The humble-struggle meal received a ritzy rebrand this summer. Timed to the peak of “it’s so hot out that I physically cannot imagine using the stove” season, the New York Times Styles section reported on a phenomenon, bubbling out of the primordial cultural ooze that is TikTok, named “ Girl Dinner.” TL;DR: It’s not a snack plate or a cheese board, but a third, more sophisticated thing. Think: whatever little scraps you eat when your boyfriend is out of town and you can’t be bothered to preheat an oven. Per the paper of record, it’s “an aesthetically pleasing Lunchable.” And, perhaps because it invokes the hot categories of femininity and youth, Girl Dinner has conjured no shortage of discourse.

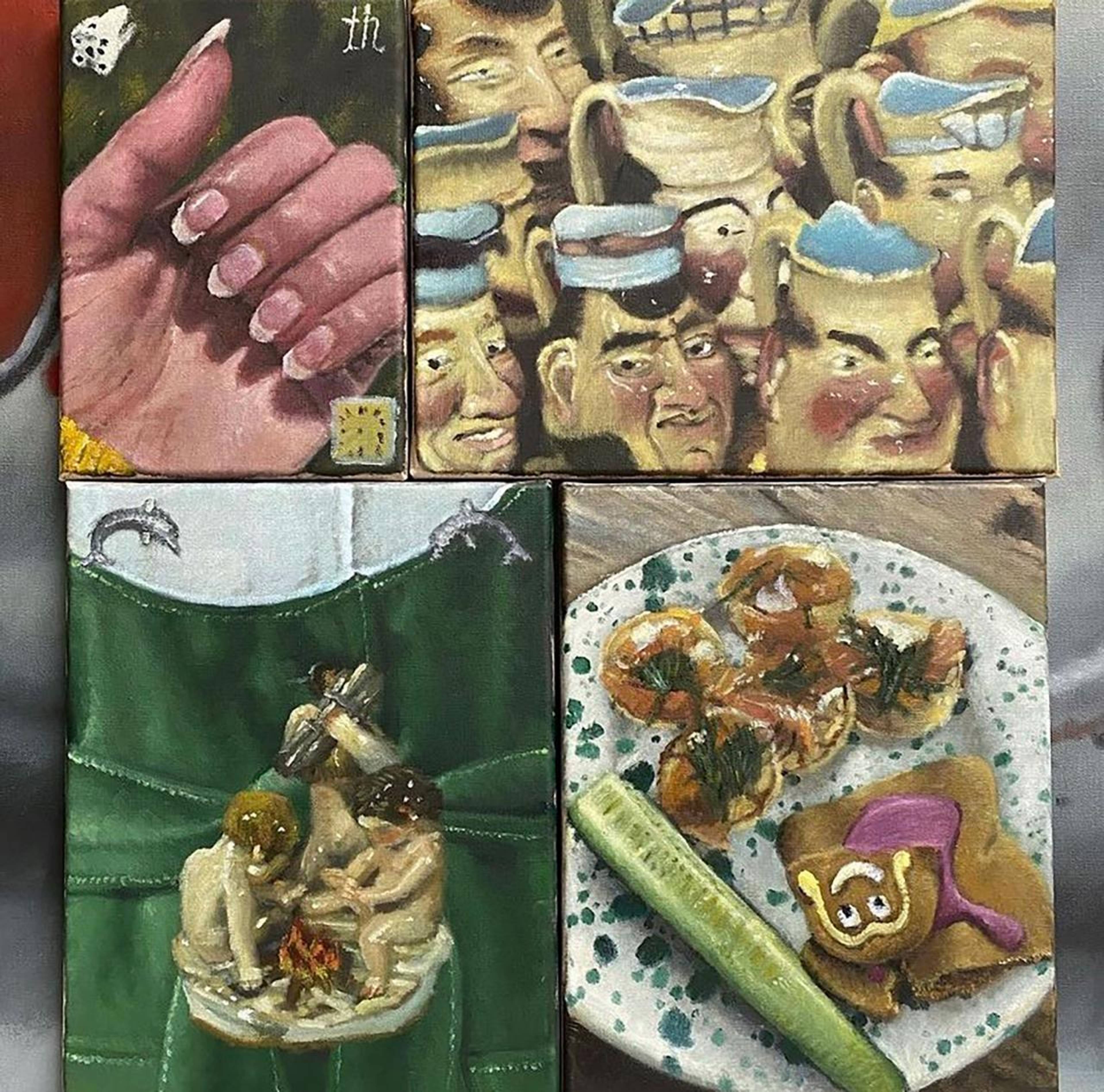

For a solid week in the wake of the Times piece, nary a meal is served in my vicinity – regardless of time of day or gender identity of company present – that is not referred to as a “Girl Dinner.” Here is a partial taxonomy of GDs I’ve recently engaged in (“eaten” would be too generous a verb): A large quantity of olives (recall that, before the media formalized Girl Dinner, there was always the expedient option of eating “ 30 to 40 olives ” that you “will certainly not regret”); roasted artichokes so velvety they look like they belong in a Renaissance painting – lacking the scrounged quality of classic Girl Dinner, but ruled as kosher GD anyway because “they seem like what someone might eat in an Ottessa Moshfegh novel”; and a spread consisting of a large, soft pretzel, a salami stick, and a single strawberry. All, of course, served with wine; always leading to a greater-than-intended degree of intoxication.

