Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Memoria (2021)

“ELECTRIC CHAIR to everyone involved in this movie!” my friend Alexi writes in her Instagram review of Memoria (2021). “I literally want to cry thinking about the time I’ll never get back.” Memoria was my favorite film of 2021. I’ve seen it twice and would eagerly sit through it again. Starring Tilda Swinton as a woman with exploding-head syndrome, the film is slow in a welcoming, meditative way. Minute-long scenes pass where the main drama entails watching a dog follow Swinton’s character around, or she’s in an art gallery and suddenly some lights turn off. I could understand how sitting through it in the wrong mood could test your patience. But did my friend not know what she was in for?

Still from Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Memoria, 2021, 132 min., with Tilda Swinton. Courtesy: Kick the Machine, etc.

after a while because it was literally more interesting to look up at the sky.” Which begs the question: Where exactly had she seen it? “My friend dragged me along,” Alexi replies, “It was playing in the middle of a south Brooklyn cemetery.”

At which point I’m like, No wonder you didn’t like it. The film (I reiterate, the best of last year) is hyper-dependent on sound, which is so attenuated and jarring that to watch it outside of a proper theatrical environment is to lose track of its driving force. When the “boom, then kind of a bonk,” that catalyzes Swinton’s character also shudders through you, it should carry the weight of both a boom and a bonk. Thus tying you to her increasingly unreliable perspective and preparing you for the film’s salacious departure from realism in its sinuously symphonic finale.

“I thought it was a disgrace of a movie,” she tells me later. “It’s so boring. I stopped watching.”

In the wake of the great collapse between high and low culture, situational context is the last form of distinction.

None of which I told Alexi. She’s entitled to her opinion, and it’s quite possible that Memoria’s fable-like conceit about time and transcendence simply did not speak to her. But one of the things I believe about movies is that each suggests its ideal viewing experience, and that the context we consume them in will tell us a lot about how we’re going to feel. Just as sitting through a Buñuel in a sticky, soda-stained multiplex would be a cruel extension of that director’s bourgeois torments, taking in James Bond at a place where you can actually order a decent martini suddenly makes those films’ glamorous fantasies seem silly.

In the wake of the great collapse between high and low culture, situational context is the last form of distinction. To its credit, the art world has figured this out far better than the people who program and distribute films, which is why gallery screening rooms are so variable in terms of light, space, and seating arrangements — and almost always allow you the freedom to walk out of something you hate. At their best, films anticipate and inform these screening environments, and not just in special cases like Memoria that depend on a certain level of sensory deprivation to flourish.

Here are some of the movies I saw this summer, with my recommendations on the ideal ways to watch them.

Still from Joseph Kosinski, Top Gun: Maverick, 2022, 131 min. Courtesy: Skydance Media

Joseph Kosinski, Top Gun: Maverick (2022)

You already know what happens in Top Gun: Maverick. It’s the same as Top Gun, only the team is more divided, the assignment more dangerous, and this time they play beach football instead of beach volleyball. Tom Cruise’s Scientology-affected agelessness helps underscore the film’s familiarity in a way that is genuinely comforting, as though nothing important has changed since 1986. The idea of Cruise not saving the day — always a remote possibility — is unthinkable in this franchise; I was genuinely touched to see that not even the minor characters under his command die. Lots of recent war movies like American Sniper (2014) or The Hurt Locker (2008) pay lip service to the shitty way we now fight wars by incorporating isolation, moral bleakness, and unexpected death. Sometimes it’s just nicer to cheer on a story that is plain, untroubled fiction, not even deigning to say which “enemy territory” has been enriching its uranium.

Seeing it in IMAX is like being strapped to the side of a supersonic jet, while allowing you to quietly marvel at the fact that someone really did strap IMAX cameras to the side of a supersonic jet.

What has changed since 1986 is film technology. Maverick’s raging success in the box office this summer was helped by the fact that it genuinely has the edge on its predecessor in terms of stunts, cinematography, and sound. Seeing it in IMAX is like being strapped to the side of a supersonic jet, while allowing you to quietly marvel at the fact that someone really did strap IMAX cameras to the side of a supersonic jet. This makes for a deeply penetrating sensory experience akin to a sound bath. Not watching it in IMAX would perhaps make for a tolerable in-flight movie, but only because you’re airborne at the same time as Cruise.

