“Life is a construction site,” Klaus Biesenbach duskily intones over a PA, his chattering audience gathered for the 20th-anniversary dinner of Gallery Weekend Berlin (GWB). Typical of curators, his aphorism rips the title of another work, the 1997 feature Das Leben ist eine Baustelle, a sweet nothing of a film about falling in love, despite jail time, job loss, and a possible HIV infection, in post-Mauerfall Berlin. Standing on the Neue Nationalgalerie terrace, our silvery emcee made light of the fact that the city’s next prestige art institution, the Museum of the 20th Century, is presently a cement canyon of tarpaulins, scaffolding, and rebar, while reminiscing on a more romantic moment in the capital’s history.

Colloquially, Baustelle also has a figurative meaning, more generically implying a locus of responsibility, a commitment to be worked through. In Berlin as in wider Germany, that site is the chasm that has opened up since 7 October between its public institutions and a substantial tranche of its arts-and-culture workforce. Emblematic of this rift, wheatpastes around the city appropriated GWB’s graphic identity with phrases likes of “MASS MURDER / MIXED MEDIA / DIMENSIONS VARIABLE / GENOCIDE WEEKEND BERLIN,” while, just hours before the exhibitions’ public openings, police arrested 161 protesters from Besetzung Gegen Besatzung (Occupy Against Occupation) in front of the German Parliament, uncomfortably suggestive of a sanitizing measure taken on behalf of a visiting jetset.

Whatever the flyer campaign and the violent eviction of the camp, the weekend’s festivities proceeded unperturbed, buoyed by a spate of sunshine that definitively dispelled the damp pall of winter. Moreover, Antonia Ruder, her first go-round as GWB’s new director complete, cheerfully confirmed to Spike via phone that most of the event’s fifty-five participating galleries were satisfied with both vistorship and sales volumes. But to mistake the seasonal turn in the weather and investment, under the sway of several alfresco spritzes, is, in its own way, to seek cover in a rosier past. Business as usual isn’t going to reverse the foundational fracture that, for all the rancor it has already engendered, will not be felt in its fullest consequence – most threateningly, in an exodus of artists from the city – for years to come.

Among the many colorful exhibitions that opened two weeks ago, four of the selections below encapsulate in as many forms – archives, sculptures, displays, and paintings – reckonings with the imprints of history. Probative, precise, and above all, soberly un-nostalgic, they might function as models for staying with history’s troubles, of tenaciously working on site; the fifth deserved inclusion for its exhilarating levity. All five remain open through at least early June.

