Grief is deranging. It is nonlinear, like modern warfare. Both have been front of mind lately, privately and indeed the world over. I gave up this column in December 2022 because I was losing my mother and felt like I was losing my mind. My mom studied Kabbalah, an esoteric Jewish tradition with a flair for numerology where counting, or keeping track, is imbued with divine power. I found some solace in the instructional tenor of religious ritual following her death. Praying for her nightly felt like executing a score for rules-based Conceptual art – a strange, durational performance that nobody signs up for, but is conscripted into, and carries out dutifully all the same.

I’ve been living in my hometown, which has transformed since I left a decade ago, maturing into a haven for tech startups and psychedelic therapy. Denver, Colorado is the skinniest city in America, and the gorpcore capital of the world. On the eve of my twenty-seventh birthday – Saturn return commencing? – I read my Spike piece on the death-defying tech-bro Bryan Johnson for a literary night at a local bar which is named after a neighborhood in Brooklyn despite being stuck in the middle of the country. Small talk has started to feel like a minor, unavoidable violence in view of all this ambiently circulating grief – mine, yours, overlapping and accreting. So many people, I have realized, dread answering to “How are you?” So instead, I’ve taken to asking, “What’s new?”

At the reading, I ran into a childhood acquaintance, and I asked her what’s new. Well, her brother (once a juvenile terror) is now a software engineer at Palantir Technologies, the dark and enigmatic “data integration” company headquartered here. Founded in the wake of 9/11 and named after the seeing stone from The Lord of the Rings, Palantir’s work is to synthesize data streams into actionable intel – making sense of the vast information we amass in our digital trails. They optimize the Wendy’s fast food supply chain, but also invent more efficient ways to surveil and annihilate people – the original “killer app.” Aggregating data to pre-empt crime (or so they claim), Palantir poses a massive threat to privacy. It is also currently trading as one of the most expensive large-cap stocks in financial history.

Advertisement for Palantir Technologies, Denver, US, 2025

My summer evenings have consisted of lazing around reading The Technological Republic (2025), a new, strange, and captivating book by the company’s co-founder and CEO, Alexander Karp. (The other founder was his law school roommate, Peter Thiel). Karp has a PhD in German philosophy, an odd background that shines through in his tirades against a tech industry lost in the sauce of consumer capitalism, too preoccupied with products like DoorDash and Klarna’s “buy now, pay later” burritos to notice “civilization level” problems and its own decline into irrelevance. I’m with him – until, that is, he contends that the solution is for Silicon Valley to turn its attention to defense tech, to beefing up borders and securing the future of Empire.

The almost-critical quality contained in the first half of his argument betrays that Karp is not your average American war hawk. The lore is that Karp did his PhD under the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, but this is apocryphal (although a good meme). His actual advisor was the psychoanalytic theorist Karola Brede, a member of the Freud Institute, from whence one might imagine Karp drawing his interest in the theory of the drives, especially the death one.