Still from Halina Reijn, Bodies Bodies Bodies, 2022, 95 min. Courtesy: A24

Halina Reijn, Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022)

I recommend seeing Bodies Bodies Bodies in the opposite conditions from those in which I saw it: alone, outdoors, and freshly snubbed from the VIP section by an A24 intern. I sat near the back of the New York premiere, which took place at a fenced-in stretch of Fort Greene. On all sides, people with more foresight than myself clandestinely cracked open beers; up ahead, the blessed few who had met with the intern’s approval stretched out on a sea of branded beach towels. Meanwhile, on the other side of the fence, a small group of picnickers who hadn’t paid for the event cheered after one of them successfully wrapped his jean jacket around an obstructing streetlamp. There were three classes of citizen on this small stretch of lawn, and all of us got essentially the same view of the screen.

This was oddly fitting for a movie about Generation Z — digital natives obsessed with subjective moral hierarchies and all-too-objective metrics. Bodies Bodies Bodies is not the first horror film to unleash mayhem through gameplay, but it does contain a uniquely fresh perspective on the powers of gamification; unlike most of its genre peers, corpses don’t start piling up here due to some outside malevolence but because all the characters feel bound to continue with a cycle they neither enjoy nor can image transcending. In the process, each victim becomes an eventual perpetrator, making the whodunit aspect — and subsequent twist — genuinely funny and entertaining developments.

This parable of social media’s “circular firing squad” would best be enjoyed with a group of good friends and a case of cheap beer. The ultimate reward of the film is social; the characters all act in such bad faith to one another that laughing at their demise will bring you closer together.

Still from David Cronenberg, Crimes of the Future, 2022, 107 min. Courtesy: Neon

David Cronenberg, Crimes of the Future (2022)

In a way, it’s admirable that Cronenberg continues to make his creepy little B-movies with Hollywood money and star-power. As with everything else he’s ever done, Crimes of the Future was received poorly on its release and will age well, with midnight screenings stretching far into its twilight years. Cult viewership offers a different way of watching movies — one that reserves its adoration for the parts of the film that were initially panned — and this suits Cronenberg’s catalog particularly well. Our moment is sadly missing a sense of ironic distance about the fact that Viggo Mortenson and Lea Seydoux came together to play sexy gross lovers, while Kristen Stewart’s anxiously horny turn as a government scientist named Timlin is so excruciating that it basically makes the whole movie.

Cronenberg deserves real credit here for making the first body-horror movie about microplastics. In a typical move, this fascinating concept barely makes sense when it’s poured into actual plot, missing opportunities left and right to explore its most salient points. As an ideologue, he’s almost too good for his own good. In terms of realizing these ideas, his work is shoddy and often suffused with the ambient confusion of his cast and crew. My recommendation here is tricky, because Crimes of the Future is worth seeing in theaters but not really worth the price of a ticket. If you can’t wait twenty years for its revival-run era, maybe buying entry to Minions: The Rise of Gru (2022) and sneaking in would be a better allocation of funds? It would at least have the perversity of a Cronenbergian act.

Steven Spielberg, Jaws, 1975, 124 min. Courtesy: Zanuck/Brown Company Universal Pictures

Steven Spielberg, Jaws (1975)

This summer, the beaches of New York and Long Island closed several times due to shark sightings. The weekend trips my friends and I planned throughout the season invariably enlisted checking up on these sightings, and freaking each other out the few times we did make it in the water. As climate change increasingly makes such encounters possible, Steven Spielberg’s 1975 box-office behemoth increasingly seems like a parable about climate change. It is also very much a story about the hatred of animals, and of man’s anxiety regarding his own ignorance towards nature.

The film’s patent implausibility, diegetically described as the never-before-seen phenomenon of a man-eating shark in local waters, becomes a lot scarier in an age when previously unfathomable natural disasters are happening on a near-daily basis.

