Some people like to imagine the Internet as a series of tubes. Certain others of a more esoteric persuasion believe it’s made of demons – citing, as evidence, how the www in a web URL corresponds, in Kabbalistic numerology, to 666. The French philosopher Michel Serres likens digital networking infrastructure to angels, messengers “in service of the Word” that recede from visibility as they relay their transmissions. The truth is that the internet, the material internet, surrounds us, above and below: satellites and subsea cables encircling and penetrating the planet. It is everywhere, plainly there but rarely visible, revealing itself only ever in partial glimpses: the protrusion of a wire or the ping of a notification.

Such glimpses populate Nile Koetting’s “Unattended Access,” a show at Paris’s Parliament Gallery filled with miniature sculptures of monitors, display machines, and theaters – all visibly plugged into hard drives and power sockets, their cables lying prone to visitors’ inspection. The Japanese-born, Berlin-based artist has turned the gallery – a hip outfit in Paris’s 11th district – into a playground of diminutive 3D-printed objects, including various little venues, or apparatuses, of spectatorship: movie theaters, dressing rooms, and diagrams of seating arrangements, powered by DIY computers with infrastructure laid bare in plain sight.

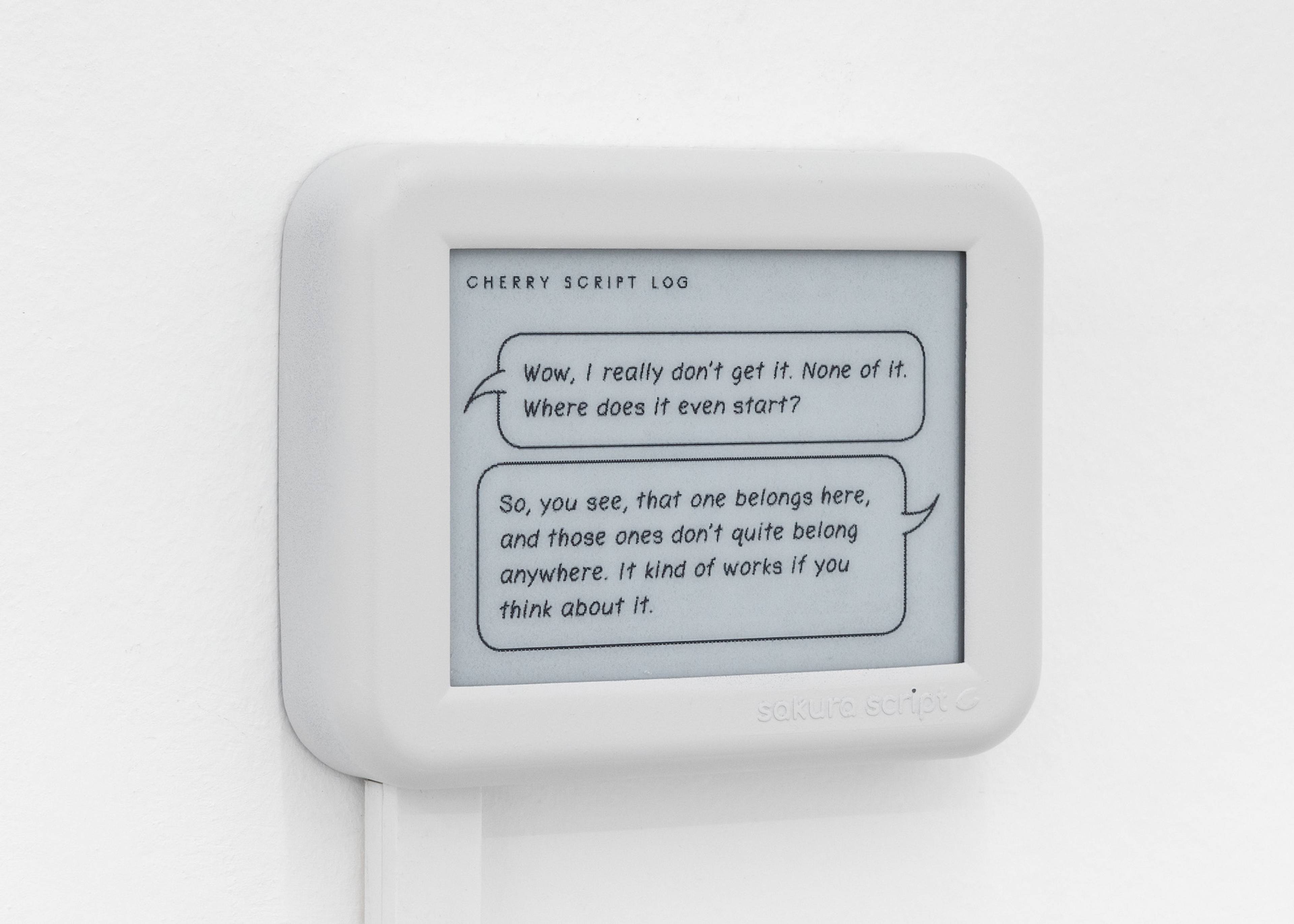

Nile Koetting, Cherry script, 2023, e ink display animation, 9.5 x 12 x 2 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Parliament, Paris

Many of these beguiling sculptures meld theatrical spaces with the visual vernacular of tech startups. For instance: Dream cinema lo (2023), a miniaturized rendition of a real theater in Japan, where rows of beds stand facing the silver screen. I half-expected to see some tiny being tucked into Koetting’s model, reclining on a mattress the size of a Tictac box for a night at the movies. On the small screen, there’s a video of animated builders at a 3D construction site, laboring over a massive Mac monitor. These figures, whose animation style calls to mind the ubiquitous “corporate Memphis” of millennial advertising, are the only humans to appear in Koetting’s show. Nevertheless, the sound of ambient, faraway footsteps filters into the gallery from speakers installed in each corner – the noises of a distant, invisible audience punctuated by the occasional ping of a notification or a computer’s boot-up jingle.