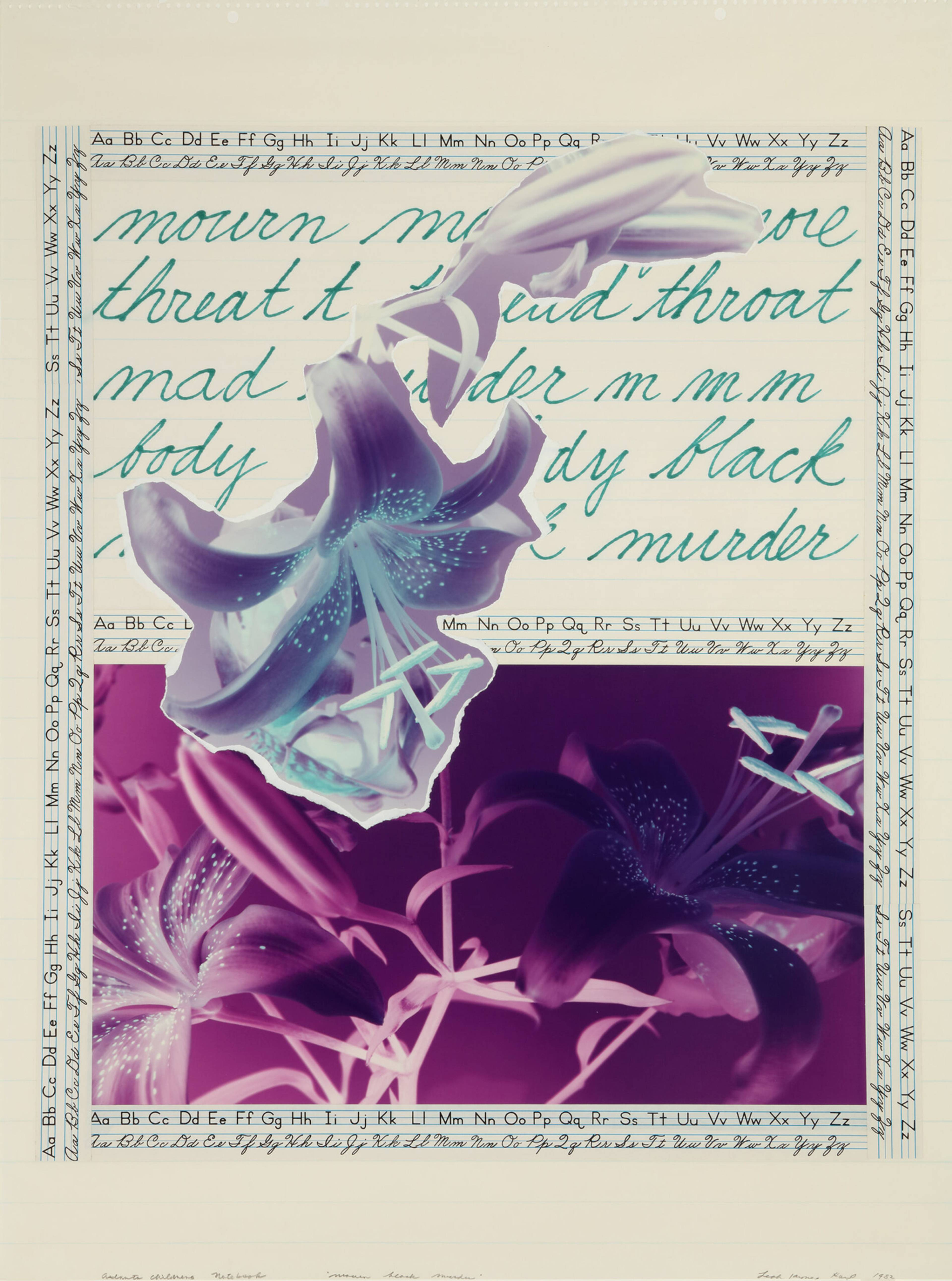

I share Karp’s flair for psychoanalytic theory; in no small part because I think a lot about mothers these days. Alex’s mother, Leah Jaynes Karp, was an artist, primarily working in collage – a medium beloved by the Italian Futurists, which preceded Palantir by a century as glorifiers of war. Her work was more critical of violence, though, with pieces like Mourn Black Murder (1982) touching on racial inequality (she identifies as African-American), questioning institutionalized killing machines and the flattening quality of statistics. As the artist Simon Denny has noted, they serve as an eerie, inverted mirror prefiguring the destruction-by-data advanced by Palantir’s all-seeing eye.

Leah Jaynes Karp, Mourn Black Murder, 1982, dye coupler print on paper with ink, 81.5 x 60.5 cm

Another piece of Karp lore caught my attention: Apparently, Alex is a student of Kabbalah. I heard he makes political donations in denominations of eighteen, the numerological equivalent of the Hebrew word for “life.” Palantir has perfected the opposite, elevating quantification to a matter of life and death.

Palantir has seen wild financial success since their stock went public, and the domestic defense-tech industry has surged alongside. It all betrays a certain bloodthirstiness – an open desire for violence perhaps repressed under the previous, liberalish order? This jingoism, and its fetishization of youth, power, and force, could have been cribbed straight from poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Founding and Manifesto of Futurism.” Proclaiming the launch of a new cultural vanguard in 1909, Marinetti wrote, in the French newspaper Le Figaro: “We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for.” (“And scorn for woman,” he continued.) Palantir’s billboards proclaim that they “build to dominate,” leading a tech-world contingent in an open affair with accelerationism drawn, paradoxically, from the past.

