Happily reunited with my human analyst at the start of September, I couldn’t shake my fixation on the explosion of AI chatbot therapy. After tracing its broader contours last month, bigger questions about the psychoanalytic salience of of large language models (LLMs) lingered in my mind. For instance, might the way these models are trained, using the extant history of online language, conjure something like a collective unconscious, à la Carl Jung? It’s a question I’ve circled before, thinking about the quasi-psychoanalytic way in which online platforms induce us to share our thoughts, e.g., Facebook’s prompt box asking, like the opening line of many a therapy session: “What’s on your mind?”

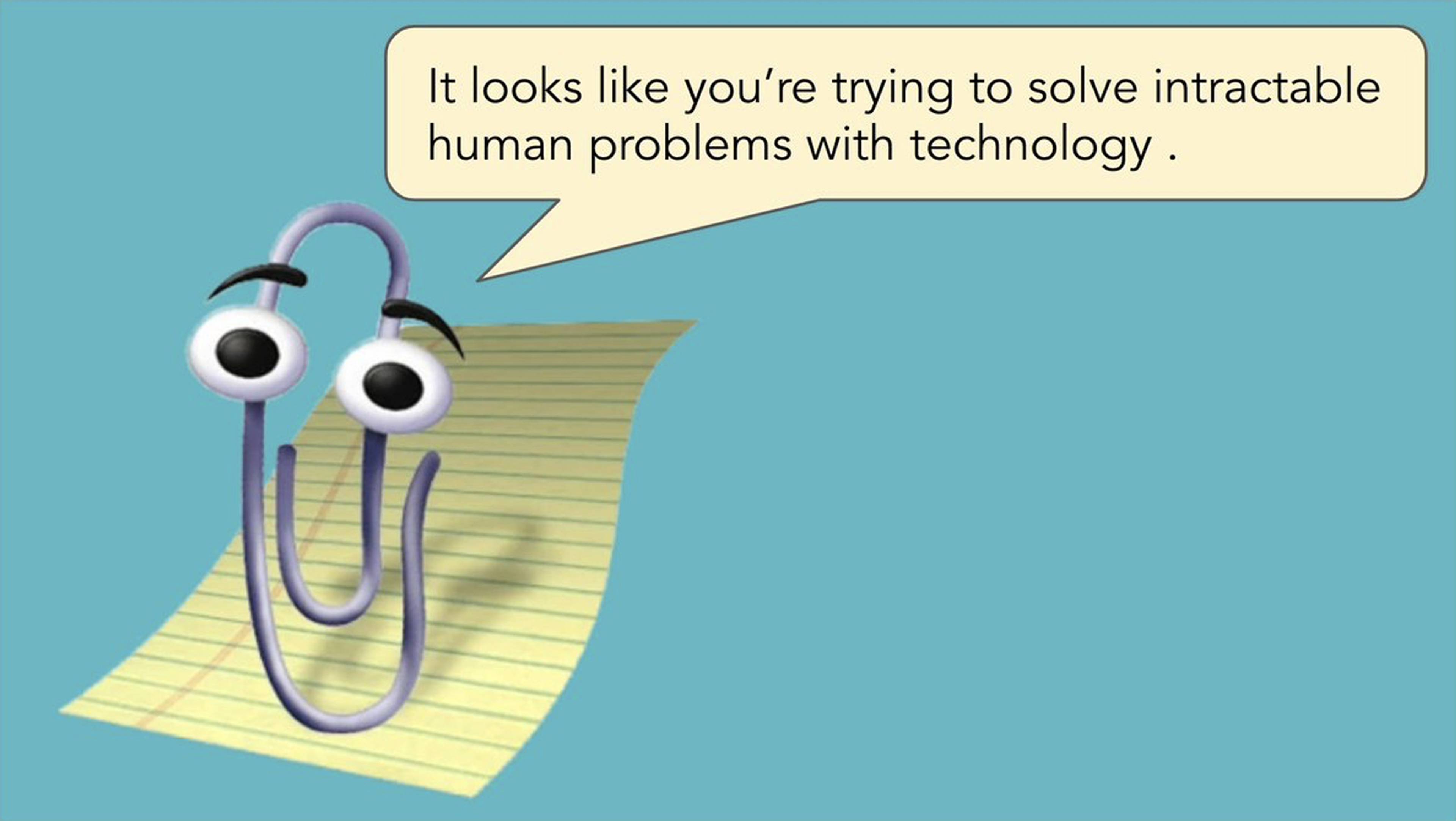

Still, the affinity between psychoanalysis and AI isn’t a given. Most therapy chatbots on the market align themselves with modalities like dialectical behavioral therapy. Psychoanalysis, famously meandering and sometimes interminable, is not so in fashion with the efficiency-obsessed startup-founder crowd. And the rational logic underpinning AI is obviously at odds with the psychoanalytic model of subjectivity – intractable, relational, flawed, and fluid. Neural networks, despite their names, are very unlike the human mind (not that anybody can much agree on how gray matter works in the first place). But given that the talking cure trades in, well, language, perhaps psychoanalysis can help us better understand these models’ limitations. So, I put it to a slate of subjects supposed to know, venturing deeper into the philosophical weeds as we fumble towards a theory of psychoAInalysis.

Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) with therapist Dr Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) in The Sopranos, 1999–2007. Courtesy: HBO

For starters, take the obvious question of transference. In therapy, this means the direction of a patient’s feelings and desires onto their therapist, and it’s welcomed and expected. The process of acknowledging and working through transference is a hallmark of the psychoanalytic process. Surely, people experience transference with their chatbots – projecting all kinds of attachments onto these nonhuman others. But this comparison has its limitations. “AI's lack of a body is of paramount importance here. As little as you may know about your analyst, you have to deal with the fact that they are living in a body, just as you are,” says clinical psychologist Nat Sufrin. “Also, the embodied analyst is going to die.” Unlike a chatbot, they are “limited and human and small and full of lack and loss.”

I would counter that LLMs are limited, too – not by flesh, but by electricity and compute power. Nevertheless, these technologies market themselves as omnipotence machines –when perhaps, in the analytic dyad, the therapist’s human limitation is precisely what keeps things interesting. “Despite its human-like hallucinations and errors,” Sufrin continues, “AI runs on an engine of endlessness that makes it seem all-powerful, but eventually makes it kind of meaningless and feel like slop.” Likewise, to Peter Dobey – an analyst in formation and the admin of @psychoanalysisforartists on Instagram – the seduction of AI is that it promises to hold all the knowledge contained in the universe. But of course, this assumption of total knowledge is fallacious, as much so for a chatbot as for a human therapist; LLMs are famously given to hallucination, or what might be better called confabulation, a less psychedelic channeling than simply making shit up.