I recently saw Jaws in IMAX for the humble price of three dollars in honor of National Cinema Day, an American holiday that I suspect was invented as a marketing ploy. These heroic circumstances begged for a large popcorn, a Coca-Cola slushie, and a potent edible. If you can’t recreate such conditions in your homeland, my country would love to come and liberate yours. There’s a sickly pleasure in watching such a crowd-pleaser in a packed house, because some people actually know the lug-headed Jaws script by heart, and everyone cheers when they blow the shark up. But the film’s patent implausibility, diegetically described as the never-before-seen phenomenon of a man-eating shark in local waters, becomes a lot scarier in an age when previously unfathomable natural disasters are happening on a near-daily basis. I was genuinely frightened when Quint, the professional shark hunter, gets gobbled up alive right in front of his crewmates — I did not remember that part from when I watched this as a child. The edible-induced anxiety eventually culminated in paranoia about the movie’s climactic message, which also seems to have clarified with age: In the shark’s final hour, it was not the old sea-dog who ended everything, nor the scientific expert, but a white policeman unafraid to fire his gun.

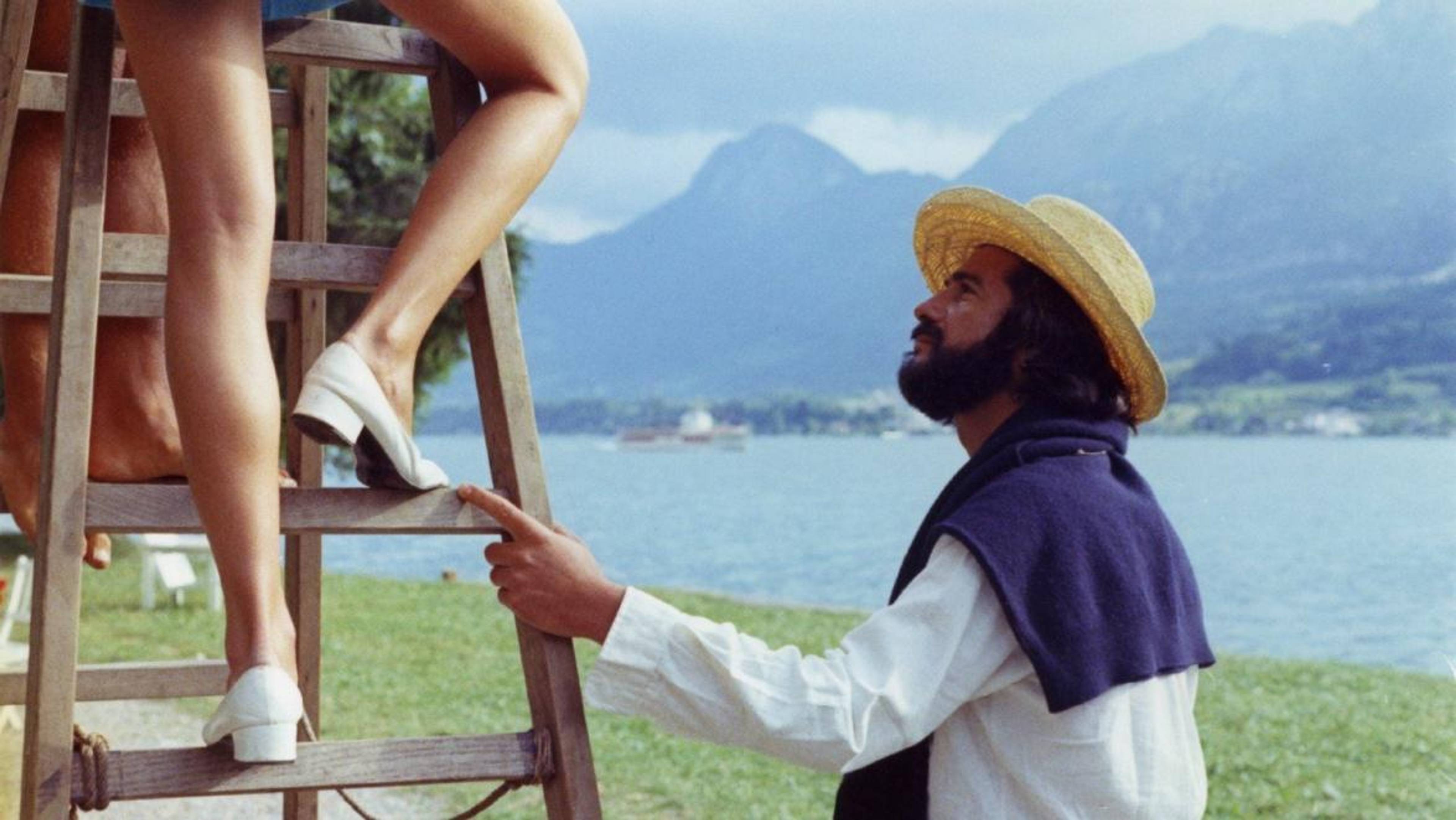

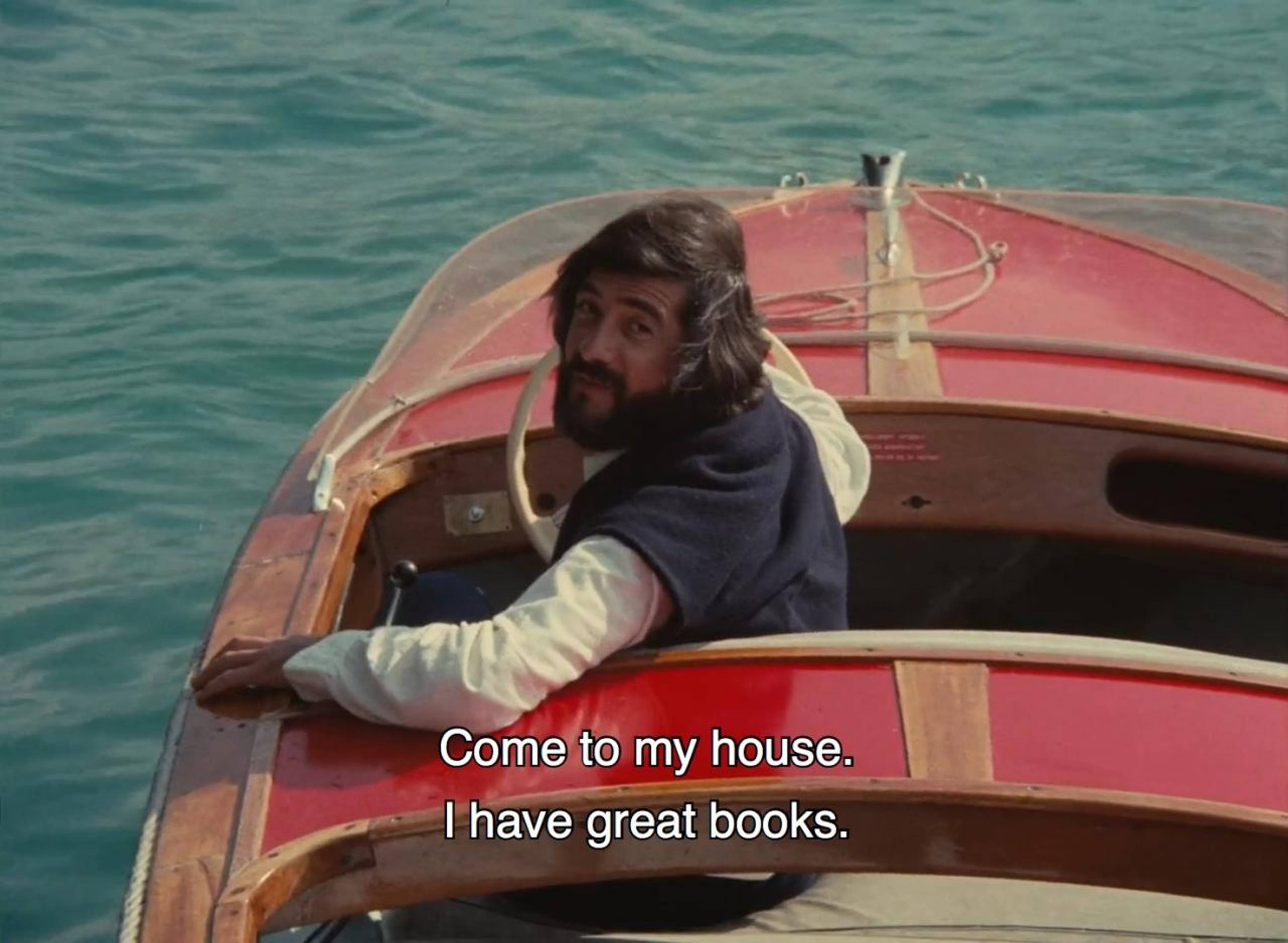

Still from Eric Rohmer, Claire’s Knee, 1970, 106 min. Courtesy: Les Films du Losange

