, Praxis currently exists as a Discord server. People exchange gm’s, share reading recommendations, and earn points towards their social credit in the city-to-come by doing wholesome things: expressing gratitude, taking walks, ditching seed oils. Members have coalesced around it in New York and San Francisco, attracted by the prospect of one day living among, per the Society’s official website, “EXCEPTIONAL MEN AND WOMEN SEEKING MORE VITAL LIVES.” The roadmap assures that they have retained a “world renowned architect (to be announced)” to design the city, bankrolled by community members’ crypto wealth and venture capital flowing in from firms like Bedrock and Paradigm.

The next day, a video called EVERY ANGEL IS TERRIFYING, hefty content signified by all-caps title, landed in my feed. From the name, I surmised it might be something like John Akomfrah’s Last Angel of History (1996), which it emphatically was not. Instead, it’s a twenty-minute film sutured together from found footage, narrated by excerpts of a sermon-esque speech given by former VC and self-described “epistemological anarchist” Riva Tez at the last Urbit Assembly. Through clips drawn from influencer workout videos, surveillance cameras, and fight scenes from Hollywood gladiator movies, mainstream culture – or, in their shorthand, “the state” – is indicted for its flaccidity, its failure to produce truth or beauty. The gist of its diagnosis is that contemporary culture sucks because where we once had virtue, we now have vlogs. At one point, the voiceover admonishes: go home, lie in a dark room, listen to Handel, and cry.

Still from EVERY ANGEL IS TERRIFYING, 2023, 19 min.

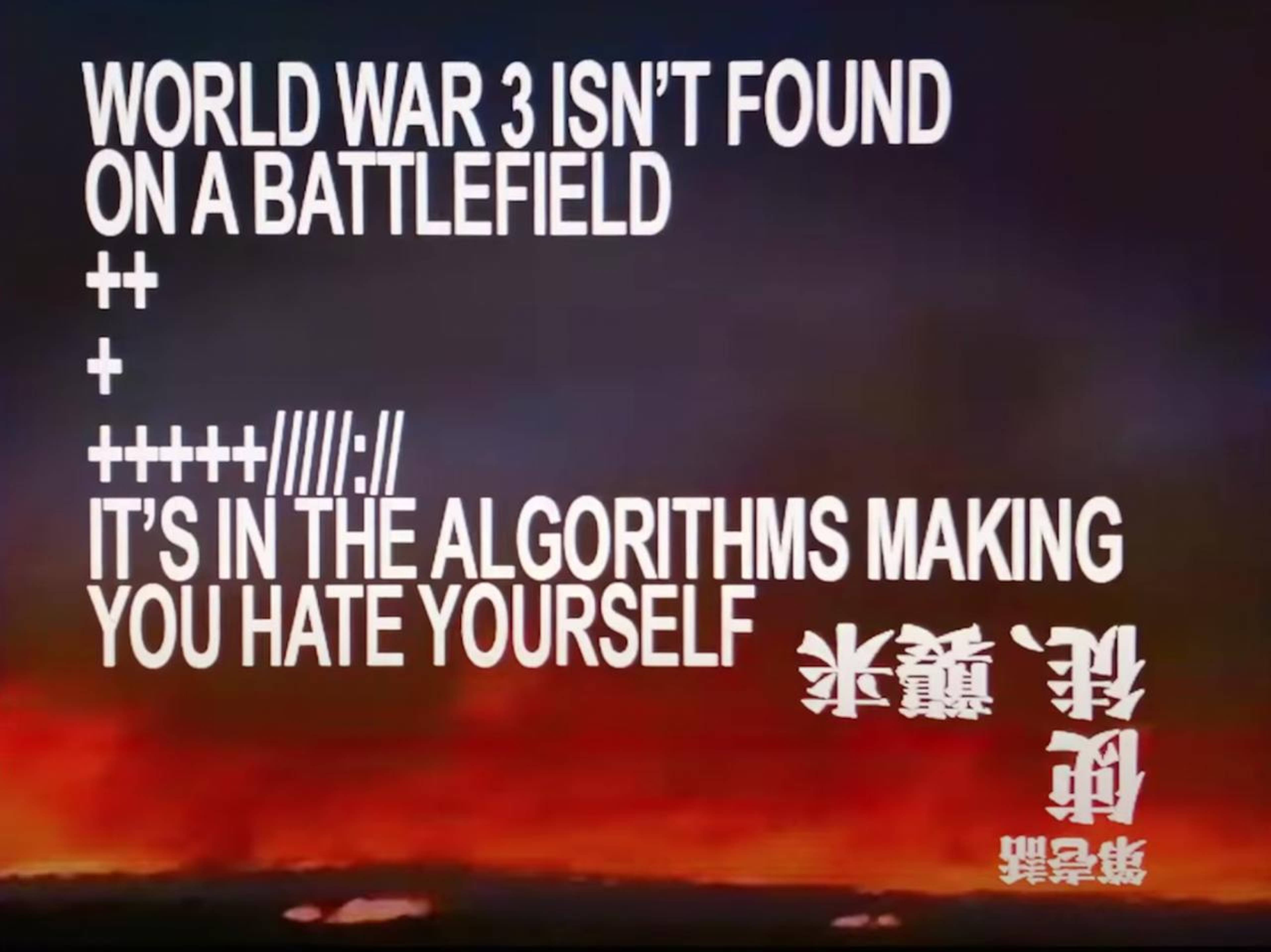

EVERY ANGEL IS TERRIFYING is a propaganda film for a polis in progress, conspicuously set to Adam Curtis music. And to be honest, it’s pretty riling. “WORLD WAR 3 ISN’T FOUND ON A BATTLEFIELD,” reads one intertitle; “IT’S IN THE ALGORITHMS MAKING YOU HATE YOURSELF.” Moments like this one had me nodding along, on first viewing, all “LFG!”. I hate algorithms! I love beauty! But on reflection, they lay bare the film’s fundamental elision: most of the problems it cites, from data-driven attention economies to rampant juvenile ADHD, are fomented by private tech companies as much as, if not more than, by any existing nation-state. That is not a defense of “the state,” but a word of caution: any form that meaningfully improves upon it should probably not be bankrolled by Silicon Valley venture capital.