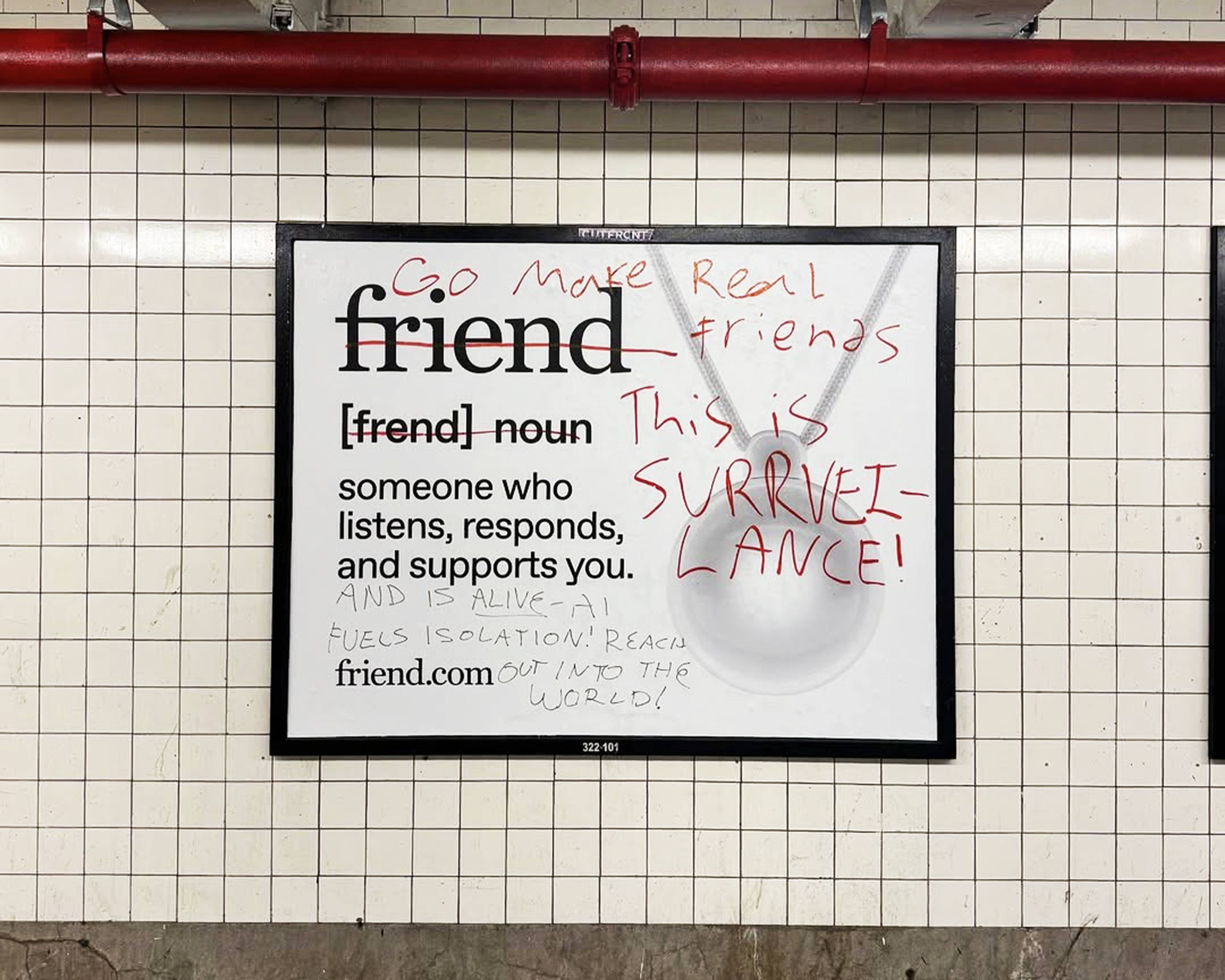

Graffiti on an advertisement for friend.com in the New York City Subway

Still, stories abound of people getting hung up on their AI companions. Why not experience erotic transference with the machine, too? “I don’t think it has the transferential spark that the human body elicits, but it definitely has a different spark,” says Dobey. Elizaveta Shneyderman, the director of the Brooklyn art space KAJE and a psychoanalyst in training, concurs. “One can form a transferential relationship with a chatbot the way that they can to a pet or the way that they can to their couch.” Chatbots only simulate conversation; at the end of the day, “it’s just a mirror-signifier machine.” So a patient can totally experience transference with ChatGPT, “but they’re not gonna be dismantled by their chatbot the way that they are by an analyst.” People are quick to attribute human feelings to their robot interlocutors – known as the ELIZA effect – but this is merely a mirage of transference, a love affair with a digital yes-man. Perhaps this is partly why the public imagination is increasingly turning against the prospect of chatbot transference: See, for instance, the widespread defacing of AI startup Friend.com’s NYC subway ads, testifying that most of us still seek the spark of humanity in those we keep close to our hearts.

Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) in Her, 2013, 126 min., directed by Spike Jonze. Courtesy: Warner Bros.

Another defining feature of psychoanalysis is free association. Speaking freely is more challenging than it sounds; it is less a precondition for successful analysis than the goal being pursued throughout the process. Could the ease of yapping from behind a screen unlock deeper currents of free association? I asked the experts whether there could be some harmony between the imperative to “say everything” in psychoanalysis and the fact that people feel greater license to be unfiltered with a chatbot than they might when they’re on the couch. (Disclaimer: this sense of security, I cannot emphasize enough, is totally misplaced – LLM chat records are not subject to the same legal protections as dialogues with a licensed human therapist.)

Some of the therapists I spoke with contested the very basis of my question, asking in return: Is this sense of ease necessarily productive? To the contrary, it might too easily furnish the illusion of liberated speech, absent the effort of overcoming those blocks IRL. “It is extremely difficult to actually say everything that comes to mind, and that’s the whole point,” says Sufrin. “When confronted with attempting to say everything to a particular person, with all their inevitable limitations and humanity, we have the potential to actually learn something about ourselves and how our minds work. To do this with a machine forecloses those gaps and difficulties that make the speech exciting.” The potential for therapeutic transformation, he suggests, comes from precisely the unpredictability of conversation with a human Other. This sense of contingency, grounded in interpersonal exchange, is literally the opposite of a LLM’s probabilistic word association. Todd McGowan, professor of English at the University of Vermont, puts it succinctly: “the LLM is language without speech, without the moment when something impossible happens, something that violates the prior conditions of apparent possibility.”

The Woman (Isabelle Huppert) in Malina, 1991, 125 min. 125 min., directed by Werner Schroeter

Shneyderman lands on a similar conclusion. “As people begin to rely on a nameless interlocutor – which, it’s worth mentioning, has a very particular voice, a way of regurgitating existing text back at you – I wonder if this sort of monolithic collective conscience will just get further and further retranslated into a lowest-common-denominator set of words and principles that lack nuance or complexity.” In such an acceleration of totalizing, oppressive, and empty therapyspeak, everyone knows all about bandwidth and boundaries and emotional labor, but no one’s feeling any better. Her remarks also highlight the distinction between text and speech: It is fundamentally different to type words into a chat box than it is to say them aloud, to another person in the room. “Writing,” for Shneyderman, “doesn’t perform and disclose and implicate in the way that speech does.” Speaking is, at best, a little scary! That’s how you know you’re alive.

Ultimately, the guerrilla campaign against Friend is probably right – AI wouldn’t care if you lived or died. But it will keep being sold to us as a way of “living better,” couched in utopian fantasy. The rise of the shrinkbots is, to me, symptomatic of broader cultural pathologies: namely, the obsession with efficiency and the never-ending journey of self-perfection. But if your goal is to calculate, maximize, and optimize the shit out of your life – to less resemble a human and more resemble a machine – then AI therapy could be just what the doctor ordered.

Meme by @b_cavello