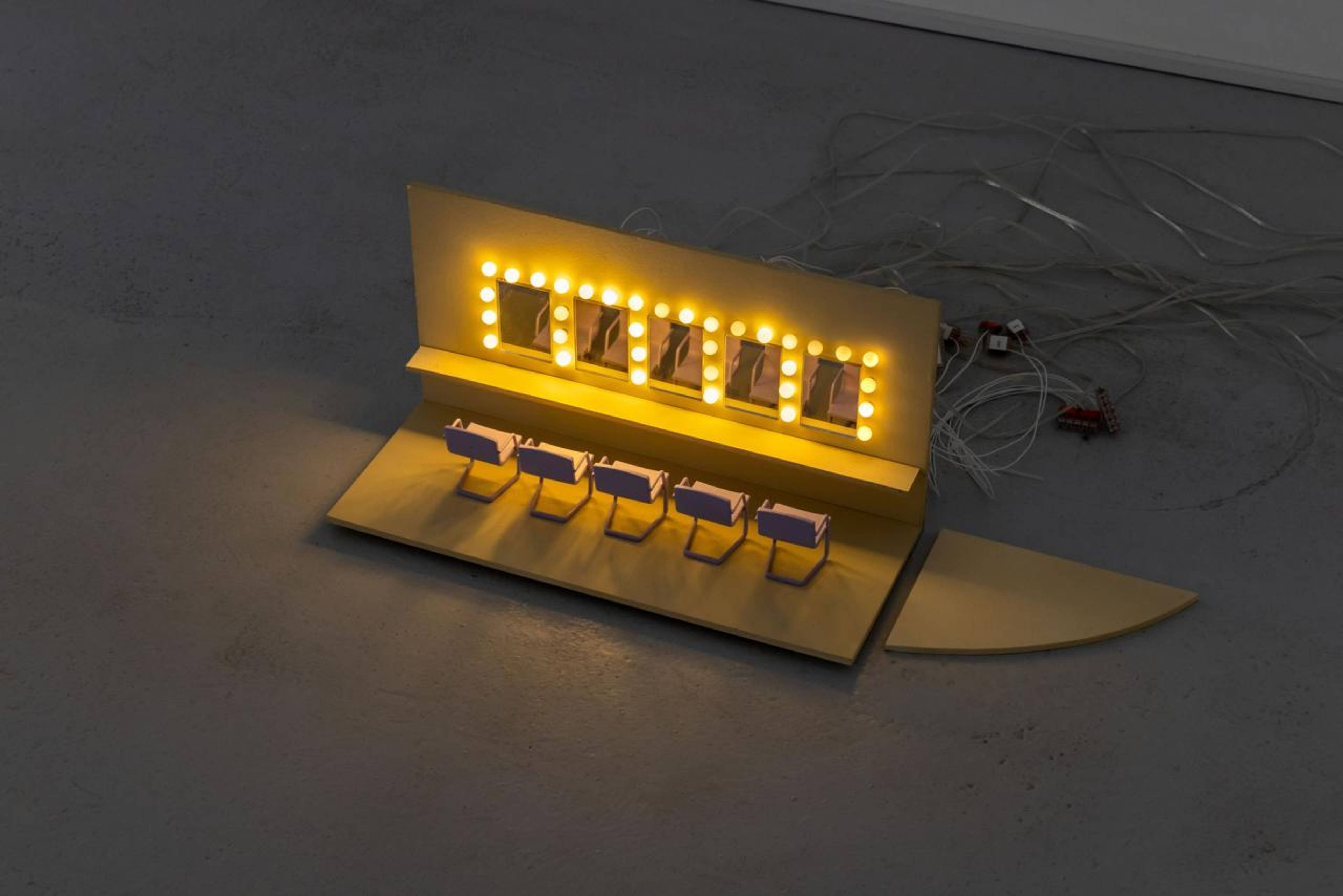

Nile Koetting, Make up room, 2023, mixed media installation, 19 x 37 x 15 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Parliament

Elsewhere, we find human speech, hauntedly disembodied. Take a pair of Kindle-sized display monitors, the Cherry script works (both 2023), wall-mounted screens installed, like most of the show, well below waist-height. Each replays a “script” of lines that Koetting wrote or found, riffing on the kinds of chatter native to art and business. One features an imagined exchange, carried out in floating speech-bubbles, between two visitors to an exhibition that, based on their description, sounds a lot like this one – mise en abyme! On the other, a series of text-messages and office software graphs share advice geared at “optimizing” an artist’s studio practice: real insights gleaned from a consultant that Koetting actually hired. Its punch line is a line-graph, created in a real corporate modeling program called Vensim. If Koetting diligently follows the advice herein, it promises a healthy uptick on the y-axis: translation, improved performance over time . But performance of what, exactly? In the name of maximum efficiency, even the artist’s body can be turned into a measurable commodity. The human subject becomes an object, with no essential status difference between man and machine.

When infrastructure works, it’s like a discreet messenger angel: it recedes from view as the transmission is relayed, quietly operating all around us at a scale beyond our capacity to perceive.

Koetting’s genius lies in playfully unraveling the profanity of such a worldview, exposing it like a visible Ethernet cable. In Make up room (2023), a row of pink Polly Pocket-sized chairs sits empty before light-up mirrors framed by marquee bulbs, all powered by a web of white wires stretching back into the wall. Here, we see not just the backstage, but the backend , the technological “stuff” that’s usually hidden away. And yet, as Koetting makes the inner workings of his handmade computers partly visible – we joke on a WhatsApp call that this is ultimately a show about cable management, with cords placed conspicuously, as carefully as floral arrangements – he also takes care to conceal certain components and to ensure that certain processes remain out of sight.

The show’s title, “Unattended Access,” promises something revealing. It flatters a viewer’s fantasy of omniscience, casting us as giants, granting us a backstage pass. But still, it only teases the gods-eye view, the true position of privileged access. We will never be able to witness a network in its entirety: a hyperobject too large to be observed in one place at one time. And usually, the point of infrastructure is that we only notice it when it breaks down. When it works, it’s like a discreet messenger angel: it recedes from view as the transmission is relayed, quietly operating all around us at a scale beyond our capacity to perceive.

