I desperately want to love Las Vegas. I love the Las Vegas that Jean Baudrillard wrote about in the 1980s: a “hologram akin to the world of phantasy,” a “three-dimensional dream … held together by a thread of light”; but that is not the Las Vegas of the present. Nowadays, $10 blackjack tables are nigh-impossible to come by, and the slot machines, backlit screens bedecked by generic cartoon pirates, just feel like giant iPhones. The sports books, spectacular in the strongest sense with their walls of screens – as if Nam June Paik designed a streamer cave – are full of people looking at their phones, because that is where the real gambling happens. Casinos are some of the only establishments in the US where you can still smoke inside, which tells you something about their relationship to vice. There, you can hold a cigarette in one hand and your iPhone in the other, unclear which is doing more harm.

Driving through Sin City in his road-trip memoir, America (1986), Baudrillard wrote that “gambling itself is a desert form, inhuman, uncultured, initiatory, a challenge to the natural economy of value, a crazed activity on the fringes of exchange. But it too has a strict limit and stops abruptly; its boundaries are exact, its passion knows no confusion.” The limits of the desert are still intact (that is, until cloud-seeding weather modification drones turn Nevada into a rainforest), but the limits of the casino have eroded. Gambling, like emailing and watching pornography, has become just another thing to do on your phone while you wait in line for whatever. Las Vegas lost its sex appeal when it became the generalized condition of our miserable present. We have Las Vegas at home now, a boring dystopia dispersed with the rise of prediction markets.

My social media feeds have been replete, lately, with Clean Girl Aesthetic type content-creators explaining that app-based betting – long the province of men on the “Zynternet” – is for girls, too: “Turn $5 into $10 when u need coffee money,” one Instagram Reel posted by a twenty-three-year-old finfluencer advertised. “Make money while watching TV,” entreated another college-age woman in a Brandy Melville off-the-shoulder tee. These are the latest marketing push by Kalshi, a prediction market that launched in 2020 but really took off following a major funding round in October 2025, led by the venture-capital outfit (and prior victim of this column) a16z. Then there’s Polymarket, a crypto-native prediction market which skyrocketed into mainstream awareness when its traders accurately predicted Donald Trump’s victory, contra the polls, in the 2024 US presidential election. (Polymarket launched in 2020, existing in a regulatory gray zone that barred US-based users from placing bets until December 2025). Seemingly suddenly, prediction markets are now everywhere. Polymarket and Kalshi approached a combined trading volume of $40 billion USD in 2025. Dow Jones and CNBC have announced partnerships that link prediction-market odds directly to their business coverage, installing the means to gamble on the news directly into the news.

These belong to a wider and still expanding ecosystem of platforms advancing the Total Casinoification of Everything, alongside investment apps like Robinhood, sports-betting sites like DraftKings, and meme-stock trading. Generalizing the logic of speculation, they train users to relate to the future as a series of monetizable events, a constant stream of information compressed into probability and price. In effect, they democratize the right to write derivatives contracts on any manner of phenomena, this “speculation as a mode of production” turning what was once the province of the financial sector into the condition of all industries, and potentially, all social relations.

With the onset of prediction as a dominant cultural logic, we’re all market-makers and market-takers arbitraging the contingency of real events: life, death, love. It all feels pretty hopeless.

It is hard to imagine that the now-widespread ability to finance your daily caffeination by betting on, say, the outcome of an actual war – or even something as comparably inane as whether Taylor Swift will get knocked up before she marries Travis Kelce – could ever be construed as a social good. But advocates claim that prediction markets are better at truth-seeking than traditional channels like news, polls, and punditry. Precisely because they’re financially motivated, prediction markets are taken to be stronger channels of public opinion; they incentivize you not just to mouth off for attention, but to put your money where your mouth is.

This particular flavor of dystopia feels thoroughly contemporary, but prediction markets are not a new idea. In the early 2000s, the US Defense Department’s research and development agency, DARPA, proposed building a “policy analysis market” that would enable investors to bet on the likelihood of events like terrorist attacks and coups; the plan was cancelled the day after it was announced, on the basis that it was “ghoulish” (or at least “bad taste”) to bet on death. But the intellectual justification for such an idea can be traced back as far as the mid-20th century: in 1945, the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek argued in “The Use of Knowledge in Society” that markets are, in essence, information processors. The “marvel” was that, even as knowledge is dispersed throughout the social body, markets communicate condensed information via price signals. Prediction markets, it would follow, also aggregate expectations among individuals each acting with incomplete information, converging, by pricing users’ confidence in their predictions, on a more “truthful” outcome than a single actor could have foreseen. They wager that the sum of this knowledge can foretell the future. (What ever happened to auguring by looking at the night sky; to “Source? It was revealed to me in a dream”?!)

What Hayek’s fantasy of markets-as-information-processors failed to account for was that markets often fail in predictable ways. Price is a low-res information source, lossy and myopic; markets often send badly misleading signals about what is actually socially desirable. Condensing information from a complex world into a single quantitative index and hand-waving away externalities, price reveals only a selective kind of truth. A report on DARPA’s abandoned attempt to build a proto-prediction market acknowledges as much, noting that the idealization of efficient markets, “in vogue mainly in the 1970s” has, since then, “lost much of its luster.”

