“It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth,” Nietzsche once said, and the recently appointed curators of the Portikus in Frankfurt am Main would seem to agree. Liberty Adrien and Carina Bukuts first met in 2019 and, like many of us, they started going on communal walks at the height of the pandemic’s first wave. Strolling through Berlin’s Charlottenburg district, they discussed art criticism, feminism, and the future of exhibition-making, before deciding to work together and “gaining” their idea of worth — that art should be connected to the world at large.

In a sense, this was nothing new for them. Adrien is a self-proclaimed French autodidact, who had previously founded the independent exhibition space Âme Nue in Hamburg and collaborated with the French Ministry of Culture on art history research and exhibitions, and Bukuts is a German American, who had established PASSE-AVANT, an online magazine for contemporary art and discourse based in Frankfurt, before moving on to frieze. Bukuts emphasizes that Âme Nue and PASSE-AVANT are “city-based projects” dedicated to the cultural lives of their respective cities.

The first instantiation of their joint attempt to connect art to the world at large was the exhibition parcours “Balade Berlin,” which directed visitors through the same Charlottenburg streets that aligned their thinking. The exhibition showed works from eight artists based in Berlin, such as Slavs and Tatars, Jimmy Robert, Studio Pandan, and Ulrike Ottinger in public spaces like the Institut Français, the Charlottenburg townhall, the Orangerie of the Charlottenburg Schloss, or on advertising columns on Mommsenstrasse and Wielandstrasse. Works included posters and flags and ceramic pieces of bread as well as a bouquet of dried discarded palm leaves. “All of the artists were excited by the invitation,” Adrien explains, “since they rarely had opportunities to do something in the city they lived in, despite having shows all over the world.” At once global and local, this exhibition about the perceptions of the word neighborhood was situated in a particular context and worked with the location’s specificity.

The same can be said for Adrien and Bukuts’ first major curatorial project at the Portikus, located on a small island on the river Main and connected to both sides of Frankfurt by the Alte Brücke. Asad Raza’s Diversion (2022) channels this river through the exhibition space, allowing visitors to wade through the waters that typically remain an abstraction — unlike the Rhine in Basel, you would never swim in the Main, which mostly charters large barges with goods and tourists, and always remains “out there.” Visitors to Diversion are also met by Raza’s “custodians,” locals who provide information about the river and grant an opportunity to drink a highly filtered form of the highly polluted waters in the downstairs space beneath the gallery’s main floor. When drinking it, you implicitly undersign a contract of trust, and I for one suddenly felt — like, deeply felt — the violence that we humans commit to the world around us. The show is about our lost relationship to water and it’s an elegant and powerful exploration of its title, which is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the act or instance of diverting or straying from a course,” or “something that diverts or amuses; a pastime,” in that the water is literally re-coursed through the gallery and the piece provides a space to be playful and take off your shoes and come together — there’s something awkward and charming about splashing around barefoot with other unfamiliar visitors in something you both know is dirty. Should you be brave enough to drink the totally safe water, the custodians will even sing you a song for starters.