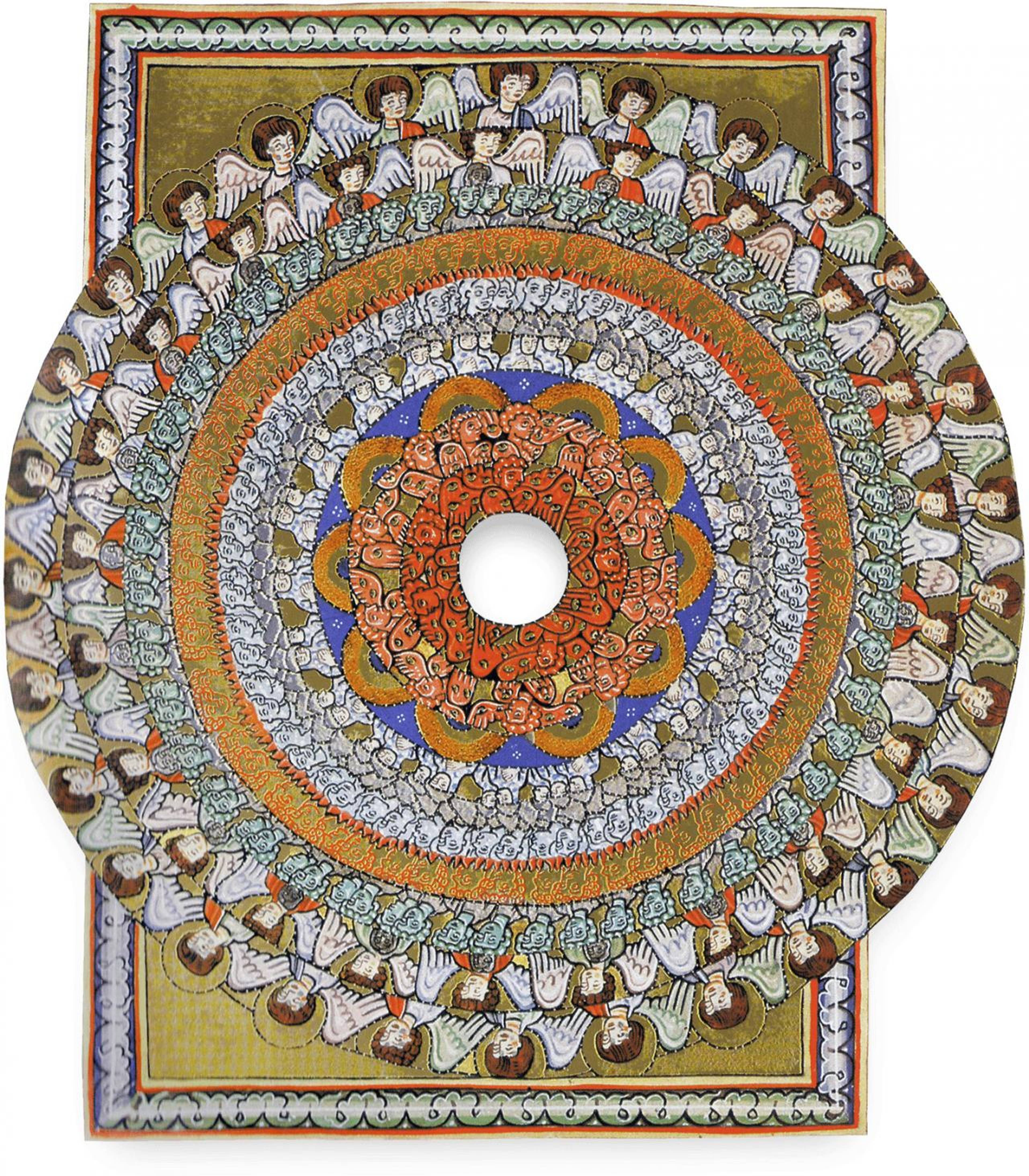

Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias I.6: The Choirs of Angels, 1150 ink and gold leaf drawing

Something about the cosmic exoskeleton of communications technology, banal and material as it may be, strikes me as mystical. Terminology like “planetary-scale computation” doesn’t do justice to the awe it ought to inspire. Perhaps a more apt metaphor for the material of the internet would be Hildegard von Bingen’s Choir of Angels , an illustration from the twelfth-century Benedictine polymath’s Liber Scivias. In it, concentric rings of beings surround a glowing core. They encircle it, orbiting it like satellites, strata of increasing holiness, layers of a spiritual Stack. Scivias was the first book Hildegard wrote, meticulously detailing the visions she’d had since her childhood. She took ten years to write it – a divinely inefficient project. Later, it was illuminated with illustrations like this one: a mandala of micro-and-macrocosms, all interlinked.

