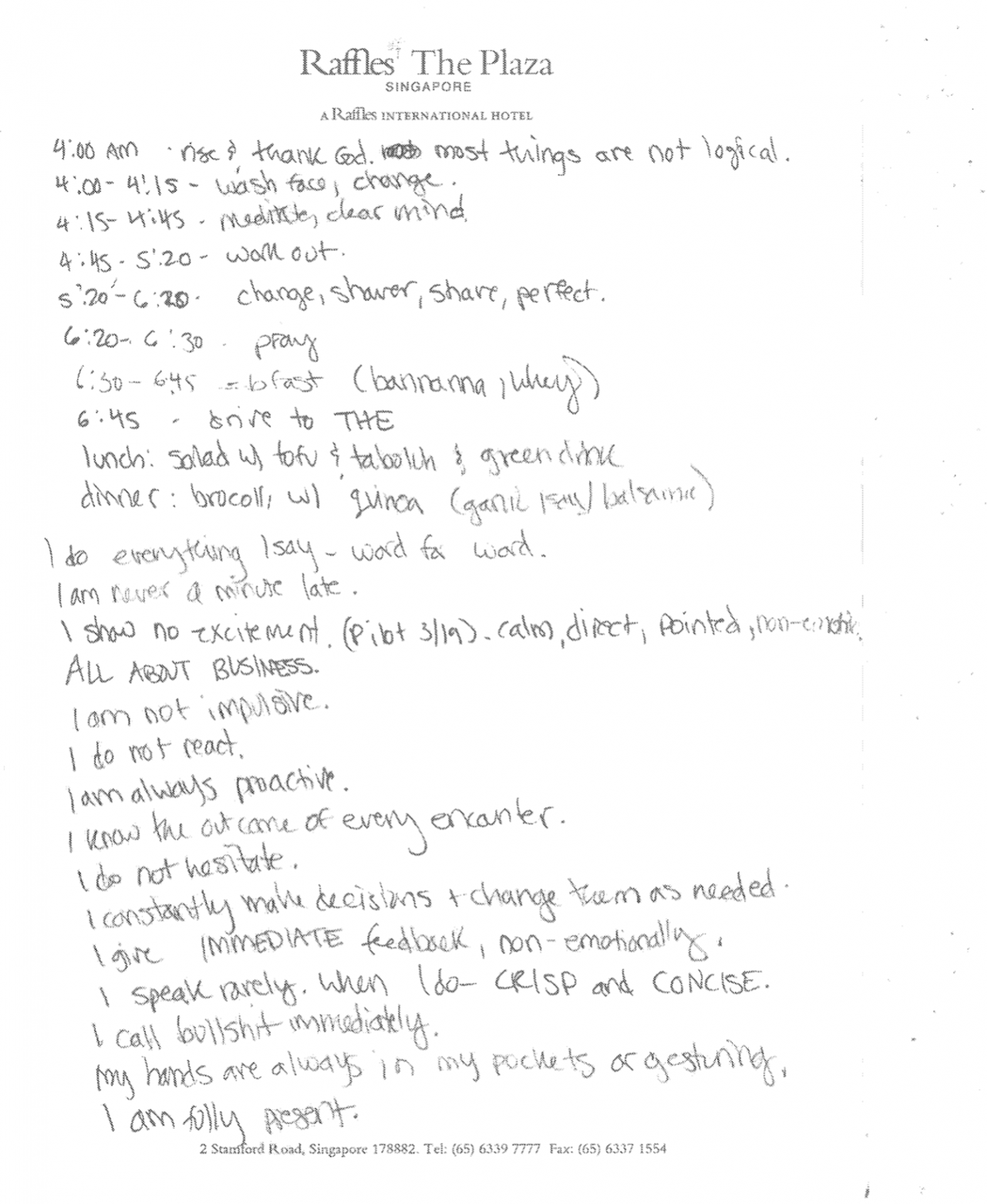

Elizabeth Holmes’ daily routine – handwritten on hotel stationary in surprisingly loose penmanship for someone known for her tight composure – began at 4 a.m. “Rise & thank God. most things are not logical.” Mantras, too: “ALL ABOUT BUSINESS.” “I am fully present.” “I do everything I say, word for word.” “I do not hesitate.” She might as well be That Girl, the aspirational figure of calculated daily comportment, except that her morning practice was transmitted to the public not by some vlog or TikTok, but because it was entered into evidence in her recent court proceedings.