See also: In May, Andreessen Horowitz, one of Silicon Valley’s flagship venture capital firms, debuted a new brand identity. They ditched their unobtrusive sans-serif logo for a different look, more Gatsby-meets-Fountainhead in the Peloponnesian War of Robot Overlords, which is plausibly the prompt that someone fed Elon’s AI chatbot Grok to output this hokum. Their trend towards embracing the aesthetics and rhetoric of Futurism has been ongoing; Marc Andreessen, the firm’s principal, penned a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” back in 2023, which also reads like Marinetti fanfic.

Lazily recycling old visual idioms – also the modus operandi of generative AI – is no way out of the problems of the present.

Confusing past and future, perhaps deliberately, this neo-Futurism proclaims allegiance to the speedy, muscular, and new – but, in an obvious irony, it borrows its aesthetic idiom from a failed moment in 20th-century Modernism. The French philosopher Guillaume Faye termed gestures like these “Archeofuturism” in his 1998 book of that name, indicating that this impulse has been around for at least as long as I have been alive. Yet to question it is to be branded, somewhat paradoxically, a “decel” – a proponent of stagnation unto deathliness.

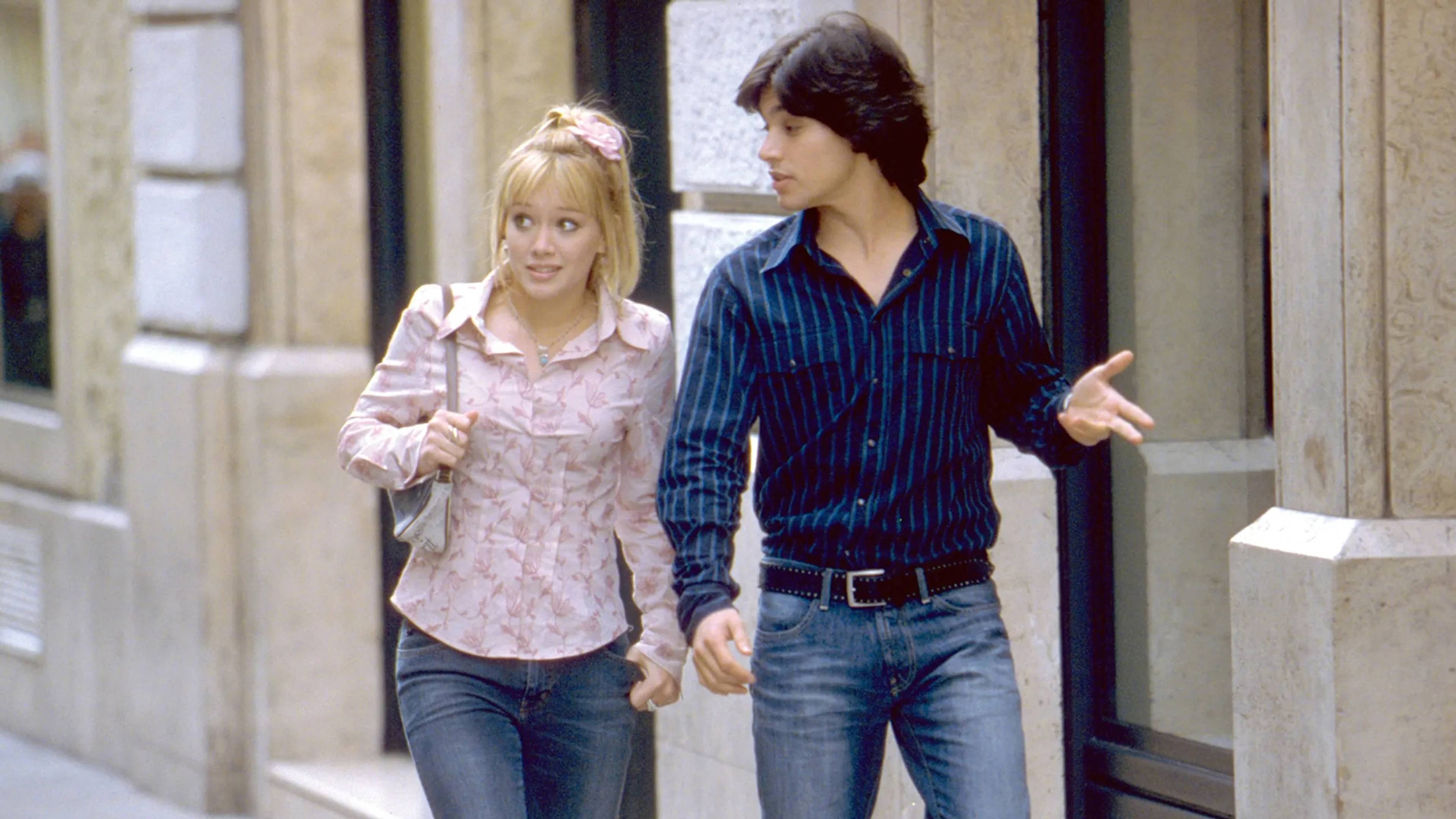

Whiplashed by all this empty accelerationism, a decel I may well be. But I’ll confess, I’m drawn to a different flavor of Italian-inflected nostalgia lately: repeatedly rewatching my comfort film, The Lizzie McGuire Movie (2003). Fifteen-year-old Hilary Duff’s Tiffany charm necklace – now that’s an aesthetic moment worth resurfacing. I’m vaguely aware that this yen for Y2K eurotrash was planted in my mind by an accelerating trend cycle, by past and present circulating in ever-tightening loops of looking at objects online. I watched the movie on my laptop, sitting on the terrazzo of the Rome airport’s Eataly, images and reproductions and commodities Duty Free perfuming the humid air on the eve of the Summer Solstice.

Still from The Lizzie McGuire Movie, 2023, 111 min.