As it happens, a reproduction of this codex, open to precisely this page, sits on the first floor of “Au-delà,” a group show curated by Agnes Gryczkowska sprawling across three levels of Paris’s Lafayette Anticipations. Drawing together disparate works – from Hildegard’s grimoire to Silueta Series videos by Ana Mendieta to a haunting organ composition by the contemporary American musician Kali Malone – “Au-delà” deals in rituals across epochs. “Let us touch the things of sublime mystery that flutter in the periphery of our vision,” Gryczkowska entreats in a text opening the accompanying catalogue. Reading that line, I can’t help but think about infrastructure.

there is something legitimately demonic in networked culture’s pervasive reduction of everything to data – words like “connection” robbed of meaning; conviviality flattened into frictionless exchange.

Early in the show, a series of etchings by Janina Kraupe-Swidrska (Metamorfozy IV, V, and XII , all 1963) track flashes of energy, channeled mark-making: sigils that the artist was moved to make after her son’s unexpected death. The resulting, enigmatic forms could read almost as performance scores, embodied memories of movement. At the same time, in their diagrammatic quality, they might be said to resemble – albeit anachronistically – flows between nodes on a network.

Upstairs, Kat Lyons’ Death of a Comet (2022) indexes a similar interplay between celestial and earthly forms. In the painting, a single seashell is blown up to planetary size, circled by a fiery beam of light. Lyons was inspired by dark matter – the invisible substance that makes up most of the cosmos, uniquely detectable on earth from labs located far, far underground. The rocky terrain that we stand on holds the memory of the Universe’s making, she seems to say – a memory that, I would add, is thus also embedded in our machines, in their aluminum cases and lithium-ion batteries, embodying the eternal tug-of-war between dirt and ether.