Eric Rohmer, Claire’s Knee (1970)

The next time you end a relationship, or have one ended for you, I strongly recommend borrowing a friend’s Criterion login and watching Claire’s Knee — in bed, with your laptop on your legs. A romantic drama that avoids a love connection, Rohmer’s 1977 film is a study of mismatched relationships that will have you reflecting without nostalgia on your own, while also introducing you to the freedom and treachery of life as a single person. This might be kind of sad at first, but it’s cathartic too. At the very least, the movie’s beautiful. Summer may be over, and with it the love you cherished so dearly, but Rohmer’s celluloid daydream will never leave us.

In the film, a suave man named Jerome spends his summer playing with the feelings of a much younger girl, Laura, who has a big crush on him. Just when it seems like he’s about to go too far, Laura’s step-sister Claire shows up, with those knees of hers. They are indeed pretty, and Jerome is suddenly obsessed with them. Claire, on the whole, remains an impressively minor character; the film makes clear that, despite the change of focus in Jerome’s attentions, he cannot as easily alter the course of his machinations.

All of which makes for a surprisingly amoral moral tale, one that openly explores how weird and unassailable desire can be. My favorite part of the film is this kind of non-moment, when Jerome is between bait-and-switching Laura and achieving any success with Claire, and he shows up to the girls’ house to discover that no one is actively waiting for him. Jerome had been relying on his sexual powers to sustain him through the summer without realizing that, like all power, it had been given to him by others, and came with certain responsibilities and rules. Minus their intrigue, he’s alone and a little pathetic. And you, watching in bed, with only your own knobby knees for company, can relate.

Still from Jordan Peele, Nope, 2022, 130 min. Courtesy: Monkeypaw Productions

Jordan Peele, Nope (2022)

Jordan Peele’s newest movie is a lot like Jaws: a summer blockbuster about hunting the big one, balanced on the fine line between horror and farce. The difference being that, while Spielberg’s concept was facile enough to invite interpretation, Peele’s is deterministically riddled with metaphor — mostly revolving around the ethics of image-making. Keke Palmer and Daniel Kaluuya play sibling horse-wranglers who are also descendants of the jockey in Eadweard Muybridge’s first photomontages. They battle an alien that looks a lot like a giant eyeball, and that feeds on terrestrial life by sucking it into its gaping, pupil-like maw. Your chances of saving yourself are higher if you don’t meet its gaze. Funny enough, our protagonists don’t want to kill the beast so much as document it — and their doing so involves resorting to some distinctly old-fashioned, Muybridgean techniques.

All this would be plenty for Peele’s cottage industry of YouTube explainers to unpack even if he hadn’t thrown in the weird side-plot about a berserk chimpanzee, which is so tangential to the main storyline that it actually requires some unpacking. Kaluuya and Palmer are so busy dancing around these signifiers that they hardly have time to introduce themselves as characters — though perhaps their reticence is intentional, since the film is also trying to be a revisionist Western.

I admire Peele’s ambition to deliver blockbusters with brain, and to do so at a time when the rest of Hollywood increasingly deserves violent polemical satire. But ever since the tectonic success of Get Out (2017), his productions seem overeager to deliver intellectual goods without satisfying basic requirements of substance and plot. It’s poignant, perhaps, that the alien from Nope feeds on and eventually suffers from a bad diet of simulacra, but throwing bones to critical theorists in the crowd doesn’t erase some of the film’s more fundamental issues, like: Why does a horse wrangler seem so indifferent to the fate of his horses?

Or maybe I just can’t solve that part of the puzzle myself. I recommend seeing this film in theaters, as a respite from an Adderall-aided binge-reading of Jean Baudrillard. If you don’t come up with a grand theory that encapsulates all of its references and Easter eggs, it’s my sincere belief that you should get your money back.

Still from Eric Rohmer, Claire’s Knee, 1970, 106 min. Courtesy: Les Films du Losange