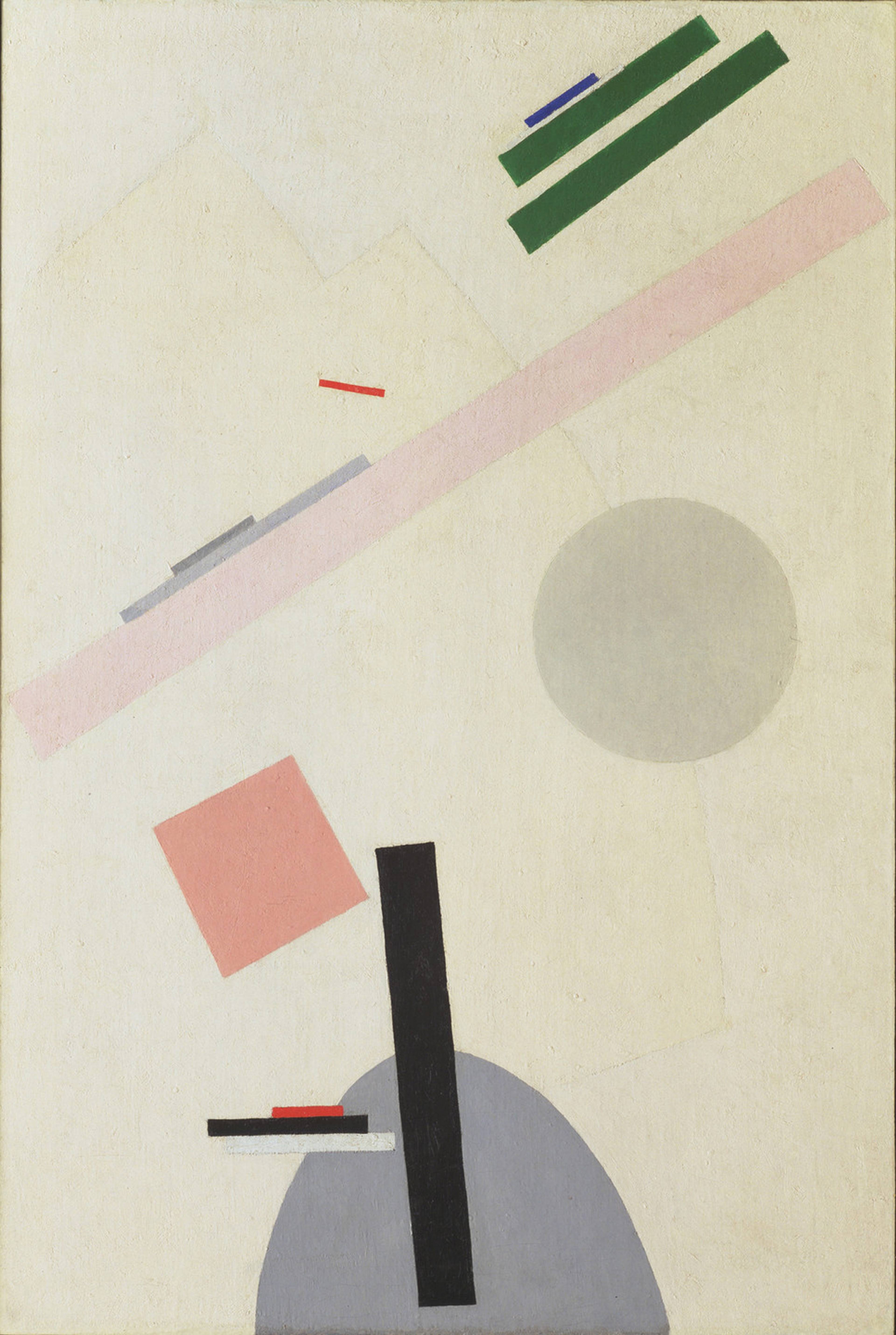

A fulcrum of the plot is that Lizzie’s kid brother sees a paparazzi pic of her on the streets of Rome, subject to a benevolent case of mistaken identity, exiting a gelato shop with an Italian teen idol. It reminded me that, a couple of weeks ago, Kanye West and Bianca Censori were papped – possibly back together – exiting a gelateria in Spain. In the much-retweeted photos, Censori is, characteristically, barely dressed, wearing her physique like couture. There’s something Futurist about her, too, in the sense that she’s built like a Kazimir Malevich painting. Like the Russian Cubo-Futurist artist’s deconstructed forms: a collection of shapes floating in space, all exaggerated curves and improbable angles, a posthuman assemblage. An architect by trade, Censori inhabits her body as a constructed dwelling; as artifice and edifice.

On the eve of the “Last Futurist” exhibition in Petrograd in 1915, Malevich declared that Suprematism – his title for the new avant-garde, eclipsing all that had come before – was poised to become “a new architecture,” stretching outward from the surface of the canvas into lived space. Is Censori, patron saint of beautiful bodily protrusions and demolisher of Ye’s Malibu beach house, an inheritor of that legacy? The utter absence of aesthetic innovation in Silicon Valley’s nod to the Futurists, on the other hand, reveals it for what it is: a dog whistle for rising tech fascism. It doesn’t posit anything. Lazily recycling old visual idioms – also the modus operandi of generative AI – is no way out of the problems of the present. Once again, I’m left wondering: literally, what is new?

Perhaps other questions cut closer to the heart of the matter. Like: What forces compel us to reach back to some romanticized past? I think grief is one such force. Loss collapses time. Effecting a confusion of past and future in the wish for what once was, it blinds us to the truly singular. At the outset of the Covid pandemic, Andreesen proclaimed that “it’s time to build,” calling (much like Karp) for the tech industry to cut through the complacency of a culture of banal comforts. Censori is famously given to demolition – taking a sledgehammer to history, a gesture that the Italian Futurists may well have celebrated. But “move fast and break things” (once the internal maxim of Facebook, whose founder has also gone fully MAGA) is a philosophy prone to producing collateral damage; just ask Kanye. Marinetti writes that “except in struggle, there is no more beauty.” Maybe that’s good news because there is struggle everywhere, surely more than enough to go around. Destruction can be transformative. But transformation is also, frequently, devastating. There is plenty to be learned from grief, and plenty to be grieved already, by anyone paying attention.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Painting, 1916–17, oil on canvas, 97.8 x 66.4 cm

Bianca Censori in Mallorca, 2025

___