As a thought experiment, stuff like Praxis – and adjacent notions like Balaji Srinivasan’s Network State thesis, set forth in his 2021 book of that name – have an understandable, if naïve, appeal. The upshot of the Network State, as helpfully glossed in one sentence by “The Network State Quickstart Guide,” is this:

“A network state is a highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states.”

Whoever ghost-wrote that for Balaji makes it sound not so bad. The underlying belief – that most states, as they currently exist, are deeply broken – is not at all off-base. I like a lot of the same things as these Praxis people: daily gratitude, wild parties, listening to classical music and crying. But this is no basis for anything resembling a state – to say nothing of the, ahem, territory issue. I learned as much on Birthright. New states have attempted to establish themselves with justifications that are, historically speaking, much more compelling than the Balaji-ian Network State’s raisons d’etre, crypto-tax-sheltering and regulatory avoidance. To what extent those prior efforts have succeeded depends on whom you ask – but from Israel to Liberland, they’ve sure been contentious, spawning disputes that no amount of VC-backing can resolve.

Still, these ideas are gaining traction in certain spheres online. I saw on Twitter that Balaji just launched his own Network State Podcast. Around the same time, another podcast, The Blockchain Socialist, debuted an excellent series, cohosted with the legal scholar Primavera De Filippi, unpacking the numerous problems with the Network State as Balaji conceives of it. One of the central critiques they raise is that it’s evidently very difficult to secure your claim to land in this world where, already, no one seems to think they have enough of it. Other exit fantasies of the Silicon Valley elite (think space travel and seasteading) have attempted to sidestep the territory issue, but both Praxis and Balaji seem to operate on the principle that it’s merely a matter of “community-building,” acquiring property, and willing a country into existence.

What we need most desperately is to stay with the trouble, to work through it alongside those with whom we are already entangled.

De Filippi also runs through a cascade of further concerns. For one, states built on “exit” over “voice” as their primary mode of governance have no framework for handling internal dissent – which is to say, no bandwidth for the kinds of negotiation and consensus-building where minds can be productively changed. If you don’t like how things are done in the new state, the rhetoric goes, you’re perfectly free to leave and start your own. But wrapped up in the fantasy of frictionless exit – a reality that is, obviously, only available to a fraction of the world’s most wealthy – they dispense with politics as such. This has the unpleasant effect of escalating every conflict to the level of geopolitics – unlikely to result in a patchwork of homies with different views coexisting peacefully side by side.

New collective forms – alternatives to state-based politics as they currently exist – do, though, desperately need to be found. Grappling for one idea in this direction, De Filippi proposes the framework of a “coordi-nation,” an entity that does not seek diplomatic recognition or land but exists alongside or on top of extant nation-states as a non-territorial layer of support. Developing a vocabulary to further articulate these ideas is really urgent – and I just pray that the rest of said vocabulary does not involve any more puns.

One potential antecedent that could help us imagine such new political forms, I think, is the Jewish Labor Bund, a revolutionary social movement of Jews living in the Eastern European diaspora between the turn of the 20th century and the Second World War. I learned about the Bund from Molly Crabapple in the New York Review of Books, in the throes of my post-Birthright disillusionment-slump-cum-identity-crisis. The Bund’s philosophy, though largely forgotten (or obscured) today, was a rejoinder to the settler-colonialism and dispossession that underpinned even the earliest efforts to establish a State of Israel. Crabapple writes:

“The Bund was a sometimes-clandestine political party whose tenets were humane, socialist, secular, and defiantly Jewish. Bundists fought the Tsar, battled pogroms, educated shtetls, and ultimately helped lead the Warsaw Ghetto uprising... Though the Bund celebrated Jews as a nation, they irreconcilably opposed the establishment of Israel as a separate Jewish homeland in Palestine. The diaspora was home, the Bund argued. Jews could never escape their problems by the dispossession of others. Instead, Bundists adhered to the doctrine of do’ikayt or ‘Hereness.’ Jews had the right to live in freedom and dignity wherever it was they stood.”

Still from EVERY ANGEL IS TERRIFYING, 2023, 19 min.

A movement built by working-class Jews whose ability to travel was often restricted beyond the Pale of Settlement, the Bund had no fantasies about “voting with one’s feet.” And crucially, unlike the Network State, the Bund foresaw that as soon as they stake a claim to physical territory, new states are – by necessity – built on land tainted by the blood of others.

Better, then, to think in terms of do’ikayt, hereness: the antithesis of exit. What we need most desperately are different forms of connection and support – new modes of governance, within and beyond the state formations we have now – that can help us to stay with that trouble, to work through it alongside those with whom we are already entangled. It occurs to me that, on account of having written this, I’ll never be invited to any of those legendary parties in the crypto city-state to come. Which, especially if Praxis does get that sliver of coastal land, that secret big-name architect, will probably be legendary. Bacchanalian, even. That’s okay, I guess. I’ve done enough puking into the Mediterranean for one lifetime.

___