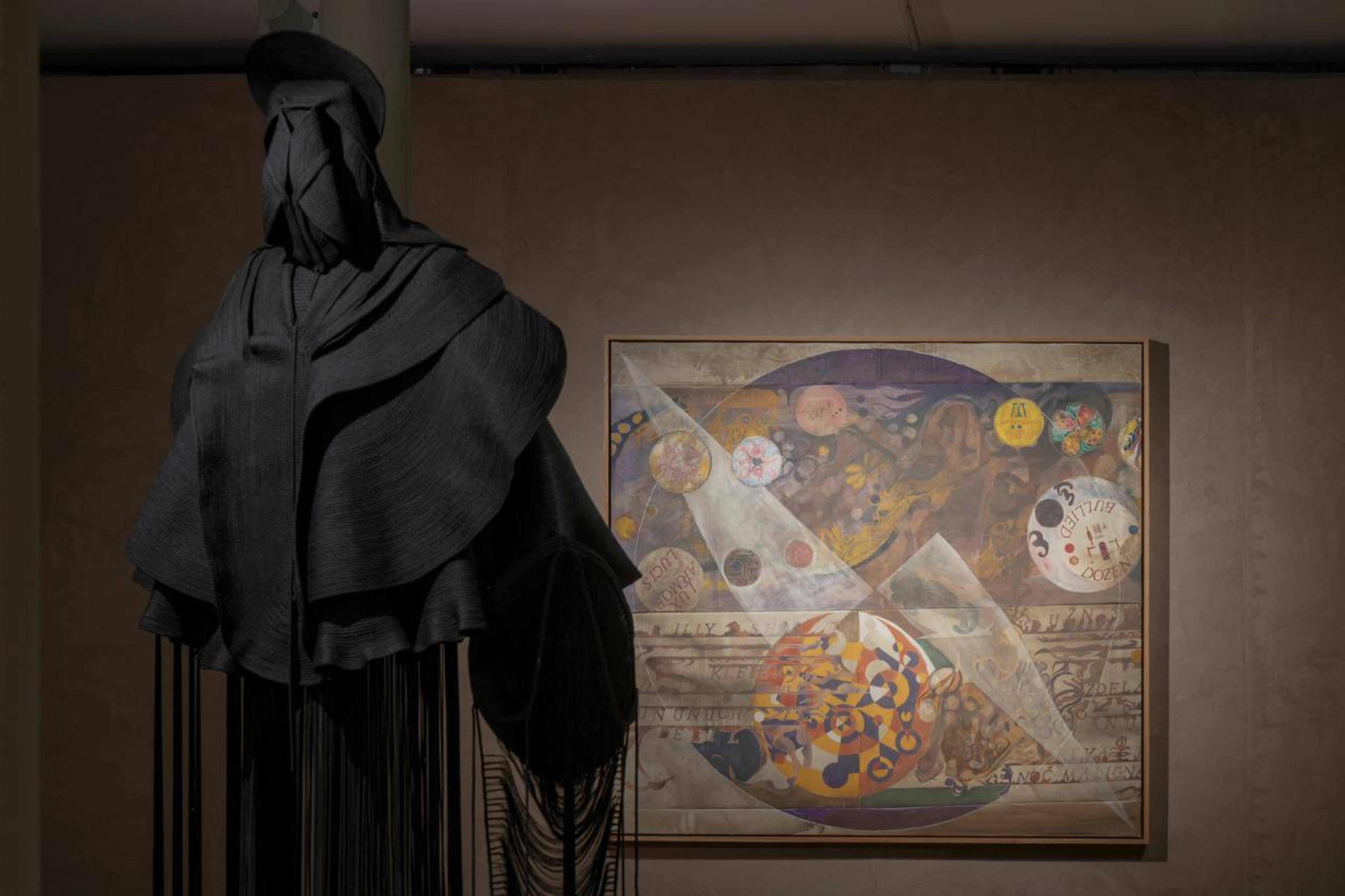

View of “Au-delà. Rituals for a new world,” Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, 2023. Courtesy: Lafayette Anticipations. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Esoteric musing aside, I think there is something legitimately demonic in networked culture’s pervasive reduction of everything to data – words like “connection” robbed of meaning; conviviality flattened into frictionless exchange. The Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner wrote – in a lecture that some of his followers have since come to read as anticipating the internet – of a “web of terrible spiders, spiders of enormous wisdom” that will one day cover the earth, cannibalizing it, ensnaring humankind with their devilish trickery. In essence: a World Wide Web giving rise to new, emergent intelligences that pose spiritual threats to the human. Some of his followers, joining the aforementioned “internet is made of demons” camp, see the digital as an embodiment of Ahriman, Lucifer’s counterpart associated with dyads and opposition – and thus, they argue, with computation: everything stripped down to binary data, decomposed into the ultimate dyadic opposition, zeroes and ones.

Songs for Living (2021), a video by Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic, appeals to the essential mystery of spiritual rite and truth in an age where machine “intelligence” demands to know everything, reducing humans into psychographic data. In the third and final floor of “Au-delà”, visitors spill into a space bathed in LED light, the color of which I can only describe as the default color of hyperlinks. Suffused with imagery of bonfires, burning wings and fallen angels, its haunting visuals gesture towards gravity and grace as the voice-over speaks of dissolving the self; divine transmutation. It’s a death-and-rebirth cycle playing in a womb-room