This world of ours has acquired a thick film of vulgarity that imbues a spiritual man with all the violence of passion. But happy are the shells which the poison has not entered.

– Charles Baudelaire in his 1857 preface to Le Fleurs du Mal

The day was long and sultry. A late summer heatwave brought the Vienna cognoscenti out in force to the Hotel Almanac’s well-appointed ballroom for the opening of Curated by. It was the boozy relief of a trippy night – the last waltz of the artists, gallerists, curators, and various other personae. Suffice to say that the annual festival is, by now, an august institution. Its mandate is to invite (mostly) independent curators to produce thematic exhibitions in cooperation with participating host galleries. Most importantly, it utilizes the city’s built-in exhibition infrastructure and provides the financial muscle to invite new or rediscovered perspectives; the curator’s task, in turn, is to keep it fresh, by introducing artists who may not otherwise show in Vienna. They are tastemakers in the culture-at-large, and, with their writing and publishing activities, the intellectual backbone of the art machine. Underpaid as curators generally are, Curated by honorably fulfills its fiduciary duties with respectable honorariums and transport budgets.

The 2023 edition takes a sober look at today’s reality through the rear-view lens of “The Neutral,” its framework built around an eponymous Roland Barthes text that was met by participants with both skepticism and intrigue. One curator dismissed it as a provocation, saying the “world is on fire,” while another said it was a timely subject to consider. What, then, is the neutral in application? It’s neither realpolitik rapprochement or détente, nor is it a promulgator of mercantilism; instead, it fence-sits the Freudian polarities of the ego and id. It’s the mask of cordiality, and the mirth of a baroque Noh theater with rules to the game. When things get misconstrued, it puts a shell on to keep the poison out. Ultimately, on the chessboard of curating, things flesh themselves out; what you see is what you get.

View of Na Mira and Patricia L. Boyd, “Perpetual Language,” curated by Quinn Latimer, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2023. Courtesy: the artists and Croy Nielsen, Vienna. Photo: Kunst-dokumentation.com

Patricia L Boyd, 79. Paranoid schizoid position, 2023, moving box, plywood light box, prints, fork, glass, 32 x 82 x 38 cm. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Kunst-dokumentation.com

Literary and film connections pervade many of this year’s exhibitions. In Quinn Latimer’s “Perpetual Language” at Croy Nielsen, Patricia L. Boyd (*1980) and Na Mira (*1982) offer a compelling estrangement. The latter’s split-screen, single-channel, film-transferred Marquee (2023) is ingeniously placed catty corner in the gallery’s darkened main room. It borrows the deconstructive tropes of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s unfinished film White Dust from Mongolia (1982), haunted by the latter director’s ghost: A performer’s non sequiturs hover onscreen, then disappear across a large floor mirror, while a pair of lo-fi AM radios broadcast from a local frequency, creating a sculpturally dissonant soundscape. The space is ambiently permeated by the intermediary red of photo labs, the painted-red projection screen further dramatizing the fragmentary narrative and the specter of disembodiment.

Meanwhile, Boyd’s corridor of floor-set cardboard-lightbox sculptures are self-contained memory holes. Peculiar and low-tech, each is a well-used readymade, modified and repurposed in the guise of five moving boxes (NY to London) complete with tape, scrawly handwriting, and company logos, alongside a similarly sized, precisely built wooden box. Both have plexi-tops with objects entombed across a loose bed of feathers. They tingle with the angst of a dream turned nightmare on the wings of ecstasy and madness. You can get as Freudian as you want about the embedded joy of sex-mimeographed illustrations and inventory sheets; the cryptic forks and spoons Boyd leaves on the boxes’ outer flaps; or the detail photos of bed innards protruding like wounded flesh, while the row of tacks stuck across the edge of the finely hewed boxes is all punk. Yet, in their spatial compressions, their Judd-like repetition and seriality, these sculpted vitrines behave as staged three-dimensional photographs. The purgations of Boyd’s psyche are enshrined as talismans. In their trail of clues and cross-indexing there lies a lucid poetry and a method to her madness.