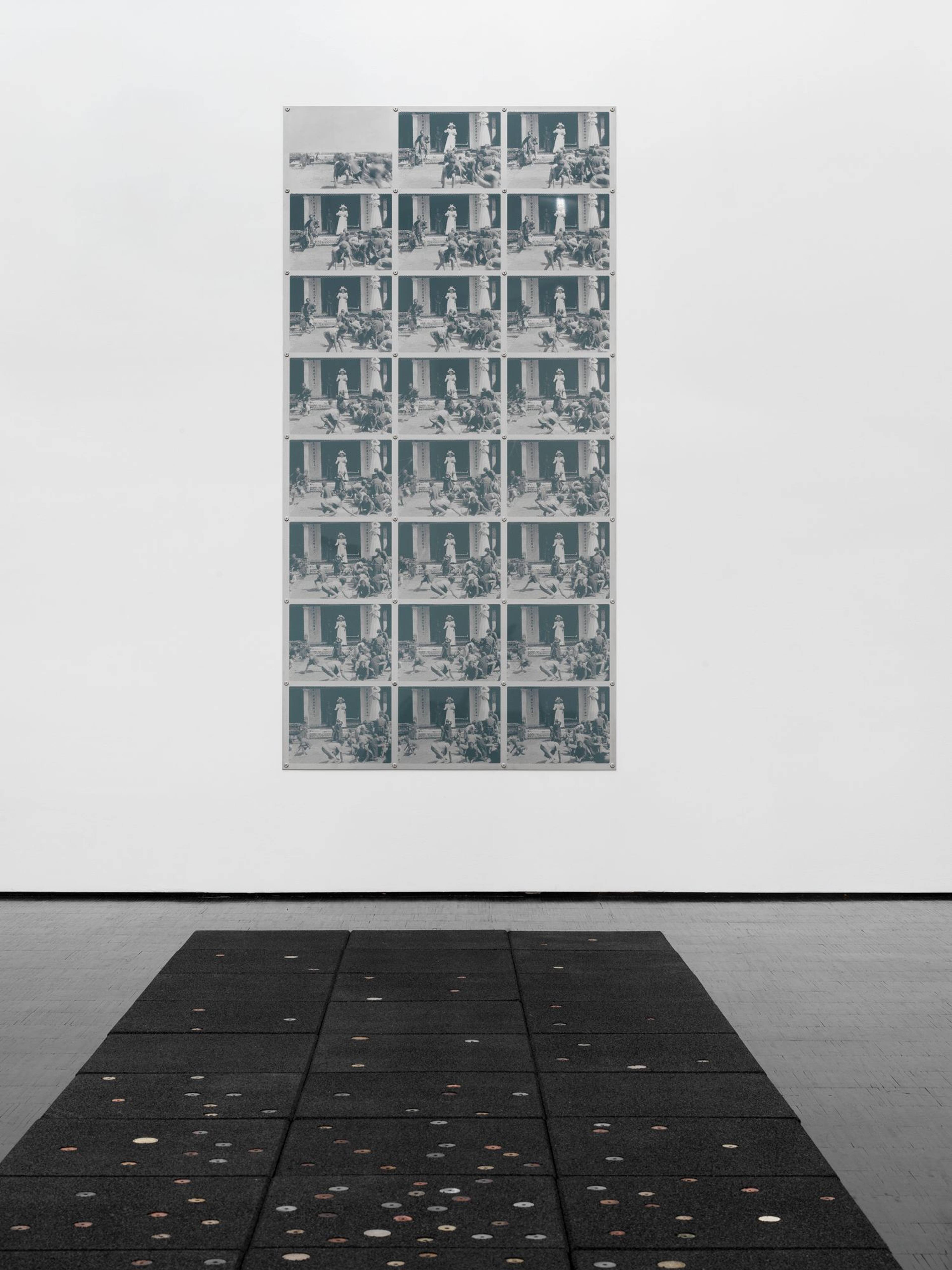

Views of Sung Tieu, “Perfect Standard,” Trautwein Herleth, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and Trautwein Herleth, Berlin. Photos: Jens Ziehe

Sung Tieu

“Perfect Standard”

Trautwein Herleth

27 Apr – 1 Jun 2024

“I realized very early on that I had a great interest in bureaucracy,” Sung Tieu (*1987, Hai Duong, Vietnam) said during a recent Spike artist talk. In her scrupulous study at Herleth Trautwein in the import of keeping track, a pair of lines run in parallel around the central gallery’s walls: One, a row of varnished measuring sticks, is bracketed into the plaster at chest level to form a thin lip; the other, sitting atop that shelf, comprises a series of shorter rulers, these burned in with tiny, serifed type. Physically uncomfortable to read, the texts enumerate demographic, fiscal, and other macroeconomic changes in French Indochina in the early 20th century, marked by a step change in the reach and profitability of that colonial project. Shortly before those records begin, the introduction of the metric system in 1897 both simplified agricultural assetization and, in a mischievous accounting gimmick, shrunk what counted as a unit of land; direct tax revenue rose 62.8% in the period 1913–25, partly as a consequence. Meanwhile, a third path along the gallery perimeter, a floor path of black rubber mats studded with bronze and zinc piastres, ends in a smaller, adjoining gallery, where two steel panels are silkscreened with still images from 1899 of Blanche Doumer, the wife of the colonial Governor-General, throwing coins to Annamese children. If the arrogance of her husband’s rationalization scheme get lost in the stupor of poring over spreadsheets, can lady Doumer’s gesture, whose gross racism is immediately legible in the 21st century, sharpen an archival critique of such “color-blind” forms of bureaucratization? The devil, as Sung makes clear, is in the littlest details.

Views of Cosima von Bonin, “The Faker,” Galerie Neu, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Neu, Berlin. Photo: Stefan Korte

Cosima von Bonin

“The Faker”

Galerie Neu

26 Apr – 6 Jul 2024

In our epoch of ocean acidification and immeasurable trash islands, what image could better hyperbolize depression than Mae Day Petite Version (all works 2024), a gray-tartan whale who, eyelids drooping and fins dangling from a listless rope swing, is poised to swill from a flask stamped “OY VEY?” Cosima von Bonin (*1962, Mombasa, Kenya), whose sculptures make liberal use of Daffy Duck, plush marine life, and other fauna silhouettes to distill more human and more-than-human malaises, ventures a bleaker caricature in We and They: two panels of off-white cannons poking out of jet-black velvet, flown over by tattered flags proclaiming their fortresses’ respective allegiances. Darker yet, the nameless, faceless Other has no topos, but can be laid down and fallen into anywhere – a Looney Tunes-style portable hole.