lit in tones of Net Art Blue (which before that was called Yves Klein Blue), the color of unbridled immaterial exchange. In one of many moments that brought to my mind the Christian philosophy of Simone Weil, Arunanondchai and Gvojic’s video instructs us to “participate in the creation of the world by de-creating ourselves.” I hear it as an injunction, along the lines of Bernadette Corporation’s one to “Get Rid of Yourself” two decades earlier, against the nascent pressure toward hyper-individualization emerging from global informational flow.

The fantasy of total “unattended access,” which Koetting teases only to undermine, harmonizes with the many moments across “Au delà” where human finitude is brought up against the timeless, the boundless and the infinite. These two (very different) shows share an orientation toward something beyond mere networking when they speak of connection. Both bust us out of the Ahrimanic grip of illusory omniscience, highlighting the gap between data and truth. Each, in its own way, points to some kind of aporia, the indices of “sublime mystery that flutter in the periphery of our vision” – to that big ineffable something, our dumb little human subjectivities dwarfed in the face of forces that cannot be extracted, algorithmicized, or management-consulted into oblivion.

View of “Au-delà. Rituals for a new world,” Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, 2023. Courtesy: Lafayette Anticipations. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

View of “Au-delà. Rituals for a new world,” Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, 2023. Courtesy: Lafayette Anticipations. Photo: Martin Argyroglo

Kat Lyons, Death of a Comet, 2022, oil on canvas, 203 x 228 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

___

“UNATTENDED ACCESS”

Parliament, Paris

17 Mar – 6 May 2023

“Au-delà”

Lafayette Anticipations, Paris

14 Feb – 7 May 2023