Moyra Davey, Fifty Minutes, 2006, digital video with sound, 51 min. Courtesy: the artist

In “Taking Notes” at Sophie Tappeiner, curator Theresa Roessler cites Christa Wolf’s Ein Tag im Jahr: 1960–2000 (One Day a Year, 2007), the impetus of which is an attempt at recollection and autobiographical truth. There, Moyra Davey’s (*1958) alpha-wave-inducing video 50 Minutes (2006) is a critique of psychoanalysis told in twenty mesmerizing episodes, its author confessionally soliloquizing her five-year experience of psychotherapy. Davey recalls pivotal moments in the unfolding stream of her life, commentates on current events (9/11 and its cultural after-effects), and cites from her reading syllabus (Natalia Ginzburg, Peter Handke, Hollis Frampton). She speaks in an even keel directly to the camera. Her untidy home is filled with dusty books. Pacing back and forth in her upper Manhattan apartment, she comments on childbirth, motherhood, and food. To make you feel intimate with her in her personal space is their artifice and achievement. In its hypnotic, episodic, smartly edited cadence, the twin mask of the artist remains, present and past oscillating as one thing.

Sophie Thun, Entered the Elusive Archive of Zenta Dzividzinska (Summer 2021)(detail), 2023. Courtesy: the artist