Holmes was sentenced, in late November 2022, to a little over eleven years in prison – convicted for defrauding investors who backed her failed blood testing startup, Theranos. Holmes started the company in 2003. She was nineteen. A number of her Stanford medicine professors told her that her vision, of miniaturized vials and disease diagnosis on-demand, would be impossible to actualize. Steeped in the climate of capitalist motivational sentiment that gripped post-9/11 America – and has gone into hyperdrive since – she took their dismissal as a challenge. And for a while, it seemed like she just might pull it off. In an HBO documentary about the rise and fall of Theranos, a reporter remarks on Holmes’ all-black wardrobe, her efficiency-optimized rows of blazers, likening her to Steve Jobs. Holmes replies, as if insulted by the comparison: “Steve Jobs wore jeans.”

Like Jobs, Holmes sold her vision – or maybe it’s more accurate to say that her vision was sold, in part, by her persona. Unlike him, she ultimately failed to deliver. But by then, real money was involved. Eventually, doctors started asking questions – then the Wall Street Journal started asking questions – then Theranos came crashing down. The US Securities and Exchange Commission filed charges claiming that the company was “an elaborate, years-long fraud” which deceived investors into backing a piece of healthcare technology which simply did not and could not exist. What Theranos had successfully shipped, though, was a certain paradigm of subjectivity – the archetype of a founder; a case-study into what happens when the affirmation of entrepreneurial grit gets out of control and goes wrong.

Exhibit 7731: handwritten account of Elizabeth Holmes's daily routine and affirmations

The problem with venture-funded startups, my friend who works in FinTech tells me, is that there’s not really an off-ramp. No recourse for failure. Which strikes often, if not always as spectacularly as with Theranos. VC-backing trades in charm, charisma; founders are rewarded for salesmanship, if not always social responsibility – or skill at running a company. If things go south, he explains, there’s basically no choice but to desperately pivot, recombining the pieces until eventually either striking gold or petering out.

Has someone who uses “perfect” as a verb on her self-imposed daily schedule ever been known to quietly accept defeat? Criminal intent notwithstanding, there’s something, like, libidinally compelling about Holmes’ resolve. I remember, reading about the trial, that Ayn Rand parked her discourse of moral virtue – which for her, too, was bound up with achievement – in the character of an enterprising young woman. Dagny Taggart, in the novel Atlas Shrugged (1957), is said to have started her life “with a single absolute: that the world was mine to shape in the image of my highest values and never to be given up to a lesser standard, no matter how long or hard the struggle.”

Taggart, and indeed Rand, is the spiritual forebear of a pervasive grindset embodied in Silicon Valley and beyond. The software dev and critic Wendy Liu diagnoses it as “the fable of the invisible hand” – the expectation that enterprising individuals in a free market are the most efficient, creative, and morally-justified drivers of not only innovation but positive social change. A behavioral economist quoted in the Holmes doc suggests that society needs her slightly delusional flavor of ambition: “Without it, we wouldn’t have startups!”