View of Iman Issa, “Photograph—(Un)Like (M)Any Other(s),” carlier | gebauer, Berlin, 2024

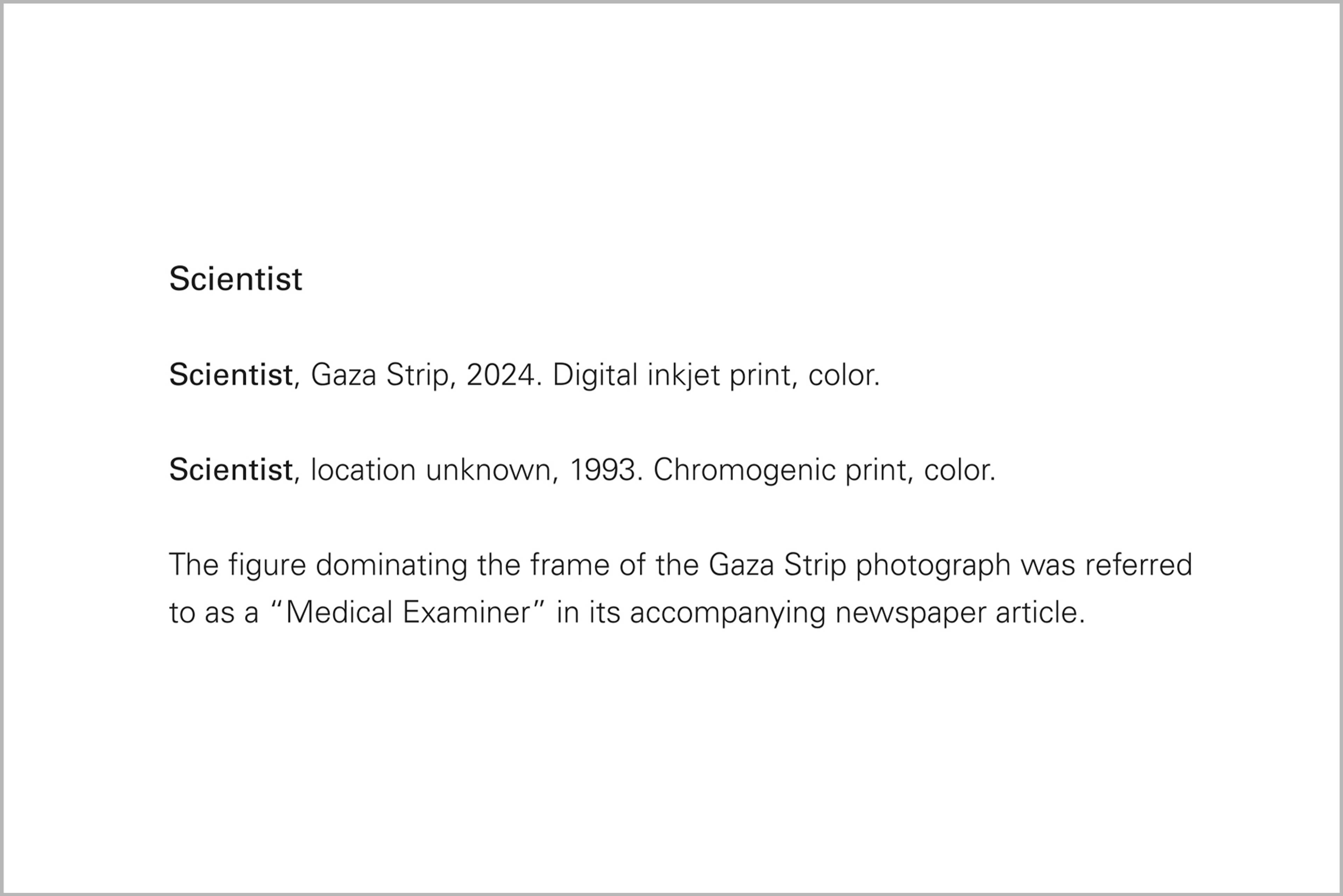

Wall text accompanying Iman Issa, Scientist, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin / Madrid. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Iman Issa