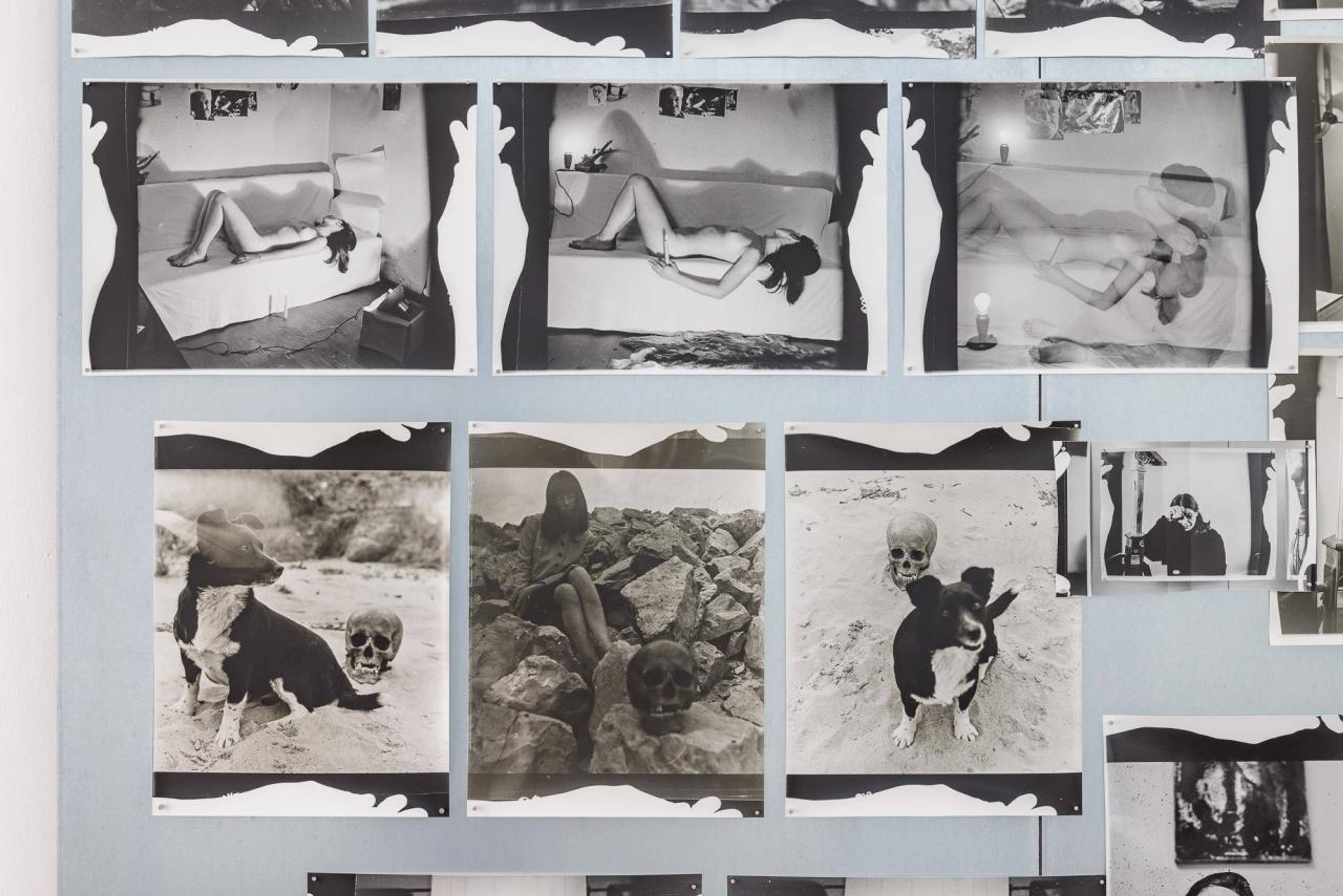

The artist Sophie Thun (*1985), who has done many analogic self-portraits, has worked in recent years with the photographic archive of the late Zenta Dzividzinska (1944–2011). Here, she has printed a selection of the Latvian photographer’s output and displayed them in loose rows across a large metal sheet held up by small magnets, a method she uses to select her own prints when preparing exhibitions, superimposing the living artist in a ghostly posthumous collaboration. Both focus the camera on themselves, using their bodies in staged settings to reveal the mechanical artifice of their trade. Her wall-hugging, large format Having Entered the Elusive Archive of Zenta Dzividzinska (Summer 2021) (2021–23) shows Dzividzinska in multiple poses, dressed and undressed, each photo printed with traces of Thun’s own hands at their edges. A symbiosis occurs, a doubling of self-portraiture; both homage and engagement, twinning the two artists in a very real conversation between the living and the dead.

Works by Fritz Panzer at the viennacontemporary booth of Galerie Krobath, Vienna, 2023

Works by Abdul Sharif Oluwafemi Baruwa at the viennacontemporary booth of E X I L E, Vienna, 2023

A break from the mega-watt curatorial showcase detoured me to viennacontemporary’s altogether more commercial undertaking, which, despite its location in the palatial, Renaissance-style Kursalon, can feel like a claustrophobic bazaar, though the addition of an adjoining tent did somewhat alleviate the crush. Meandering the walls and stalls of this relatively regional fair, the wily flaneur can point out diamonds in the rough of this quarry of contemporary art. The stand out Fritz Panzer install at Galerie Krobath showed his underappreciated virtue in two and three dimensions, including surprising photographic presentations of sculptural works in situ, à la Brancusi, and a deft touch in framed oil temperas. With its own idiosyncratic curatorial eye, E X I L E was awarded best booth prize with a solo by Abdul Sharif Oluwafemi Baruwa, who countered abject sculptures (a sawed tub on wooden mounts that, cut in half, had been made into seating) with small, quirky paintings, an art povera way with everyday material, and an insouciant outsider’s surreptitious social critique.

Layr debuted an ambitious segue from gouache on paper to canvas (actually linen) by Matthias Noggler, who went for the brass ring in a panoramic, two-panel horizontal painting of dense color accretions dominated by a lustrous cobalt blue, while shadowy, arm-linked protest figures (appropriated from a photo) foreground the flat compression of the rhythmically arranged forms. The Lisbon gallery Pedros Cera presented Adam Pendleton’s signature Black Dada silkscreens on Mylar and a folkloric, burnt-limewood sculpture by Paloma Varga Weisz; Peter Friedl’s kitschy cat-photo appropriations at KOW were a delight; and Zeller van Almsick’s combo of skeletal, totemic sculptures by Bianca Phos played well with big, lush, abstract paintings by Hong Zeiss. Ultimately, at the Torinese gallery Giorgio Persano, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s cheeky silkscreen on mirror-polished stainless steel, Selfie – autoritratto (2023), showed the ninety-year-old artist is very much in touch with the NOW.

George Tourkovasilis, Untitled (Contraposto-&-Pieta-I-II), n.d. Courtesy: the Estate of George Tourkovasilis, Radio Athènes, Melas Martinos and Akwa Ibom, Athens, and FELIX GAUDLITZ, Vienna. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