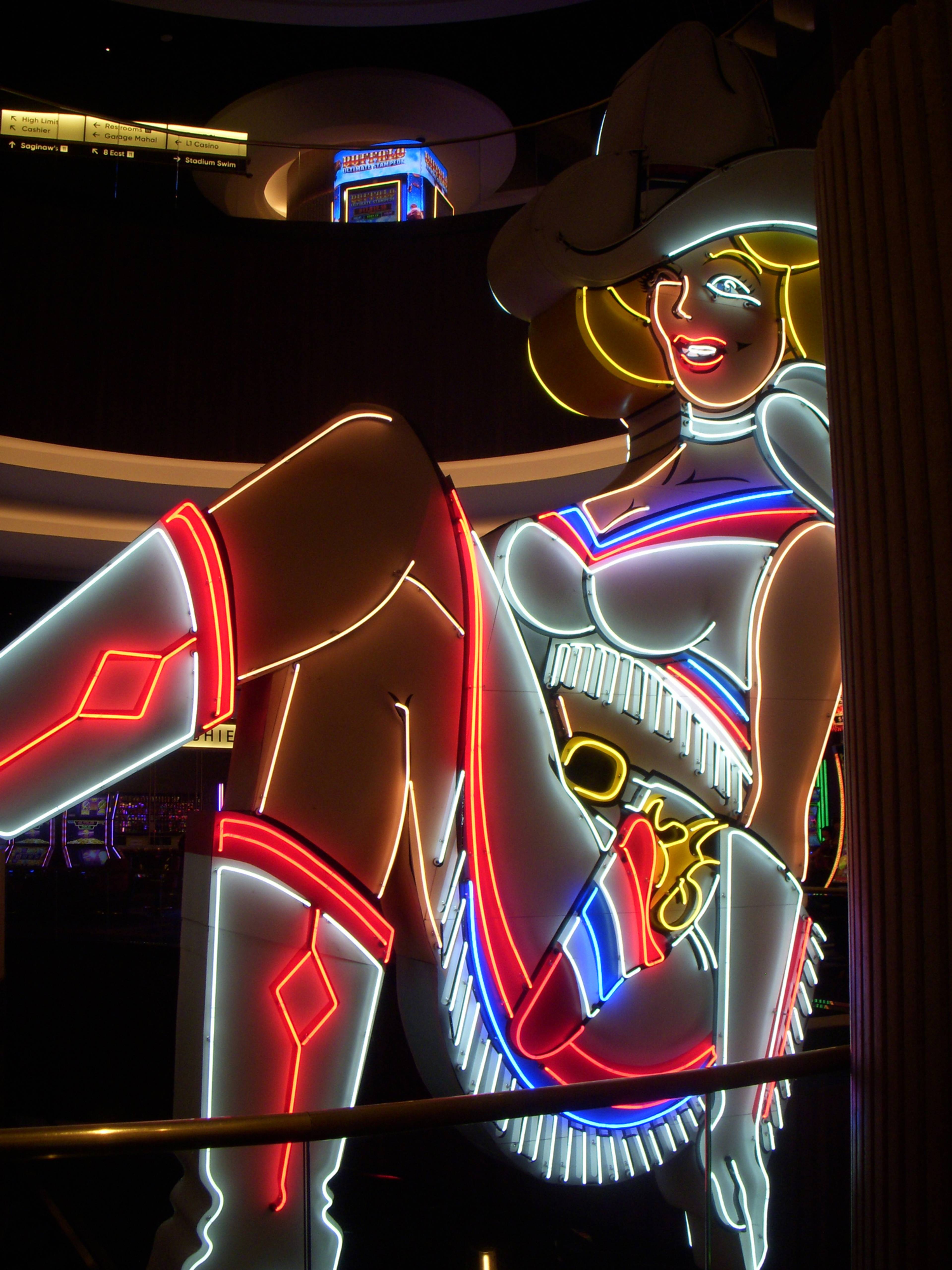

Why, then, does this hangover from Hayekian thought suddenly have so much power in the present? I would hazard that prediction markets are popular now, not because public belief in markets has been restored, but rather the opposite: because public belief is at an all-time low. Only against a backdrop of total Gen Z financial nihilism could gambling be dressed up as a legitimate form of investment, a power to the people, rather than the creep of casino volatility into everything. Yet, the casino metaphor also elides a key difference: unlike the Bellagio, Polymarket and Kalshi are peer-to-peer exchanges. You’re not playing against the house, but against each other – and against real people whose outcomes are rendered as abstract events. Still, despite their decentralization, they don’t disrupt extant power relations, not really. The house still always wins.

This “speculation as a mode of production” turns what was once the province of the financial sector into the condition of all industries, and potentially, all social relations.

For the platforms have to do more than keep the lights on: not yet profitable, they are bound to return on the strategic investment that props them up (Kalshi was valued at $11 billion in its December 2025 funding round; Polymarket, too, is pumped full of venture and angel bucks, including by Donald Trump Jr., who also happens to be a paid strategic advisor to Kalshi). Investments are not donations. This gamble on democratizing the means of gambling turns on cultivating addiction, insider trading, and even manipulation of real-world events as the feedback loops between wager and outcome continually tighten. And at the end of the day, these companies can always fall back on data monetization, in the classic style of platform extraction. This is a future that nobody wants, billing itself as “the wisdom of the crowd.”

The media theorist Jonathan Beller wrote, in his insanely prescient 2021 book The World Computer, that in the attention economy, “nearly every act or non-act becomes a signal, becomes information, becomes a pathway for M to M' (money to more money) for someone.” That someone is not – or at least not primarily – a sorority girl earning matcha money. With the onset of prediction as a dominant cultural logic, we’re all market-makers and market-takers arbitraging the contingency of real events: life, death, love. It all feels pretty hopeless. But it’s the hopelessness that, after all, keeps you logged on, furiously stacking your odds for the next bet, keyed into that “crazed activity” which is no longer, as in Baudrillard’s day, “on the fringes of exchange.” After all, in times without hope, what is there to do but hedge?