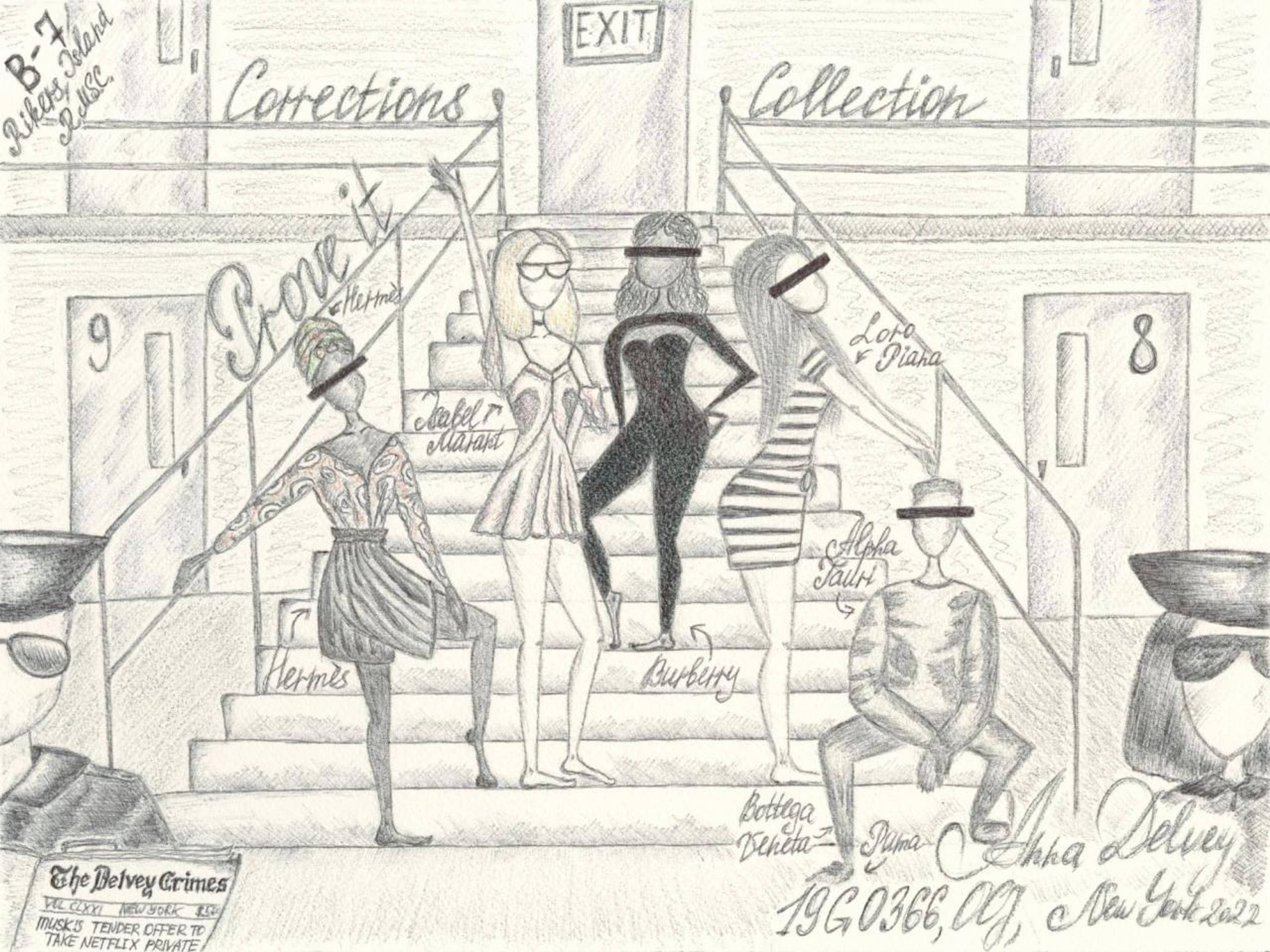

Such a mentality penetrates well outside the boardroom, as evidenced by a new crop of photos of Anna Delvey – the exemplary entrepreneur of the self, a house-arrest ankle monitor resting above her Manolo stilettos. She was styled and shot for The Cut, the publication that first broke her story: impersonating a German heiress and charming her way into a few hundred thousand’s worth of upscale goods and services. Recently released from Rikers, Delvey – legally, Anna Sorokin – is now under house arrest, appealing the threat of deportation. Delvey appears, gleaming under fluorescent subway lighting, en route to a weekly meeting with her parole officer, clad in all-black, head to toe Luar. The hero shot has her leaned up against a vintage car with California plates, like Joan Didion famously perched on that Stingray in the southwestern sun.

Anna Delvey, Corrections Collection 2022, corrections facility pen and pencil on smuggled watercolor paper. For sale via Founders Art Club

Like Didion, Delvey was, in some ways, a chronicler of the mythologies of her age – except, rather than reporting on them, she embodied them, metabolizing them through an impressively durational performance. The writing of the self; a motivated gesture of lived autofiction. A poster in her home reads: “New York women have their nose to the grindstone and ears to the underground.” Questioned about whether she stands by the philosophy that got her into all this legal trouble, Delvey offers: “It’s all about presenting who you are. It’s all about the pitch.”

Big headlines, this month, dominated by girls on the grift. Women doing white-collar? Anyway, I keep sitting down to watch Billions but getting distracted, interrupted by reality. Crypto went bonkers with the fall of FTX, a major cryptocurrency exchange that collapsed into bankruptcy due to hilarious, gross mismanagement. The broader contours of the story are, dare I say, arresting. But Sam Bankman-Fried – AKA SBF, the company’s erstwhile leader – is not at issue in this column. A salient dimension of the many-sided scandal is that FTX might have used its customers’ money to prop up a trading firm called Alameda Research. Its twenty-eight—year-old CEO, Caroline Ellison, is the one of interest here.