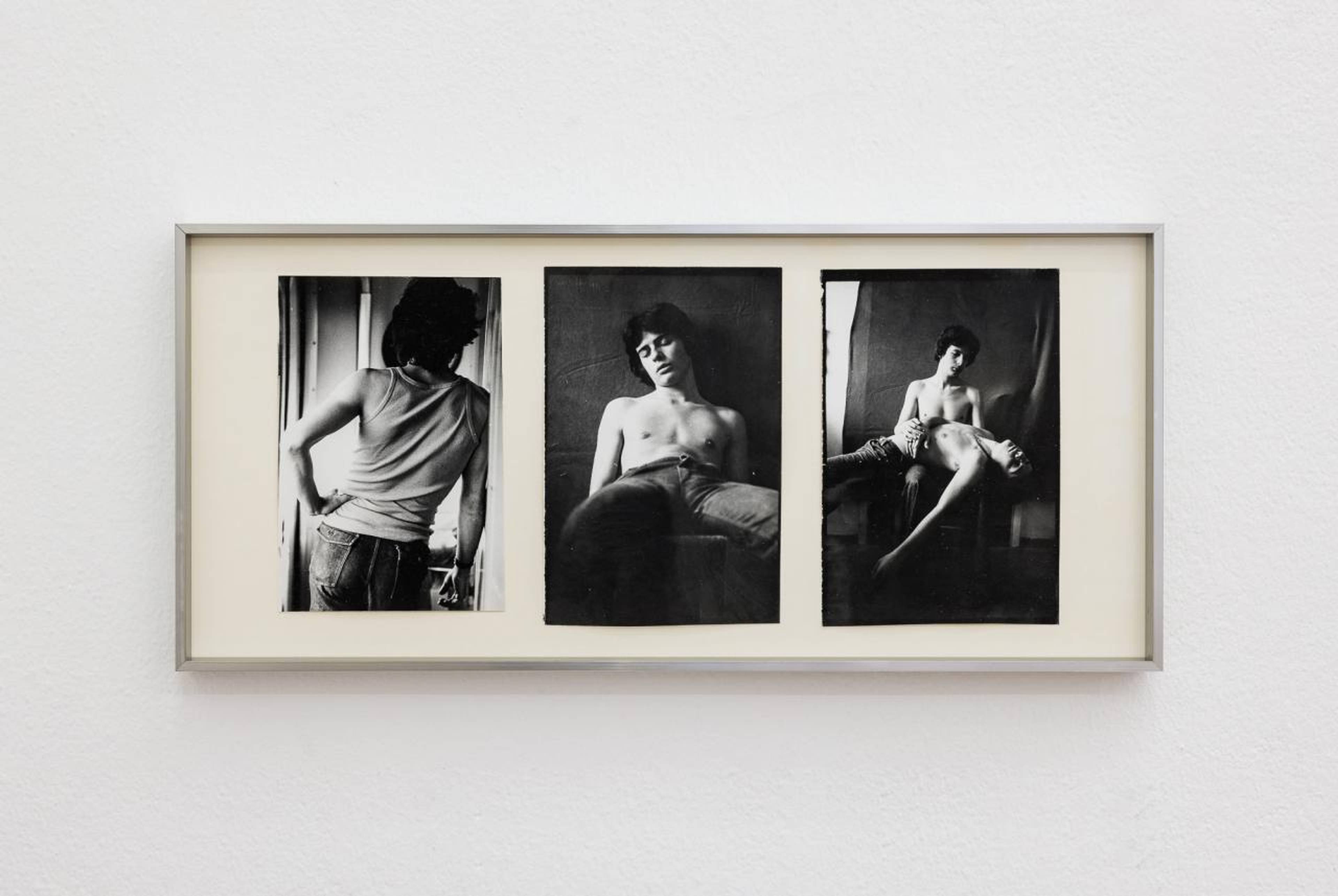

Again beyond the trade fair, the curator, a connoisseur and arbiter of taste seeks out the high, the low, and the road less taken to expand the definition of where art can be found. The central protagonist of Helena Papadopoulos’s “Ah This!” at Felix Gaudlitz is the author and photographer George Tourkovasilis (1944–2021), who lived between Athens and Paris, where he was an assistant to the Greek figurative painter Yannis Tsarouchis. Tourkovasilis quit a career in law to follow his muse, poetically chronicling in The Rock Diaries (1984) Athens’s thriving punk and new wave scene and composing a treasure trove of intimate portraits of studio models, friends, and his Paris-Athens demimonde. He stayed close to what he knew, his self-taught lighting wise in the manner of Luigi Ghirri or Stephan Shore. At Gaudlitz, his c-prints from the 1970s are saturated with rich Kodachrome colors, a hand reaching for a hard pack of Marlboros on a grassy knoll and the demure, erotic charge of a reclining lady showing a crystalline eye for the moment. The 80s brought a shift in style, with some later black-and-white pictures of male figures set up like classic advertisements. A fabulous image of billowing hair (Untitled, Shampoo , n.d.) and a homoerotic tryptic (Untitled, Contrapposto & Pieta I, II , n.d.) are more than a painterly Eros. They are a reminder that a literary mind and poetic soul know no separation between life and art.