Over an OG GD (double-digit quantities of olives) at the skin-contact wine bar, my friend speculates that Girl Dinner satisfies some innate hunter-gatherer impulse. Basically, it fulfills the intrinsic urge to forage for and subsequently present an array of sticks and leaves, justifying it as a legitimate, civilized meal by plating it attractively. It’s parsimonious, drawing on scraps. It is defined by its open-endedness – a choose-your-own adventure – though limited by the constraint that it should not require silverware.

Evidently, GD’s ontological edges are a little blurry. Popeyes, the fried chicken chain that is confusingly named for a sailor who loves spinach, even went so far as to introduce a Girl Dinner menu. It’s really just a selection of existing side dishes, a sensible portion of mac n’ cheese plus two forms of potato, with an aftertaste of opportunistic marketing. As is so often the case with corporate PR departments’ attempts to realize internet trends, they have followed its form to the letter, but so blatantly missed its spirit.

Photo: Adina Glickstein

Obviously, GD is available to be eaten by anyone, irrespective of age or gender. Its eater’s identity as a consumer – of TikToks and legacy news media as much as of actual food – is precisely the one that matters. Just like Tiqqun’s Young-Girl, GD may have originated in behaviors associated with youth and femininity (though I sense some latent misogyny in the implicit assumption that “women” become “girls” when they downscale their domestic efforts, i.e., say fuck it and eat snacks for supper). But whatever relation to gendered roles it may once have borne, Girl Dinner, just like the Young-Girl, quickly became generalized to “the model citizen as redefined by consumer society.”

Despite its foraged mentality, I’d argue that GD is actually more postmodern than prehistoric. Soft factors like selection, arrangement, and plating are as essential, judging from the TikToks now populating the #girldinner tag, as the actual ingredients involved. Its combinations of culinary flotsam achieve value and desirability only by being reorganized into a defensibly coherent whole. It’s about referentiality – did it preexist its definition via meme? It is modular. It is inescapably self-conscious. Consumption becomes an opportunity for something resembling curation. At its core, it’s more about organizing signifiers than fulfilling a biological need for nourishment. It generally provides something only vaguely resembling sustenance.

Girl Dinner is not so much a meal as a mentality, the kind of thing that gives birth to neologisms like “tablescape.”

GDs are not cooked, then, but designed – design, here, deployed in the sense that Hal Foster intends when he talks about Martha Stewart and Microsoft: the fixings of a life thoroughly penetrated by market capitalism, resulting in a “near-perfect circuit of production and consumption.” It’s not so much a meal as a mentality; the kind of thing that gives birth to neologisms like “tablescape.” GD is a mindset shift, maybe even a manifestation. What it fails to offer in physical satiety, it might deliver in spiritual sustenance – a sense of purpose flooding my body as I arrange the dregs of last week’s grocery haul with a kind of care approaching Laila Gohar -esque levels of aesthetic consideration. Girl Dinner epitomizes the aphorism, increasingly common to the Instagram age, that “the camera eats first.” It lives on in its afterlife as a video played on eternal loop. Girl Dinner is eaten in full awareness of the fact that, today, consumer choice is treated like it’s tantamount to freedom.

An essential dimension of Girl Dinner: It’s about eating things that, for whatever reason, one is usually ashamed to be perceived while consuming – and even relishing it, elevating it to the level of celebratory indulgence. You can feel the giddiness emanating from certain videos, their creators rejoicing in an extra-heavy pour of chardonnay alongside their cracker plate, in what is made out to be a moment of femme solitude, as if they were keeping a secret – except they’re doing the opposite, posting about it on the Internet. Thus, Girl Dinner is inextricably tied to the field of vision. It’s meant to be eaten alone, yet it exists relationally, always keeping the gaze of the Other in mind. That could be the cohabitating partner whose absence permits you to prepare a meal that was previously below the threshold of socially acceptable meal-ness, or the imagined spectator double-tap hearting a video showcasing an especially well-laid spread.

Popeyes “Girl Dinner” menu

Confession: In parallel with (or maybe because of?) GD’s rise, I got sucked into Tinned Fish TikTok. This zone of the internet is exactly what it sounds like: dedicated to sourcing and reviewing the most exotic and esoteric in shelf-stable seafood. The algo served me vids after vids about the price-to-protein ratios of canned sprats, alongside art directors breaking down the visual lexicon of classic sardine-can design. Real GD heads will remember how, in the good old days (2018), Dasha from Red Scare had an alt account made famous on Food Twitter (explanatory tagline of the subculture: you eat it, you tweet it) and all the wannabe post-Slavic shorties got super into canned fish, following her example. Myself included.

Sardines, I would wager, epitomize Girl Dinner. Partially, this is thanks to their status as a no-cook protein and tendency towards attractive packaging. But on a deeper level, they underscore the kernel of GD. They are, after all, the food of visibility par excellence. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan explains his notion of “the gaze” – not merely eyesight, but the targeted awareness that, in looking, one is also looked at – by offering an anecdote. One day, out at sea, his eye is caught by a metallic object floating in the water, glinting in the sun. As he registers it, its reflection in the light seems to “see” him back. The piece of ocean trash in question? A discarded sardine tin, reminding him that to see is necessarily to be seen. What could be more native to a self-conscious smorgasbord? Tinned fish, the quintessential meal of girls and gaze.

A tin of sardines out at sea

___