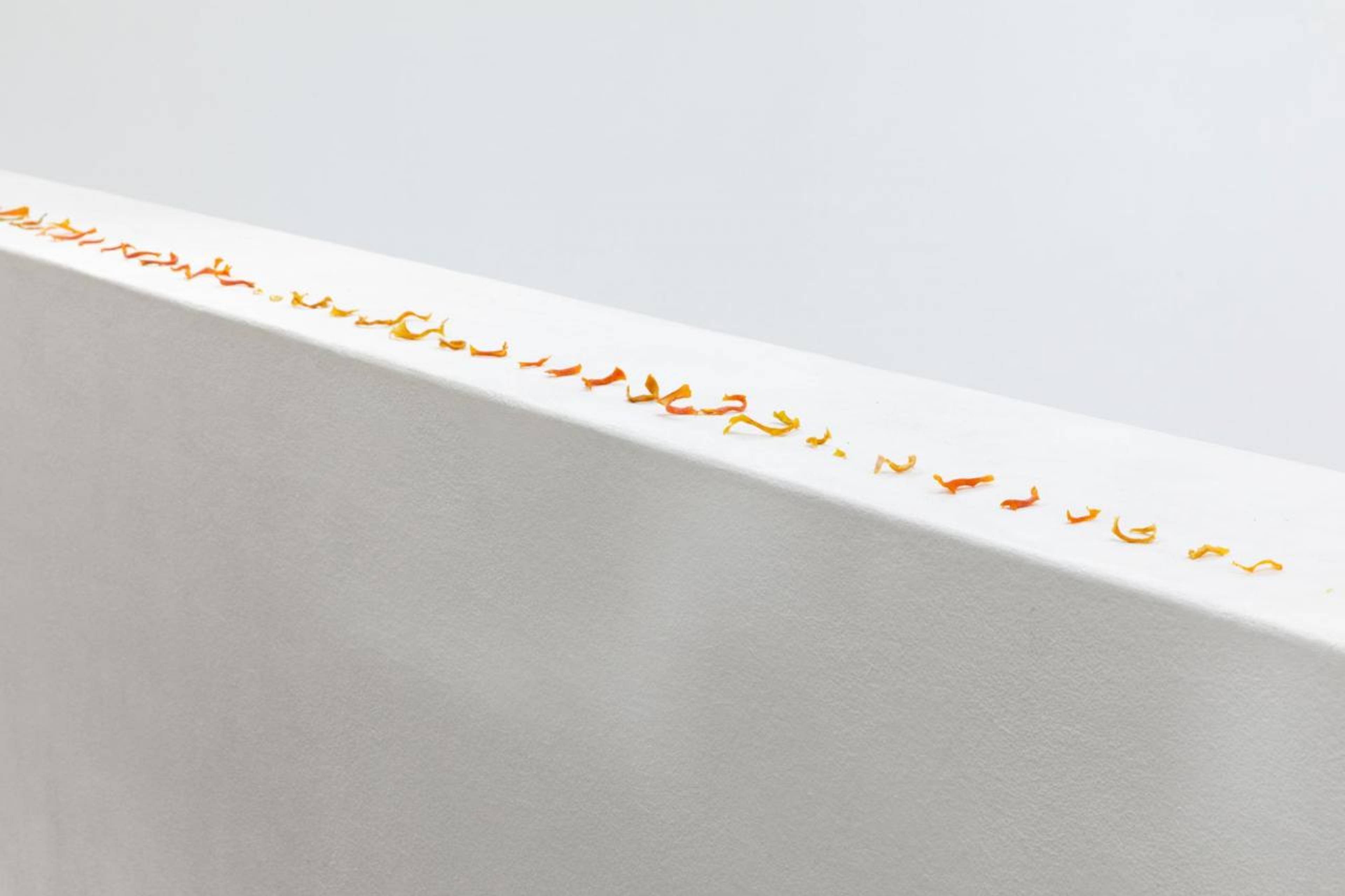

Raza’s exhibition also features an artist publication, a free newspaper edited by the artist and Mathew Hale and designed by Studio Pandan with texts and images by several writers and artists that can be taken home free of charge. This print diversion through Emily Dickinson’s poetry, a Tacita Dean contribution, horoscopes, crosswords, and a meditation expand upon the exhibition’s theme, and a German translation was inserted into the local edition of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on the day of the opening, which is another act of diverting: this time of the reader’s attention to the current exhibition. The curators suggest that the hope here is for Frankfurters to develop a deeper connection between the city, their daily lives, and the institution — “we want to come to you,” Adrien tells me as she indicates the plan for all future exhibitions to be featured in the newspaper. Bukuts doubles down on this and insists, “we don’t see ourselves as being on an island. We’re on a bridge and we want to build bridges into the city and into different communities.” This is why Raza’s practice is perfectly aligned with their curatorial raison d’être: by working with locals in the places he shows, Raza suggests that “you too can be a part of the institution,” as Bukuts puts it.

To further connect with people in Frankfurt, the curators intend to break up the three-month cycle of major openings with smaller events like listening parties. “We also plan to have copy machine residencies,” Adrien says, where artists will be invited to do a weekend-long residency and create a zine on the institution’s copy machine. The aim of these small events is to make Portikus a place where people can gather on a regular basis. But the real goal is even stronger than establishing some generic sense of community — Adrien emphasizes that “it’s about making new friends.”

Here, I’d like to divert to the second meaning of diversion, which is related to recreation. The curators of the Portikus (like those of documenta fifteen) don’t want the visitors to hover at a critical distance — which is a fiction in my opinion that piggybacks on Donna Haraway’s situated knowledges. They want the people to be involved in the exhibition and have fun. They want you to dip your feet into what they’re exploring. “In November, we’re opening a show with artist Ximena Garrido-Lecca and I think Raza and she share an interest in questions of relations,” Bukuts says, “Her projects often reflect on ancient knowledge, and address how natural recourses have been and continue to be exploited for capitalistic purposes.” Both Raza and Garrido-Lecca question what has been lost and why and when I ask whether this will be a general theme, they both look at one another with smiles that suggest ‘just how much are we willing to reveal?’ The curatorial program is “like a mixtape,” Adrien says. “There has to be contrast but there also has to be a continuity.” And it is their willingness to engage with contrasting forms of exhibition making (including, an artbook fair with an “architectural piece” by the Barcelona-based collective MAIO during the Frankfurt Book Fair) that connects them to Kasper König’s original intent for the Portikus — namely, that it should be a place for experimentation. Let’s see where this walk leads us.

“Diversion”

Portikus, Frankfurt am Main

25 Jun – 25 Sep 2022