Nick Irvin’s “Dowsing” at Layr is a bazaar chockful of ephemeral countercultural nods, fringe Americana, and delvings into conspiracies far and wide. Hence, Gene Beery’s (*1937) snide painting of former U.S. President Ronald Reagan, Where is the Best of Me? (1987–94) and Nativity Painting, Reggae Jam (2018), an unruly mixed-media install by dub king and collage artist Lee “Scratch” Perry (1936–2021). The dystopic video Grace/Graze(d)/Grief Complementary (2011–18) by SoiL Thornton (*1990) gets countered by Frances Stark’s (*1967) mixed-media video bricolage Argentina (2021), which isn’t neutral at all in condemning Henry Kissinger’s foreign affairs machinations in the 1970s.

View of “Dowsing,” curated by Nick Irvin, Layr, Vienna, 2023. Courtesy: Layr, Vienna. Photo: Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

Left: Reza Shafahi, Untitled, 2023, acrylic on paper 70 x 50 cm; right: Forugh Farrokhzad, “The Captive,” 1955. Installation view, Silvia Steinek Galerie. Photo: Simon Veres

View of “Between 58 and 131 infinitely,” curated by Luiza Teixeira de Freitas, Galerie Martin Janda, 2023. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com

At least since Mallarmé and the symbolists espoused to name no things except as symbols of unseen realities and mood, artists have looked to poetry for visual inspiration. Martha Kirszenbaum’s “The Captive” at Galerie Steinek pairs two melancholic poems by Forugh Farrokhzad (1934–67), “The Captive” (1955) and “Bathing” (1958), with graphic and colorful acrylic works on paper by Reza Shafahi (*1940) and inky blue drawings on paper and a video by Sadaf H Nava. The Iranian modernist poet’s enchanting words of lost love, carnal desire, and the barriers she broke through to publishing are heartbreaking, impeccable, and triumphant, paired with the Shafahi’s play with themes of artistic freedom and usurped taboos. Having turned traditional Persian art inside out, both artists refer to some of Farrokhzad’s poems, Shafahi with his folky, art-brut style and Sadaf H Nava with allegorical windows, curtains, roses, cherries, and female bodies depicting what words cannot.

Hopscotching around town, I felt like a Raymond Chandler detective, on the hunt for leads to the elusive neutral. I needed a stiff drink; loaded pen in hand, I fired away. In Luiza Teixeira de Freitas’s “Between 58 and 131 infinitely” at Galerie Martin Janda, the literary reared its gorgon head once again. Cued by Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch (1963), a labyrinthian book like a Chinese box, I looked at the metal-barricaded monochromes of Roman Ondak’s (*1966) two small-scale paintings, Erased Horizon and Blackout (both 2017). Refuting easy readability as either painting or sculpture, you could see these gems as being in that misty, grey nebula of the neutral. Encountering the framed Alejandro Cesarco (*1975) inkjet print Long Casting (A Page on Regret) (2019) connected all the indexical dots. A mapping of influences and syllabi, it struck me that dropping the “t” in neutral yields neural. And in the heady constellation of a networked flowchart, the combinations are endless, a Sisyphean pattern of input and output. Curating is all a game of nuance and correspondences. Behind every postulation, behind every facet of truth or fiction, at its best, we observe the ineffable, decry the injustices of the dispossessed, and feed off the recurrent feedback loop of the restless imago.

Works by Bianca Phos and Hong Zeiss at the viennacontemporary booth of Zeller van Almsick, Vienna 2023

Work by Matthias Noggler at the viennacontemporary booth of Layr, Vienna, 2023

Curated by: “The Neutral”

Various galleries, Vienna

12 Sep – 14 Oct 2023

viennacontemporary 2023

Kursalon Hübner, Vienna

7 – 10 Sep 2023