I learn from one of those celebrity info sites made from web-scraping bots that Caroline – in the Twitter discourse, she’s never “Ellison,” only “Caroline” – is a Virgo and that her net worth is $222.4 million, though I’m no longer sure about that second point. Caroline, like Elizabeth Holmes, went to Stanford. She is described in New York Magazine as someone with “a philosophical aversion to risk management.” Caroline and SBF lived together in a mansion in the Bahamas. So did some friends, who were also their employees, and were rumored, in classic Rationalist fashion, to also be a polycule. With them lived an in-house performance coach, who was also their in-house psychiatrist. Judging from the lack of professional ethics this doctor displayed by going on the record to discuss his clients’ mental health in the New York Times, he likely had no problem prescribing the copious amounts of stimulants that everyone there was allegedly on.

A Milady NFT allegedly owned by, and at least superficially resembling, Caroline Ellison

Caroline’s profile treatment in New York Magazine was a world away from the Delvey hagiography. Caroline is not photographed for the article, or any recent article, presumably because she is in hiding. No one offered to dress her in Luar. “When it was revealed that Alameda had used funds from FTX customers to cover its losses from risky trades, Ellison, ‘her voice shaking,’ told employees in a meeting that she had known about the money transfers between the two companies,” the profile states. Its headline weighs whether Caroline was the firm’s fall girl or the architect of its relentless, risky strategy – a victim or a mastermind, NPC or Main Character.

When FTX first went bust, a Tumblr account called “worldoptimization” was making the rounds. It’s said to be Caroline’s, and was tied to her Twitter. Its name comes from Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality (2010), an elaborate fanfic by Eliezer Yudkowsky, the founder of LessWrong, a prominent Rationalist blog. The Tumblr, now deleted, has resurfaced in screenshots and piecemeal archives, mined – not least, I’d imagine, by embittered users who lost money of their own in the tanked exchange – for insight into the mind that did them wrong. What does worldoptimization tell us about herself? She’s a “deconverted trad” and a self-identified “8/10 degenerate.” Above it all, she tells us, she likes to see a woman in power: “Honestly this is so uncool but I love it when fiction has representation of literal girlbosses, like women managing people and running stuff. I’m like omg it me.”

What happens when you delusionally manifest-slash-force-meme yourself into becoming That Girl so hard that the feds get all up in your business?

Reality is replete, right now, with “literal girlbosses” spinning elaborate fictions. Fumbling the lines between reality and artifice, managing people and running stuff, running stuff into the ground, running away from the law. These are, at least in part, cautionary tales of individual irresponsibility – but they’re also, more profoundly, indictments of a wider cultural pathology. These women are probably criminals, but are also, in a sense, victims: of an obsessional fixation on achievement; of a culture that centers personal ambition over collective flourishing; of a myth of How To Make It In America. Of second-wave feminist sentiment – workplace success as the locus of women’s lib – stripped of its intended meaning. Of the pressures of startup-ification and venture-capitalization creeping into subjectivity; of the absence of a viable off-ramp. The stories they’ve told about themselves, and these stories’ material impacts on the world, feel realer than the avenues for escaping them, if such avenues exist at all. What happens when you delusionally manifest-slash-force-meme yourself into becoming That Girl so hard that the feds get all up in your business? What do you do then? Pivot!? Die?

Lying, I learned from Atlas Shrugged, has a reality-warping effect. “A lie is an act of self-abdication,” Rand writes, “because one surrenders one’s reality to the person to whom one lies, making that person one’s master, condemning oneself from then on to faking the sort of reality that person’s view requires to be faked.” It’s a vicious cycle; a feedback loop accelerated by the kind of chronic over-promising paradoxically encouraged by the Randian dogma of personal achievement.

When you lie, you become responsible for managing other peoples’ realities – you take them on as stakeholders in a shared fiction. And how do you maintain shareholder confidence when you know the ‘biz is doomed? Optics. Doubling down. Being the boss and selling it, because nothing else is saleable. Selling the fuck out of it, like Anna Delvey sells prints of the art she made in prison. Affirming to yourself that you do not react, you are always proactive, you call bullshit immediately. You are fully present. Like Holmes, described by Henry Kissinger: “You have to remember, she has a sort of ethereal quality. She is like a member of a monastic order.” Or Delvey, forever in my inner monologue: “It’s all about presenting who you are. It’s all about the pitch.”

___