“Photograph—(Un)Like (M)Any Other(s)”

carlier | gebauer

26 Apr – 22 Jun 2024

To subsist in our contemporary image economy is to be willing to burn off its hyperinflated currency, several sheaves at a time. Iman Issa (*1979, Cairo) literalizes this reflex to glaze over milieu and person – if not to erase them outright – in a septet of new displays, each pairing a life-sized, lacquered-metal stick figure and a wall text citing its photographic referents. Sharing tuning-fork hands, eggish heads, and voids for faces, each spindly manikin is marked out by a single motif, like the attributes that iconize Christian saints. Scientist (all works 2024), featuring a beaker-y plexi sphere partly filled with azure silicone, derives from photo prints from the Gaza Strip (2024) and an unknown location (1993); Weaver, standing on cylinders of spooled thread for legs, from pictures in Giza (2024) and Montgomery/Harlem (1901). No less than the exhausted gaze, Issa’s parenthetical operator refuses the autonomy of any single photo. Either or. Yes and. Not at all.

View of Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, “Good Society,” Eden Eden, Berlin, 2024

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Good Society, 2024. Installation view, Eden Eden, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy: artists and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin. Photo: Graysc

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings

“Good Society”

Eden Eden

27 Apr – 30 Jun 2024

The ground-level frescos of Hannah Quinlan (*1991, Newcastle) and Rosie Hastings (*1991, London) star the modern turn of interwar Berlin in women’s style, the literal disposition of its public space, and, perhaps, their consonance a century hence. Hips cocked and knees soft, the cropped hair and bear calves in New Woman and Hier Ist’s Richtig! (It’s Right Here!, all works 2024) mark the twin franchise of wartime industrial conscription and Weimar-era suffrage. These women loiter on vast pavements, cut at right angles by smokestacks and hard shadows, proclaiming a new politics in the sheer fact of being outside – and, if you squint, to lesbians’ increasing cultural visibility. But if their Bubiköpfe (pageboy cuts), Spangenschuhe (clasp shoes), and Höschenkorseletts (pantie corselettes) distinguish that politics as conspicuously bourgeois, other of Quinlan and Hastings’s towering subjects further trouble the picture of progressive feminism. Near Public Order’s glowed-up Radio Tower, Berlin’s phallic landmark from 1926, one hand of a glowering, androgynous officer is twisted sinisterly backward, while, standing in a copse of poppies before a manicured lawn, the landly blonde in The Banality of Evil might come from the Auschwitz garden of The Zone of Interest (2023). Downstairs, the video Good Society follows a bald-pated, uniformed figure through their vaudevillean maquillage and onto a spotlit stage, before cutting to footage of Berlin’s armored police. Is it a paradox to work in drag and as a cop, or is identity even more manifold than intersectionality can generally accommodate? Maybe utopia isn’t a purity, but the sweaty work of holding together the contradictions.

Views of Mircea Cantor, “Thirst For Stillness,” Plan B, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy: the artist and Galeria Plan B, Cluj / Berlin. Photo: Trevor Good

Mircea Cantor

“Thirst for Stillness”

Galeria Plan B

26 Apr – 1 Jun 2024

Amid GWB’s relentless cascade of right now, is it gauche to install a work that’s fifteen years old? In Mircea Cantor’s (*1977, Oradea, Romania) Vertical Attempt (2009), a child seated next to a sink flashes onto a monitor and, grown-up scissors in kid hands, snips the water roping out of the tap. Nearby, a stream courses down a long copper gutter and swishes into a smooth marble ring, the sculpture Thirst for Stillness (2024) at once majestic and precariously out of proportion, like a long-legged wading bird. Upstairs, Archeology of Fate (2024) commemorates the shattering of a jug in Kandinsky-ish sweeps and jags of ink, its long curl of brown kraft paper hung like a score before an empty music stand. The video Fire Doina (2022), meanwhile, approaches a uniformed soldier playing a wooden flute on a leafy knoll. Otherwise unadorned, his breath fans a flame around the instrument’s foot that prevents his playing the last finger hole (and lowest note), as though the fire had taken the melody over from the musician. Equilibria of humor and omen, Cantor’s works emote the fountain as a spacious idiom, their circulations enduring even where they are reversed, merely implied, very literally cut.

___